IN CONVERSATION

To the Artist Hugo McCloud, Even Dead Flowers Are Worth Painting

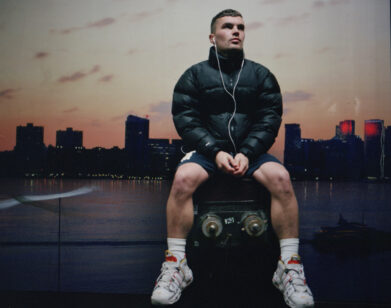

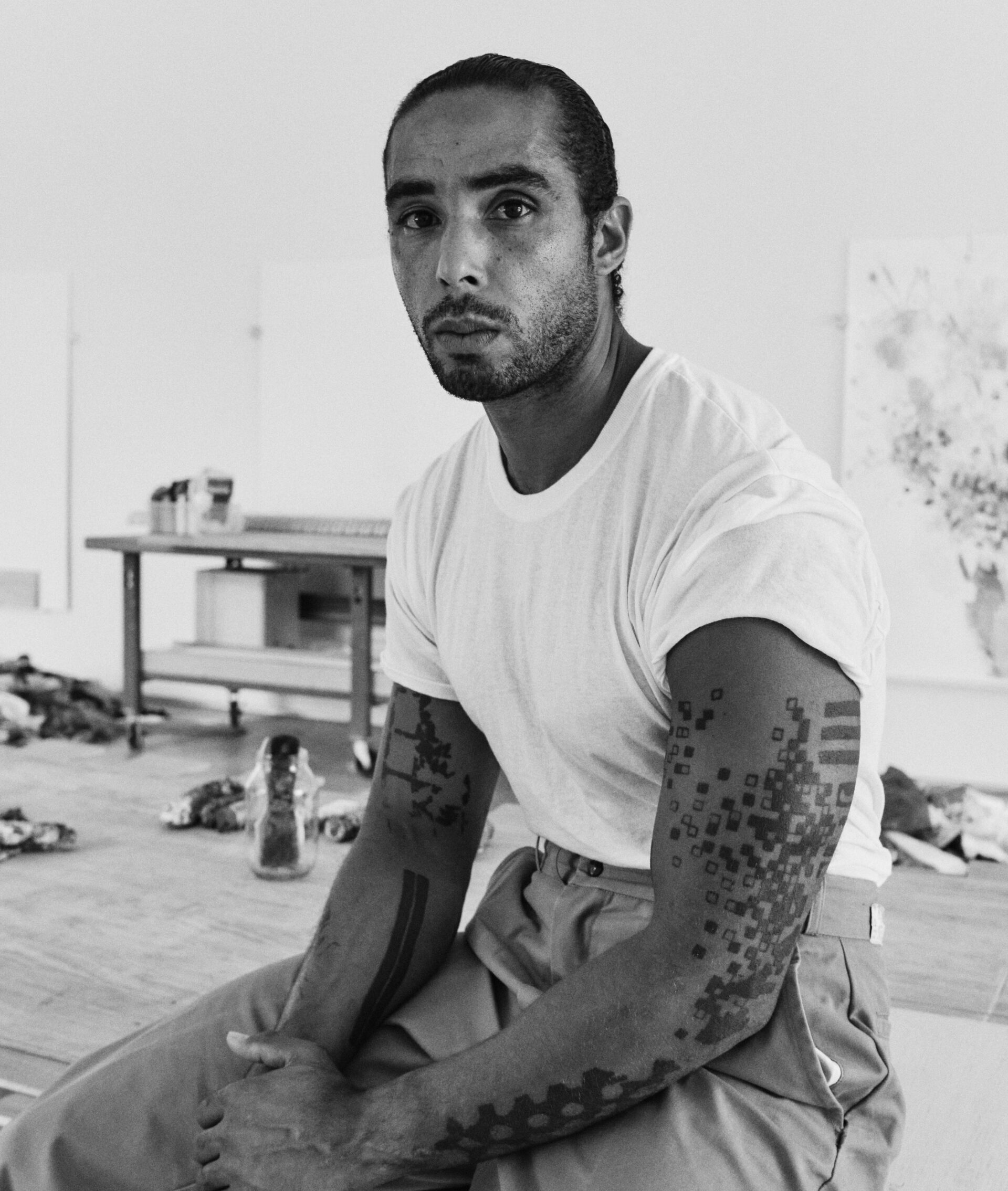

Hugo McCloud, photographed by Enrique Leyva.

