IT'S PERSONAL

Three Girls Take One Gallery in a Sensual Show at OCDChinatown

Nash Glynn, the 30-year-old painter, was sitting in the office of her parents’ house in St. Petersburg, Florida, swiveling on a chair between a laptop and a full-length mirror, just like she does at her easel. Sam Penn, the 24-year-old photographer and model, was in her Lower East Side apartment, preparing to run errands in vintage Miu Miu because she does not own normal clothes. Ser Serpas was heading home from her studio in Paris, where the 28-year-old artist and poet is living. I was still in bed, laughing.

The girls were talking about their newly opened group show at OCDChinatown. Funny, because not talking about it, not even saying what it is, is the clearest implication of the title of the show: It’s Personal. A great little stock phrase, deceptively banal, that to me betokens the deep, the ulterior, the inexplicable, and the pointless. It refers not only to secrets, but to what words can’t (yet) describe. Nash, who curated the show with Sam’s help, thinks explaining yourself is uncool, anyway. Ser is notoriously never tongue-tied, and took two seconds to decide that the themes of our discussion, though not necessarily of the works discussed, were friendship, autofiction, and afterimages. Three is a crowd, which is one reason I cut my lines from the edited transcript. The other reason is selfish: so I could enjoy it, like you will.—SARAH NICOLE PRICKETT

———

NASH GLYNN: I wanted to talk about my painting of the roses in the show, because it involves both of you, but first I need to grab my coffee.

SAM PENN: Ser, where are you coming from?

SER SERPAS: I’m in a car from the metro station to my studio.

PENN: I thought you couldn’t take the train alone.

SERPAS: It’s crazy. I’ve been living in Paris for six months and today I had to run an errand and it was the first time I took the train here by myself. I felt like a member of society for the first time ever. [Laughs]

PENN: I cannot believe that, Ser. That’s insane.

GLYNN: So, the roses. One of them I bought for myself and put in a vase with water, and the second one I bought for Ser, when she was here in New York, and she left it on the table at my place, so in the morning I found it wilted and distorted by gravity. I put the two together and—you know, one looked more figurative, one looked more abstracted. The impetus for the painting also came from a feeling I had one day when I was looking at Sam, and it’s a feeling I often get from looking at my friends, because I’m surrounded by muses, including everyone here. The feeling was like, how miraculous that I get to be in the same time and place as this beautiful rose and inhale its perfume and, you know, feel how soft and—anyway, yeah.

PENN: I came over the day before the opening and the roses were still there in the same position and I feel like oftentimes it’s cool to be in your apartment and see the chair right next to a painting of the chair, or the knife in the wall next to a painting of a knife, or the roses… untouched, part of the scene of the apartment.

SERPAS: Part of the apartment is always shifting into the work and then into the show.

GLYNN: I only said yes to curating the show because I thought it would be great for Sam. Then Sam basically took over and did everything, which was great for me.

PENN: Not everything. I asked Ser to be our third.

GLYNN: Three felt right. A triangle is the most stable shape—you know, like the Freedom Tower.

SERPAS: Is that where Conde Nast is?

PENN: That’s where Anna [Wintour] is. She gets to watch over all of us. And I came up with the name for the show, “It’s Personal,” which is the name of a Radio Dept. song. It’s a song with no words, so it could mean anything.

GLYNN: I wanted to call the show “New Works by Sam Penn, Ser Serpas, and Nash Glynn,” but nobody liked that.

PENN: It sounded like a—

SERPAS: Sample sale.

PENN: Then Lana Del Rey made one billboard to promote her new album, literally one in all of America, and put it in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where her ex-boyfriend lives. She posted it on instagram and commented under the picture, saying: “It’s. Personal.” We thought that was a sign.

SERPAS: Everyone in the comments was like, you’re crazy for that, and she was like, yeah. So she had to put up a second billboard in Los Angeles.

GLYNN: Well, she probably has an ex there, too. Don’t we all?

SERPAS: Maybe it’s like with me with my paintings, because I do paint people I’ve slept with but then it’s like okay, if I paint multiple lovers it’s not a fixation, it’s just like… anything goes.

