ANDY

“Warhol Wanted to Be a Girl”: Klaus Biesenbach, in Conversation With Wayne Koestenbaum

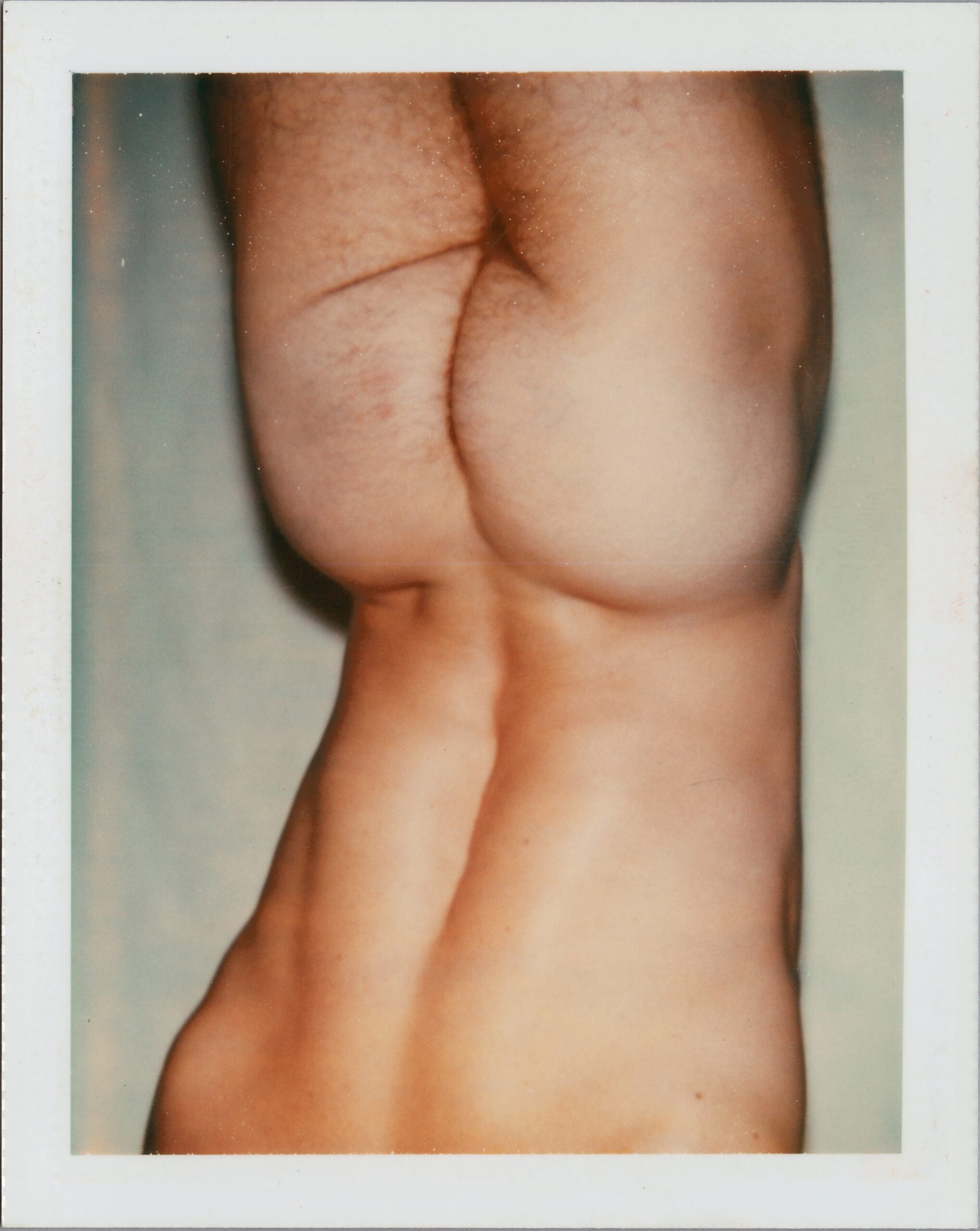

Self-Portrait in Drag (1980), Polaroid. © 2024 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Last month, a diverse and expansive new exhibition called Andy Warhol: Velvet Rage and Beauty opened at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. Curated by Klaus Biesenbach, the show homes in on Warhol’s lifelong exploration of beauty, particularly male beauty, which took on strange, provocative, and varied forms throughout the artist’s ouvré. For the exhibition catalog, Biesenbach held engrossing conversations about the show with a slew of Warhol enthusiasts, including Blake Gopkin, Donna de Salvo, Jessica Beck, and Wayne Koestenbaum, the author of a rich biography of Warhol published in 2001. Below, we publish Biesenbach and Koestenbaum’s conversation in full.

