IN CONVERSATION

Terence Nance Introduces Solange to His Imaginary Friend

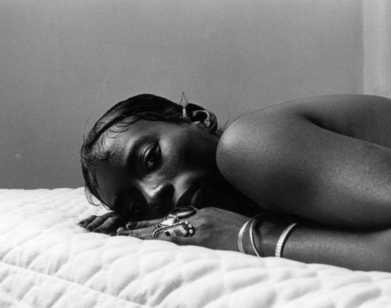

Years ago, Terence Nance and Solange Knowles were slated to star in an Afrofuturist film by Barry Jenkins called Wonderland, where they’d play a married couple shot back into the past by a time-travel machine powered exclusively by Stevie Wonder songs. When the two got together last month in Philadelphia, where Nance is about to debut his first-ever solo exhibition Swarm at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania, Solange wondered how different their lives might be had the film come to pass. “My feeling,” Nance said, “is that we would have made the work we ended up making.” A fitting answer, given how much of Nance’s expansive and multi-disciplinary oeuvre feels powered by creative instinct and destiny. The artist and filmmaker, who grew up not far from Solange in Dallas, Texas, has now collected several of his surrealist experiments in film and sound—including his short film Swimming in Your Skin Again and his HBO series Random Acts of Flyness—in an immersive show co-organized by BlackStar Projects and curated by Maori Karmael Holmes. Before the opening of Swarm, on March 10th, Nance met up with his old friend and would-be co-star to shoot some film photography and talk spirituality, gentrification and their Texas origins. Then, they introduced one another to their respective imaginary friends, or “sentient wounds,” as Nance likes to call it.

———

SOLANGE KNOWLES: So you and I met after we were cast as the two leads in a Barry Jenkins film about a Stevie Wonder time machine. You’re so brilliant at creating alternative parallels and realities and dimensions. How different do you think the trajectory of our lives would be if this film had seen the light of day?

TERENCE NANCE: Oh my god. That’s such an interesting question. As you were saying that, I was like, that’s how we met?

KNOWLES: Yes! Literally. They had arranged for us to meet for like, a chemistry test. And then we just reached out to one another like, let’s meet up.

NANCE: Oh, yeah. That’s why we met. Wow. Okay. Well, how would our life be different? Our trajectories?

KNOWLES: I think it would be very different for me.

NANCE: Well, why do you think so?

KNOWLES: I guess, because of my relationship to acting. That just feels like a part of myself and a muscle that I haven’t really exercised in so long. And so I’m curious, what it would have or would not have done for my music mind. Like, what if we would have just been actors?

NANCE: My feeling is the opposite. My feeling is that we would have made the work we ended up making. And then collaborating on the things we ended up collaborating on. It would have been more or less the same. Now that I’m remembering it, what that script represented was the possibility of connecting to Stevie. [I think about] what playing those characters would have brought out of us in terms of study, you know? It would have just been a more public channeling of who we are when we work together.

KNOWLES: I can see that.

NANCE: You know, the glassware line woulda still been poppin’, and When I Get Home would have still happened, and A Seat at the Table would have still happened, and all of your music and all of your films, and I think all of my music and all of my films would have more or less been supported by a Barry Jenkins film that understood who we were. Which is kind of crazy to think about in terms of who he is and what he has become since then cause, you know this is pre-Moonlight. You know what I mean? I don’t know, but maybe we can still do it! We gotta hit ‘em up!

KNOWLES: I’d be down, I’d be down. Okay, so we’re also both from Texas. You spent quite a lot of time in my native neighborhood. I was so honored that you directed a piece in my film for when I get home. I would like to know how your Texas roots inform your work.