PENN: You should put them on a billboard across from Clandestino.

SERPAS: Yeah, and get sued. Actually no one would sue me, because no one ever recognizes themselves in my paintings. I know how to build up a form from nothing so I can make bodies look like no one’s body, with a lot of stretched-out arms or kneecaps turning into breasts. Sometimes I don’t even recognize myself, if I did a self-portrait long enough ago.

GLYNN: Diaries are like that for me. I open them and think: “I hate this girl, she needs to die.” Sometimes I burn them.

PENN: Have you always kept a diary?

GLYNN: Sporadically, yes. I carry a notebook with me everywhere.

SERPAS: I do phone notes, but I’ve always thought it was nice to have a physical thing.

PENN: I haven’t written in my diary yet this year.

SERPAS: Because it’s Prada?

PENN: Because I’m too worried about what I’m going to write. It’s like opening the floodgates. There’s too much to say. The diary is Prada, and when Sarah got it for me, she asked if I would actually use it. Then she said, “No, of course not, your camera roll is your diary.”

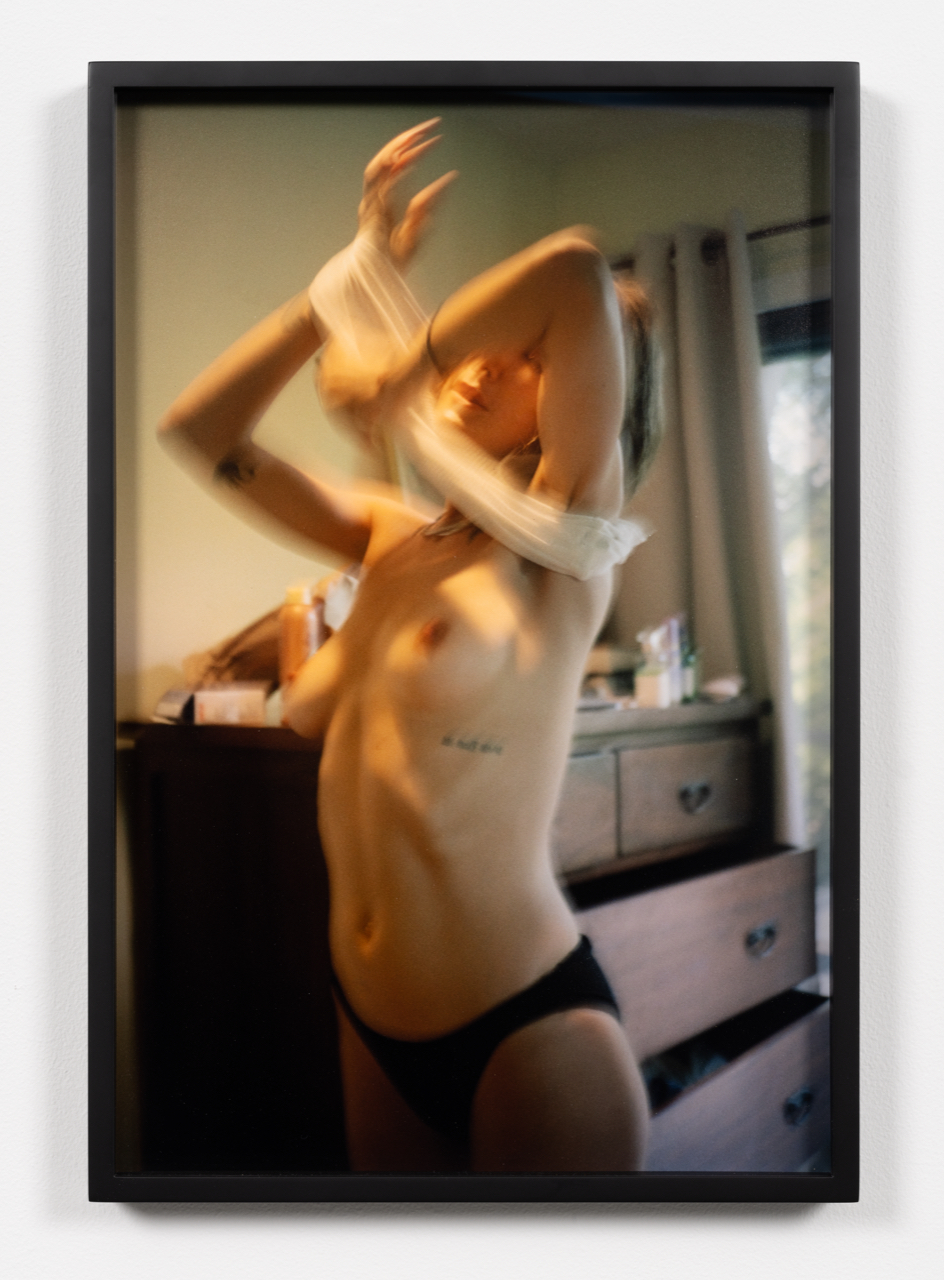

GLYNN: People think photographs are closer to the truth, but they tell one second of a story.

PENN: When I look at a photo I took, I always remember what was outside the frame. Like the photo of Thora in the bath: I can zoom out and clearly see the bathroom where we were, the bedroom we were staying in, the house my family was renting in Philadelphia for Christmas because they’d just sold their home. I’ll never see the rented house again, and I’d have forgotten a lot of what happened there if Thora hadn’t wanted to take a bath, or if she hadn’t wanted me to take the photo.

GLYNN: I feel like every painting, or every photograph, is as much about every terrible and beautiful thing that had to happen for it to be taken in that exact moment as it is about the subject.

PENN: Nash, I feel like the skies in the background are the most personal part of your self-portraits. You’ll be like, “this is what the sunrise looked like after I stayed up all night at a club in Amsterdam,” or what the sunset looked like on the way to meet some guy. What’s the sky in the painting in the show?

GLYNN: It’s the sky in Florida the last time I was here with my family, last summer in the late afternoon, after my boyfriend had moved away. I lost myself and needed to remember who I was, so I came here and stood on a dock and watched lightning storms move. It’s not as dramatic as the sunsets and sunrises in some of my earlier paintings, the ones where it looked like I could fall through the horizon or melt into the clouds or something. Those landscapes were sort of dysphoric. Here I stand out more, I look more grounded. Something changed.

