art!

The Artist Joe Mama-Nitzberg Is Putting His Private Universe on Display

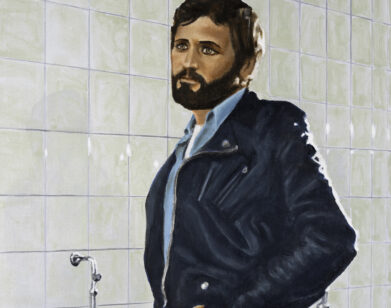

Photo by Smith Galtney.

“The best work of art is one that tricks you,” says the artist Joe Mama-Nitzberg on a recent Friday afternoon. He’s speaking generally, but these are words that the Catskill, New York-based artist lives by. The ‘trick’ at play in Mama-Nitzberg’s work is rooted in his mastery— and subversion— of semiotics. Messaging from the realms of the erotic, the commercial, and the historical don’t so much ripple under the surface of his collage-like works as rip through them, confronting the viewer with a collision of references that often take time, and insight, to parse. A single Mama-Nitzberg piece unfolds to reveal imagery borrowed from discontinued magazines and the artist’s own backyard, layered with playful Pop graphics and cryptic quotes from modernist authors and queer theorists. Each augmentation adds a new and unnerving dimension to the artist’s work, although not necessarily one he expects will land with viewers. “I don’t expect people to get all of that,” he says of the hyper-personal references built into Classes in Optical Art, the artist’s solo exhibition opening tomorrow at the Grant Wahlquist Gallery in Portland Maine, “But my hope is that they resonate on this background level.” To mark the exhibition, Mama-Nitzberg spoke with his friend, the photographer Jack Pierson, about everything from their glory days at the Chateau Marmont to the translation of personal history into a universal medium.

———

JOE MAMA-NITZBERG: Hi Jack. Where are you?

JACK PIERSON: I’m on the Long Island expressway going out to Long Island.

MAMA-NITZBERG: Oh my god, is it flooded still?

PIERSON: It looks like it definitely was. Lots of abandoned cars on the side of the road. So, let’s begin. How did we meet?

MAMA-NITZBERG: I was in graduate school at Art Center in the early ’90s, and you gave a talk for a course that I was TAing. You didn’t have a car, I had to come pick you up from your hotel. This was one of my favorite things ever. I said, “I can pick you up. Where are you staying?” And you said, “Chateau Marmont. Heard of it?” I sassed you right back and said, “Oh really? Which bungalow? ” And you said, “I’m in a room in the main hotel.” I said, “Oh, too bad.” That’s where we started.

PIERSON: Exactly. Speaking of the Chateau, I remember curating a room for Regen Projects at the first Chateau Marmont Art Fair, and I recall including a piece of yours that I think was called “Stonewall Speedball.”

MAMA-NITZBERG: I am still very honored by that. It’s a self-portrait of me as Judy Garland in the snowy poppy field from Wizard of Oz, and it was hung under a painting by John Wayne Gacy.

PIERSON: How did you make that backdrop? Was it Photoshop?

MAMA-NITZBERG: It’s pre-digital. I mean, that stuff was way beyond me. My friend took the photo for me, and we built the set with crepe paper flowers from the Dollar Store. The snow was laundry detergent.

PIERSON: Lo fi. Fantastic.

MAMA-NITZBERG: Very ’90s. My vision was for it to look like Pierre et Gilles, if they didn’t have any money. In the art world in 1994, Pierre et Gilles were the least appropriate reference you could make. I wanted to push back on the expectations.

PIERSON: Did you go to art school for your undergraduate degree?

MAMA-NITZBERG: I have a film studies degree, which means I can watch a movie professionally. Shockingly, there’s not a lot of work in that.

PIERSON: Wow. So, was the Judy Garland piece, focused more on self-portraiture, or is it more of a cultural critique?

MAMA-NITZBERG: Both. At the time, Judy hadn’t yet been reconsidered as this empowered queer icon. She was still either the old queen or the tragic embarrassment.

PIERSON: How do you feel that has changed? Is referencing her empowering these days?