———

KLAUS BIESENBACH: I did a show that many people didn’t like. It was “Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures,” at MoMA on 53rd Street. It was quite a big exhibition on the sixth floor, where we projected the Screen Tests.

WAYNE KOESTENBAUM: Why didn’t people like it?

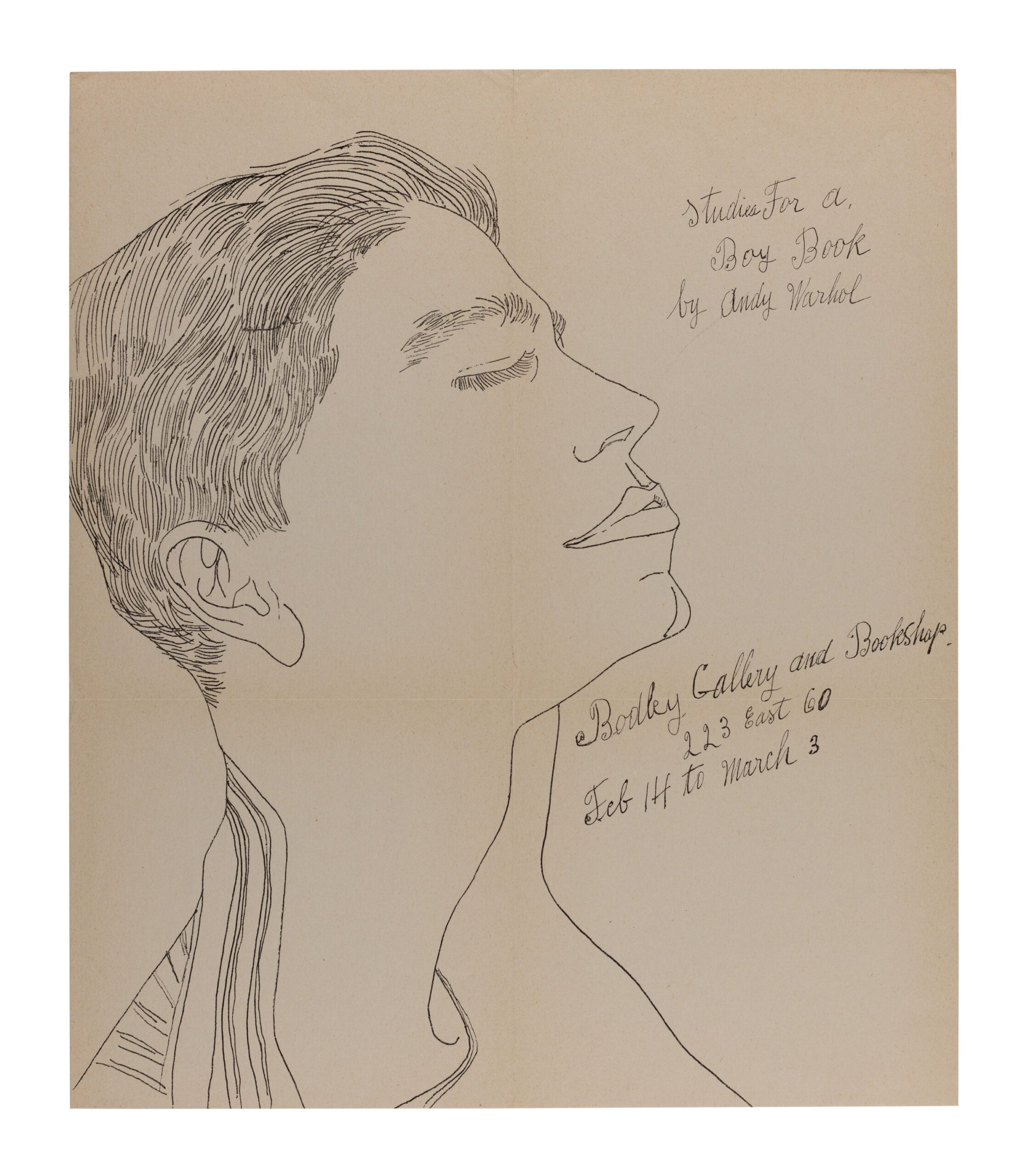

BIESENBACH: Because they thought the Screen Tests were film and we projected them as video. We showed Susan Sontag, Lou Reed, Blow Job—all those. They were big projections, the size of big paintings, and they were framed. It was quite a popular show. I started looking into Couch, Blow Job, the Polaroids, and for a while I was obsessed with the movie Querelle, which Warhol did the poster for, as you know. I always had the kernel of an idea for this upcoming show we are talking about. I actually wanted to organize an exhibition about fluidity, but with just one artist: Drella. The Warhol that was both Cinderella and Dracula. That was kind of how my thought process started. So it’s the sensual Warhol, the vulnerable Warhol, the queer Warhol, the explicit Warhol, the hidden Warhol, the closeted Warhol, and the proud Warhol.

