Love You, Mean It

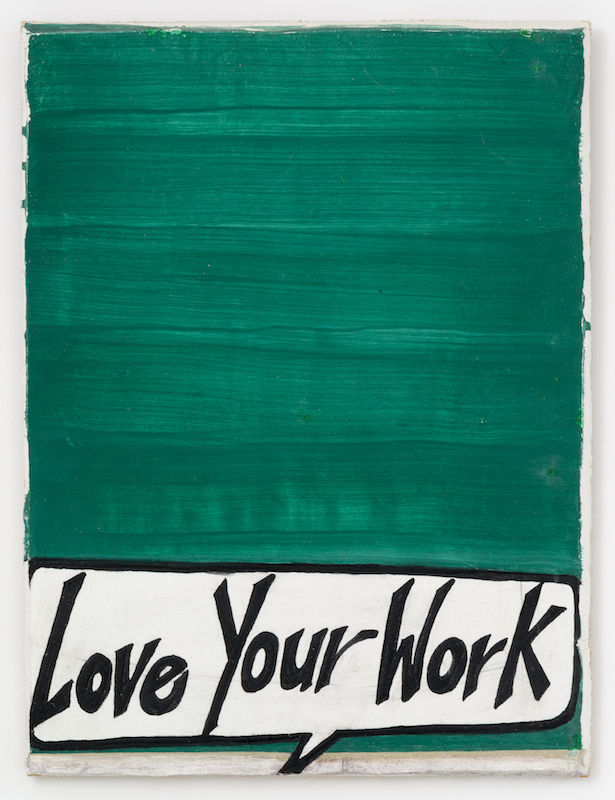

ABOVE: ROCHELLE FEINSTEIN, LOVE YOUR WORK. PHOTO COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND ON STELLAR RAYS

Rochelle Feinstein is skeptical of your flattery—especially one particular phrase.

“It’s one of what I call ‘Life’s Three Great Lies,'” says the abstract painter, pointedly. “Things you can’t really trust that people say quite often. One is, ‘The check is in the mail,’ another ‘I won’t come in your mouth, I promise.’ And the third one, for the art world, is ‘Love your work.'”

Feinstein, also Director of Graduate Studies in painting and printmaking at Yale, has long been interested in exploring such perplexing social codes in language. Through her signature marriage of abstract forms and text, her work calls attention to frequently used idioms and platitudes that impersonate opinions and beliefs, conveying no real meaning or insight. Together, they comprise a kind of “filler speech” that serves only to provide the speaker with a sense of validation.

At On Stellar Rays gallery this Thursday, April 10, Feinstein will be unveiling “Love Vibe,” a singular painting installation comprised of six large-scale canvases that include variations on the “Love your work” phrase, prompting viewers to think about their response to the work before they even begin to consider it. Feinstein hopes this experience will inspire a greater sense of accountability within them, reminding them to choose their words carefully. “Each of the paintings is done through a kind of meandering perspective, which challenges you to think about where you’re looking and what exactly it is that you’re referring to when you’re responding to it,” she says, explaining the set-up of the installation. “Can you point to the thing that you say you love? Are you sure?”

NOOR BRARA: What’s the story behind Love Vibe?

ROCHELLE FEINSTEIN: It came out of language—I’m interested in mnemonic speech. The basics we understand, and how we use them and what we think they mean, which is something I’ve been exploring for the last few years and is a thread throughout my work. This piece sort of came about after I got a particularly brutal review. I’ve always been interested in the ideas of perception and cognition, how we learn about things and how we make a “read” of a painting. So, while I wasn’t deliberately setting out to have a painting “read,” I was still thinking about all the layers of perception and cognition that come between you and an object. It’s not a bad thing, and I was trying to understand that at a time where I was actually okay with getting a bad review. It questioned my whole practice, which is really just about day-to-day life. What do I experience every day and what drives me? How does language help me or become an obstacle? The “Love your work” phrase is something that I’d heard for years, and I think it’s still in play. It’s one of the most awkward phrases to use because if you’re the one saying it—often you’re called upon to say something—it’s not that it’s necessarily insincere, but it’s sufficient only for the moment, when you can’t think of anything better to say.