MAMA-NITZBERG: I think when a lot of pre-digital culture migrated online, it was reorganized through a contemporary lens. There is still the big mess, scandal mongering Judy, but more and more, especially with the Renee Zellweger biopic and the “gay history” Instagram feeds, the tone is more sympathetic—which I appreciate— but also a little watered down.

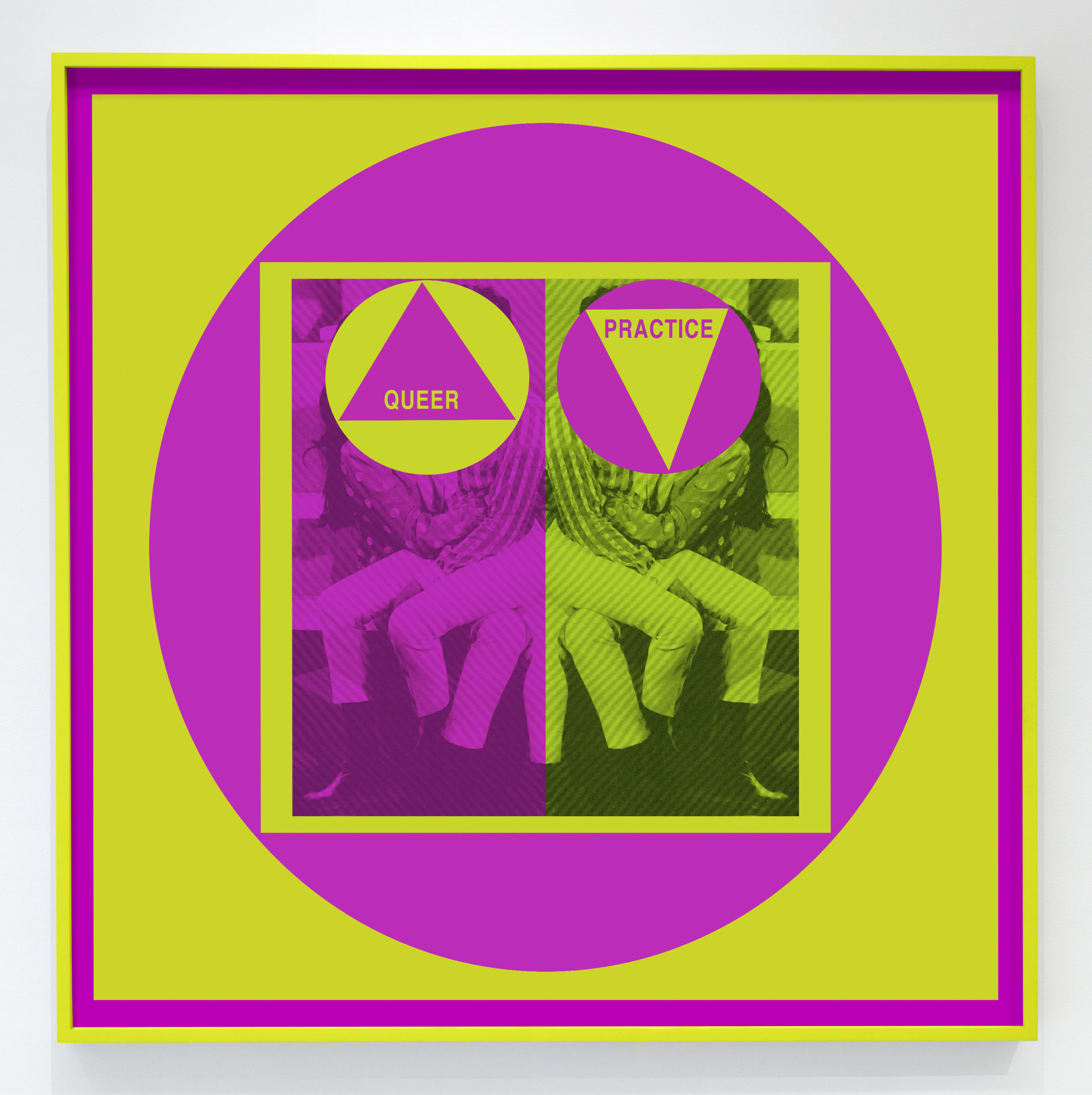

- “Queer Theory,” 2021 | Archival inkjet print in custom painted frame 31.25 x 25 inches.

