Inside the Sammlung Boros

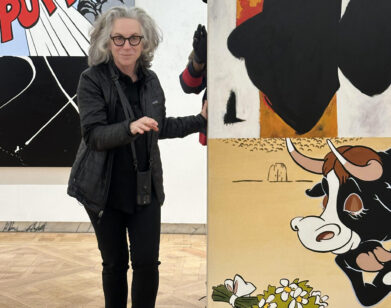

Art aficionados Karen and Christian Boros’ collection is comprised of more than 700 art works from every genre and recent movement, beginning in the early 1990s. The husband and wife store a portion of their vast collection near the heart of Berlin in a former bomb shelter—built in 1943, designed by Albert Speer, and known as the Bunker—which, by appointment, visitors to the city can view. The Boros held their first by-appointment exhibition at the Bunker in 2008, and although it formerly housed everything from tropical fruit to sadomasochism parties and prisoners of war, the looming space now displays the second showcase of pieces from the Sammulung Boros.

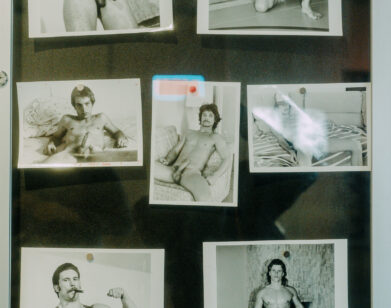

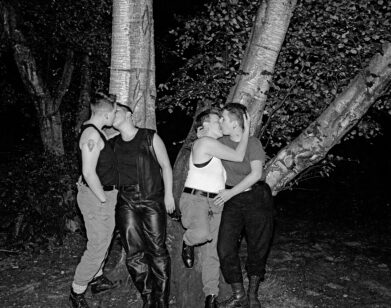

Upon entering the building, the sticky smell of popcorn drifts from some unknown upper level, the result of an installation by Michael Sailstorfer of an unsupervised popcorn maker, which for the past two years has contentedly churned out kernels, nearly filling a room with undulating movie snacks. Moving further into the space reveals works by the likes of Thomas Ruff, Danh Vo, and Thoms Zipp, amongst several stark photographs by Wolfgang Tillmans, a grim room for teenagers designed by Klara Lidén, and a two-story tree made by Ai Wei Wei, which required the removal of a floor to install.

Earlier this month, I met Christian and Karen during Berlin Gallery Weekend. We sat in the glass-enclosed apartment they added atop the building, surrounded by books and more of their art, with the lingering buzz of a just-completed party for friends and distinguished guests. We spoke about the collection, their own history, and what’s next.

ZACK NEWICK: How did you two meet? Were you brought together by your interest in art?

CHRISTIAN BOROS: Yes. I met Karen at the Art Basel fair. She worked for a gallery representing Ed Ruscha. I collect contemporary stuff—not Ed Ruscha—but to impress her, and to be in contact with her, I bought an Ed Ruscha. Now we are married. That Ed Ruscha is in our bedroom.

NEWICK: Growing up, which artists were most important to you?

CHRISTIAN BOROS: For me, it’s Joseph Beuys and Carl Andre—my heroes. They’re completely different, of course, [but] for me, Carl Andre is the best minimalist, much better than Donald Judd. Judd is a decorator; Carl Andre is really a radical. And Joseph Beuys is the godfather of German art. I met him [when] I was 16, and I met Martin Kippenberger when I was 17, and they changed my life. And for you?

KAREN BOROS: Duchamp. I never met him, but you know Duchamp is still a fascinating figure. His work is not finished.

CHRISTIAN BOROS: You are much more intellectual. [laughs]

NEWICK: How many years were you collecting for yourselves before you said, “Maybe we have something worth sharing here?” Was it a hard decision to open it to the public?

