OPENING

“What Does It Mean to Have Survived?”: Lyle Ashton Harris, in Conversation With Ryan McGinley

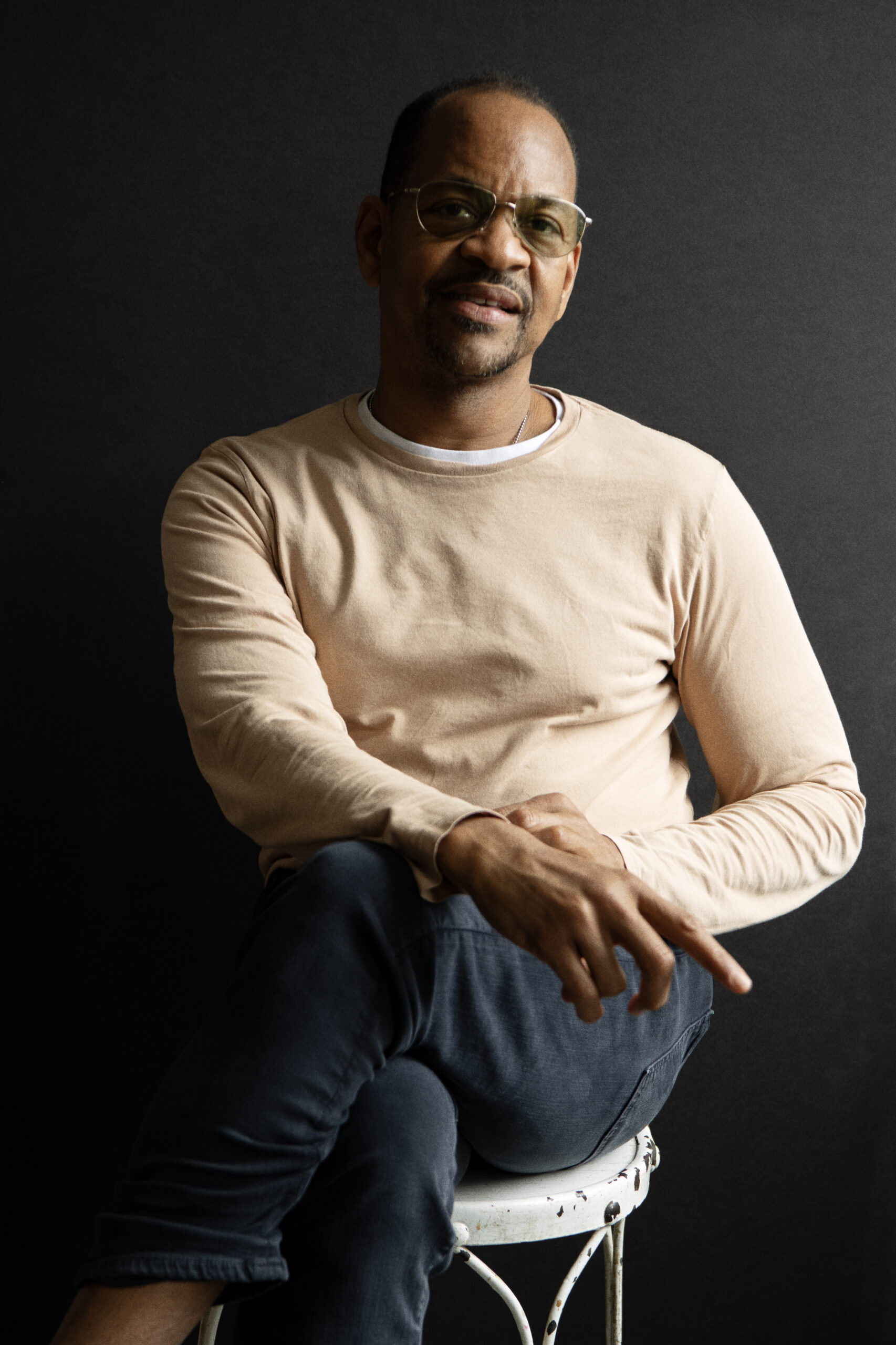

Our first and last love, a mid-career retrospective of the works of Lyle Ashton Harris, is anchored by twelve of the artist’s Shadow Works, which are large assemblages of ephemera, including print-dyed sublimation prints embedded in Ghanian funerary fabric. Each of the clusters were arranged thematically around notions of desire, gender, violence and family, which for the 59-year-old artist helped stave off a sense of boredom with his own creations. “My work has influenced younger generations and continues to, but how does it feel fresh to me?” he asked friend and fellow photographer Ryan McGinley shortly before the show’s opening. Calling in from his home upstate last week, Harris and McGinley had a deep, insightful conversation about art, activism, creative longevity, and their lesser-known self-care practices.

———

RYAN MCGINLEY: Hi, babe.

LYLE ASHTON HARRIS: Hey, where are you?

MCGINLEY: I’m in Chinatown at my studio. I have a little soundproof foam booth in here.

HARRIS: I love that.

MCGINLEY: I can’t hear the people working and they can’t hear me talking, so it’s perfect. What’s going on upstate? What’s growing in the garden in late April?

HARRIS: I planted in late fall after the first frost a hundred, maybe 125 or so bulbs of garlic.

MCGINLEY: Oh, wow.

HARRIS: So that’s coming up now. And a couple of weeks ago I planted a bunch of winter greens, bok choy and some salads.

MCGINLEY: How long have you been upstate for? I know you live up there half the time.

HARRIS: I started coming around 2015, but we used to do road trips up to the Catskills probably in the late nineties.