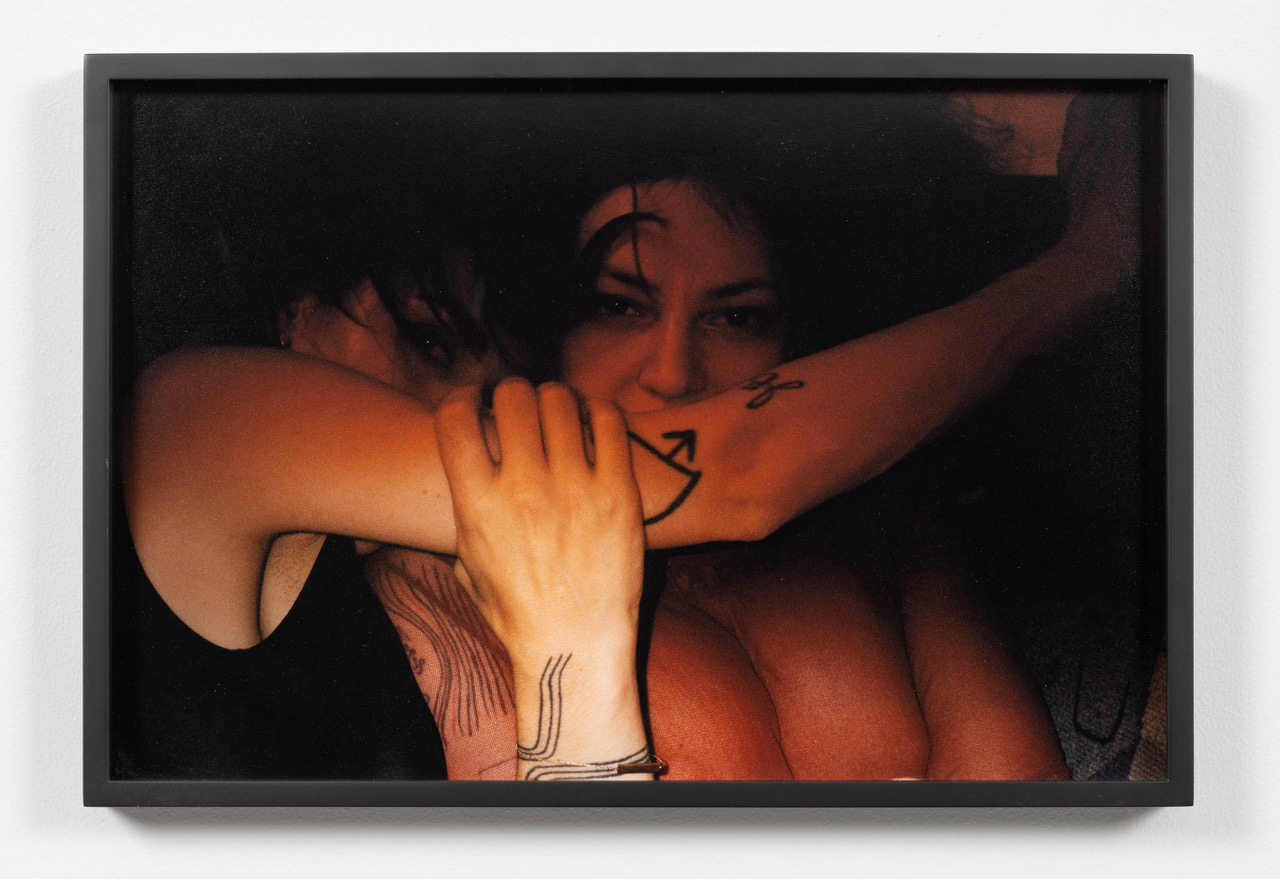

PENN: I think that’s why I like the photo of Sam and Ser in the show, which was taken when they were both in the city at the same time, at this random hotel in Chinatown. There was an awful framed drawing of flowers on the wall behind them, which I took out of the photo in post. I could have taken it off the wall, but my camera was right next to me and Sam’s arm was already around Ser, so I didn’t have time to change anything. The most important thing is getting what I see in front of me in that moment, because a millisecond later it won’t be there. I love how Sam isn’t looking at me, she’s looking behind herself. Maybe I told Ser to look at me. Often that’s the only direction I give, “look at me,” because that’s the only thing I want—the connection between me and the subject.

GLYNN: That, or “heads together.”

PENN: Yes, I say that because the camera I use has a fixed lens, and I’m usually so close to the subjects, so in order to get everyone in the frame, I tell people to move closer together.

SERPAS: How did it feel to present photos like that for the first time as physical objects?

PENN: Cool. It was the first time I did prints on that scale. I usually show my photos online, so it was nice to see them in the flesh. It feels like the only reason I’m able to make a compelling image is because of the connection I have in real life between me and the person I am photographing. I loved finding all the negatives and rescanning them and making something people can see in physical space rather than having the final product be on the internet.

SERPAS: I’m thinking about how to archive all the reference images I’ve already painted and used. I lost all my photos from freshman year in an iCloud accident.

GLYNN: Maybe that’s why I don’t use my phone for reference images. Except for pictures of the skies, all the reference images for self-portraits and still lifes are taken with the same digital camera that I’ve had since I was 16 years old.

PENN: How many nudes of yourself do you have on your laptop?

GLYNN: Thousands. Hundreds of thousands.

PENN: Are they all part of your archive? Like when you die—

GLYNN: I don’t plan on dying. Sam, didn’t we promise each other one time?

