STUDIO VISIT

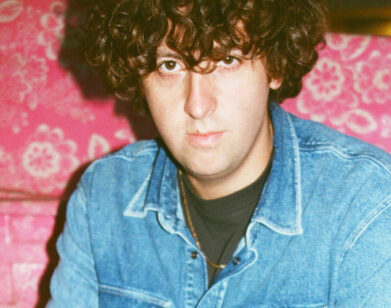

Robert Roest on Idols, Angels, and the Anthropocene

I received an invitation to speak with Dutch painter Robert Roest about his exhibition at EUROPA, Eight Paintings Proving Angels Are Really Watching Over Us, somewhat out of the blue. I had never met Roest and was unfamiliar with his work. My initial reflex was to say a grateful no, only because I had promised myself to carve out time and energy to finish a novel. But then I opened the link to the paintings and laughed out loud at my desk; if my book is ever, in fact, a book, there probably could not be a more on-the-nose image for the cover than one of Roest’s angels. Then I read a bit about some of the thinking and reading that has informed his work and it was almost uncannily aligned with the thinking and reading informing my own. I asked the gallery if they invited me because they knew the nature of what I was working on—this seemed unlikely considering I had only told a few friends—and they said they had not.

So, for reasons both cosmic and editorial, I am tempted to view the serendipitous occurrence of this conversation a little like the scenes of Roest’s paintings themselves: totally explicable, unextraordinary, and mundane and yet—if one would like to conceive of the universe as more than a place of total randomness and entropy—meaningful, the stuff of “signs.” Roest and I spoke at EUROPA in late January, surrounded by angels.

———

GIDEON JACOBS: How do you react to moments in your life in which the universe arranges itself in a way that can feel like a “sign,” or synchronicity?

ROBERT ROEST: The universe can seem something like that, part of a narrative and you are woven into. And that is a tremendous, amazing feeling. Some people have that sometimes, maybe all people, but when such a thing happens, I’m very happy and I dive into it and I take it. But I also know that it could be, another time, the other way around. I used to hold onto such grand narratives that stitched everything together, that the universe aligns itself or whatever you call it. That’s as if something is meant to be, as if the universe had you personally in mind. I have thought a lot about meaning. In some circles some people say there is a “meaning crisis.” Have you heard of this term?

JACOBS: Yeah. Personally, I see it more as an image crisis. I think we are living entirely in the realm of arrows, as opposed to spending some of our lives in the realm the arrows are pointing to. So, if there’s a void of meaning—clearly things are pretty weird out there these days—I think it starts with images and the problem of how we relate to them.

ROEST: How do you see that as an image problem? I don’t think you mean, literally, images. Is it only paintings and photographs or do you extend images also to concepts and ideas?

JACOBS: Yes, absolutely. I was talking to my friend about this talk and told her, “I’m worried I’m just going to end up ranting about spirituality and god when we were trying to talk about art.”

ROEST: Fine with me.

JACOBS: Okay, well then, my personal perspective on this is that—take, for example, The Fall in Genesis. After the apple is eaten, Adam and Eve become aware of their nakedness. They become self-conscious. What is self-consciousness? It is essentially an “I” becoming aware of a “me.” It is the development of self-image. This is intrinsic to our species. Our ability to abstractify reality both knocked us out of the garden and made us who we are.

ROEST: I’d rather see myself naked than be walking around not knowing I’m naked.

JACOBS: That feels like a blue pill, red pill debate.

ROEST: But I am already thinking, already knowing what it is to be naked. So it’s nonsense to discuss a life of not doing that. I am very happy with The Fall.

JACOBS: Me too.

ROEST: It’s healthy to have some self-awareness and awareness of the world. Sometimes more, sometimes less. And it is also always somewhat fluid, too. It’s not that our awareness is a complete direct reflection of reality out there. It is very much through our perception, the story of how we think about ourselves, what we tell ourselves, and probably more or less what we believe in. It is very much a self-construction. It’s not like a clear mirror into who we really are. I find, with constructions and things that are made up, I have totally no problem with that because this table is also made up. A tree is made up. So if we make up things like paintings or morals or ethics or whatever, it is, to me, as valuable as a tree. We make up things and, as long as they serve some purpose, to me it is irrelevant if nature made up a tree or if we made up a painting.

JACOBS: I agree. I have a love-hate relationship with images. I think about art, write about art. I worked in photography for a while. When I talk about The Fall or the banishment, I am talking about it as myth and story, and to me, it’s an amazing story about the human condition—a condition that, as you said, we can’t put back in the box. We can’t undo any loss of innocence and we shouldn’t want to.

