IN CONVERSATION

Sedrick Chisom Shows Kara Walker His Apocalyptic Vision

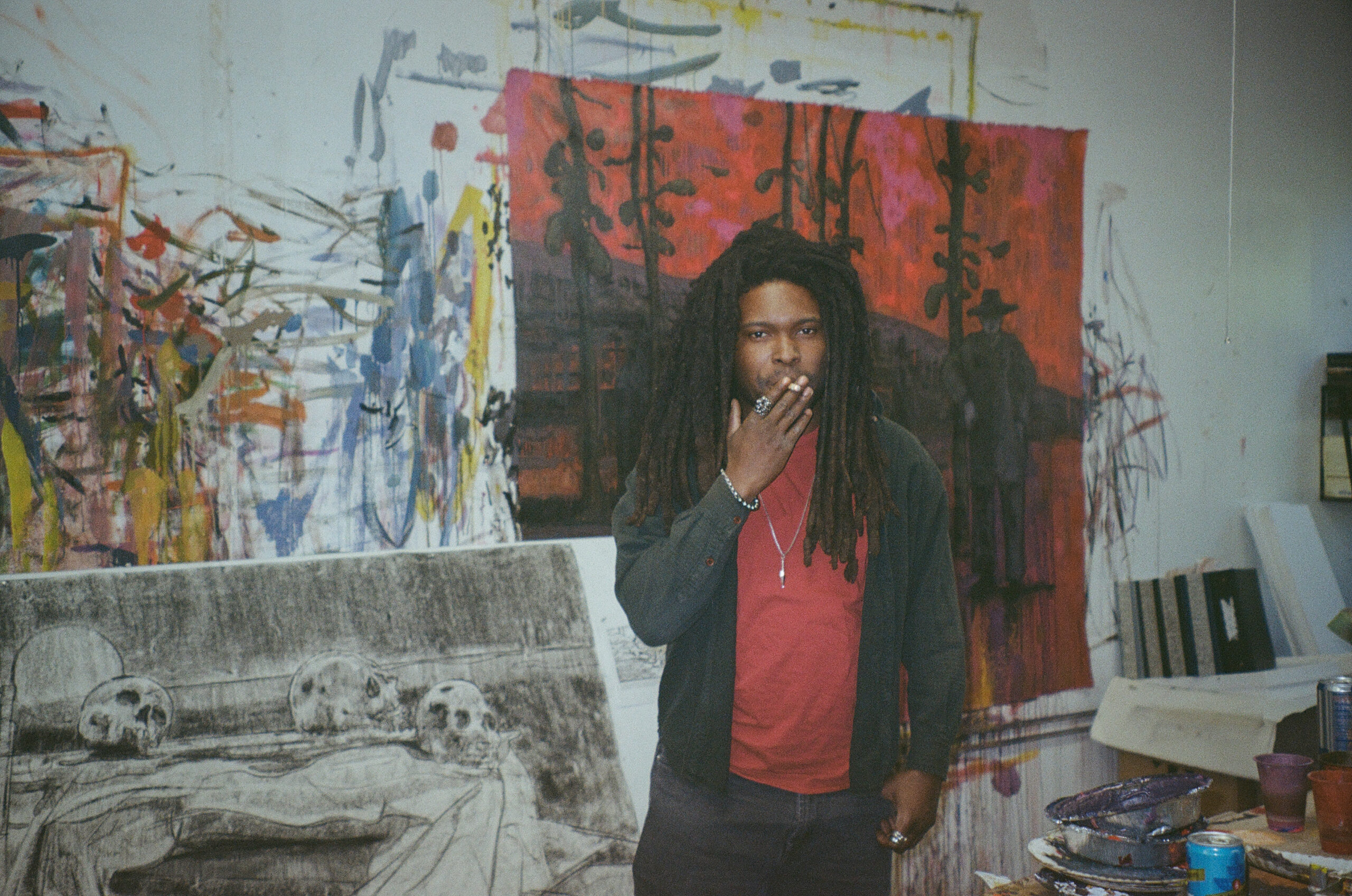

Sedrick Chisom, photographed by Nancy Kote. Courtesy of C L E A R I N G New York / Los Angeles.