PENN: There’s this video from when I was four that begins with me standing next to my little sister who is in a wagon, and as as soon as my Dad starts recording, telling me to push my sister around, I correct him on how he should be holding the camera, take it from him, say that he should push my sister around instead. I think I wanted to be in charge of, and not just a part of, the narrative as soon as I figured out how.

GLYNN: I remember liking being on camera, putting on shows, dressing up. Then, maybe around age five or six something changed, and I started to look away from the camera. I think that’s also when I started painting roses and other flowers.

SERPAS: You know the flowers in Los Angeles that bloom in July, the purple ones that look like women in dresses—jacaranda? I used to make them play the victims in these horror-movie simulations I would do, torturing them and killing them with Saw-style traps.

GLYNN: I would make flowers kiss and stuff and then get burned or drowned.

SERPAS: The stem inside of them would be the soul. The jacaranda, they’re very soft, they feel like flesh.

GLYNN: Mine all had faces—like gardenia, hibiscus. And I made them all princes and princesses.

SERPAS: Mine were princesses too, but they were always fighting.

GLYNN: Sometimes they would die, but then you could go out the next day and pick all new flowers and the story would go on.

SERPAS: Did you ever feel like you were stealing the flowers? The jacaranda were falling everywhere around me except not in my own yard, so I would procure them in a way that was, I guess, clandestine. I still think that when I make paintings, I’m stealing moments.

PENN: Does that feel like a violent thing to you, Ser?