- “Queer Practice,” 2021 | Archival inkjet print in custom painted frame 30 x 30 inches.

PIERSON: Not to sound really old, I just feel like the generation I find myself lecturing these days is not eager to listen. They’re more like, “Okay, we’ll listen to you until you shut up about this.”

MAMA-NITZBERG: I’m not sure it’s their fault. I just think the internet makes you feel like you know the whole story.

PIERSON: Or that you have a community. I’m not blaming anybody.

MAMA-NITZBERG: That’s one thing I’m playing with in my work. I want to use these very dated references that are still powerful, and hide them or foreground them while bringing in a little bit of internet culture, so it’s like, “granny makes a meme.” My hope is that they resonate on this background level, where they communicate something to people who don’t necessarily get the references.

PIERSON: Your new work is very graphic and kinetic. But I just wonder, art you preaching to the nursing home, somehow?

MAMA-NITZBERG: Perhaps. No. My hope is that these references bounce back and forth between each other, in a chicken-or-egg way. I involve these cultural figures, like Judy that we so identify with, and situate myself in her space. So, I am this being who was impacted by Judy, but when I photograph myself in the poppy field, it’s like, “Yeah, that’s just some queen laying in a poppy field.” I don’t become a historical figure.

PIERSON: Right.

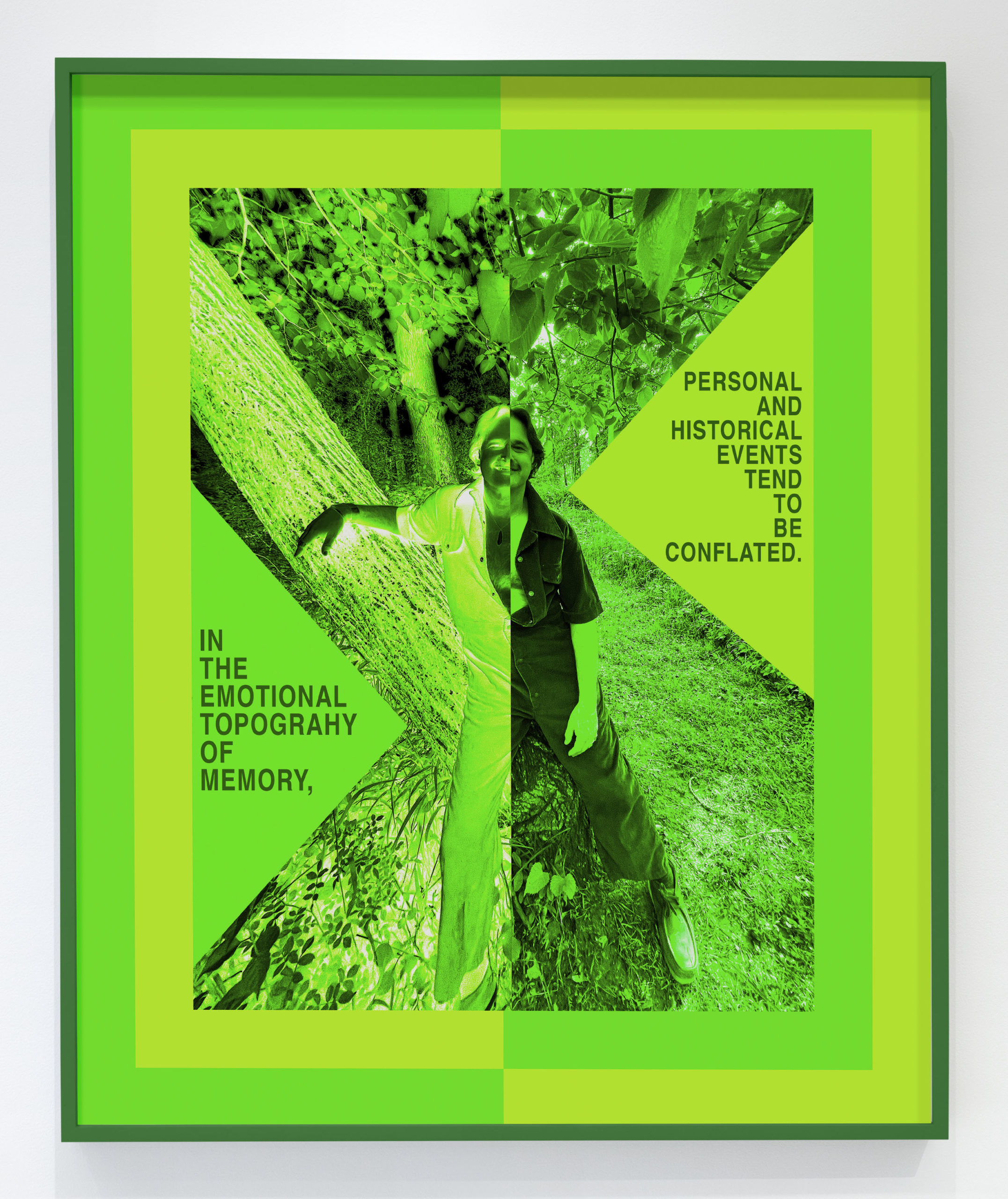

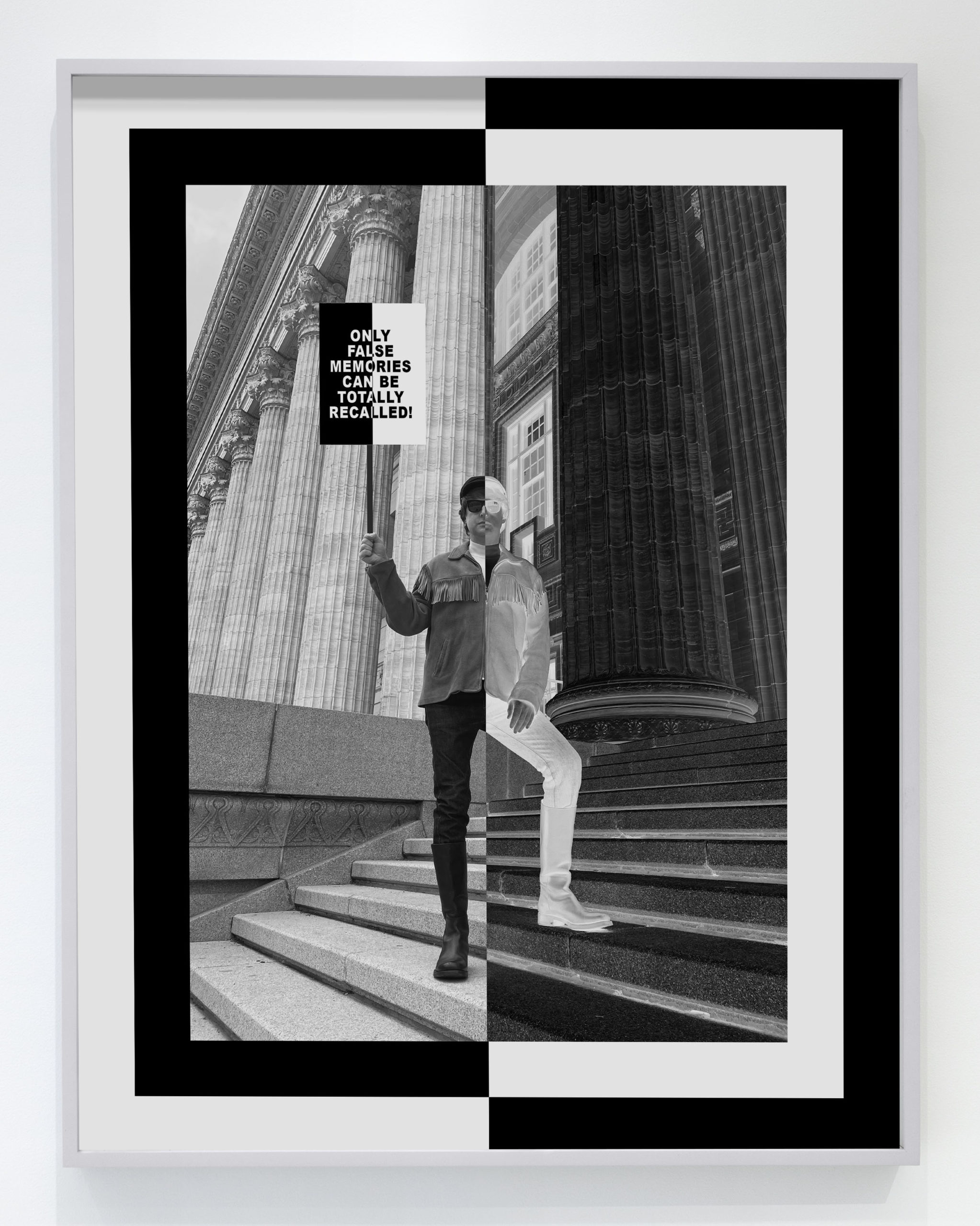

- “Emotional/Personal/Historical (Self – Portrait Mid – 70s ),” 2021 Archival inkjet print in custom painted frame | 13.5 x 11 inches.

- “Total Recall (Self – Portrait Late 60s),” 2021 | Archival inkjet print in custom painted frame 14.5 x 11 inches.

MAMA-NITZBERG: Take the pieces with the Svetlana Boym quotes in the new show. One image is the Education Building in Albany, and the other one is in our backyard in Catskill. It’s supposed to be the same person, seven years later, as they came into their full gay male identity, trying to be sexy in that crazy jumpsuit that is just so cringe. The base image is from After Dark Magazine, which ran from ’68 to ’83— so literally the year before Stonewall and early AIDS. It’s a rich source for me because it’s that golden age of gay pride and sexual revolution. So many of the guys in the magazine were cabaret pianists or models in these fashion shoots or dancers or actors who were so celebrated at the time, and who you just assume were AIDS casualties. It makes you ask, what would this culture look like if AIDS never happened? For someone the age I am with the life I’ve led, I know you can identify with this, the AIDS lens is inescapable.

PIERSON: Is that what “They Had Had” is focused on?

MAMA-NITZBERG: Yes. It’s a fashion story from After Dark for ‘70s underwear and swimwear that I’ve altered and doubled and reversed. The text is a Henry James quote from The Golden Bowl that reads, “They had had fears just as they had had joys.” I flipped it, because I wanted to give these guys their joys before their fears. I don’t expect people to get all of that, but I hope it resonates with the tone of loss and of that journey.

“They had had,” 2021 | Archival inkjet print in custom painted frame 24 x 34 inches.