Sedrick Chisom’s paintings have often supplied us with accounts of a fictional war taking place in a nation that lives under white supremacy, featuring scenes of isolated characters traversing a desolate land. The paintings included in his new solo show, The 108 Prayers of Evil, continue in the tradition of such fantasies, but provide a new string of narratives that depics both unrest and an attempt at unification. “The basis of their unification is negativity, in order to banish this outside figure that invades their thoughts,” says the artist on a call with friend, painter, and MacArthur fellowship recipient Kara Walker. “This is in the background, and the foreground is citizens of this fictitious white supremacist country murdering each other, burying bodies, and skeletons in rivers.” Opening today at C L E A R I N G, the show title gets its name from the prayers sung by the Buddhist savior in order to rid the world of its vices. On the day of the solar eclipse, the two artist’s talked about everything from dystopia to utopia, Lacan to Freud, and Chisom’s love of anime.

———

KARA WALKER: It’s been forever since I’ve seen you. We ran into each other—

SEDRICK CHISOM: —on the steps.

WALKER: —at PS1. I did not prepare questions for you.

CHISOM: That’s okay. Here are a ton of questions for you.

WALKER: I’ll bet. Well, this is a one-way street. You are the featured focus of our interview. When is your show coming up?

CHISOM: My first solo show in New York is May 1st. The shipping’s actually in a week-and-a-half.

WALKER: Oh, wow.

CHISOM: I’m really in the trenches on this one where I was like, “Screw an eclipse.”

WALKER: So that work is almost ready?

CHISOM: Yeah. I just have to make a few drawings. The paintings are done to the extent of how neurotic I get the longer I look at them.

WALKER: The question I wrote is, “What are you working on?” But really, what are the themes? Where have you gone since I last saw you?

The Citizens of The Capitol Citadel Disregarded its’ Volcanic Tremors Which Could Be Sighted from Several Nautical Miles Away, 2024. Acrylic on canvas. 60 x 74 inches.

CHISOM: Well, in the past few years, there were identifiables in terms of the Confederacy, the Wild West, and particular sci-fi tropes. I keep pushing myself forward in this imaginative narrative. The further into the world I get, it resembles our own world less and less, and goes more into fantasy elements. In this body of work, there’s a sparseness to the spaces that are populated. The figures seemed lonely in the past, but now they’re even more desolate.

WALKER: To clarify, the fantasy element was the fantasy that white supremacy has of itself, particularly in America. So the Confederacy, the Civil War and Wild West iconographies materialize figures enacting?

CHISOM: Yeah. I’d say the figures were typically undermined in their position, so they’d be reaching altitudes that they couldn’t climb down from, or they’d be falling into ice floes and drowning, or they would be completely lost in the wilderness. They were not the master of their circumstances at all. So at this point in the narrative, they’ve achieved their dream. They’ve conquered their imaginative and literal territory, but there’s an internal disharmony, they’re not happy with themselves.

WALKER: Of course.

CHISOM: They start fighting each other, there’s massacres.

WALKER: The logical outcome of this fantasy eradication. Did you read The Turner Diaries?

CHISOM: Yes.

WALKER: It’s hard to read.

CHISOM: It’s really hard to read because it’s not well written. That’s the insulting part of it. Do you know the French book, The Camp of the Saints?

WALKER: No, I don’t.

CHISOM: It’s the equivalent of The Turner Diaries. It’s about immigration and refugees going to Europe. But it’s actually well written. In a weird way, I started feeling bad because I’m like, this is the worst moral principle of our American literature, but it’s also aesthetically bad. But when the literature is good, even though it’s morally bad–

WALKER: That’s complicated. It seems fitting with America’s version of racism. Because it proves the point that it shouldn’t really work here. If we were to stand behind the principles of the American foundation, all the genocides that have happened, it seems like it could have gone another way.

CHISOM: I’ve been reading a lot of texts on dialectics, and there’s principle contradictions and societies at a given moment, and then there’s a principle contradiction at the instantiation of a nation. Ours is literally a nation created under an idea of freedom, but that required mass unfreedom at the same time. The spirit of this country is this collective lie that we buy into that contradicts the reality of how the country even came into being. That’s the foundation, but it’s not sturdy, intellectually, if we break it down.

WALKER: Yeah. And it doesn’t serve anybody to do so, because it’s so destabilizing to recognize that this is not working. Like Cowboy and Indians movies, those tropes normalize shaky ground. I remember when I popped onto the art scene without any vetting from anybody, there was a thing where there was only room enough for one Black woman at a time.

CHISOM: Was there beef?