Hugo McCloud‘s solo exhibition As For Now opened last month at Sean Kelly, featuring works that utilize brighter colors and compositions, a shift in tone from the artist’s recognizable abstract metal works. Using aluminum foil, single-use plastics and other industrial materials along with oil paints, McCloud zooms in on a series of flowers throughout various stages of their life cycle. Also included are works part of his Burdened Man series, depicting manual laborers straining over their work, a process that, fittingly, entails the artist’s own arduous process of integrating hundreds of pieces of cut-out plastic into the canvas. Reflecting on the intricacy of his craft in a conversation with his close friend Aurora James last week, the artist explains, “The reality is, I feel inadequate to the point where I have to put such levels of labor and effort into these things for them to be worth anything.” He went on: “I had to create all these layers to find value in it and to accept the work itself.” On Zoom, the pair talked about grief, beauty, and the evolution of McCloud’s subjects.

———

AURORA JAMES: My first question for you is—obviously the plastic works have evolved. You started doing the sacks and then the portraits of people and, in this most recent show, you’re doing flowers. Do you feel like there is an emotional thread at all? And how is the evolution of the plastic works connected to how you’re seeing the world, or is it not?

HUGO MCCLOUD: The way that I see the world is reflected in both the plastic and the tarp works, and the abstract and the figuration and the flowers. It’s pulling from both the positives and negatives that we’re continually facing and figuring out a way to juggle those differences and trying to find peace and acceptance with them. The things that I’m addressing or dealing with are not always the most positive, but I try to illustrate them in a more glorified way.

JAMES: Right, the ways that can be perceived as more beautiful.

MCCLOUD: Yeah, or maybe it’s a surface coat to pull in the viewer so that it’s not so hard to swallow right away. But it’s always been my language of how to tell my story. I feel like it’s probably the same way that you’re telling stories working with different artisans and craftsmen around the world. Some of the realities of how those things have started are difficult, but then you’re creating something that is desired and beautiful.

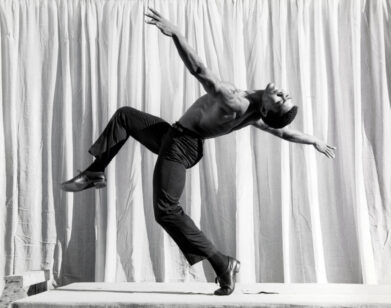

Turning point, 2024 aluminum foil, aluminum coating, and oil paint on tar paper 78 x 108 x 2 3/8 inches. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles.

JAMES: Yeah, that’s fair. We have a common thread in that we’re people who have gone through some difficult situations and are still persevering. The thing that really stuck out to me in the stamp paintings is the immense physicality that went into creating that work, because you were taking these stamps and hammering them. I remember I would sit and watch you do that for really long periods of time, and seeing someone exert that much physical energy… I mean, it’s so easy to look at it and go, “Oh, this beautiful pattern that has this great color story,” but in reality, when I look at those works, it’s a story of a man who’s trying to keep it together and is going through all of these different phases. But then suddenly, you were using these plastic bags that were so light and translucent. So I see two pretty distinct transitions in your body of work: one is from your physical labor, using and wielding heavy materials, to then a lightness of materials. My question is, emotionally, do you feel those changes? Are you consciously setting out to depict the change that you’re having?

MCCLOUD: I’ve come to a realization in the last couple years, having done a bunch of work on myself through different programs and therapy. I’ve realized that everything I’ve created is me trying to find myself within the work. At the same time, everything that I’ve created is part of myself, meaning there is the labor, there is the fragility and the beauty of the flowers, and there’s also beauty in the dirt and the grime of even the tar. As far as the labor that you mentioned, the reality is that I feel inadequate to the point where I have to put such levels of labor and effort into these things for them to be worth anything. I had to create all these layers in the process of creating my work to find value in it and to accept the work itself. When I go from the abstract aggressive works of the tar to the softer palettes and elegance of the larger plastic works, I do think it’s the process of evaluating myself. The evolution of those things is me accepting the evolutions that I’m going through too.

JAMES: It feels like what I’m hearing you say is that in the earlier days with the tar works, you were placing a lot of the value that you were bringing to the work in your physicality?