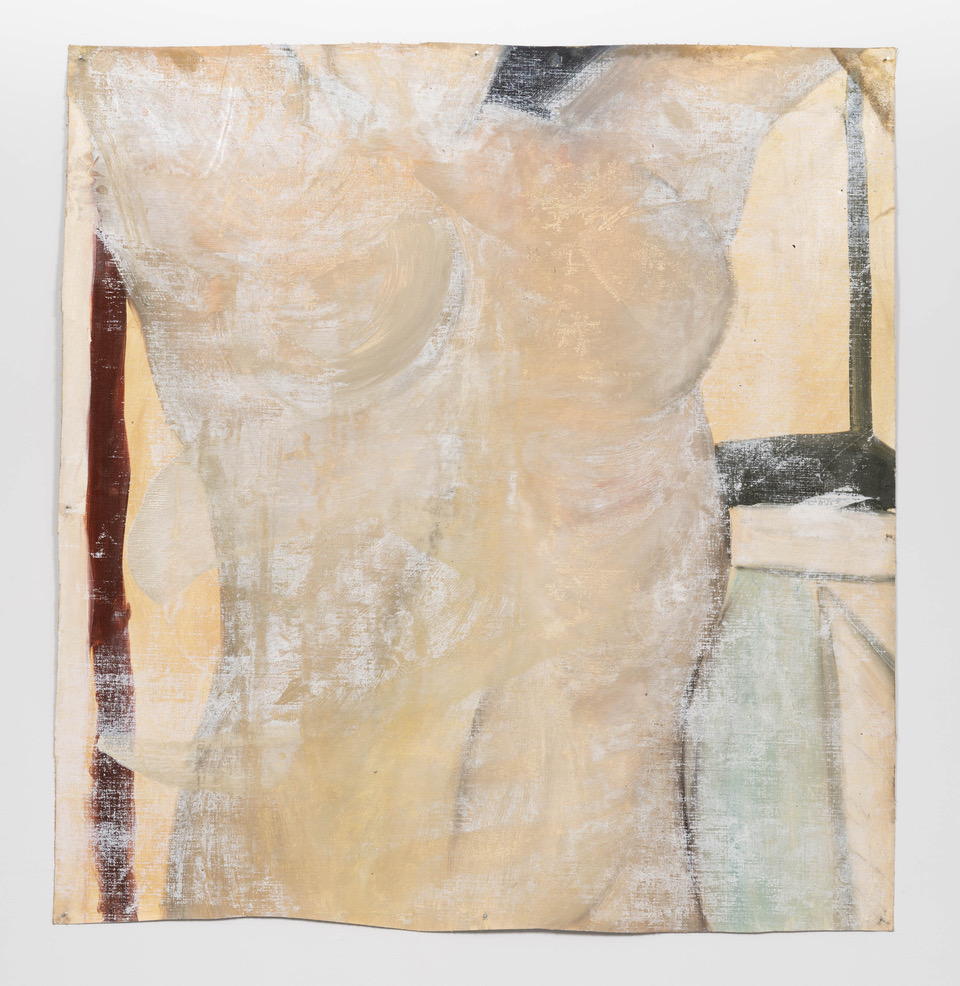

SERPAS: When I really have the space, I treat the figures in my paintings and the paintings themselves like trash. A lot of questions come up: why are you fucking up this picture of a not-so-identifiable torso? The bigger painting I did for this show is based on a photo I found online of this trans girl’s botched breast implants, and I read her complaints about it, and it was like yeah, the doctor messed up and she was upset, but the photo stuck out to me. Maybe that’s fucked up, like I’m memorializing this fucked-up experience she had that she eventually got fixed and would rather forget. At the same time it is personal, because I had the same problem with the same kind of surgery.

PENN: But I’ve always wanted to be the one getting the shot. Basically as soon as I could hold a camera, right after my parents would take pictures or a video, I would say, “give it to me!” Always, “let me see, let me see.”

GLYNN: It’s about control. This came up when we were hanging the show, when a minute before the opening Sam switched out one of the photos because of how a subject in a different photo felt about how her image was being, I guess, contextualized. Sam turned to me and said, “Now I understand why you only paint yourself.”

PENN: You can do whatever you want with your own likeness.

GLYNN: Freedom is important, but it has a price.

PENN: In Hannah [Baer]’s press release for our show, there’s a line about how she [the figure in an image] isn’t looking at you, you can stare back if you want. Is the gaze ever mutual?

GLYNN: I like to think so, but I don’t know. I will say that the paintings of me with a direct gaze are the most desired by collectors. They’re all nudes. “Full frontals,” as one gallerist put it. That’s what I mean by the price. People come into the studio when I’m literally just painting in jeans and an apron and ask if it’s a “performance.” I guess it’s funny how when you’re trans, you can’t touch anything without it being perceived as a prop. But it’s also a fun thing to lean into, sometimes. There is an element of performance when you’re posing for a self-portrait that you’ll paint.