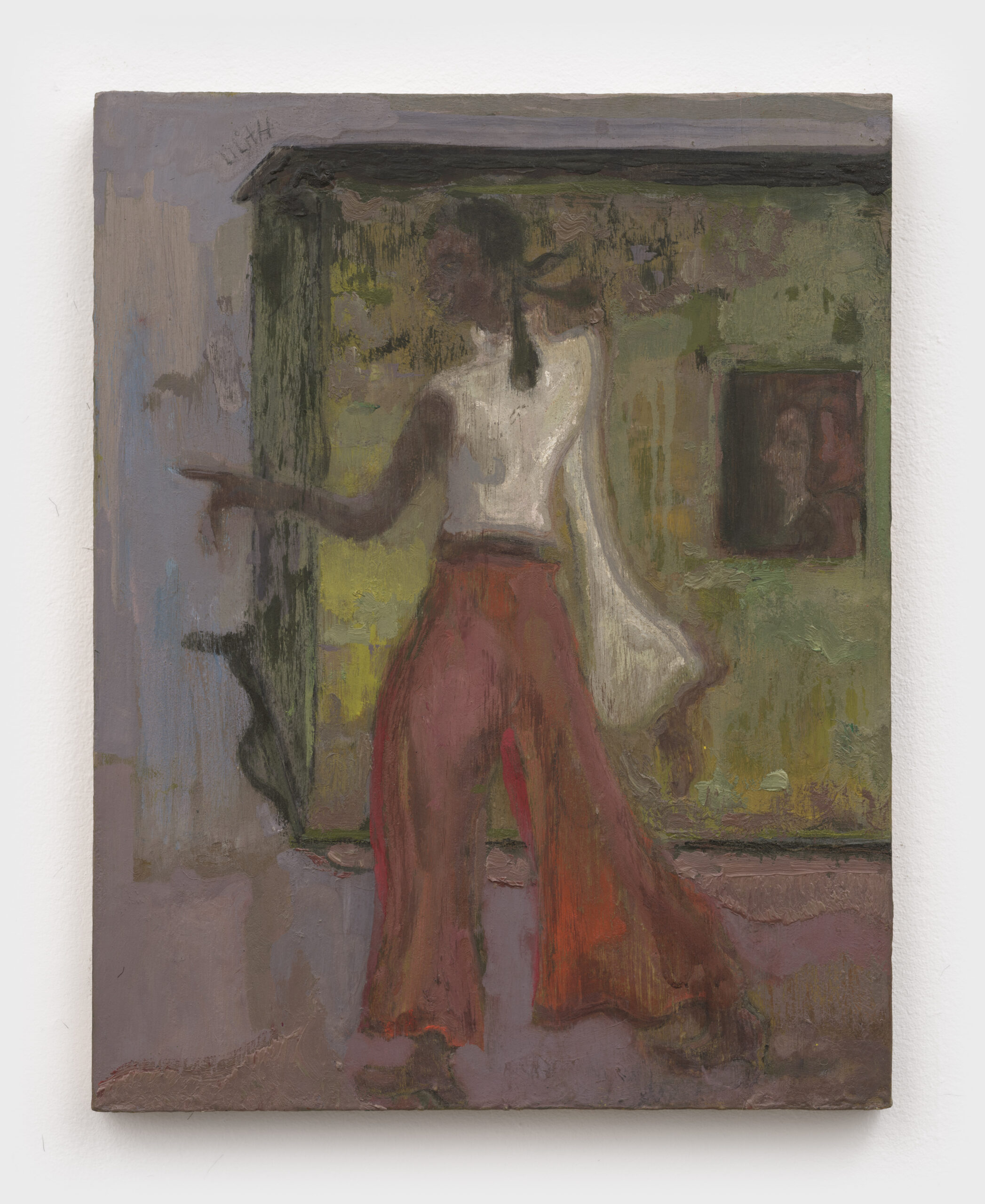

Untitled, 2024. Oil on paper. 11 x 14 inches.

WALKER: I didn’t have any beef with anybody.

CHISOM: Yeah. But that’s the thing, the sense of competition is internal in the sense that it’s not. You are pitted against someone who has an identity like yours, because the condition that you’re in is a white supremacist class society.

WALKER: It’s the battle royale from an invisible man. Your work now, you said you’re moving the narrative into a terrain that’s more about right now?