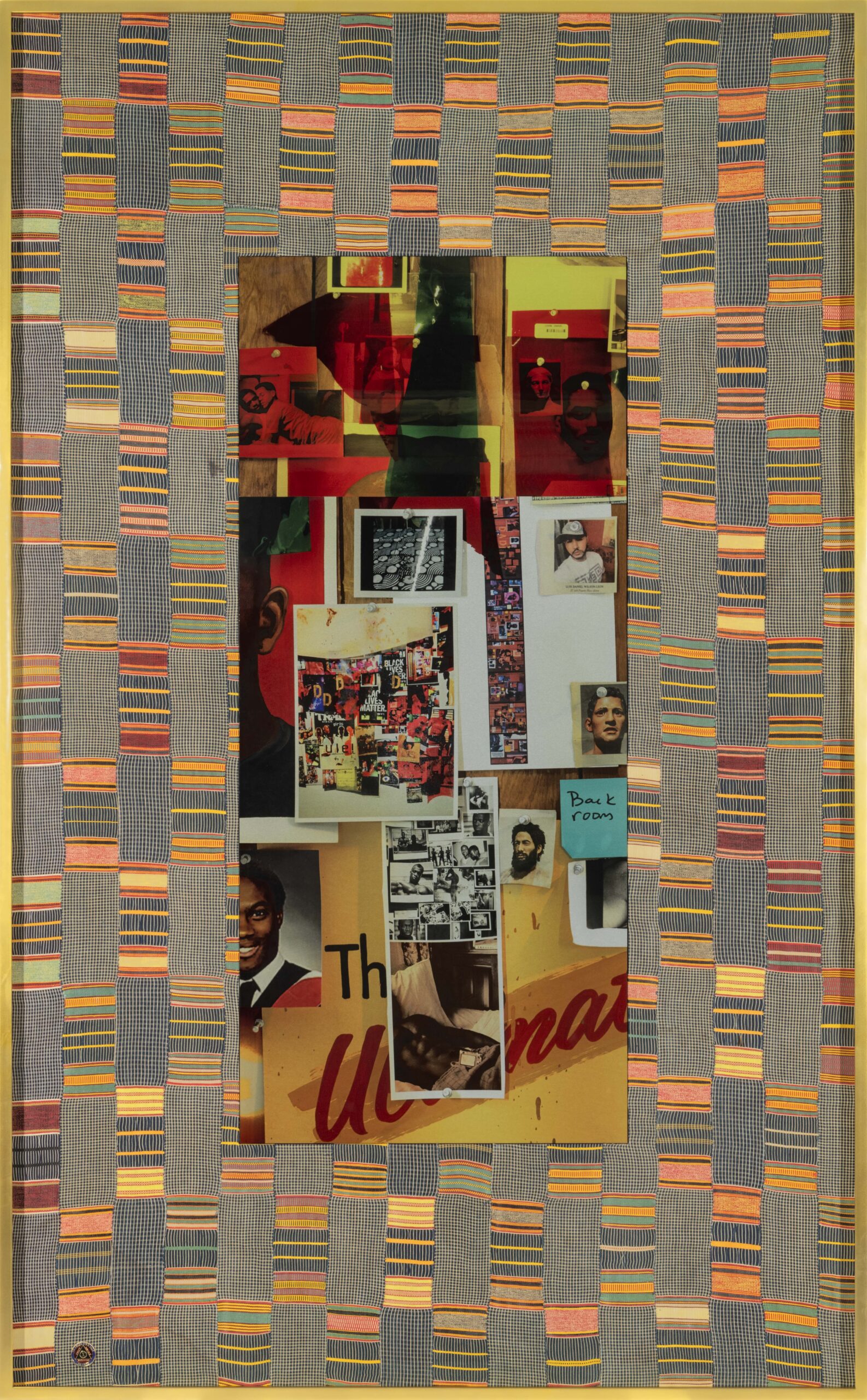

Oracle, 2020. Ghanaian cloth, dye sublimation prints, and artist’s ephemera 6’3.25”H x 3’10.75”W (framed). Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo.

MCGINLEY: Is there something upstate that you find inspiration in? I know that you’ve lived in New York City for a long time and of course you’ve lived in Ghana and Amsterdam and L.A.

HARRIS: I’ve done a lot of shooting in the landscape up here, like the Flash of the Spirit works from a few years ago. The relationship to the land has been important and I’m still exploring some things up here with regards to that.

MCGINLEY: How’s your dog, June?

HARRIS: She’s summer June. We went for a walk today, I had acupuncture and then we went to Olana.

MCGINLEY: What’s your favorite acupuncture point? Is it between the eyes on the wrist or on top of the dome?

HARRIS: I don’t know, sometimes the more painful, the better. Sometimes I like them between the eyes, and between the forehead is really good, or on the hand.

MCGINLEY: Something that people probably don’t know about you is that you’re really big into self care and that really inspires me. Can you talk about self-care as an artist?

HARRIS: Yeah. It’s a radical gesture, taking care of ourselves. It’s good to explore alternative health and modalities. I’ve been seeing an acupuncturist now for 30 years. A lot of people who are half our age now are doing Botox, so that’s sort of my Botox. So acupuncture is sort of my Botox, and also eating well. I love doing it in community with people, and cooking for people. It’s healing. It’s regenerative and it’s great for creativity, being able to share that.

MCGINLEY: I feel so privileged to come to your dinner parties because they’re amazing and your chicken soup is mind-blowing. I love being at your place upstate or at your apartment in Greenwich Village and seeing these salons that you curate. You bring people together and being a younger artist I really look up to you.

HARRIS: You do the same. I love coming to your place as well.

MCGINLEY: It’s very meaningful to see you do it, because you’re so seasoned. Let’s talk about you and your beautiful show coming up at the Queens Museum, Our first and last love.

HARRIS: You know how I came across that title, right?

MCGINLEY: How?

HARRIS: I was visiting my ex, a dear friend of mine, Tommy Gear, who formed a punk band in the late 1970s called The Screamers. We were in Seattle at Pike Place market and we had Chinese food, and that was my fortune. The original fortune that I got is in a journal that’s going to be part of one of the vitrines in the show. That’s the part I’m really excited about, all these memorabilia besides the more formal stuff. They have these journals and photographs and postcards from clubs that are non-existent.

MCGINLEY: I love watching you journal. Whether we’re on a beach or in a church or at your house, it’s a pleasure for me to watch you do it. Can you talk about your journaling practice?