Male Nude (1957), gold leaf and ink on colored graphic art paper. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

KOESTENBAUM: Has there been an exhibit that approximated your wish? I probably only know the shows that appeared in New York.

BIESENBACH: Of course there was the notorious Torso painting exhibition at Ace Gallery, 1977, but I feel it was underappreciated and underpublicized.

KOESTENBAUM: The thing that immediately came to mind when you texted me were the Polaroids that I saw at the Warhol Foundation. When I was researching my Warhol biography, I spent an afternoon there with a huge stack of Polaroids—all the sexy photos of Victor Hugo. Those images made a huge impression on me. They were the most explicit Warhol material I’d seen, and they were glorious and provocative and conceptually “out there.” As far as the hidden Warhol goes, there are films not often seen—perhaps nowadays they’re shown more?—like Couch, Blue Movie, Lonesome Cowboys, San Diego Surf. And I still find Haircut (No. 1) entrancingly erotic. Some parts of Sleep are also very erotic. When the camera pans down on John Giorno’s body—I don’t know if the camera itself is actually moving, but I recall a sense, in some scenes—

BIESENBACH: That you’re sinking in.

Double Elvis (1963), silk-screen ink and aluminum, paint on canvas. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

KOESTENBAUM: Yeah, you’re really getting down there. The film recreates the experience of dwelling very, very slowly with dreamboat John Giorno. And I remember thinking that this film’s putative boredom is overwhelmed by its eroticism—and mingled with it, to create a strange boredom-eroticism cocktail, characteristic of Warhol’s films, a sexuality founded on a supposed tedium. Even in the experience of looking through the Polaroids, I felt that sense of inundation, catalyzing a certain anesthesia, a consequence of overstimulated surfeit. It’s different from the inundation of, say, visiting the Kinsey Institute archives, or looking through a porn repository, where one can be overwhelmed by emotional deadness. Paradoxically, Warhol alleviates the anesthesia he also produces.

BIESENBACH: What is the relation of Warhol’s work and Mapplethorpe’s? If you see some of the Polaroids of Victor Hugo, there’s a Mapplethorpe quality to them; the Torso paintings, too. But perhaps they were just both working on the same taboo?

KOESTENBAUM: This is kind of an obvious point I’m making—but it strikes me that the temporal issues in Mapplethorpe’s work are housed within a photograph’s sculptural stillness, whereas Warhol’s photographs have a kinship relation to an arrested ongoingness, the durational flux we find in his films and his artistic process. Warhol’s films (and paintings, and everything else he made) imply a diaristic camera that’s always on, recording, so he lets us see and know that a photograph is merely part of a stream—not of actual time, but of a duration that artistic mediation has turned into a tangible, complicated fabric.

BIESENBACH: Of a before and an after. It’s always before and after, whereas Mapplethorpe is not about before and after.

KOESTENBAUM: Like in Ethel Scull 36 Times, or Jackie, we feel time unfolding and time suspended. So the composition of a Warhol photograph might not be arranged and sculpted in a conventional way, even if his compositions are as good as Mapplethorpe’s—better, really. Warhol’s are as stylized as Mapplethorpe’s. The two artists share, as fellow window-dressers, a George Platt Lynes aesthetic. But Warhol belongs more to the Pictures Generation, or to more cerebral strands of conceptual photography. Mapplethorpe isn’t quite in that weird echelon of the imaginary and the postulated.

BIESENBACH: Did Warhol have any strong women role models in his orbit? When you think about Jack Smith, and Mapplethorpe, and all these artists that have a strong relation to his work—there really aren’t any women.

KOESTENBAUM: His mother. His mother and, I presume, maybe fellow students at Carnegie. He had girlfriends, friends who were women, who taught him things. And Fassbinder teaches us so much about Warhol. Fassbinder replays the same themes as Warhol but in a Douglas Sirk register, at least in some of his films. So it’s impossible for me to think of Warhol and his women without thinking of Fassbinder and his women. Fassbinder’s and Warhol’s films echo each other, across the gulf of time, and that’s why Querelle—their point of actual intersection—is central.

BIESENBACH: But Fassbinder was the guy, and Warhol was a girl, in a way?

KOESTENBAUM: I agree that it’s fun, though strange, to call Warhol a “girl.” Is his supposed passivity a girlish behavior? Probably not. In his authorial signature and in his silence as a watcher—somebody who performed as a judge, a conscience, a scribe— Warhol wasn’t passive. He became, even in his silence and apparent non-forcefulness, a powerful and dominating directorial presence.