SERPAS: My thinking has changed over time, or with more self-acceptance. I think a lot of people like me went through a phase of wanting to be stealth, which we got through by getting to know ourselves, our appearances, our tastes, or—for those of us who are artists—our respective works and mediums.

GLYNN: Sam, why didn’t you include the self-portrait you printed, the close-up of your face? I thought that one should have been the central photo, or even the only photo and it would have been perfect.

PENN: Maybe that’s why I wanted the photo of my sister to be in the middle, as a proxy for my self-portrait. I didn’t think I could literally center myself in that way, especially not my first time showing. Also, like Ser, I’ve modeled and had my image represented in ways completely beyond my control, so it’s freeing to create something that has value without it being attached to my appearance.

GLYNN: The logic of owning your own body is tied to the whole concept of private property. It’s actually something I think about often, when I’m selling my image. That someone then owns a part of me. Although I’ve always wanted to belong to another person, romantically, I’ve always needed to be free and autonomous. Contradictory, I suppose. But even phrases like “own your own body” only mean something in relation to owning someone else.

SERPAS: I look at nasty images all day. Botched plastic surgery jobs, gross nudes from randos online, stuff that’s maybe too shocking to talk about. Then I process the image and I paint it and by the time it’s on the wall it looks nice. I’m not trying to make it nice, I just don’t have the hand yet to make it look as fucked up and crazy as it is. Everything comes out smoothed and kind of sensual. There’s very few painters who could make something look actually grotesque.

GLYNN: Sometimes I can see myself as grotesque. I suppose the wish in my paintings is that I could be seen as valuable or desirable or, you know, dare I say—beautiful. The way I wish I looked how I look in a Sam Penn photograph…

PENN: But you do, to me you do. That’s the point.