ROEST: No, I don’t want to.

JACOBS: The press release opens with, “For Robert Roest, the act through which sensory information is reproduced, imitated, and transfigured into thought, speech, dreams, images, film, art, writing and so forth, is an evolutionary survival tactic. It creates meaning.” And I wanted to ask a straightforward question: how do you see that as an evolutionary survival tactic?

ROEST: Well, as human beings, we never take in reality as it comes to us. We always have to, in some way, reproduce it in thought, in creating our own narratives. We don’t take in all of reality. We have a representation of all of it. We pick things out almost unconsciously and create some sort of narrative and that’s how we go about things. And in our relationships to other people, we retell experiences we have. Plus, sometimes you have some motivation, say you make the story a little bit nicer, a little bit funnier or a little bit more dramatic. That’s the way we go about things. It seems to we are the only species that does this to survive. I’ve never seen animals copying or mimicking experience, making poems. We are the only species left, as far as we know, that survives by mimicking reality. That is almost the only thing we do. And maybe some people are good at meditation and stuff, trying to empty themselves of all these thoughts. Do you meditate?

JACOBS: Yeah, meditation is an important part of how I have managed to stay alive and live comfortably. At this point in my life, I would describe it as, at its best, a practice of using objects to soften my grip on the realm of objects, or using images to soften my focus on the realm of images. The hope is, if I can soften the grip enough, I begin to vaguely sense what else it might be here: call it soul, god, the divine, whatever you want.

ROEST: The emptying of images.

JACOBS: The sensing of what might be here other than images.

ROEST: But then it’s hard to describe because there are no images to describe it.

JACOBS: That’s the idea. Which leads me to another thing I want to talk about: A lot of my interest in iconography is about iconoclasm and how recently I’ve become interested in the Abrahamic faiths. because of their emphasis on God being formless, not directly imperceivable by nature. Theoretically then, any idol or icon is false.Worshipping anything that can be represented is in idolatry or iconolatry. The second commandment forbids graven images, and really, any image that depicts reality. So the reason why I kind of freaked out when I saw your paintings is that they are—

ROEST: Very idolatrous.

JACOBS: No, no, no. The commandment forbids graven images, those made with human hands. The clouds arranged themselves into the shape of angels all on their own. No human hands. Your angels are exceptions!

ROEST: I would like to say something.

JACOBS: Yes, please.

ROEST: I think something is lost in trying to forbid idols. You have, let’s say, a tribe that still lives in a hunter-gatherer way and they have magical art. Now we totally dissected that stuff so that all of these great idolatrous values or purposes are lost. But let’s say they had some sort of art that was not just meant to be consumed, or to make a house pretty, or to develop an idea that roots them in a narrative. This art is superstitious art, they could use to touch on something that is very real. In the Bible, it says a lot of negative words as if these people were literally worshiping stone and wood. I think they got that wrong. They were touching on some immaterial reality or thing, and fear that sculpture or painting or whatever it was. But the thing is, it seems you cannot have the profit of both thought processes. There is something to say for being aware of images and idolatry, but in the end, these people have an image about god they cannot do without.

JACOBS: I think that is an example of images serving as means to non-imagistic ends, properly functioning as arrows. But as technology gets more advanced and images grow more dynamic, engrossing, and convincing, do you trust our species to not get thoroughly lost in images, slip down that slippery slope?

ROEST: Well, I don’t trust our species and we will surely slip down many slopes.But images and representations—it’s the only way in which we can communicate, with ourselves and other people. So it’s slippery, but it can be an interesting slip, or I guess, or slide.

JACOBS: I like that. The anthropocene as just one long slippery slide.

ROEST: But what you were saying about the emptying of images, maybe that’s also a slippery slope, the end of which is no images. What are we going to do there?

JACOBS: I guess I believe our relationship to images calls for balance and we are living in an imbalanced moment. My last question: I have some sense of why I’m obsessed with this subject, based on my life. Do you have a sense of why you are, given your life?

ROEST: Oh, yeah. That is easy to answer. I had a very religious upbringing and from a very early age, the important questions of life and death were put on a plate for me. And that is intense. They tell you it’s a matter of life and death to explore and you have to write the correct answers. Back then, it gave me anxiety because you had to figure it out. But now I find it very silly to explore these things, these questions of what is true or not.

JACOBS: I agree. This whole conversation has been very silly, in a good way. It’s silly to talk about the efficacy of images using images. It’s silly to talk at all.

ROEST: We’re monkeys going on a rock through a black space. My childhood had a big influence on me, but luckily I don’t think it’s important. It’s more important to drink good coffee or something.