CHISOM: It was the opposite. The show for C L E A R I N G is titled The 108 Prayers of Evil. It’s an inversion of the 108 prayers that the Buddhist savior figure sings to rid the world of vices. The basis of their unification is negativity, in order to ritualistically banish this outside figure that invades their thoughts and to distract themselves from their internal unrest. This is in the background, and the foreground is citizens of this fictitious white supremacist country murdering each other, burying bodies, skeletons in rivers, and implications of violence that didn’t erupt from the external source.

WALKER: Right. Does it ever feel debilitating to a sense of Black self, to have these rampaging white supremacist-like fear fantasies? Because, their fantasy ideal is to eradicate all difference, right?

CHISOM: Exactly.

WALKER: So at what point do they achieve uniformity? Where have all the other people gone and what has happened with the coloreds?

CHISOM: Well, the logic of fascism is the eradication of contradiction of difference, of multiple narratives and multiple cultures. I was listening to a podcast on the superego, which is the Freudian concept of internalization of morality and law. They were saying that to cede to the superego means you’re constantly giving to this purification ritual that can actually be achieved. To rid the world of this contradiction, you’d have to kill every single person on the planet because differences would become more and more-

WALKER: Right. It would keep multiplying.

CHISOM: Yeah. It’s an endless task.

WALKER: This is a pivot, but I was wondering about the way that you paint and if there’s something in the way you use materials that correlates or contradicts this world of pureness? Or if your painting is speaking a separate language?