NANCE: Well, one, thank you for having me, because your embrace of your neighborhood was just so necessary for me in terms of my own embrace of my own neighborhood. And for those that don’t know, that was shot in your neighborhood [in Dallas], but also on the street I lived on, on Binz street, is where the house I lived in briefly was. So it was a portal in that way. My dad took me to one of his friends in Lancaster, Texas who had horses, and you learn how to ride and, you know, he put me on a young horse. And that horse took off and I was crying. And he rode up, calmed the horse down and was like, “Are you chilled out now? Alright, keep going.” I don’t think an experience like that is necessarily translatable to what I’ve made visually, you know what I mean? But I do think these types of initiations are in what I make, you know? Sometimes more directly, sometimes more obscured.

KNOWLES: Yeah. Even in the “Dreams” [Solange’s Nance-directed music video] piece, the way that you’ve interacted with nature in that piece was especially a repeated theme in your work.

NANCE: Exactly. I remember growing up in Dallas, feeling like you could drive 15 minutes in any direction and it was just fields. I think it set my vibration towards needing a certain type of landscape, undeveloped by urban sprawl. I needed to see how God was working. Because that’s just where my consciousness was set. I grew up in State Thomas, which is right north of Dallas. At that time, that was a Black neighborhood. But my mother said that they tore down I think 30 houses in 30 days when I was like, five years old. So it was becoming an open field as I was growing up.

KNOWLES: Why did they tear them down?

NANCE: It was one of the oldest Black neighborhoods, to my knowledge. So they were trying to buy them up or designate them as blighted so that they could tear them down and develop the neighborhood they built on top of it, which is called “uptown” now. So that whole project of urban renewal just totally flattened the place that I remember most from my zero to five or six years old. So it had the effect of getting me accustomed to needing open space, you know?

KNOWLES: That makes a lot of sense. The first time I experienced your work was seeing An Oversimplification of Her Beauty. I was blown away by the raw and ripe vulnerability, its ability to cross time journeys and universes so poetically. How do you feel when you revisit that film?

NANCE: I rarely revisit it. But I believe the last time I watched it, I felt deeply proud of that person who made it at the time for really trying to come to some level of self-awareness. I ain’t have no therapist at the time. I had friends to talk to, kind of. So I was like, trying to have a mirror moment, you know what I mean?

KNOWLES: How old were you?

NANCE: I think I was like, 20 when I wrote it. It was a mirror moment that I tricked myself into thinking wasn’t one because I was like, “Oh, I’m making a film,” you know? It’s use was for me to just keep it real with myself. You know what I mean? And then because of that, it feels diaristic in a way that it just isn’t because it’s a movie.

KNOWLES: You also scored that film, and many of your other works, and last year you released your album V O R T E X. What are you settling to achieve through these sonic revolutions that you can’t through filmmaking?

NANCE: There’s so much I can’t do with filmmaking because of what’s beautiful about it, which is that it requires negotiations with all the other people and elements that you need to get a film done. With music or V O R T E X, I can get pretty far with just me. It just feels like a more lubricated channel. There’s less inherent obstructions to negotiate around.

KNOWLES: Absolutely.

NANCE: And I think you know, I’m trying to heal myself, ultimately, with sound.

KNOWLES: Knowing that, your intention to use music to heal, how do you feel about the format of a formal album, because I have my own sort of love-hate relationship with the album format as a tool to release music.

NANCE: Well, I have a lot of reverence for it, because I have been healed by albums personally. Like, I can put D’Angelo’s Voodoo on right now, top to bottom, and just be with it. On technical levels, but more so on spiritual levels. It’s an experience of the unknown that draws me in and just activates my curiosity in a super intense way, even now. There’s just like a thing that happens when you’re in some continuum with your elders, your ancestors. I get an impulse. I want to try that. I want to see if I can make something that useful, you know, to prove it to myself. Yeah, so if you’re thinking about not doing albums, don’t even go there.

KNOWLES: I appreciate your answer. It’s a beautiful reminder of why they exist.

NANCE: I think you really influenced me in this, too. When you played me When I Get Home the first time, you played it in one file. And I was like, “why is it like that?” You were like, “Oh, I edit the whole album like this.” You said something like, “That way, if I’m ever bored I know where I’m bored and to just cut it out.” And I was like ah, so it’s a film. It’s one file. You influenced me in focusing my aspirations.