BIESENBACH: Lynda Benglis, or Robert Morris—they are just younger than Warhol was. They look at an older artist being fragile, vulnerable, effeminate—and for them that must have been pretty shocking.

KOESTENBAUM: This is an endlessly fascinating, ineffable, mysterious subject: how did (non-gay) sophisticated New Yorkers in the fifties perceive gay people? I like to imagine Jackie Kennedy, how Jackie Kennedy thought of gay people in 1963, as a perfect litmus test: I imagine she’d have felt a split between a homophobic understanding of gays as pawns and, therefore, pathetic, but also an understanding that they were her true, her destined collaborators. And I think that this double consciousness, for Warhol, a consciousness of being scapegoated yet elect, was already present in the fifties. I’m sure it was present in Hollywood as well, where there were just tons of gay people around and many of them were femme.

BIESENBACH: There is the idea of being closeted, or needing to be in the closet, and the idea of trans being a spectacle. We’re sitting in a diner, right now, talking, and the person who is the maître d’ wears high heels and is walking us to the table like a catwalk. I think younger people, at least in Western metropolises, have no idea what it meant to be in the closet.

Torso (Male Genitals) (1977), acrylic and silk-screen ink on linen. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

KOESTENBAUM: That’s why I think this show has a powerful message for contemporary audiences. And I feel that Warhol always needs rescuing, still, from those who would minimize him as interested in fame in a superficial way, or who don’t understand his textural sophistication, his sophistication with objective material, the fabric of art—film, media—Warhol’s quest for a queer medium-specificity. (Think of the conceptual mileage he found in the very notion of the silk-screen.) Or his gender politics—I think it would be very easy for people to have a more restricted and not open-minded reading of his relations with Edie Sedgwick. Lots of Warhol detractors go down that path.

BIESENBACH: Did he have gender politics? Or was he just a vampire exploiting everybody, sucking everybody’s blood out?

KOESTENBAUM: (Laughs) No, I think he was—well, in the way that people, before there are names for things, are forced to embody those things without the names—he was a gender theorist on the go, performing daily experiments.

BIESENBACH: That was a time when gay guys had to be in the closet and be around alibi women or even marry them to present them to their relatives in Texas. Looking back from today it looked like a masquerade.

KOESTENBAUM: I think Warhol was too far gone for that. You know, he was just so… odd. And I think his behavioral oddities paved the way for our era of more enjoyable gender dysmorphia, of gender broken open and savored for its pliability. I don’t want to use words like “autism,” but he had an unusual interpersonal style, and he was neurodivergent in some basic way. And that was a prequel to his plunge into gender flux. But his primary period of social strangeness—his neurodivergent foundation—made his gender flux less of a stigma issue than it might be for somebody as well-socialized as Halston, that enviably smooth operator.

BIESENBACH: Also, Warhol’s body was put together again. So, when you look at photographs of his torso, he looks a little bit like Frankenstein being sewn together. He was an artificial body. In a certain way he was also a person with a disability.

KOESTENBAUM: Yes, absolutely. And I think that also he was differently-abled in terms of his relation to conversation, to silence, to being seen in public. Consider his relation to the camera as a prosthesis. Consider the Screen Tests as a record of neurodivergence. I think even the fact that the films are slowed down—you know, they’re sixteen or eighteen frames per second, the silent ones—reflects that divergence from the drumbeat of regular gender. Not that gender, even at its most normative, could ever be considered metronomic…

BIESENBACH: So he had these studly men that looked rather straight. So he was definitely the girl in that relationship?

KOESTENBAUM: Yeah. Jon Gould. And Jed Johnson.

Blow Job (1964), 16mm film, black-and-white, silent, 41 minutes at 16 frames per second. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

BIESENBACH: They looked like studs. You had these straight-looking all-American boys and he was the not-so-straight-looking all-American girl. And that’s a fantasy also, right? That’s a Cinderella fantasy about the prince. They were princes, no?

KOESTENBAUM: Poor Little Rich Girl would be very interesting in this regard, I think, as would certain reels from Chelsea Girls that highlight indigence and wealth. I’m thinking of Brigid Berlin—kind of atopic for this show—but one gets a bittersweet sense of her wealth. It’s interesting how finances and money play into what you could call the conceptual work with gender that Warhol did in his career. You know, “business art” is part of this Drella phenomenon as well. And you can think of capital as also vampiric.

Studies for a Boy Book (1956), offset lithograph on paper. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

BIESENBACH: Part of it is self-centered fear, or existential fear. I think he inherited fear from his family. And there is a lot of religion in it. In the context of organized religion, you were not allowed to be fluid in any way—gender or otherwise—because you had a God-given body and you had to fulfill your God-given role.