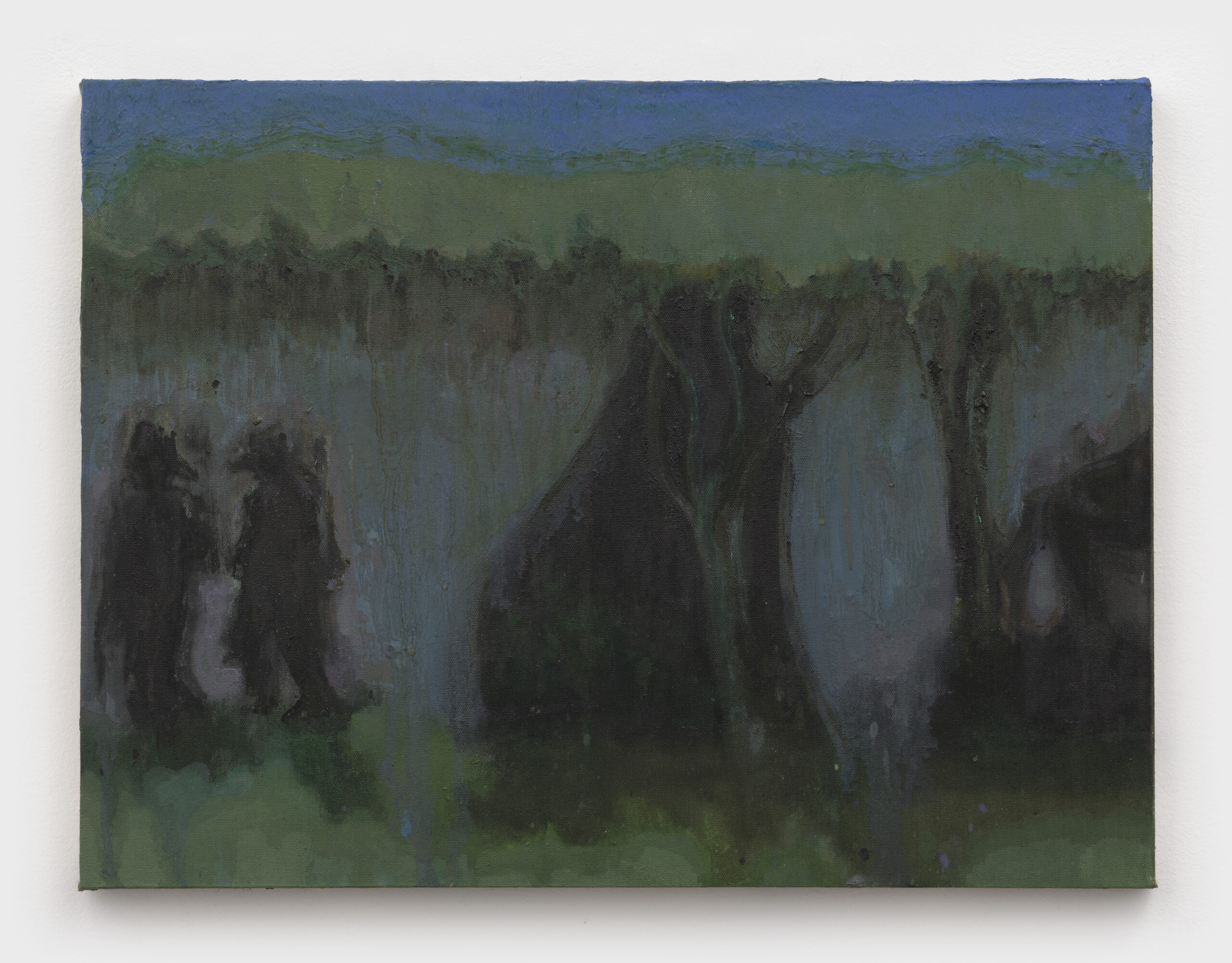

A Soldier of the Southern Cross and His Dog Travelled a Hundred Nautical Miles From a Place They Didn’t Belong to Murder the Bog Troll in a Place He Didn’t Belong, 2024. Oil on linen. 54 x 73 1/2 inches.

CHISOM: The painting is about contamination. Using really muddy paint, using really clear paint, layering it in a particular way that the surfaces become distressed, layering it and scrubbingit and spraying. I try to approach the paintings with a sensitivity. There’s a sensitivity to the color and light and edges and modifying these things. But on the other end of it, I’m just trying to subtly modulate the edge of a severed head. So there’s a kind of presentness and a sweetness, but on a level of material and color, there’s a violence in the image. The image seems like it’s like a fugitive, like it’s about to run off the surface. Because of the verticality of the drips, the figures seem like they’re under a sense of pressure or weight. The sense of ground isn’t clear. They’re these miasmas that sometimes materialize into identifiable forms. There’s this area that becomes a house, and then it’s like an abstracted color field moment thereafter. The worlds are really unstable, and this is how I see it. Something that’s abstract.

WALKER: Abstract, ethereal, transparent even a little bit sometimes?

CHISOM: Yes, moments that are transparent, moments that are really opaque, but then there would be an opaque layer that’s sanded down, or I literally mess up the process and it lifts the whole thing off.

WALKER: Skinned.

CHISOM: Yeah, skin the paint. Quite literally.

WALKER: To your point about fantasy of a pure space, I was thinking about Timothy McVeigh and the nineties terrorists who really wanted to instigate the race riot. I was thinking, who’s going to clean up this mess when they’re finished eradicating us? You’re going to have to keep some colored people around to clean up all the bodies, because it seems like the fantasy is not well thought through.

CHISOM: Do you know [Slavoj] Žižek? He’s a Lacanian psychologist that brings up how a revolution is traumatic. You actually can’t go to that space in a cinematic vision of what would be the day after tomorrow, to see what the consequences would be. And then I was listening to a podcast about the Capitol riot, and they were saying they actually got into the Senate chambers pretty easily, and as soon as they got in, all they started doing was taking selfies.

WALKER: They didn’t have a plan.

CHISOM: They ran out of things to do. A centralized government this big will be hard.

WALKER: I know, right? There’s a lot of chairs.

CHISOM: Yeah. I was reading on the Haitian Revolution, where some of the central figures start switching sides between the French and the Haitians, and the conditions become unbearable either way, because a liberated Haiti would’ve been equivalent to slavery in order to modernize to begin, and then saddled with debt.

WALKER: Constantly exploding. You do wonder if the big fantasy around America is money. We’re often teetering on the brink of collapse, and we keep reinstating the initial desire for economic and religious freedom. It’s almost like the patriotism that somebody has who’s become a lifelong New Yorker, where you know that the city is constantly teetering on the brink of its own physical and psychological collapse.

CHISOM: It’s so impressive.

WALKER: Every day that works is a miracle.

CHISOM: Yeah. Like in Times Square, nobody gets hit by cars. The people dressed like Spider-Man, Superman and SpongeBob aren’t killing each other.

WALKER: Yeah. It’s not safe, but there’s not a full-on catastrophe at present. When there is a catastrophe, there’s this concerted effort to change our minds about it because the trauma of collapse is too great. Too big to fail.

CHISOM: Yeah. We’ve had these economic downturns and shorter and shorter cycles. It’s the government bailing it out every time. Low-key, we don’t want absolute freedom. Everything would fall apart and people would lose their livelihoods and starve. But there’s no acknowledgement that big government is actually keeping this engine going.