HARRIS: I just find it very grounding. You’ll see in the exhibition catalog, there’s an appendix of all the images in the show, and it comes out of this class I had taken during the pandemic in this room. It was a one-year course called “Right to the Pandemic.” We went through all of BLM, the social protests in the city, but writing every Thursday from one to four. It was an opportunity to go deeper into some ideas beyond the journal. There’s an entry about this guy Marty that I met at SPEW-Two in L.A. in 1992. So it’s writing about the memory of those images. I like how the journals actually account for that in a way.

MCGINLEY: Yeah, absolutely. I always think of you as the living godfather of gender, race and sexuality. I think about some of those early works that you made and I feel like everyone in my generation or the generation below me is doing that now. I look at your works from 1989, the self-portrait you made of Michael Stewart where you’re in the police uniform in full makeup. This is the murder of an artist who was really close friends with Jean-Michel Basquiat.

HARRIS: Yes, of course. In fact, after Michael Stewart was killed, I remember Basquiat went to West Africa. He got deeply frightened about the possibility of being murdered.

MCGINLEY: Yeah.. You’ve been doing this for almost 40 years. It’s remarkable.

HARRIS: I started young.

MCGINLEY: I’m thinking about some of your provocative pieces, like the portrait of you and your brother gently kissing and you’re holding a gun to his heart and nude. That photograph spoke to me in such a way that it’s burned into my visual Rolodex. And to think about that being at the Queens Museum and thinking that it was made…

HARRIS: 1994. It’s wild, right?

MCGINLEY: Yeah. Like 30 years ago. How does it feel to have a retrospective happening in New York?

HARRIS: When the two curators initially reached out to me, I was a little concerned about doing a survey exhibition, but my good friend Chris Lew suggested that we do something thematic. I really love what co-curators Caitlin Julia Rubin and Lauren Haynes did, anchoring the show around works from my recent Shadow Works series, these unique assemblages, which themselves are dye sublimation prints that are embedded in Ghanaian funerary fabric. They’re quite large, and the show is anchored by twelve of them. They clustered the other works around them to explore recurrent themes such as sexuality, gender and violence. I like that it gives viewers (and myself) a way to think about the work in a fresh way. So to see clusters around the idea of desire or family—what does it mean to then bring in pop culture? Thinking about Interview or other magazines that have influenced me with, say, high art. I like that play. For me, it teases at what I consider to be the real or experiential. That’s what feels fresh about it. The show does have some of those earlier works, which I was honestly ambivalent toward, or more like, “Do we have to show those again?” I remember I was seeing this guy when I was on Fire Island last summer, and he opened one of my books, pointing to my triptych Americas to and says, “This is everything!” So you’re right that my work has influenced younger generations and continues to, but how does it feel fresh to me? It’s important that the show could be interesting to me so I could actually enjoy it.

MCGINLEY: Lyle, the kids love you, you’re punk rock. People probably don’t know, but Lyle dresses very preppy and if you saw him–

HARRIS: Do I dress preppy?

MCGINLEY: Yes, and we love that. I remember hearing a quote that you said from back in the day. You were like, “I was a sissy by five, a faggot by seven, a bitch by 12, and a cunt.” And I was just like, “I love this person. I want to know this artist.” You’re so major. And you’re in the Collection of MET, the MoMA, the Guggenheim, the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Tate Modern, MOCA LA, Getty Museum and more. Period. As a younger artist, it’s very exciting to have you as a friend and to be able to do stuff like this.

HARRIS: Speaking of youth, did you go to Printed Matter’s New York art book fair this past weekend?

MCGINLEY: I didn’t.

HARRIS: It was like, “Oh my God, the kids are alright.” It was so combustive and the energy was so democratic. Books are back with a vengeance. I love books! I love the idea of the fact that they’re deeply intimate. The whole process of making a book is different when you do research online. It’s a very different thing, having that object and thinking about placement and choice. That’s why I always love coming to your studio and seeing the whole process of laying it out, it’s so rich.

MCGINLEY: I love that you brought all your students from NYU over.

HARRIS: They loved you.

MCGINLEY: Can you talk a little bit about being a teacher and what that has brought to your life?