KOESTENBAUM: But a lot has been written about shamans and third sexes in indigenous cultures. And not only about drugs and altered experience, but about gender-liminal beings and religion. So Drella’s gender-morphed spiritual practice is a kind of folk religion—but I think that his Catholicism was also a folk religion.

BIESENBACH: He was very transgressive in how he was a camera eye and how he was a pornographic eye and how he was a vulnerable eye, but also an active eye. It’s almost an eye that touches you. When I worked on the Screen Tests show, you see people are touched by the gaze. They cry, they don’t know what to do, and they leave. It was a brutal camera looking at you.

Jean-Michel Basquiat Six Polaroids (1983), Polaroid. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

KOESTENBAUM: In A Thousand Plateaus (1980), when Deleuze and Guattari discuss Cézanne (in a passage I’m very fond of), they bring up the notion of “close-range vision,” or haptic sight, when it seems that the eye is touching, bit by bit, the terrain it slowly sees. I’m also thinking of Merleau-Ponty’s essay about Cézanne, which I haven’t read in a long time, but what you’re saying about the gaze, the touch, reminds me of haptic sight. Warhol was bringing out the haptic feature of looking, a dimension of upcloseness that is subliminally present in a lot of art that we care about. I could make a list of the up-close artists, the haptic bunch… And not that Warhol needs ennobling, but haptic sight gives us a way of understanding the lineage of his touching gaze apart from the pornographic genealogy. I think the pornographic genealogy and the Cézanne genealogy aren’t that different, if you take the long view. But for most people these genealogies are diametrically opposed. Those two kinds of gaze—the Cézanne-trained eye, and the porn-trained eye—imply different audiences, even though Warhol’s work and the work of so many artists post-1945, or even way earlier, partake of both camps.

BIESENBACH: It’s kind of interesting when you think about John Waters dislocating his gender fluidity to somebody like Divine. It’s a projection out of the body onto another person, whereas Cindy Sherman projects her gender fluidity onto an alternate version of herself.

KOESTENBAUM: Yes, exactly. That’s interesting. Also not just across gender, but across other substances.

Untitled (Golden Boy) (1957), ink, gold leaf, pencil on firm, chamois-colored drawing cardboard. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

BIESENBACH: I wonder if Warhol was actually aware that he looked like a puppet. He looked like a Hans Bellmer puppet, or like a Cindy Sherman figure.

KOESTENBAUM: Yeah, he does. Reticulated. Morselled. Atomized. Compartmentalized. Comically mechanized.

BIESENBACH: And I wonder how aware he was of how artificial he looked. He plays with it with the wig. But was he aware that the wig that he normally wore was as artificial as any other Halloween thing? It didn’t look like a piece of a body. It looked as artificial as a silver pillow. It was an exploding silver pillow on his head.

KOESTENBAUM: I wrote a piece for Artforum about a show at the Whitney that featured vitrines containing Warhol’s toiletries. I was fascinated—in terms of the wig—by what you might call the prosthetics of Warhol: his supplies, his perfumes, and his equipment as manifestations of that mechanized, reticulated quality that you’re talking about. He gave us an education in how to be artificial, how to enjoy separability, the way a puppet is articulated, its separate parts enunciated, syllable by syllable.

Mick Jagger (1975), acrylic and silk-screen ink on linen. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

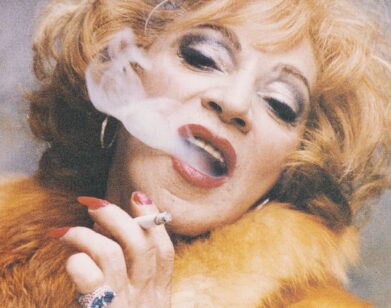

BIESENBACH: I grew up pretty isolated in the German countryside and in a monastery school, which makes a huge difference. And so I never really understood drag and trans and all of these things. Relatively late in my life I understood it in a certain way. One of my best friends, Jörn Weisbrodt, married Rufus Wainwright, and I was their bridesmaid. I was throwing the flowers. (Laughs) Did Warhol want to be a girl? Do we know that?

KOESTENBAUM: No, we don’t. I think the question is—and this is a little bit deconstructive, forgive me—but does “want,” as a verb, split the “I” that’s the subject of the wanting? If you say “Andy wants to be a girl,” it’s no longer a singular “I” that wants. It’s no longer true that “A wants to cross over into B.” The act of wanting anything, you could say, splits one up. And that splitting leads us to Godard and capitalism. I’m thinking of, for example, Two or Three Things I Know About Her; those indictments of the commodity are all about splitting reality into individual articulations. And what Warhol does—or even Straub & Huillet, who dislocate events and actions from their original time zones—those actions of estrangement really take apart the subject. So yes, my answer would be that Warhol absolutely wanted to be a girl. All five Warhols wanted to be a girl. (Laughs)

BIESENBACH: Or five Warhols wanted to be five different girls?