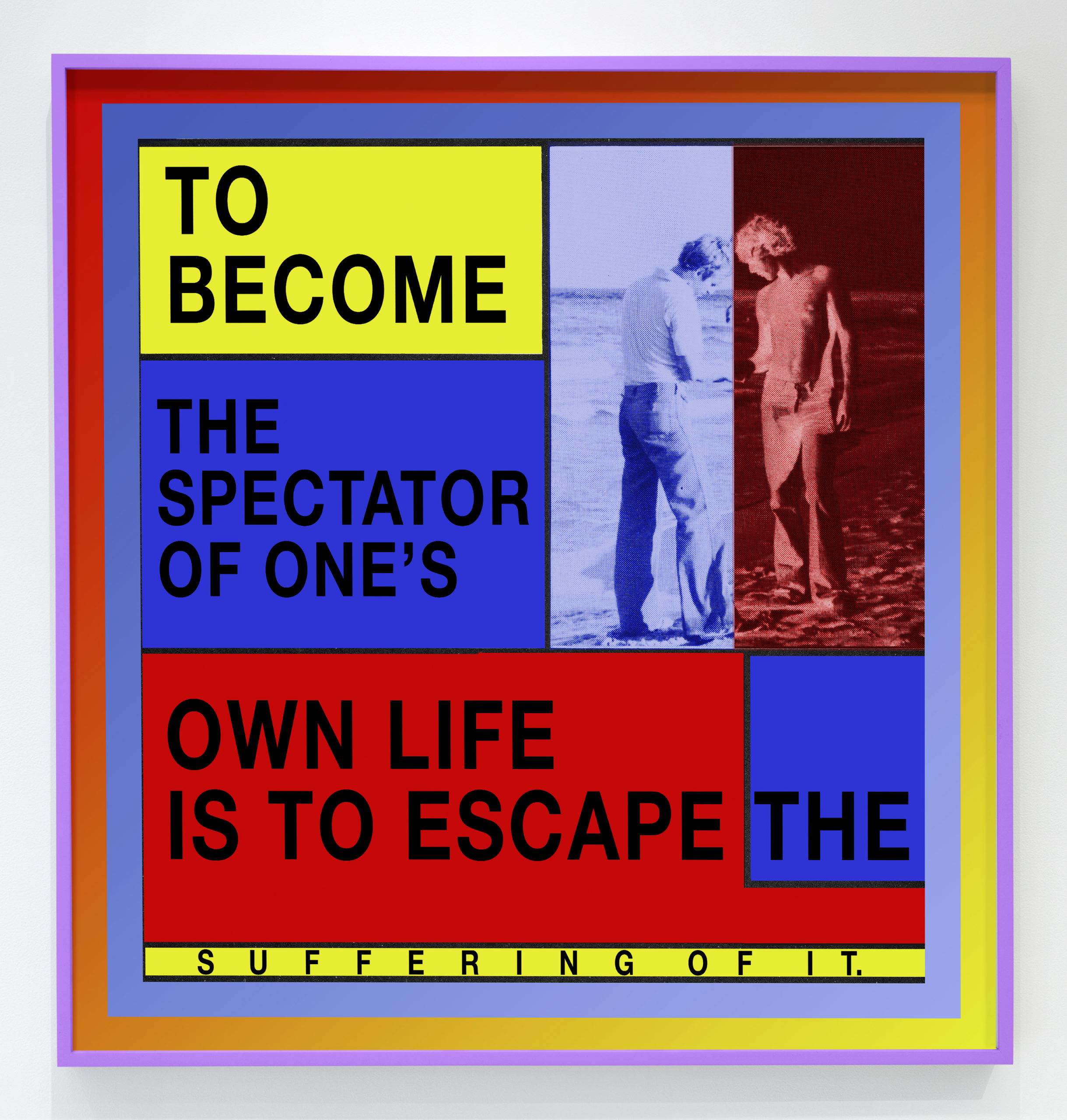

PIERSON: Do you do these things to become a spectator of your own life, to escape the suffering of it?

MAMA-NITZBERG: I think it’s a coping mechanism, a grieving process, a way to make sense out of things that are unfathomable. It’s a way to formalize that vulnerability. I don’t expect a viewer to recognize every nuance of this work and intuit what it means to me, but maybe it resonates for them in a different way. I can only make work for me. That’s the only way to be universal, is to make it work that’s incredibly specific. You do that very well. You’ve always used your emotional vulnerability in a very public way.

PIERSON: Definitely. It’s a way to tell your story that’s different than regular art making. I don’t think many conceptual artists care as much about the story or the self as you and I do. I feel like other artists can get all that vulnerability and narrative just by pushing paint around. So why do they need to build in all of this reference work?

“To Become,” 2021 | Archival inkjet print in custom painted frame 28 x 26.3 inches

MAMA-NITZBERG: That’s interesting. We have all these expectations of how different mediums perform culturally. To me, the best work of art is the one that tricks you, where you approach it thinking, “Oh, it’s this,” and then you realize it’s not that at all. That prompts further exploration. So, I hope to seduce on one level and then, through the back door, bring in these other elements that defy expectations. To me, that is the magic dust. I hate when my expectations are met by art. Other people don’t feel that way, and that’s fine, but I’m hoping to reach that audience that does get a charge out of that feeling.

PIERSON: Well, let’s hope they come storming through the door at the Grant Wahlquist gallery.

MAMA-NITZBERG: And let’s hope they come storming through the door at Regen Projects. We’re taking the coasts by storm, from Maine to California.