WALKER: Parts of it, anyway. It’s true.

CHISOM: It’s like animating a corpse by electrocuting it a few times to get some juice. I keep thinking of these fantasies as escapism, because people feel that their life has a limit that they can’t overcome, and they have a fantasy of a victory over the immediate reality they’re facing, which secures them and offers them mental security. But the thing that’s not addressed in these fantasies, is that you would still have to work. There would be no external guarantee of your sense of meaning in the world.

WALKER: You watch a lot of sci-fi and anime?

CHISOM: Yeah. Keep that under wraps.

WALKER: No, I want to know.

CHISOM: What of it?

WALKER: I was wondering about ways that it’s fueled your imagination or the ways you think about moving between paintings.

CHISOM: In the anime I watch, they always have celestial events happen, like the sky cracks open, a thunderbolt comes out the ground, an earthquake, or the ground is rising up. I’m really drawn to anime with apocalyptic tones. I grew up watching Dragon Ball Z, and the first arc in the whole series is the main character on an alien planet. The planet’s going to erupt in three minutes, but it’s 80 episodes long.

WALKER: Oh, wow.

CHISOM: Yeah. He’s fighting an alien racist tyrant who’s killed all of his race. He’s come back for revenge, he’s trying to wipe out this other planet.

Untitled, 2024. Oil on canvas over panel. 18 1/8 x 24 inches.

WALKER: That’s so cool. How old were you when you started watching this?

CHISOM: I was in daycare.

WALKER: Okay, so it’s deep. It’s in there all the way.

CHISOM: It was a deep cut. There’s a James Baldwin documentary, I Am Not Your Negro, and he talks about the Cowboys and Indians, and when he watches the cinema, he identifies with Native Americans. Then when I saw Dragon Ball, even though it’s Eastern Asian/Japanese culture, there’s a fictitious alien race called Saiyans, and then there’s humans who seem more westernized American, and then there’s these aliens. I identify with the Saiyans. I was like, oh, you got to get your revenge.

WALKER: Yeah, of course. And sometimes you just see it when you just look at them and you’re like, “Oh, yeah, that’s me.”

CHISOM: Yeah. They don’t necessarily represent you, but they reflect you in a certain way. I keep thinking that there’s still this desire to get to a beyond of some kind, either in cyberspace, AI and virtual reality, or you hear every day that Elon Musk is aiming a rocket at Mars or something.

WALKER: I know. Like, what are they going to do there?

CHISOM: Nothing here is enough. There’s this impulse to have access to an elsewhere. And it’s not as though it will alleviate whatever conditions you have currently.

WALKER: Right

CHISOM: It’s a perpetual thing. I can’t imagine a frontier beyond outer space or cyberspace, but I do have to say when ChatGPT came about, I was like, artists are going to try to use this and innovate and have other modes of making. And I started using it and I was so disappointed.

WALKER: It’s really dumb.

CHISOM: I realized the model for AI is fraught, because AI basically parrots human behavior.

WALKER: Well, that’s everybody’s fear. Because they only have this to go on, and it hasn’t done very well historically.

CHISOM: I remember early AI, where you would make an image of a cat, and it would have 40 eyes and two heads. I was like, whatever machine intelligence this is, it’s not remotely close to a human.

WALKER: Yeah. It’s very good at doing the uncanny, but it’s not what we hoped for.

CHISOM: I wanted it to imagine something I couldn’t.

WALKER: Yeah, and it can’t because it doesn’t have a history or a body or a set of experiences, it just has information. It doesn’t have pain or feelings. All of our senses of selves and of history and how we project into the future and how we imagine the past is all based on having burned your hand or been ostracized.

CHISOM: Absolutely. One of the first things you notice about an image made by AI is it doesn’t understand tension. It doesn’t understand how close people are in a space, it doesn’t think about what eye contact means.

WALKER: This is a spit-balling question: Who are the painters you want to paint better than?

CHISOM: That’s a good question. I guess Titian, [Arshile] Gorky, Balthus. I have a lot of problems with dead people.

WALKER: I hope they don’t have a problem with you, man.

CHISOM: Oh, I’ve read their biographies. They typically did. I went to this Munch exhibition and something that was really wild to me was, if I have kids, one of these paintings in an exhibition will be seen by them and then probably by their kids if the world lasts that long. It’s like a trace of evidence of a dead person who’s dust at this point, flexing on you from beyond the grave. I was looking at it and I was like, shit, that guy could paint.