KOESTENBAUM: Five different girls.

BIESENBACH: I think to a person who is a digital native living in the twenty-first century, Warhol might look like a medieval Carnival figure, right? Because everything is visceral, nothing is digital, nothing changes in your body stimulated by hormones…it’s a very stable analog. For example, at the time, in the seventies—I remember this as a kid—women in Germany used to wear wigs. I remember that my teacher had a blonde wig, and she would sometimes be this other person with it. The wig as a prosthetic was just more common at the time. Younger people don’t really see those kinds of obvious wigs so much anymore. It’s interesting that Andy moving between gender expressions, he was moving between a body that was whole and violated. And in a certain way he was also very intergenerational considering the people he hung out with.

KOESTENBAUM: He was also trans between living and dead in so many ways. You could say… geographical displacement, father’s death, a body that felt alien, a fascination with stillness. Just a refined, palpable, omnipresent awareness of death-in-life, which is a religious comprehension. Like incarnation and Jesus, being this intersection-point of living and dead. An eroticized body that is the point of touch (hand to hand, wound to wound) between the divine and the human.

BIESENBACH: It’s also the living and the still, the moving picture and the still picture. Photo is death, and movie is life.

KOESTENBAUM: I think this is true of very productive people in general, that their temporality is different because they have succeeded in compartmentalizing time. I imagine Warhol walking around New York City and always working: He’s meeting at Interview magazine, he’s taking pictures, he’s always looking. So the day, to him, is fractured or fragmented into all these little parts of temporality. I’m thinking about the writer Joyce Carol Oates, who fascinates me. I believe that she’s written more than any serious writer alive now. When asked about her productivity, she once said (I paraphrase, perhaps conflating different statements she made in various interviews), “Everybody experiences time differently. I spend a lot of time doing nothing.” And I just think that there are people—I mean, you must know lots of them, who…

BIESENBACH: Have a different temporality, a different productivity. Yeah. It’s also fascinating that there are a lot of different body morphisms in Warhol, lots of wigs and lots of characters, but there is never a beard, never even a trace of a beard, which is actually pretty stunning, right? Because you look at Duchamp, you look at other artists, and that’s always something that they play with, but he never played with a beard.

A Gold Book by Andy Warhol (1957), hand-colored litho offset prints. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

KOESTENBAUM: I think that is also part of a kind of disembodying, demasculinizing discourse around gay men of that time, where the sometimes sexily-obvious virility of gay men was somehow ignored. I think of somebody like Rex Reed in Myra Breckinridge (1970), playing Myron. He looks really masculine, but in a way he’s the epitome of swish. And that’s always been, for me, the strange paradox of pre-Stonewall: a welcome spectacle of a swishy guy who wears purple and who has really hairy, thick-boned wrists—some of those early “flamers” were he-men. Like the guy in Dressed to Kill (1980), right? Or is that a different story altogether, best steered clear of? We, or the general public, or the homophobic chronicler, seem to have a culpable willingness to erase the secondary sexual characteristics of men like Warhol and not accord them their hunkiness.

BIESENBACH: So you have Lynda Benglis with a prosthetic penis, and then you have Robert Morris in his fake leather outfit. I don’t know if it’s actually fake, I always thought it was fake. Does this have anything to do with Warhol?

KOESTENBAUM: There’s one discourse—and this is kind of a gay discourse—that says you can accurately read everything through the pants. But then there’s the trans discourse that says the more you see, the more likely it’s a fake. You know—a sock. It’s this strange puppet of understanding a body through these different zones: the top, the bottom, back, hips, the beard. It’s segmented looking.

The Rolling Stones “Sticky Fingers” (1971), offset lithograph on coated record cover stock, metal and fabric. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

BIESENBACH: It’s very interesting that he kept himself so clean-shaven. And the lovers were discreet. I’ve not yet come across any description of how he was as a lover.

KOESTENBAUM: A book that I relished in my research was Patrick S. Smith’s Andy Warhol’s Art and Films. It’s a compendium of interviews with people Warhol knew. That might be where I read the anecdote about Warhol taking sex lessons. Or I might have read it elsewhere, in an interview with Vito Giallo. And I can’t reliably link you to any of this, but I feel like I’ve read statements by eyewitnesses that implied that Warhol was much more sexual in his body than the usual understanding we have of his erotic comportment. I seem to hear, or remember hearing, a chorus of phantom voices asserting Warhol’s sexual viability.