BRARA: The work is also said to be a reflection on the accumulation of taste, and I was wondering what you thought about taste in the art world. Should we constantly be talking about it, or do you think we should it keep to ourselves?

FEINSTEIN: I think with regards to taste, it’s really about how you make your own taste and what your criterion is. Even if you decide to use a blank page, it’s still a signifier of your taste and therefore a projection of you. To me, it’s an awareness of the urgency of a particular social condition that creates taste. I was at this conference in Knoxville recently, and I was thinking of how my work is kind of an exchange between old media and new media, and what the difference is between aesthetics and technology-based work. And that intersection is really what I’m interested in, in how technology becomes part of taste, and how it informs different definitions of taste today.

BRARA: Yeah, I think technology definitely blurs the lines between categories of taste. Because we have access to everything, it’s really easy to quickly “acquire” or fake a particular kind of taste that you want to claim as your own. You also mentioned that you were interested in the form of how these messages are presented, and in Love Vibe you chose to use a speech bubble. I was thinking that you could have used quotation marks instead, but that probably would have conveyed a much more punctuated message. The speech bubble is suggestive of a satire, but it’s not necessarily telling you how to interpret the phrase.

FEINSTEIN: I was thinking of it coming from a comic book. In a comic book, the bubble is attached to the character speaking—they can’t go back on what they said. I think if I used quotes or any other kind of punctuation for the work, it would be suggesting a linguistic structure outside of that particular phrase. It wouldn’t be as “spoken,” and would perhaps signify a kind of assigned meaning, which is exactly what I’m questioning the existence of. With the speech bubble, there’s a certain emptiness there, which sort of captures the sentiment I have towards that phrase. It’s unreadable, it can only be deconstructed by the person using it, and because of that you don’t know what’s really being said.

BRARA: And in that way, the bubble emphasizes the emptiness of the phrase by placing it in an equally empty visual form. I would love to observe people at the opening and listen to what they say aloud, and to you, when they’re looking at it. Are they allowed to say, “Love your work?” What does your work prescribe as the right way to praise art, if at all?

FEINSTEIN: I think I’d prefer “No comment.” [laughs] Artists get it. But, for everyone else, I’m really interested to see how they react, and if they get it, too. I love that the phrase hasn’t gone away, so I’m curious about how it’s used now. I also wonder how people will interpret the rest of the painting. I started this piece in 2000 when blue screen was what was most widely used, and now there’s this dominance of the green screen in everything. Because the work is comprised of these large expanses of green, will people think it’s a commentary on digital projections? It’ll be interesting to see how it’s read today.

BRARA: Why did you pick the color green?

FEINSTEIN: At the time, I was motivated by the idea of a fully saturated outdoor space. I was interested in nature, and the idea of landscapes without any other form of life—what you’re left with is just green. And as a paint color, for something that indicates outside while you’re inside, the experience of looking at it in a room was really interesting to me. The green doesn’t vary—I wanted this uninterrupted, matte effect, without oily or yielding surfaces. So, it depicts painting, and the purest form of that, but then with the phrase, it also feels like your reading. Altogether, it’s visually a very straightforward way of presenting an inquiry. No distractions or hiding places.

BRARA: “Love your work” is an example of codified language, and I know that’s also been an important trope in your previous work. Can codified language be deconstructed when ambiguity is so deeply embedded in its use? What, then, are you left with?

FEINSTEIN: I’m not sure if it’s possible, but I keep trying. The word “love” for example—just there. That, for me, has been really, really rich. Because love is not quantifiable, and it’s used as an expression of taste. It’s used affectively. It’s used in intimate language and in public speech. I think part of what I’m supposed to be doing, as the artist, if I use a word like “love,” is to use it in relation to an object or person so that it may be displaced by establishing a connection to something. And that maybe in that process, the encoding—which I don’t think you can ever fully break down—becomes a little more legible. I love malleable messages like that. It’s a constant question, and it really makes you think.

“LOVE VIBE” IS ON VIEW AT ON STELLAR RAYS GALLERY STARTING TOMORROW, APRIL 10, THROUGH MAY 11.