WALKER: Yeah. We should go. I have my eclipse. Good luck with everything. Send me an invite.

CHISOM: Absolutely.

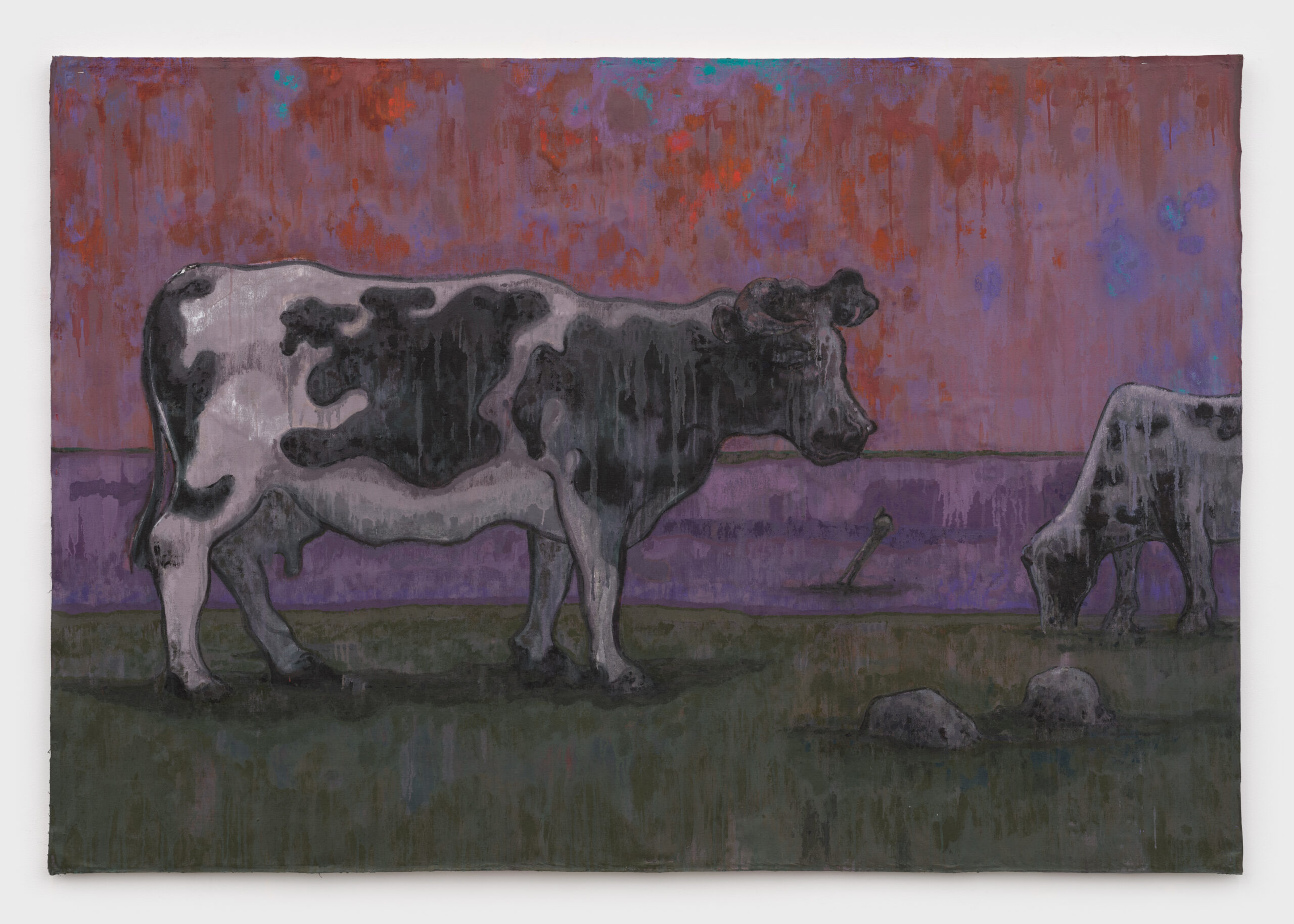

A Gift of Cows was Offered in Place of the Circassian Beauties that Were Promised to the Sons of the Southern Cross During Its Year of Acorns, 2024. Acrylic and spray paint on linen. 52 x 75 3/4 inches.