The unknown history of platform shoes

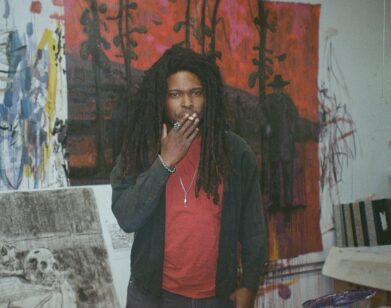

IMAGE COURTESY OF BALENCIAGA.

Towering shoes, so high they threaten to break an ankle, are closely associated with the late ‘90s, when Spice World was still a box office boon. Platforms, whether they are bejeweled sandals or perspex boots, actually go back a lot further. It’s an item that has transcended trend and earned its place in the annals of fashion—an ancient garment that’s been valued as both fashionable and functional, despite its apparent danger to the wearer.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York’s “Items: Is Fashion Modern?” exhibition explores sky-high footwear alongside 111 other items of clothing and accessories that have had a strong, global impact in the 20th and 21st centuries. “Items” takes an encyclopedic, alphabetical approach to pieces including Air Force 1 sneakers, Burkinis, Door-Knocker Earrings, Kilts, Spanx, Tracksuits, and Yoga Pants.

Most recently, Balenciaga’s SS18 show in Paris included decorated four-inch crocs. “The platform shoe is so prevalent across geographies, time periods, and styles,” says Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator in MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design. “It was impossible not to include it as a typology. Garments and accessories change our shape, at times in ways that offer us power and freedom, and at others, in ways that compromise our autonomy or make us conform more closely to particular standards. Platform shoes can transform their wearers’ stature and make them more imposing—or they can almost hobble their wearers, much like stilettos, profoundly altering body posture and appearance.”

The platforms on show have been curated and presented chronologically from the 1930s to the present, getting larger and taller through time. Included are platforms by Delman, Vivienne Westwood, and Alexander McQueen, and stage platforms owned by Elton John.

“We tried to show the ways in which platforms have been a regular part of fashion’s lexicon, but also changed rapidly and often,” adds Antonelli. “It’s much like the Little Black Dress, which has retained its color but changed its silhouette over the decades. The platform shoe is similarly chameleonic.”

The history of the platform begins around 600 BCE; the Greeks used them in plays, to increase the height of characters. High-status women also wore them. During the Middle Ages, the Venetians’ platforms were called Chopines, while much of the rest of Europe’s platforms were called Pattens. Both Chopines and Pattens were worn to avoid wet, rainy streets. These platforms had thick, wooden soles and various forms of leather strapping, ensuring both height and relative stability, and often high social standing.

In use until the early 20th century, Pattens typically held in another shoe and were sported by both men and women. There are tales of their ostentatiousness leading some English Christian churches to forbid their priests to wear them. Alternately, Spanish rabbis of this era attributed wisdom to those who wore Pattens on Shabbat. In the 15th century, the Spaniards had allocated the majority of their cork resources to the soles of their own, more conical version of the Chopine. These, as well as those worn by the Venetians, often required the help of two servants to put on and assist the wearer in walking. Venetian women, in particular, are credited with Chopines that, during the 16th century, provided as much as 20 inches of extra height—a signal of wealth that allowed for lengthier skirts.

During this era, the platform’s sex appeal had already been well-established through use by high-class prostitutes. In Europe, they were worn by courtesans, providing an extravagant, alluring tilt for attracting customers; in Japan, they were first called Geta—a more flip-flop-like platform, with soles like teeth—worn by geishas to protect their expensive kimonos from mud. The Chinese called their version of this dainty, feminine shoe a Qixie, which introduced a separate heel from the thick platform on the forefoot and sometimes included embroidery on the upper.

The platform’s history in fashion began incubating in the United States, United Kingdom, and Europe from 1930-1950. Actress Marlene Dietrich had a pair designed for her in the early 1930s by Moshe (Morris) Kimel, a Jewish designer who escaped Berlin and opened his Kimel shoe factory in Los Angeles. A French footwear designer named Roger Vivier sketched a platform sandal in 1937, which Elsa Schiaparelli used in one of her collections. By the time wealthy Beverly Hills women caught on, Salvatore Ferragamo introduced The Rainbow, a platform sandal designed for American entertainer, Judy Garland, inspired by her singing “Over The Rainbow” in The Wizard of Oz. Ferragamo notably used layers of wood and cork instead of leather, an experimentation born from the effects of WWII wartime rationing.

The ’60s to ’80s brought the platform—the visual antithesis of the ’50s favorite, the stiletto—to its peak, thanks in large part to the music of this era and trendsetting boutiques like London’s Biba. Young men and women wore them to the disco, and they were dually embraced by a range of rock musicians, like Gene Simmons, David Bowie, Stevie Nicks, and Elton John, and funk musicians like George Clinton. They were worn by fans of punk, ska, rockabilly, and heavy metal, often in the creeper style sold by Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood early on, or metal-decorated, heavy black boots. In general, the platform expanded to styles that also included sneakers and espadrilles.

In the early ’90s, Vivienne Westwood brought the platform back into high fashion; one shoe in particular, the Super Elevated Gillie, paired a five-inch platform with nine-inch heels that Naomi Campbell was wearing when she fell on the runway in 1993. By the late ’90s, the Spice Girls were making platform shoes fly off of store shelves, they were a staple of Marilyn Manson’s look, and ravers and club kids had popularized multi-colored platforms.

In the 2000s, platforms were a signature garment for popstar Lady Gaga, and included designer Noritaka Tatehana’s famously heel-less 2013 Lady Bloom platforms. Gaga also wore (and owns) a rare pair of Alexander McQueen’s Armadillo boots, which were made from hand-carved wood, originally only for the runway.

“Platforms are, as a typology, in constant tension between timelessness and temporality,” concludes Antonelli, summing up the shoe’s global, manifold adoptions and interpretations.

“For me, this is what modernity is all about.”

“ITEMS: IS FASHION MODERN?” IS ON VIEW AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART UNTIL JANUARY 28, 2018.