ART

The Georgian Artist Andro Wekua Considers Conflict on the Canvas

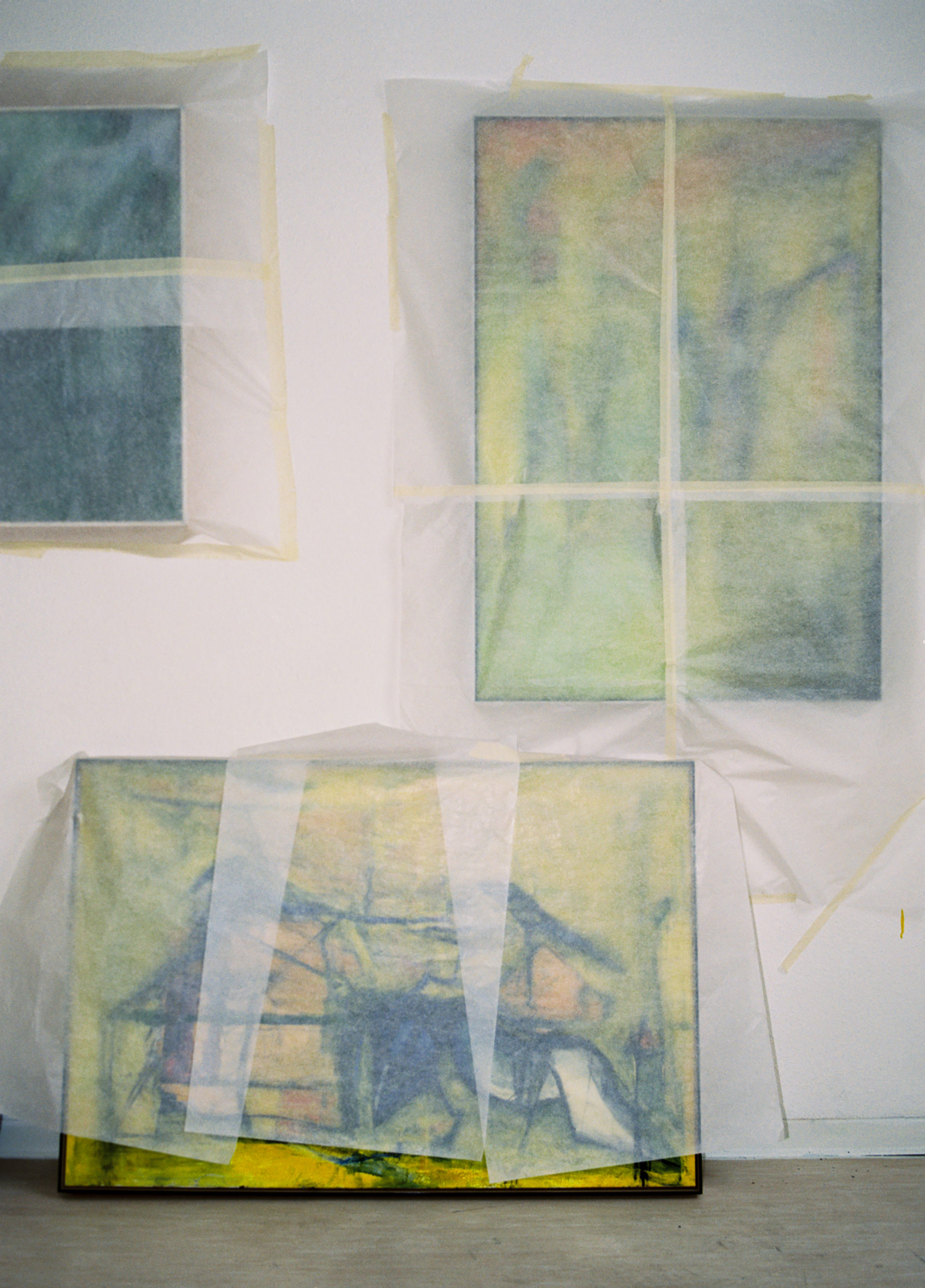

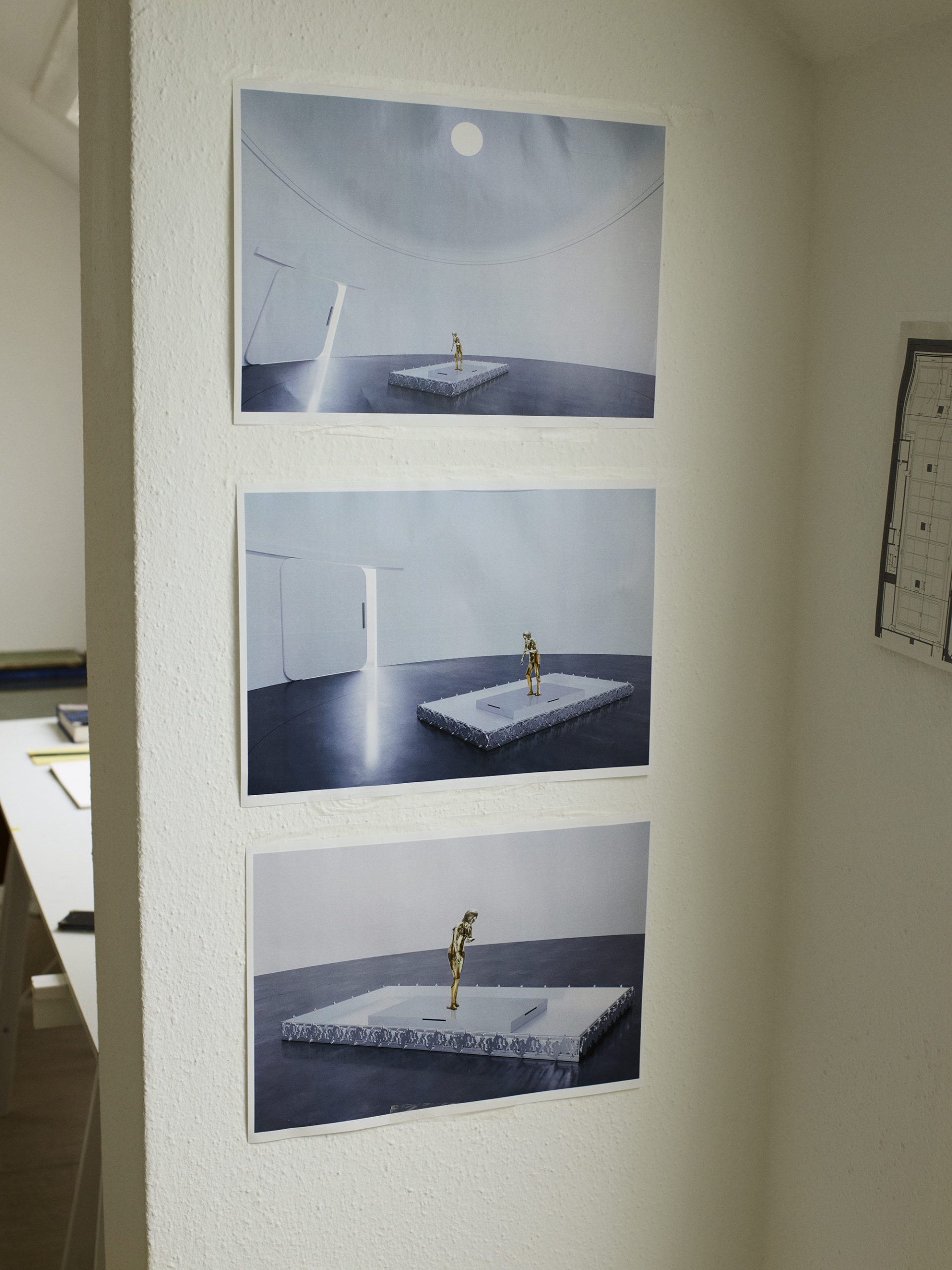

Like dreams, Andro Wekua’s mixed-media paintings seem created out of complex layers of the deeply personal and the vastly mythic. And like the best art, the work feels both of its time (a lost generation on the brink of another world war, circa AD 2022) and utterly, almost biblically timeless. The 44-year-old artist grew up in the Georgian state of Abkhazia on the Black Sea, his family fleeing when he was 15 to the country’s capital, Tbilisi, after the region fell to Russian forces. Wekua now lives and works primarily in Berlin, but the memories of his childhood continue to haunt his mind and inform his art (to this day, Georgians are not allowed to return to this Russian-occupied territory). This fall, Wekua presents a series of new paintings at Gladstone Gallery in New York that evoke these lost visions—more retrievable in the imagination than they can be in a geopolitical red zone. To mark this touchdown in Manhattan, the artist spoke with his friend and fellow painter Elizabeth Peyton. Spoiler alert: St. George slays the dragon.

———

ELIZABETH PEYTON: Where are you?

ANDRO WEKUA: I’m in Tbilisi, flying back to Berlin tomorrow. Where are you?

PEYTON: I’m in my studio at home in New York.

WEKUA: I can see there’s a skylight. How’s New York?

PEYTON: New York is not empty. It’s nice and lively, but so hot.

WEKUA: I like your haircut.

PEYTON: Thank you. I didn’t have time to wash my hair. Yesterday I went up to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I hadn’t been there in five months, and it was like going into nature for the first time. It’s just so great. It’s nice to be in a city near all of that work.