KNOWLES: Aw, that means a lot. That’s a beautiful reminder. So, I got to see the whole season [of Random Acts of Flyness]. I was talking to Gio [Escobar, Knowles’s partner] about what a necessary and urgent moment this work is to be out in the world, and all of the reflections I see of myself in some of the characters. I specifically want to talk about Celine, the name Najja has for her wounded self. I have one of these on my own, except this is a whole family I called the Pintos.

NANCE: The who?

KNOWLES: The Pintos. When I was a child, I had a whole ass imaginary family that I named the Pintos, which started off as a reflection of all the things I thought a family should be. But then I started to use them as a way to control everything around me to keep me safe. And as an adult, the Pinto’s no longer serve me. They turn me very green and mean, like Celine. So in the therapy scene, when Najja talks about Celine, I kind of just wanted to cut off the show at that moment, lay down and not talk to nobody for a couple hours. I was like, “How dare you go in on us like that?” But I would like to know who’s your very own Celine?

NANCE: Oh, of course. So that’s one of the real parts of the show. Not Celine, necessarily. Mine is Mandy. So I named him Mandy because I like saying, “Shut up, Mandy.” Initially, my relationship to Mandy was to tell him to shut up, just stop talking. Even when you tryna hype me up, telling me I’m the greatest thing since water, just shut up. In the writers room, we talked a lot about the pain body, sentient wounds, whatever you want to call them, egos. Once Mandy, for me, gets to the level of a whisper, I can really start to hear what the wisdom is there. You know what I mean? Like, why do you think I’m the greatest thing since sliced bread? Why do you feel the need to say that right now? Slowing the processes down so that the guidance of that sentient wound can be revealed is, I think, the way I’m starting to understand it. I’m not there yet.

KNOWLES: Okay, nice to meet you Mandy!

NANCE: No, I’m not Mandy!

KNOWLES: But he’s around?

NANCE: Yes, he’s around. Why the Pintos?

KNOWLES: I have no idea. It just came to me as a five-year-old girl.

NANCE: Did you like pinto beans?

KNOWLES: No. I think it’s a sonic thing. I just liked the way it sounds on the mouth.

NANCE: Okay, season three. We gotta do the Pintos.

KNOWLES: All right, there are a lot of initiations that take place in the show. I’m curious what initiations you might have been a part of in your lifetime, and any initiations that you might have rejected.

NANCE: So many. When I was a kid, I was in a program in my church called “Mandala,” which was led by the elders from our church, the men hat take us every Wednesday and basically initiate us into manhood slowly, because that’s the only way it could happen in the modern world. You know what I mean? I am who I am because of those men. They taught us how to articulate our bodies, taught us how to cook, taught us how to respect women, taught us how to be in conversation with each other, share our feelings, how to use our words in those ways. So it was a literal initiation.

KNOWLES: What a blessing.

NANCE: Shout out to Dwayne Johnson, shout out to Bill Crenshaw, shout out to Burt, just to name a few. And this is on top of what my father was doing and my uncle. It takes a village, period. So ultimately, I’m not the type of person that says no to any initiations, I guess. Any film I’ve attempted, or TV show, or even making an album, I’m sure. I’ve always had a moment where it was like, am I gonna do this? Especially if I know it’s going to test my spirit and my body and my capacity and bring me close to the edge? There’s always an opt out. And I’ve never opted out. Mostly because I’ve never felt like that’s an option.

KNOWLES: Scary Mary over here is jumping ship as soon as she hears the word initiation.

NANCE: Well, you got time.

KNOWLES: You’ve collaborated with some really brilliant directors. Frances Bodomo, but also so many other black women. How conscious and intentional are you about creating worlds where black women are in power?

