The Recurring Sara Cwynar

Sara Cwynar is a multi-disciplinary photographer who grapples with the photograph: in terms of its history and its role in building a shared worldview. Among the unending swell of visuals that we confront in our daily lives, her sculptural and manipulated photographs break down the smooth edifice of the commercial image, and force us to look again. While most photographs we see are re-touched and falsified in their presentation, her work deliberately bears an index to reality on its surface, and feels nostalgic for analog means.

With an upcoming solo exhibition at Foxy Production, “Flat Death” seeks to provoke our conceptions surrounding kitsch and images, in both cultural value and consumption, and how time can act as an equalizing force, often converging these notions together. We sat down to talk more about her ideas behind the show.

JACKIE LINTON: You were recently inspired by the book “Roman Letters” by Evan Calder Williams, and I notice that Roman columns are a visual metaphor that appear both in his book, and in your work. What attracts you to the idea of these columns?

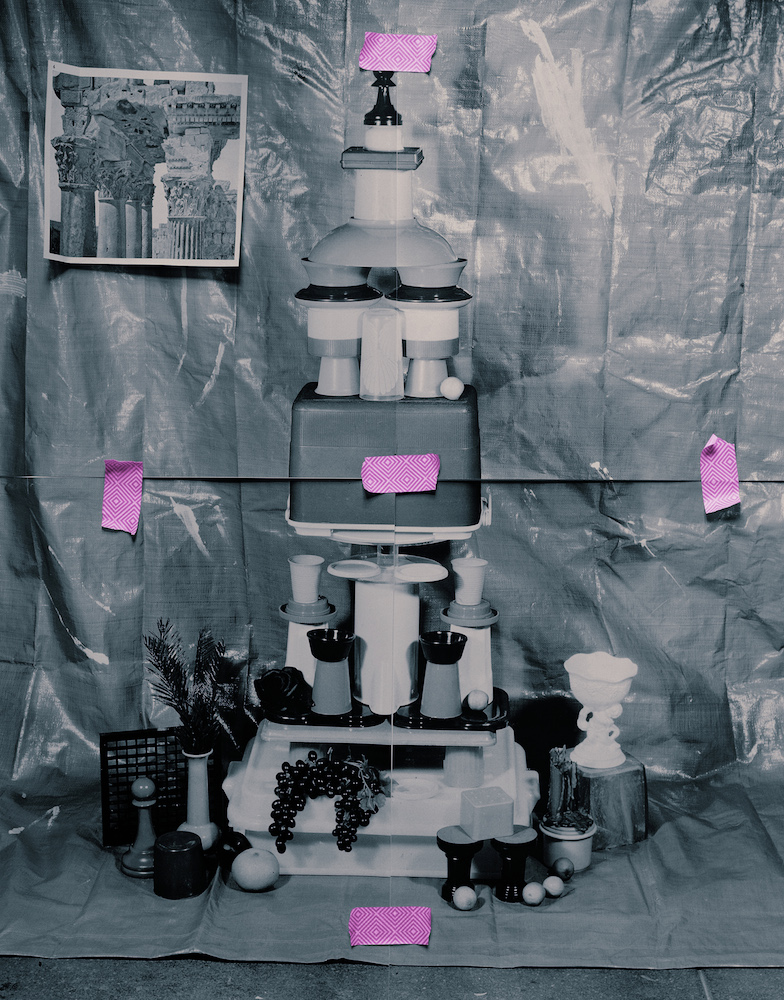

SARA CWYNAR: I love that book so much, but I didn’t read it until I had already made the work—and I just wanted to high-five him when I came across it. One thing I’m drawn to that he talks about is the commodification of these tourist sites, and how a drink, or a hot dog, costs more if it’s in the shadow of the monument, than if it’s bought around the corner. I really like the idea that these types of relics are supposed to hold history and meaning, but that they’ve been emptied of it, and turned into a commodity. It becomes a thing that just people take pictures of, that resurfaces in vacation snapshots, tourist guides, and encyclopedias—and how far these images have come from their original meaning or the historical context they once had. In the column pieces, I am collecting examples of where these architectural qualities have manifested themselves through party cups, and in these cheap objects that everyone has in their house, things that I find in Goodwill, or junk stores, or places where they’ve been intentionally discarded.

LINTON: The Roman dynasty was so far back that we don’t recall that much about it, no negative subtext of wars, travesty or bloodshed.