MCCLOUD: The reality is that I was creating that work and that language because of insecurity, not having a background in art or art history or education, not having the connections. So I almost had to fabricate a story of why I’m doing all these things. This show is interesting because I had to let all of that go and allow myself to go into the studio without direction, really.

JAMES: Yeah. So much of your work is about feelings and unprocessed feelings that sometimes it can be really hard to articulate. But also, as a viewer of the work, it’s like, there are the flowers, but then there’s also the people in India who were picking and packing the flowers. I think that’s a narrative in your work like, “You can enjoy this, but remember all of the work that I had to do, and all of the work that these other people had to do.” And I always think about where the work lives. I feel like your work needs to be in major institutions, because we need to be having those conversations about it.

April 24, 2024. Oil paint and single use plastic mounted on panel painting: 20 x 20 inches. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles.

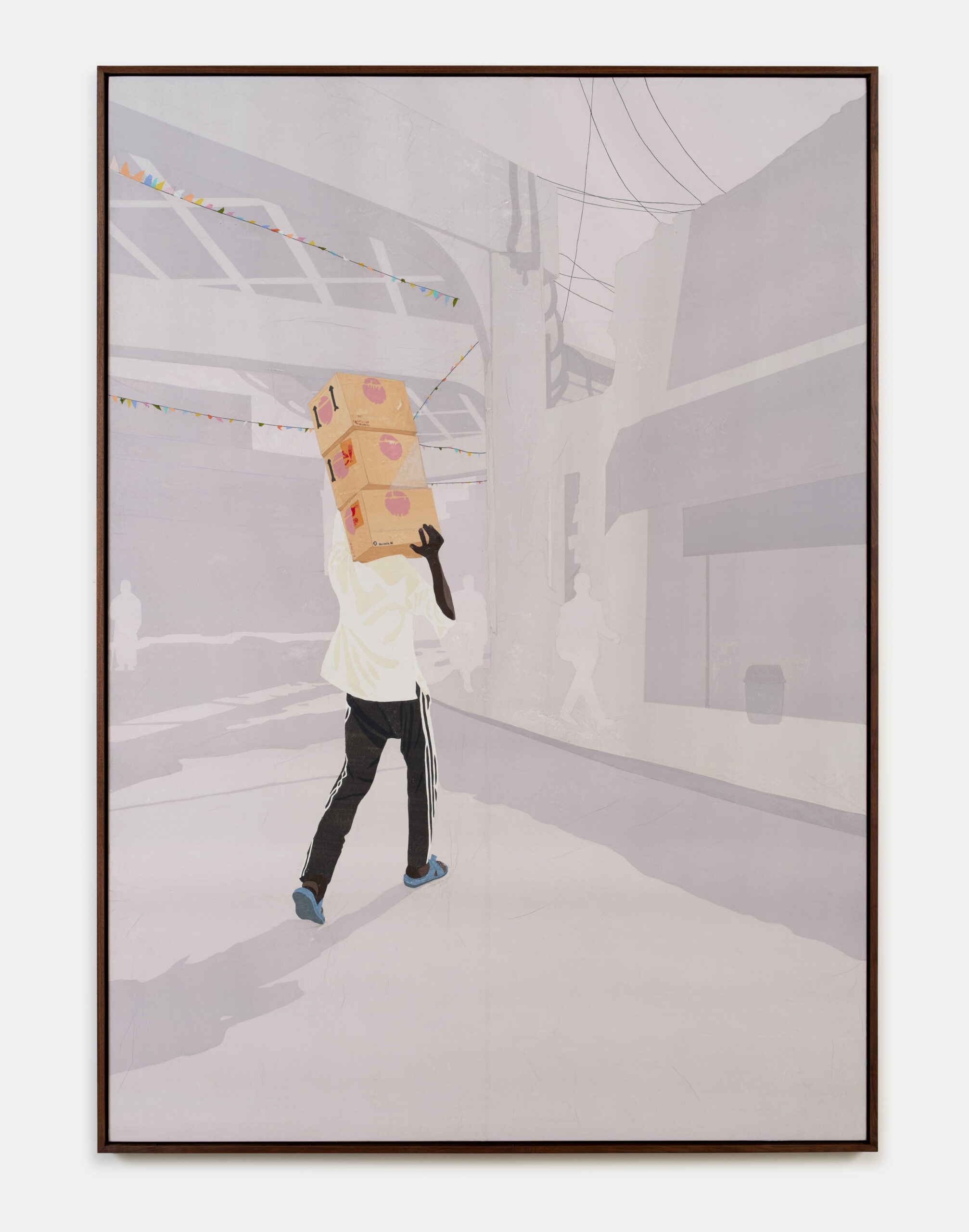

MCCLOUD: Yeah. When I started doing The Burdened Man I asked myself, “Why am I attracted to this struggle to the point where I find an aesthetic appeal to it?” I feel like it’s in my abstract work where the burden that most of these people were carrying was my own. I feel like a lot of portrait artists, unless it’s an exact copy or a replica of a photo, paint figures and characters that have a somewhat similar look to themselves. It’s almost weird in a way, like they’re painting themselves. It could be a man painting a woman, but there’s still some characteristics that connect that person to the characters they’re painting. Whether my work ends up in institutions or ends up in the garbage, my work stays true to how I visualize the world as a Black man and how I walk through this space. I never felt like I needed to convey in my message that I’m Black. I feel like that is what I am, and if I’m painting flowers, I’m painting flowers as a Black man. I walk on this earth as that.

JAMES: I’m curious, do you find flowers more beautiful before they bloom, while they’re blooming, when they’re dying, or when they’re dead?

MCCLOUD: It’s case by case. Sometimes when you buy a fresh flower that just bloomed or opened up, it’s amazing. It’s like, when you look at life, there’s all these different moments where you have the same emotions. You have these moments that happen continuously, but you’re under different emotions. So when you’re under different emotions, you see that thing in a different way. I don’t find any particular moment within the lifespan of a flower to be more beautiful than not. That’s why I try to illustrate all these different phases. Because to me, there’s no difference. All of that is also how we are experiencing life.