SERPAS: I never show a painting on its own because I don’t trust the single image, or I’m only comfortable doing accumulation. I think about my paintings as vignettes, or as parts of a progressing feeling, like a storyboard for a film. Weirdly, almost accidentally, there’s a similar gesture in both of my paintings in this show, a kind of upward thrust. Two different torsos, both being dragged up through the corner, out of the frame. Nash’s and Sam’s images are stiller or more fully resolved. Mine are glitchy, like a giphy, kind of retarded in their speed.

GLYNN: When Johanna Fateman came to the show, the first thing she said was “skin.” It’s a lot of skin.

PENN: Then in her piece she said the works were disparate.

GLYNN: Are they supposed to be similar? I think our images all relate to each because we relate to each other. Maybe it is that simple.

PENN: It’s not [that simple]. There was a moment before the show when I wanted to intersperse my photos with the paintings, because I was worried that for the viewers facing each of the walls, the show wouldn’t feel cohesive. But the gallery is such an intimate space, it almost forces relationships. Ser’s face is in one of my photos, and Nash’s painting of the rose was about me, or of me, or something…

GLYNN: That painting is actually two roses.

PENN: Who’s the other rose?!

GLYNN: Actually, I’ve decided the roses are just roses.

PENN: Why, because I’m being annoying?

GLYNN: Or because we’re allowed to change our minds. I like that I can change my mind so easily because acrylic dries so fast. I like that every stroke I ever make is there, somewhere underneath. In a certain light you can see every time I made a decision or changed my mind. That’s what painting is, all surface and all depth at the same time. I’m trying to play with that tension.

SERPAS: I only use oil paint—linseed oil. It’s a little less toxic. I mean, I’m not drinking it. I recently started wearing gloves, but I didn’t for a long time. There’s so many ways to fuck yourself up with art. It feels endurance-based.

PENN: Nash, you were working on your paintings until the moment of the show, refining refining refining.

GLYNN: I’m a perfectionist, but I consistently fail. Which I suppose is part of my charm.

SERPAS: I would call myself an obsessive. I end up building paintings around huge mistakes.

GLYNN: Mistakes are crucial. Every mistake has led me to a finished painting, so the whole process of painting feels like self-correction. In the painting of the roses on the table, you can see that there was one line cutting across the whole plane, because I had extended the horizontal line of the tabletop so it doubled as a horizon line, and then I changed my mind. I needed to show the corner of the table in this kind of shallow focus that gives you the feeling of deep space, with the lines being sharpest near the focal point—the vase, the corner—and then fading out toward the edges of the canvas. This way it looks like the vase could fall.

PENN: In the photo of Sarah and Hannah, you can see a sliver of my finger in the frame, which wasn’t intentional. I left it in because it makes sense for it to be there, maybe it even makes the photo more narrative in that it’s obvious how quickly I grabbed the camera, how the people in the photo were already posed like that naturally. But I like it better than the ones that are technically better, the ones that look more like my other photos, because by the time I turned on the flash, the moment had changed.

GLYNN: Particles turning into waves, like in that experiment you love, what’s it called?

PENN: Double-slit experiment. It’s the one where these physicists found that observing particles of light changes how they behave, specifically whether they act like particles or waves. I think about it all the time. People always act a little bit differently when I look at them through the lens of the camera, even when they’re not looking back.

GLYNN: I wonder whether my paintings can make people perceive me differently, which is maybe the same thing or maybe the opposite of what you’re saying. I try to rearrange people’s perceptions. Every painter does. There’s all these tricks of the trade, like how the rectangle on the horizon draws people toward the horizon line, obviously, and then the eye comes back to the foreground, where I put another almost meaningless shape, a circle. If I had to explain why a circle and a rectangle, I would say that the inclusion of these sort of camouflaged shapes in the landscape is a kind of protest against symbolism, or against the syntax of the phallus, whatever.

SERPAS: Nash, do you feel like me, like when you’re painting you’re fighting against a painting?

GLYNN: I wouldn’t call it a fight so much as a dance.

SERPAS: I like that. I want the dance.