CWYNAR: Yeah, it speaks to an idea that Nietzsche had of “eternal recurrence,” because this history can’t come back, and whatever happened in Rome will never return, so we’ll just turn it into however we want to remember it, including these pillars of civilization, literally, becoming plastic party cups or junk objects—that’s the aspect of kitsch that I’m interested in. People will often look at the floral still lifes I make and say, “Yeah, this is kitsch, so what’s the point?” But the more meaningful version of kitsch is that even the darkest moments in our history can become however we want to remember them. Images play a large contribution to how that happens, creating a specific history that everyone knows and remembers, and erases what happened before.

LINTON: The flower arrangement still lifes are sculptures that are building on what was previously there—the arrangements of objects you’ve collected are built on top of an archival image of flowers. It’s almost how culture tends to build on itself, flattening the past, so it can be built upon further.

CWYNAR: Well, yes. Remaking the floral arrangements, resurrecting the image with these discarded, junk objects—it’s this idea how we are constantly adding more materials to our lives, flattening and emptying the past, and it cycles over and over. A lot of the objects that remake the floral still lifes are intentionally these synthetic faded plastics that make these weird colors. They are supposed to mimic the way the original photograph has sort of faded and warped over time.

LINTON: Do you collect objects or images from a particular era?

CWYNAR: I collect images from the ’60s and ’70s, mostly. It was sort of the end of this idealism in printed matter. National Geographic presented this sort of naive modernist ideal, an idea that they could bring the whole world to the viewer through their images. Now, we look back, and these photographs seem like such contained objects in their presentation, pre-Internet, and you can really see them as an encapsulated units of knowledge. An encyclopedia, for instance, claiming to contain all knowledge from A to Z. Bringing the world to you through this one 150-page magazine. Now, this idea is impossible.

LINTON: There are a lot of reversals at play in your work—what’s beautiful is made of junk, what is flat is really sculptural. And while you’re trained as a skilled graphic designer, formerly at The New York Times Magazine, you incorporate an excruciating obsessiveness in crafting these analog images. I’m sure it would be much easier to make these works on your computer.

CWYNAR: Oh yeah, totally. There’s definitely that compulsiveness or the need to “work”—I am really reluctant to use the word “Marxist,” but my work contains some of these politics. It’s something I’ve come about through my own obsession through collecting, buying, and consuming, and being in this industry where you don’t even think about it, working as a graphic designer and making commercial images. I don’t think I’m above it, but I think that’s what plagues me, and why I want to make art in an analog work practice.

LINTON: You feel the need to put yourself to the test of actually making things.

CWYNAR: Yeah, these images have to exist as real things. I can’t just create something that looks like the image I have in my mind. The idea is also rooted in this obsession to make an external version myself through objects. Christian Boltantski says this really well, that by making this other version for myself, “I may finally rest.” He can go on existing through this archive and constructed version of the self.

LINTON: You’ve also mentioned that you’re going against the grain of Internet consumption—attempting to slow down the smooth process for people to consume your images, by incorporating these production dualities, creating trompe-l’œil effects.

CWYNAR: As nostalgic and analog as my work is, it’s often responding to the Internet—I’m not just fetishizing these images, but responding to the way we experience images now. You look at my photographs, and you read it in an instant as you do with everything, and then hopefully you realize, “Oh, wait, it’s not quite that”—maybe you could think about everything you’re looking at a little bit more, maybe you notice some of the objects as things you own or relate to, or you could have the process thrown into question.

LINTON: Much unlike a computer desktop, your studio has heaps of archival images everywhere, sorted by vague, often poorly identifying categories: “outdoors,” for instance, or the color blue. In the same way that your work disrupts the idea of smoothness, your practice of producing these images seems to be trying to break down a smooth process. The production looks crazy—and the photographs often take more than a week to make.

CWYNAR: [laughs] Well, one thing is that I collect at a faster rate than I can organize. And I have an ever-expanding non-hierarchical archive in my mind. For instance, I know I have this amazing image of a tambourine somewhere in my collection, but I just have to find it. And then I’ll find 10 other things in that process of finding it, so it’s generative. If I could, I would probably try to organize it more… [pauses] There is an organizing principle! But it’s just not very articulate, nor very good.

SARA CWYNAR’S “FLAT DEATH” IS ON VIEW AT FOXY PRODUCTION GALLERY IN CHELSEA STARTING TODAY, APRIL 4.