BIESENBACH: Many felt the need to describe him as asexual. He was so visible but not straight, so he better be asexual.

KOESTENBAUM: But you know, he had a traumatic yet liberating experience where he stopped caring—a conversion to a bemused, wakeful stupor. It’s mentioned in Popism. He stopped caring in the early sixties, or was it the late fifties? And he said that the relinquishment of caring made everything possible for him. I remember thinking he stopped caring because he had been jilted on a trip to Europe. And after that the plastic persona took over.

BIESENBACH: Why was that? What was the reason that the plastic persona took over?

KOESTENBAUM: Something happened on that trip to Europe, where (maybe?) Charles Lisanby jilted him. They were traveling together and this boyfriend of his jilted him—

BIESENBACH: Hurt him, basically?

KOESTENBAUM: Or something—just dropped him, was no longer interested, broke up with him. And after that Warhol stopped caring. And I don’t know how true that story is; it’s a movie-biography notion of a plot point—you know, romantic heartbreak creates transformation—but I always believed it. And when I saw pictures of Warhol in the fifties, he seemed like a different person. He had not figured out his look, his remoteness. He was still flipping through different personae, searching for the right one.

BIESENBACH: What is fluidity for you?

KOESTENBAUM: Well, in terms of the nomenclature, I know that on sex apps, or when people declare their pronouns, people say “nonbinary,” or they say “she” or “he” or “they,” and there is a difference. I know straight men—men who are erotically engaged with women, who present as masculine—who call themselves nonbinary. In part that might be an ideological statement, or a good-faith expression of a wish, an intention, a stance. A hypothesis? Or a speculation? Or maybe it’s actually a mimesis of something that they feel? I enjoy all names that people put to their varied experiences. Without strictly identifying at this moment as non-binary or trans, I can attest that when I was a kid I was always afraid of being thought a girl, or femmy—

BIESENBACH: Well, right, we grew up being afraid that people thought we were effeminate; I remember that.

Male Upper Torso (ca 1950s), graphite on Bond paper. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

KOESTENBAUM: Yeah, it was a big deal. It was a very big deal to be a boy whom strangers mistook for a girl. And I didn’t understand gayness when I was a kid, but I understood being mistaken for a girl, and that seemed like a terrible undoing of my being.

BIESENBACH: Yeah, and you see your parents being embarrassed. It’s so painful.

KOESTENBAUM: So masculine legibility has been something I’ve striven for, and I often wonder, if I were to look into my psyche, or my wishes, what would be the map of my—you know, my gayness, straightness, transness? I remember when I was a kid—I think maybe we all did this—sitting down on the toilet and tucking my penis between my legs and being shocked how easy that was to do. (Laughs) Just tuck it in and then “Oh my God!” I always loved women’s clothes—I mean, who doesn’t? They’re so beautiful. And I’ve never known what to do with that love. If I were straight, or if I had chosen to stay that way, I would have the pleasure of girlfriends who wore beautiful clothes, and I could be near that pleasure. Or I could wear women’s outfits privately like Martina Kubelk in her self-taken photographs (I saw them at Galerie Suzanne Zander). Or now I could wear women’s clothes on the streets of New York. But none of the routes have explained to me: What would be the fulfilling way to have that perfume of women’s clothes surround me in a way that would be emotionally transporting? And it’s not fetishism; that’s one of the punitive words that we’ve used in the past to describe, say, what I feel when I look at mesmerizing pairs of women’s shoes.

BIESENBACH: Yeah. Desire, or beauty, or—

KOESTENBAUM: It’s just—my whole being is flooded with a wish. And I think, “Wow, is it because I want to wear those shoes?” And I really don’t think so. I want to be near them. They excite my will to live. They activate my imagination and speed me up. They verify my humanness. They also verify my happy alienation from the human—my mechanicity.

Portrait of Jean-Michel Basquiat as David (1984), acrylic and silk-screen ink on canvas. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

BIESENBACH: Was it easy during Warhol’s time to do a sex change?

KOESTENBAUM: No, it would’ve been bad. Also, difficult to obtain.

BIESENBACH: Socially as a stigma? Or—

KOESTENBAUM: He’d be erased. I think being transgender in that era was a truly vanguard, isolated position. Not within Warhol’s ken. Not the career path he had in mind. There are jokes and scuttlebutt about certain Hollywood stars who have been presumed to be transgender. Plenty of gay men would say that Mae West was a man.