WEKUA: It is really important. Here there are a lot of old churches with Byzantine frescoes and icons, which are inspiring to me in terms of painting. Growing up in Soviet times, it was difficult to have access to contemporary art. I just went to the Samegrelo region in Georgia. There is a church, which is from the 10th century, and it has frescoes inside from the 14th century. There was one of St. George with the dragon. But how I saw it, he wasn’t wielding a weapon like he’s usually shown. Maybe that part has been erased over time. There was no slaying, which was really beautiful. The dragon was knotted within itself. I never saw anything like it before.

PEYTON: I’m thinking of that Raphael painting of St. George, capturing the moment before he kills the dragon. It’s a small painting and it’s violent, but it’s also sweet. Do you know it? It’s got some really good armor in it.

WEKUA: I’ll have to look that up today.

PEYTON: Are you feeling close to the war there? Is that part of daily life?

WEKUA: It’s not far from the region where I’m from, which is on the Black Sea in Georgia. Ukraine is part of that region, so you do feel much closer to it and more insecure than in Europe, definitely. People are scared and more careful. There are a lot of Ukrainians here and a lot of Russians who left their country, so it’s much closer to the situation. But it doesn’t feel dangerous. What can you do? I don’t know.

PEYTON: Do you feel like the war affects your work?

WEKUA: It definitely affects my emotions, every day, and I don’t think that’s too separated from my work. It’s difficult. It’s a personal thing. I myself experienced it in my childhood, in the early ’90s. In Georgia we had a similar situation with Russia supporting an ethnic war, although it was not on the same scale as it is in Ukraine now. My family had to flee their region, and since then we haven’t been able to go back.

PEYTON: Maybe the work you make speaks to all the tragedy. I often think about what you once said to me: “The most radical thing you can do is be in your studio and paint flowers.” I was looking at this Louise Bourgeois painting yesterday. It was this beautiful abstract painting of a purple blobby flower, and I noticed the year, it was 1944. It was during the war. And I just thought how beautiful that was, that she was in her studio. I think that maybe there was a lot more going on emphatically in that weird blobby flower.

WEKUA: I totally know what you mean.

PEYTON: I was looking at some paintings of yours from your last show in Berlin. There is an abstract painting of a rose. It’s so beautiful.

WEKUA: You know, I wanted to do a flower show in New York. Then this war started, and I couldn’t do it. The faces start coming back into the work, but a face in an abstract way. I did find a balance with a few flowers.

PEYTON: You have to let the work become what it becomes. And flowers and faces are not so different.

WEKUA: That is true.

PEYTON: Do you just let the face emerge or does it start from a particular person?

WEKUA: Most of the time, I let them emerge. There are some that are more personal, faces I know or feel that I know. And sometimes I do start with people I know, too. Often I don’t know how to paint them and that’s when it becomes interesting.

PEYTON: A long time ago, I was painting Freud, and I was like, “Oh my god, this looks so much like my father.” But it seemed right so I let it happen. It’s funny how stuff like that can happen. If I’m painting something from the opera, where I’m not certain how that person’s face looks, it’ll start looking like somebody I might be thinking about, or having trouble with.

WEKUA: Today I was looking at people’s eyes, and thinking how beautiful they were. But then there’s the mouth, and I was thinking how weird mouths are and I realized that I’m scared to paint mouths. Most of the time I give everything over to the eyes. But people do show a lot with their mouths. The tension in the way they hold their lips gives a lot away.

PEYTON: A millimeter one way or another on a mouth is a completely different expression.

WEKUA: Yeah, maybe even more so than the eyes. But even the muscles of the face. It’s all telling for a painter.

PEYTON: It’s true. I think people get very focused on the eyes.

WEKUA: I promise you, after we talk, go look at photos of mouths without eyes. It will surprise you.

PEYTON: It’s hard to look at both the eyes and the mouth at the same time. You usually have to choose. Maybe when you’re painting you can, because you have a distance. But if you’re having a conversation, it’s hard to take both in.

WEKUA: It’s not possible. You just go up and down, and you just see how it’s not one. It’s disarming.

PEYTON: Outside of painting, what are you doing to keep yourself together these days?

WEKUA: It’s really difficult to stay in one place for me these days. I feel, not anxious, but like everything and everyone is more fragile than a few years ago. I’ve just been enjoying being in my garden here. Tomorrow I will go back to Berlin and try to paint.

PEYTON: Is there anything else I should ask you? Anything you want to bring up?

WEKUA: I don’t want to miss my flight tomorrow morning.

PEYTON: That’s important information. [Laughs]

———

Photography Assistants: Abdelrahman Darwish and Jelka Von Langen

Fashion Assistant: Camille Pailler