HARRIS: I’ve been at NYU for a number of years and it’s always a surprise. You never know what you’re going to get, but the students are super fresh and they keep me fresh and they don’t really care who I am. Really, it is about that connection. I’m always surprised by the warmth and the charge I get when someone gets something, when they work through a series of creative exercises, having them push through despite resistance. It’s work, but it’s something that I find deeply enriching. It’s wild because my students, this last class, half of them are missing. A couple of them have been arrested. These recent protests are like occupations. It’s inspiring. Growing up in the family that I did, it was very political, and you would hear about death, you would hear about people who were comrades of my father who had been killed. I went through my own way of engaging with that material. My activism was more about doing it through artwork. It is interesting that these young kids right now are putting their bodies on the line.

MCGINLEY: Yeah, these are very challenging times. I know that you lived in Ghana from 2005 to 2012, and that they just passed some pretty heavy anti-gay legislation.

HARRIS: Yeah, the Ghanaian Parliament did. But one positive thing is that the president has not signed it yet and most likely he will not, but it’s still scary that it got to this point. I was recently in Venice for the biennale vernissage and took part in Deb Willis’s legendary Black Portraiture(s) conference. I was so nervous about what I was going to talk about, but with some encouragement, I kept it very real. I thought, “How can we talk about shifting paradigms and not talk about gay asylum?” I cried and I spoke from a very personal place, having lived in Africa as a child and having a South African stepfather. A lot of young people came up to me afterwards and said, “Thank you so much for representing us.” To your point, young people need a voice. It’s not just about a photograph, but more of what it means to actually be able to say, “This is how I’m impacted by something.”