CHRISTIAN BOROS: About 20 years. It’s stupid to buy art and put it in storage. Sharing art, that’s the best thing. Look, it’s Gallery Weekend. A lot of people are here from Sao Paulo, New York, London. For us, one thing is absolutely clear: we love people more than art. People are much more important than art. To share art with people, to meet new people, to discuss art, that’s the reason why art is made.

NEWICK: When I arrived here, you described this space as a kind of hell. Do you really feel like you’re putting people through something arduous when they visit the Bunker?

CHRISTIAN BOROS: It’s typical Berlin. Berlin has a hard, strong history and we want to show art in this context, in this Berlin context. It was hard to think about buying the Bunker, but we asked artists, “Is it okay?” And they said it is much more than okay; it’s necessary to put art in a bunker, because art is a form of freedom—freedom of thinking, freedom of opinion. All the dictators are afraid of art.

NEWICK: And so have you changed what this place is for? Or will that history always be a part of what this space is about?

KAREN BOROS: For us it’s always still related to the history. We tried very much to change it and open up the space to be able to install artworks inside, but in a lot of situations you can still feel the claustrophobic situation, the threatening situation of what it was originally built for. That was very important to us. We could have painted all the walls white and it would have had a different feel to it, but it still has this roughness.

NEWICK: Has the kind of work you choose to collect changed at all because of owning the Bunker?

CHRISTIAN BOROS: No. We collect important pieces of art, not pieces that fit in the building. We bought last time a piece that never fits in the Bunker because the doors are so small. Our aim is not to decorate the Bunker with art. If an artwork is important for us we will buy it. If it fits, always we ask the artist, “Could you install it in this difficult surrounding?” Because it’s not made for showing art. It was a perfect bunker, but not for art. I like when it’s not perfect.

KAREN BOROS: We have a lot of visitors who also come to experience the Bunker as what it was built for. And I like it because they have to come and see it and also look at contemporary art, which they may never go see in a gallery. And that’s how they are kind of, not forced, but they see these works and hear something about it, and may get a good introduction, may go on and even like a few.

NEWICK: Do you think of this as a gallery? Something between a museum and gallery?

CHRISTIAN BOROS: It’s not a museum. It’s a very special, private collection, because we are special. You cannot compare us—we are not curators, we are not gallerists. Gallerists want to sell art; I buy art.

NEWICK: How has the Berlin art scene developed in the years since the first show in 2008?

CHRISTIAN BOROS: More and more private collections come to Berlin, not only from Germany. We spoke to a couple from Argentina planning to show a collection in Berlin. Berlin will not only be a city for artists and for producing art, but a city to share art because you can find very easy, interesting spaces. It’s not very expensive. You can’t show your collection so easily in New York.

NEWICK: Is the vibrancy of the Berlin art scene driven by the fact that artists can afford to live here?

CHRISTIAN BOROS: Of course. That’s very important, but not only cheap space is important. Cheap space you have everywhere in Germany, but cheap space and people coming from the whole world—to be a hub, to be a spot where the discussion about art is important, that’s in Berlin. We are not talking a lot about money. I just came from London, [where] I visited with a friend who said, “Here people are only talking about the money part of the art”—in New York maybe too. Here we are talking about the content, because here we don’t have money. [laughs]

NEWICK: Downstairs, everyone is asking about when the next show will happen.

CHRISTIAN BOROS: The next show will be very young. Here you see some old possessions from our collection, like the Thomas Ruff photographs from the ’90s. You see some new acquisitions like Klara Lidén and Sailstorfer as well, but I think the next show will be very contemporary.

KAREN BOROS: Usually we like to show some of the new acquisitions, but we also haven’t seen artists’ works like Michel Majerus or Franz Ackermann [for a while]. We’d like to have a dialogue between these artists based more in the ’90s and then 20 years later. It will be both [and open] next year.

THE SAMMLUNG BOROS IS LOCATED IN BERLIN. YOU CAN SCHEDULE AN APPOINTMENT TO VISIT VIA THE WEBSITE.