Muhammad Ali (1978), screen print on Strathmore Bristol paper. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

BIESENBACH: I remember when I first came to New York, which was in the late 1980s, and then a little later when I started working at MoMA PS114—that must have been the early nineties already—Alanna Heiss took me to a meeting at Edelweiss on the West Side Highway. I was still a little bit undercooked, underdeveloped. (Laughs) And I remember she took me to Edelweiss, and they had, like, a whole fleet of beauties.

KOESTENBAUM: Yeah, amazing.

BIESENBACH: I think there is something about drag and costume and playing a different role that is almost religious. As a child, I grew up with Cologne Carnival. Carnival allows you to roleplay. During Carnival you can be the person you cannot be otherwise. At Edelweiss you could be somebody else. And I think there is something about Warhol that is a masquerade. He played that vulnerable female role almost like a role in a ceremony. “I can be that for you.” And then he could be that for his all-American boyfriends. It’s like an offer. It’s something one wouldn’t understand today anymore. We say “fluid,” and fluid has something—

KOESTENBAUM: Yeah, you’re right. Right away when you said “fluid,” I imagined something like Ophelia, or the Rhinemaidens, or all the pre-Raphaelite imagery of women in water. And Narcissus. All those metamorphic, mythical personae like Daphne, who turns in a tree when she’s looked at. All those transformation artists. They opted for transfiguration because they were tired of running away.

BIESENBACH: I don’t look at performance as a product but as a process on the way to something. So I see Warhol as a performance artist in Pop. Because “art is life, and life is art”—that was the theme of the Marina Abramović exhibition. So his life was his art, his art was his life.

KOESTENBAUM: And he was always present.

BIESENBACH: “The artist is present.” And so I see him as a performance artist in that way.

KOESTENBAUM: He had definitely come to performance art by the time he was at Area doing his Invisible Sculpture. And if you compare him to Jonas Mekas—for Mekas, it was always the film that was sacred. And dailiness was sacred, but dailiness was the pretext for the alchemic act of filming. He called himself a filmer, not a filmmaker. And in a similar way, Warhol was a filmer, but his was a performance of mere looking, of numinous looking. Mekas’s camerawork is also performing the act of seeing, but his work is about film. Warhol loved the fact of film, its ease, its miraculous liquidity—but I’m not sure he loved film qua film in the same stubborn, humble, faithful way that Mekas did.

BIESENBACH: And let’s not forget about Jack Smith. And think about the Factory, about all of it. Think about Couch. I think he was very much a performer but not understood as a performance artist. When I started as a curator, artists like Joan Jonas or Carolee Schneemann were often described to me as video artists. And then when I helped start the Media and Performance Department at MoMA I actually said, “No, they’re not video artists, they are performance artists.” And that was a late revelation in my understanding. And I think that has not yet happened for Warhol, that he is seen as a performer.

KOESTENBAUM: I love that. As a poet I would like to ask if figures like Bernadette Mayer or Frank O’Hara, two poets who used words to navigate the world and to create new worlds, could be designated as “performance artists.” (Is “performance artist” as a category more elevated than “poet”?) Or maybe it’s less valuable to grant that role to them, because the fact is that their words on the page are what ultimately matters. Their words, as mobile sources of energy and sound and significance, approach the condition of performance.

Mick Jagger (1975), screen print on acetate and colored graphic art paper collage on T.H. Saunders paper. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

BIESENBACH: I was very close to Susan Sontag, and she was a little bit of that.

KOESTENBAUM: Absolutely, because you feel in her written work the sense of her embodiment and her moving through things.

BIESENBACH: She was also a persona larger than life. We would often go out to places and people would recognize her. Warhol was recognized; he was a public person. And, of course, she was very aware she was Susan Sontag, so she also had a character, and she would always make sure she was not out of character. But sometimes we would go out at night and she would not be recognizably in character—like wearing a scarf wrapped around her head—and nobody would recognize her. And so her life had a performative quality, because her work was not only words. And I think with Warhol, this show might bring the performativity of his life as art a little more into focus, which I hope is meaningful.

KOESTENBAUM: I agree. The primary argument of my Warhol book was that he gave us in his visual work—film and paintings—an experience of his embodiment. It was a transmission of what it felt like to be him. His work wasn’t a narrative about him; his work was the actual experience, which included stillness, desire, doubling, remoteness. I would particularly agree with your statement about Warhol being a performance artist if part of his performance involved the transmission of an affect and a physical experience into the viewer. So that he is—and this is truly vampiric, in a way—he is literally infusing us with his performance. So it’s like olfactory art, it’s a sensual absorption. But that’s the thing with Warhol: It’s not just retinal. Taking it in and slowly surrendering to the revelation, “Oh my god, this is hot, but it’s not porn. Or is it? Is it religion, philosophy, landscape, political theory, transcendence, documentary, medicine?” And so—well, obviously it will be a great show.