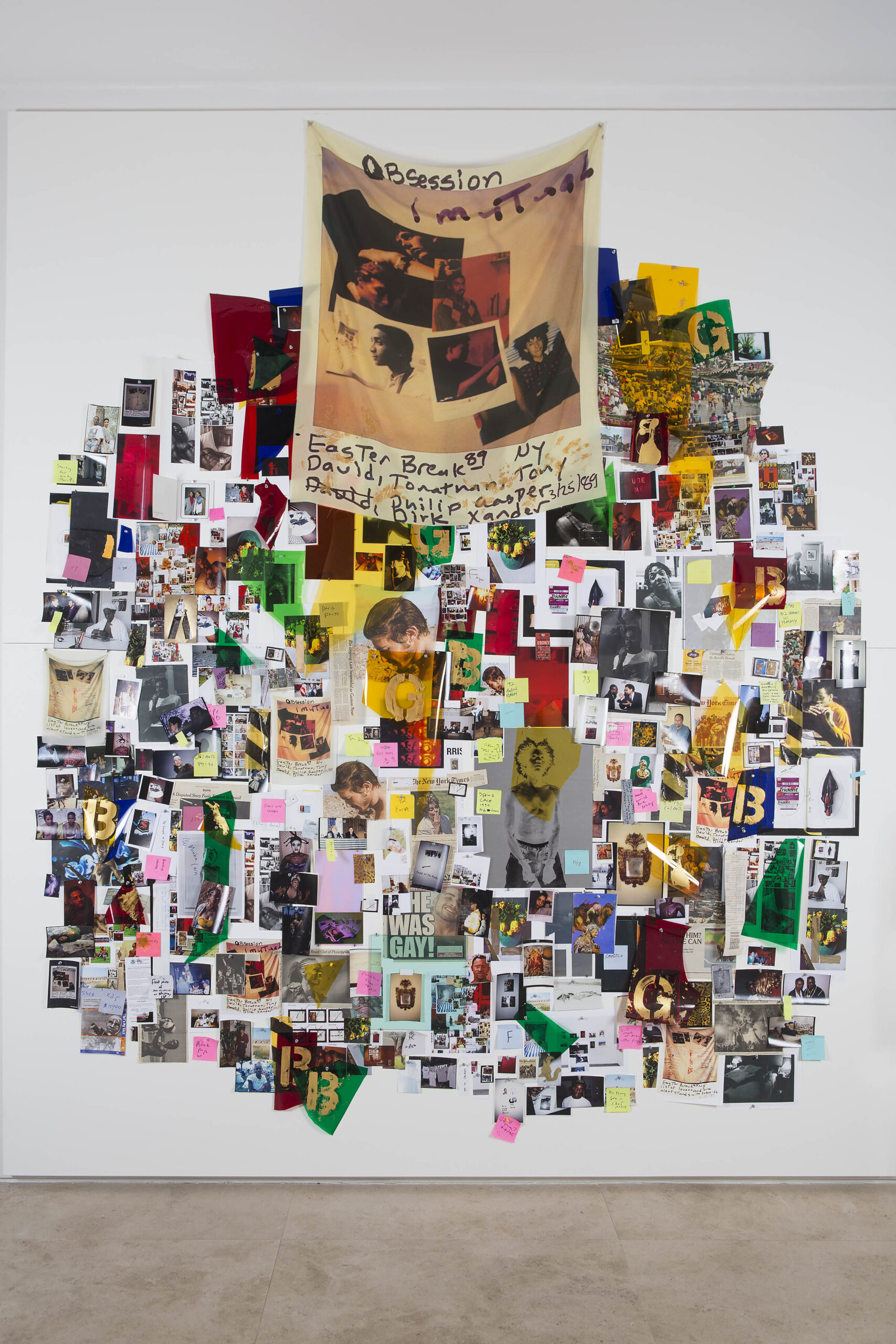

Obsessão II, 2017. Mixed media collage on panel. 11’ 1.5”H x 9’8”W. Courtesy of the artist.

MCGINLEY: Definitely.

HARRIS: You’ve been doing trans rights stuff and radical embodiment. I’ve also been deeply inspired by you and your generation and the work of holding a space where one could be in the world in terms of taking care of oneself and being able to have a voice and to hold space at the same time. These are new models. Even thinking about the way Warhol was initially rejected by the powers that be, or the art world, or fellow gay men, and how he radically created other landscapes, other spheres that were obviously artistic as well as political. In a way, it’ll be interesting to look at the children or the grandchildren of Warhol, because there is a different model that’s happening right now.

MCGINLEY: I was on the cover of New York Magazine and it said, “Warhol’s grandchildren in 2005.”

HARRIS: I remember that, yeah.

MCGINLEY: Also, congratulations on 20 years sober.

HARRIS: Oh, thank you.

MCGINLEY: That’s something that brings us together. Being an artist is a wild ride, and it’s good to have examples of people that are off the sauce and that do it. Creativity doesn’t die when that happens.

HARRIS: I thought it would, though. I’m thinking about when I made photography for the Brotherhood, Crossroads and Etc, or The Watering Hole and I don’t regret any of that stuff. It’s about learning how to have a space in which I can accept all of those things and at the same time, not to repeat them. It’s also inspiring and humbling to see a lot of young kids who are struggling. When we were recently in Palm Beach, they had that show of your work. And obviously I’ve experienced a lot of your work from the Whitney and I have several books, but this was from before. To travel back down memory lane, how was that for you? Those were early works and it was intense. There were things so radical about that type of embodiment and youth and vigor. But similar to you, with Our first and last love, there could have been a curator who would’ve gone through my archive. It’s complicated because in a way, it could have been easier with an old artist. But the fact is that the curator has got to deal with the embodiment. They got to deal with, oh, the artist is alive and the artist is present in the flesh, not only in the work. But there’s also some melancholia around that, or what does it mean to have survived? Because some of your friends and my friends have gone on and we know now there’s a renewed interest, particularly after the pandemic and AIDS activism. If you think about the suite of shows that were at David Zwirner, they had five shows on AIDS with Marlon Riggs, the great filmmaker and–

Brotherhood, Crossroads and Etcetera #2 [in collaboration with Thomas Allen Harris], 1994. Polaroid 2’H x 1’8”W (sheet). 2’11.5”H x 2’2.5”W x 2.5”D (framed).

HARRIS: Yes.

MCGINLEY: There’s a powerful photo [from your Ektachrome Archive] with Derek Jarman Caravaggio poster behind you. It says everything to me.