NANCE: I’m very intentional in the sense that I make sure there’s a lot of Black women around the creative process. Conversely, it doesn’t require any intentionality. Those artists are my family. We move together. And I’m nothing without them. I don’t know a way of being without being in community and in relationship with black women, creatively, business-wise, you know what I mean?

KNOWLES: You often use portals in your work, be it through ancestral passages, mixed media or dark holes. You’ve shared with me your experience of many transportive moments of your own. What have you seen or experienced through these various portals?

NANCE: Man. a lot. I often see viscous black liquid. I see like, a being that’s made of that liquid, that kind of dances in a way that’s difficult to articulate in words. I see a lot of gold. And, I think, I hear things as well, different harmonics, different sounds that organize matter into different forms. In many portals, I understand the level of stakes at play with refining my own character, what to do and what not to do with my own spirit.

KNOWLES: You’re about to debut your first solo show, Swarm, at the ICA in Philadelphia and I’m hype for you. I’m really excited to see this new evolution of your practice. What are we about to experience?

NANCE: You gotta come see. Well, I think it’s just beautiful to have everything that I’ve done with all the people I’ve done it with—well not everything—but it’s a nice collection of things I’ve done over the years in one place to testify to the fact that we are here making this work to heal ourselves, heal the people. I’m just excited for you to come, and all the people that I happen to be in this lifetime with to bear witness to the moment with me. And then the music aspect of it; sound organizes everything in so many ways. So there’s an opportunity to listen to the album in a different way. And then I’m going to play some shows in Philly as well, with an orchestra and like, really express the album in a way that’s new.

KNOWLES: I’m excited to pull up then. It’s ’bout to be a vulnerable time for you. I’m about to have my first performance in four years.

NANCE: Wow, it’s been four years? Wow. I guess it makes sense. We lost two or three of them.

KNOWLES: I’m overjoyed about this revolution of young black artists creating their own hubs and institutions and homes for their own and their tribe’s work. Nothing brings me more joy. Can you tell me about the film studio you’re creating, and what the ethos of the studio will be?

NANCE: So we’re creating films to be in Baltimore. It’s called Lalibela, and the intention is to make sure that there is a well-equipped, sacred space to express cinema and all the other things we’re doing. It comes from observation that often we’re making places work to do that. We’re kind of like, “that place will work,” and we figure it out, then we leave that place, and it has some residue of the energy we brought to it but it doesn’t accumulate. And Lalibela will be an accumulation of our intentions to make cinema that heals, make sound that heals, make movement that heals. And it’s not metaphorical. That’s what we’re doing. People don’t realize that they get through hard moments—they get through divorces and breakups, they get through baby showers and big celebrations with a song—because somebody put that intention in that song. This is some surgery going on, you know what I mean? And the space has got to be well-equipped for that type of work. I’m excited to be in that space-making project with the city of Baltimore, with the people I’m doing it with who are all bringing that intention in different disciplines, different ways, different modalities, different disciplines. It may not happen tomorrow but we talking shit until it’s there. Because you know, that’s how things happen.

KNOWLES: I can’t wait. I’m gonna end this with Texas trivia. Big Moe’s “Barre Baby” or Big Hawk’s “Chillin Wit My Broad”?

NANCE: I’ve only heard the first one. What’s that?

KNOWLES: I’m chilling with my broad, and you already know / And if you wanna reach me, hit me on the down low / If I don’t call back, don’t put on a show / When I pass by your house and blow, instead of knocking on your door.

NANCE: That’s amazing that you remember the exact name of that song. I’m gonna embarrass myself and go with I don’t know, number two. But I like that better the way you just did it.

KNOWLES: Damn. You were already probably at NYU or some shit by that time.

NANCE: I definitely wasn’t because I’ve heard that song. I just didn’t know the artist or name at all.

KNOWLES: Okay, well, you gotta bump tonight. That concludes my questions.

NANCE: Thank you so much.

KNOWLES: You’re welcome so much.

NANCE: I’m so appreciative of you.

KNOWLES: Thank you. I’m so appreciative of you, too.