JAMES: Right, yeah. I remember I was texting you photos of flowers the other day, and you literally responded, “These flowers need to die more.”

MCCLOUD: But again, maybe I was in a space of interest where I didn’t want anything fresh.

JAMES: One-hundred percent. And then today, you walk in and you see this flower that’s in the prime of its life, and your face lit up and you’re like, “This flower is amazing.” Do you ever get mad at the flowers for dying?

MCCLOUD: No.

JAMES: I do. Sometimes I’ll go back to the store and try to find the exact flower, but I can’t and I get mad.

MCCLOUD: I don’t get mad, but I get upset with myself that I don’t have attachment to it, where I can let it go so easily instead of actually having any of those emotions. It’s like, I can fully appreciate it for what it is in that moment and, at the same time, there is a question in my head of, “Why do I not miss that? Or why do I not want that?” It’s painful when you break that down into other aspects of life, for sure. Well, I don’t even know if painful is the right word for me.

JAMES: Do you feel guilty?

Installation view of Hugo McCloud: As for Now, Sean Kelly Gallery, New York, 2024. Photo by Jason Wyche. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles.

MCCLOUD: No, it’s troubling. Because it makes you feel passive, like stuff can just flow through and there’s no–

JAMES: Are you flowing through it or are you compartmentalizing it because it’s too painful to wade through?

MCCLOUD: That is something I’m figuring out.

JAMES: Right, like I’ve cried about my dad dying exactly one time, but I’ll also cry about the flower dying, about Mr. Chow’s best friend going on vacation, about the SCAD fashion show. I was crying for hours earlier today. Sometimes things are too painful to even begin to process so instead you just carry it around.

MCCLOUD: Well, I think when you look at the plastic works and stuff that I’m doing with Burdened Man, that is also this continual weight I’m putting on my shoulders. It’s like what they say fighters go through, they call it fighters oppression. It’s like, you finish something major and it’s kind of anti-climatic and then all of a sudden you’re like, “What am I doing with my life? What’s next? I’m not doing anything. I’m just wasting time.” I think it comes down to a space of not knowing how to celebrate yourself and your accomplishments. I think that goes into a lot of what we’re doing to ourselves through social media, the quickness of things. You think about a flower too; you look at it one day and then you feel like the next time you look at it, it’s dead. But in reality, that could have been a week span that you didn’t really fully enjoy all the different moments within that lifespan. You almost only focus on the beginning and then the end.

Visible exertion, 2024. Single use plastic mounted on panel painting: 84 x 60 inches. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles.