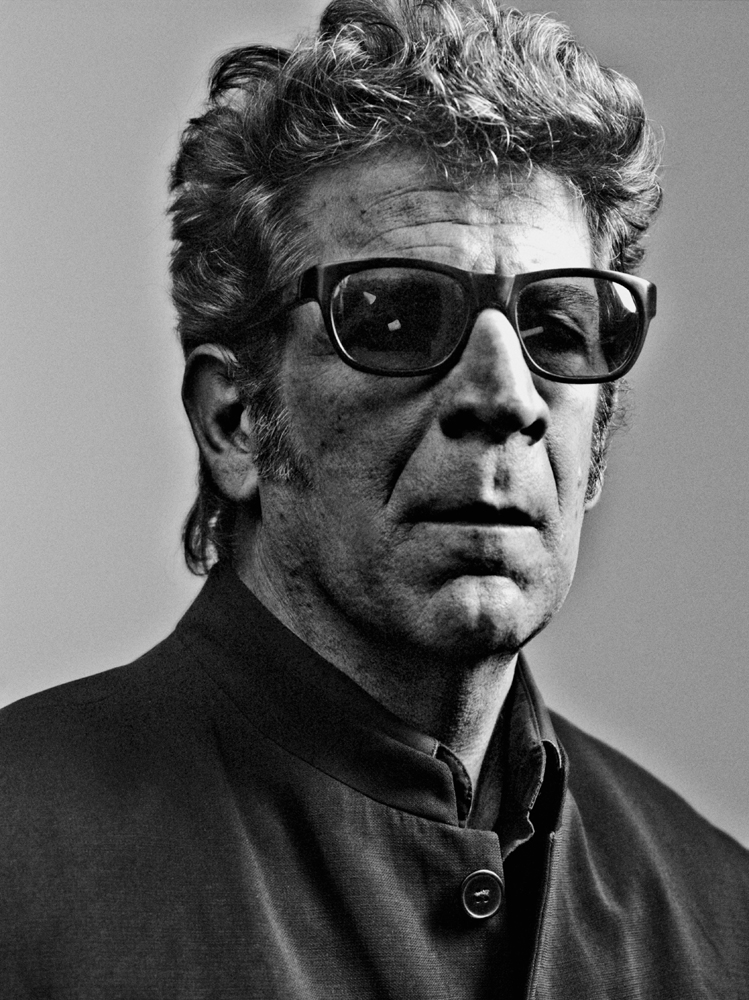

Robert Longo

CHARCOAL IS THIS INCREDIBLY FRAGILE MATERIAL. I’M MAKING IMAGES OF PAINTINGS OUT OF DUST. Robert Longo

Of the contemporary artists who came to prominence in the 1980s and went on to try their hand at filmmaking in the ’90s (among them Julian Schnabel and Cindy Sherman), Robert Longo seems like the perfect fit for the role of Hollywood-style director. His sleek, 1995 sci-fi feature Johnny Mnemonic, starring an already famous Keanu Reeves, was an experimental outgrowth of an aesthetic path that the New York artist had been pursing on paper for more than a decade. Longo is technically a draftsman—his signature large-scale works are amalgams of charcoal on paper, and the tactility of the medium is explicit when faced with the work. But Longo’s productions are arguably much closer to cinema, his chiaroscuro subject matter seemingly created out of shadow and light. And like cinema, Longo’s works straddle a line between hyper-realistic and disturbingly surreal—time is frozen or extended or simply disintegrates, as what happens in his work refuses to resolve. Over the course of his career, 61-year-old Longo has created images of nature (tumbling waves, great white sharks, tigers, flowers), of institutional power structures and political fallout (the U.S. Capitol, the American flag, a fighter pilot mask, the detonation of the atomic bomb), and of personal, psychic spaces (a woman’s chest, a sleeping child, the interiors of Sigmund Freud’s home). He has also created some of the most prescient and haunting images of our age. His twisting, falling business-suit figures from his early-’80s series Men in the Cities became a startlingly accurate artifact of fragility and human suffering after 9/11. (Even Johnny Mnemonic‘s fascination with a future where secrets are impossible to keep seems strangely prescient.) This month Longo takes on an ambitious double-barrel solo show in New York, with his recent series of charcoal drawings that replicate or re-address famous American abstract expressionist works showing at Metro Pictures, while exhibiting an American flag sculpture and work inspired by the riderless horse at John F. Kennedy’s funeral at Petzel Gallery. It’s a dual production that seems to drive straight for the center of American mythology and the coercive symbolism of a cultural superpower. In May, Longo is also being honored by the Kitchen, partially for his curatorial work with the downtown nonprofit in the late ’70s and early ’80s. This past February, his friend and former lead actor, Keanu Reeves, got on the phone with Longo to talk about his obsessions and what keeps him coming back to the surface after diving so deep. —Christopher Bollen

KEANU REEVES: So, Robert, hello!

ROBERT LONGO: Hey, brother. I haven’t talked to you in a while.

REEVES: I know. There’s a lot of water under that bridge.

LONGO: I keep on hearing friends of mine say, “I saw him walking around the street the other day.” I say, “I know. He’s shooting a movie here.”

REEVES: I was working in the city and I could never get away. It was depressing.

LONGO: That’s okay. I’ve been working in the city too. [laughs]

REEVES: Since this is a public conversation—for those of you out there who are not familiar with Robert Longo’s work, please pause and go look at it. Be astounded and inspired and come back. [Longo laughs] Okay, now you’ve checked out Robert Longo’s work. So you’ve got this show coming up; you’re doing new pieces that are a little different.

LONGO: You know, I read recently that Jackson Pollock used to have people like Robert Motherwell write his responses for interviews and stuff like that. I kept thinking, “Who should write mine?” I kept on thinking Louis C.K. or Katt Williams or something. [laughs] Because I’m so immersed in this project right now that it’s a mindfuck for me to talk about it. At Metro Pictures there’s going to be an exhibition of black-and-white, charcoal translations of paintings by 12 abstract expressionist painters, ranging from de Kooning and Pollock to Frankenthaler, Mitchell, and Kline.

REEVES: Fuck yeah.

LONGO: I’m going to show them without the glass, so you really will see the drawings. In a weird way, I keep thinking about McLuhan’s “medium is the message” or something like that. It’s a show about these paintings, but it’s also about drawing. And it’s a really bizarre process of translating them into black and white. What’s really wild is that I got the permission from all the estates to do these drawings.

REEVES: That’s a great nod, to have the respect of these estates. I know that you do that—I’ve seen other pieces where you’ve taken the works of the masters and done these translations.

LONGO: Those I usually just steal. [laughs]

REEVES: Yes, but the quality of the theft, the caliber of the artists you go for …

LONGO: I’m an image thief.

REEVES: Well, it isn’t exactly stolen, but I think that’s a cool nod.

LONGO: It’s bizarre doing this translation thing. I’ve been reading a lot and talking to curators and art historians—I even hired an art historian at one point to work with me. One of the interesting things I discovered is that in the late 19th century, painters actually had black-and-white copies made of their own paintings. They chose it even over photographs because they knew the photographic medium would distort their work. And this translation process becomes a highly subjective thing—turning reds and blues into black-and-whiteness. It’s really bizarre for me.

REEVES: You’re doing some weird archival reclamation process, a simulation reinterpretation.

LONGO: It’s also become a combination of archaeology and forensics. Like, how long does it take to make a brushstroke versus how long does it take to draw a brushstroke? It’s weird making a drawing of painting. I start to realize that charcoal is this incredibly fragile material. I’m making images of paintings out of dust.

REEVES: I know that you have a bunch of art history in that noggin of yours. As you’re trying to re-create these brushstrokes and gestures and curves and straight lines, does it communicate anything to you?

LONGO: Oh, totally. Sometimes it becomes channeling, like, for instance, Joan Mitchell’s painting is so violent. It’s like a knife fight. And you can tell how tall she was. You realize that she didn’t really reach the top of the painting so well, so most of the action is right in the middle. Or you can see that she’s right-handed because the strokes come from the right. You can feel how the strokes go because there’s a weight in the brushstroke where most of the paint starts and it tapers off. You can experience those aspects of it. It’s also weird because the drawing process is so very different than painting. And I’m sort of deconstructing the process of what marks came first, what came later. I’m basically trying to understand abstraction and going back to this point in American history, which is the post-World War II euphoria of leaving behind Europe and trying to be free. Every aspect of the image is interesting to me to dissect and understand.

REEVES: And what’s at the second gallery where you’ll be showing at the same time?

LONGO: That’s Petzel Gallery. It’s a very different show but there is a connection. At Metro Pictures, there will be a small history drawing based off a photograph done by this guy, Russell Rudzwick, who is, like, 72 years old and lives in Queens. He took a photograph of a horse called Black Jack that walked in the procession of JFK’s funeral. Black Jack had a military saddle with riding boots backwards in the stirrups. This image becomes a bridge between the two shows because the abstract expressionist paintings start in 1948 and the last painting is an Ad Reinhardt—a black-on-black painting from 1963. So that’s the connecting bridge. The Petzel show will have a huge, 17-foot-tall, black American flag sculpture that’s embedded in the floor. It looks like a sinking ship, and it’s made out of wood and wax. In another room will be a gigantic drawing of the Capitol, about 40 feet long. And in another will be a detailed drawing of Black Jack’s saddle … It’s very Americana, dare I say. It’s a bit like Moby-Dick, which is something I’ve been really interested in lately. It’s like the flag becomes the Pequod, the Capitol becomes the whale, and the saddle basically becomes the coffin that Ishmael floats on at the very end when the ship sinks.

REEVES: Call me Ishmael.

LONGO: It just hit me today that I’m doing all of this epic stuff at this point in my life. Like my God Machines show [2011, large-scale charcoal drawings of Mecca, St. Peter’s Basilica, and the Wailing Wall]. I’ve been dealing with these epic images, and I realized all of a sudden that I grew up in the age of epics. The movies that really had a huge influence on me were Spartacus or Ben-Hur or Cleopatra or Taras Bulba or The Ten Commandments. You can’t escape your roots.

REEVES: And now it’s not only drawings but also a sculpture.

LONGO: Well, my degree was in sculpture. I always think that drawing is a sculptural process. I always feel like I’m carving the image out rather than painting the image. I’m carving it out with erasers and tools like that. I’ve always had this fondness for sculpture.

REEVES: When was the last time you did a sculpture? I can’t remember.

LONGO: I did them in the ’80s and the ’90s. I think the last really big sculpture I did was that big bullet ball with, like, 18,000 copper and brass bullets on it [Death Star, 1993].

REEVES: That was probably two decades ago, wasn’t it?

LONGO: Yeah. It’s weird to start realizing how many different artists one has been … I’ve been an artist for, like, 37 years.

REEVES: That’s epic!

LONGO: I’m really lucky, man.

REEVES: The installation for two shows at once must be a lot of work.

LONGO: The great thing about doing a show in New York is that you can work until the night before. [laughs] Right now, we’ve just started the Pollock piece, which is totally insane because I figure I’ll finish it right before the show. It’s funny, I found out that Jackson Pollock named one of his dogs Ahab. It’s kind of perfect.

REEVES: The synchronicities keep coming.

LONGO: [laughs] I know.

I FIND THAT ALL OF THESE SUBJECTS THAT I’M DEALING WITH TEND TO LEAD ME TO RELIGION AND POLITICS ONE WAY OR ANOTHER. IT’S NOT SOMETHING THAT I NECESSARILY WANT TO ADDRESS, BUT IT SEEMS LIKE IT’S SCREAMING AT ME TO PAY ATTENTION TO IT. Robert Longo

REEVES: I don’t know if it’s because I’ve worked with you and have been watching closely over the years, and I guess all art is personal in the end, but the themes and periods of your work—the children, the waves, the bombs, the flowers, the God Machines—there seems to be a constant historical perspective to your work. And then there’s also life and death.

LONGO: What else is there?

REEVES: But you also seem to be making intentional conflicts, conversations in conflict. There are always oppositions—ecstasy and pain, power and frailty, historical context and Freud interiors, beauty and death. I think your work wears its heart on its sleeve, as though you look at it and you can get it, or some version of it. It just kind of takes you on this Longo journey.

LONGO: In hindsight, when I look back on everything I’ve done, it all somehow makes sense to me. But it doesn’t make sense when you’re actually doing it. One body of work seems to lead into and inform the next one. I read this great thing that this art historian, Maria Lind, said that art is a form of understanding—like philosophy and science and mathematics are an understanding—but the difference is that art has the capacity to hold all these different things. It is the form of understanding that is best suited for the contemporary time that we live in. In that sense, I think this pursuit of trying to understand things is really a critical issue. I see the issue of life and death in everything I do. I’m trying to find answers. It can be quite frustrating, but at the same time, I’m never quite satisfied with what I’m doing, so I’m always looking for the next thing. The ebb and flow as an artist is a bizarre experience, for sure. I was lucky enough to become successful pretty young—in late ’79, 1980—with a body of work that got recognized and became an archetype. I basically spent so much of my life running away from that Men in the Cities work. I made another body of work, called Combines [1982-88], which was like trying to make movies on a wall and was made up of all different images and materials. I had the aspiration to make movies because I thought that was the cycle. I had this insane egomaniac idea that I could make movies because I made these gigantic art projects. When we made Johnny Mnemonic, it was a rude awakening because I couldn’t control it. That was quite a devastating experience for me. In hindsight, you can always tell the future … On the one hand, it’s like, “Send me back to the studio with my tail between my legs,” and on the other hand, it’s like, “God, I really like being an artist.” The thing that’s interesting as you get older as an artist is that the biggest challenge seems to be: how do you stay relevant?

REEVES: Right.

LONGO: What’s ironic is that now people know my work from the last 10 years and that’s what I’ve become known for. Some of the young guys who work for me now pick up some of the books on my bookshelf and say, “Oh, you’re the guy that made that.” I started realizing I have enough history that some of it has been forgotten. Or if you’re fortunate enough with your history, like with Men in the Cities, your work becomes so absorbed in culture that the authorship of it doesn’t exist anymore. Like, you know, seeing my work ripped off—

REEVES: It’s like, who did you copy those figures from?

LONGO: [laughs] Exactly! I remember when they had this “Pictures” exhibition at the Met [“The Pictures Generation, 1974-1984,” 2009], there were three big Men in the Cities drawings hanging in the lobby, which is incredible. And someone asked me, “Did you get the idea for those drawings from the iPod ad?” [both laugh] No, these drawings were done, like, 30 years before the iPod ads. In that sense, it was kind of like, whoa.

REEVES: I’ve heard you speak about looking at our time and making art in a time. And for these upcoming shows there is a sense of mystery behind both subjects. Abstract expression is so solid, so successful and recognizable, but there’s a mystery about the artists that goes into it, a fetishism about the artists themselves and who they were. And when I think of JFK and the scope of that myth and life, Camelot and the end of innocence, it’s one of the greatest times that also becomes an obsession about the personalities.

LONGO: In doing all this research, I came across things that I probably should’ve known but didn’t about the AbEx guys. So it’s post-World War II and about escaping the idea of composed pictures or attacking a picture, so it becomes more about a performative aspect or recording the performance of the artist. A lot of these guys were leftist and worked in the WPA, and they were also trying to figure out the big dilemma of what their subject matter was. They were interested in the subconscious and in primitive art and things like that. In the late ’50s, the Museum of Modern Art exhibited this work, and basically the abstract expressionists became propaganda funded by the CIA in Europe to kind of perpetuate American values. Modern abstract art starts in Russia in about 1915 with Malevich, and then the Russian Revolution happens, and eventually all that experimental art gets squashed and social realism comes back into play. All of a sudden, Malevich is no longer painting black squares; he’s painting peasants in colorful schmattas.

REEVES: He went to the farm.

LONGO: I find that bizarre that these artists ended up being these kind of tools. But I think a lot about the political situation that we live in now, and I find that all these subjects that I’m dealing with tend to lead me to religion and politics one way or another. It’s not something that I necessarily want to address, but it seems like it’s screaming at me to pay attention to it.

REEVES: An artist can have an intention, but the viewer has their own subjective experience. One of the things I enjoy when I come to your works is the titles you’ve chosen, like Monsters for your waves or Weapons of Mass Destruction for your dollar bills. I like the language, even if it’s technically not part of the picture.

LONGO: That’s why it’s really frustrating. I can’t come up with the titles. [laughs] My wife hates my titles. She doesn’t even want to know about them.

REEVES: [laughs] Like, “Don’t tell me what your art is! Or isn’t!” Does she tell you you’re wrong?

LONGO: No, she just doesn’t like the titles. As an artist—I’m sure like most creative people—you have this kind of board of directors that you make your work for. For instance, you’re one of them. It’s a group of people that you have, these friends, and you want to know what they think. In a weird way, you’re making the work for them. I mean, you make the work for yourself first and the next line is the people you trust, and you know that they’re going to tell you what they feel. They let you know if you’re dishing bullshit or if it’s real. The first person in line for all that stuff is usually Barbara [Sukowa, Longo’s wife]. I count on her gut reactions. They’re always insightful. She’s nervous about saying something, but most of the time she’s right. I say 99 percent of the time she’s on the mark. I feel like she is my great secret weapon in that sense. And then she turned into Hannah Arendt! She became a philosopher.

REEVES: How is it going with your music?

LONGO: It’s been like therapy to be able to play music and not embarrass my children too much. They’ve come to a bunch of the shows. It’s kind of cool. I’m glad they like it. And Barbara is extraordinary when she rocks out. I get to play with all these great musicians and it’s always a little embarrassing for me because of how shitty I am compared to them. But they like playing with me.

REEVES: That’s because you rock, brother.

LONGO: [laughs] We try hard. It’s basically like Tina Turner doing “Proud Mary,” where she would start off slow and quiet, and then she says, “We never, ever, do nothing nice and easy.” That’s what I want on my tombstone.

REEVES: I wanted to ask you about paper—the paper you use for your work. I know you’re pretty particular about it.

LONGO: Well, my factory had changed the manufacturing process of the paper I used for years. It’s not handmade paper. It’s machine-made, archival paper. It’s a kind of cold roll paper. But it’s extraordinary. The paper has a really particular surface on it, and then it was gone, and the replacement paper became much rougher, or artier, for lack of a better term. I finally called the factory up and said, “What’s going on here?” The guy at the factory knew my work and he was really excited that I was using his paper. So he started to make paper for me. Now I buy paper in gigantic rolls. It gets mounted onto these aluminum panels and stuff like that. But it was a bit of a dilemma. Someone once told me that the “implicit horizon” of my work was painting. She was saying that my work evokes painting as much as it evokes cinema. I do have great respect for painting, but I am definitely not a painter right now. I make drawings of paintings, and I’m jealous of painting for sure, but, for me, the paper gives my work a limit. For instance, the Pollock that I’m doing, I can’t get paper as big as the canvas that Pollock used for his paintings, so it has to be made out of three panels that lock together. Or, you saw my work Mecca [Untitled (Mecca), 2010]. Mecca was, like, nine panels. So there are these limitations that I have for sure, and I feel like I’m constantly fighting them.

REEVES: Since this is Interview, I was wondering if you had any New York, ’80s Warhol stories that you wanted to tell?

LONGO: My generation was a real rowdy generation. We were really eager to replace the people before us. When Cindy [Sherman] and I moved to New York, it was, like, 1977. We couldn’t afford to live in SoHo, so we lived down on South Street. We broke up around 1980, but we still stayed close. We had these big parties at my loft after openings. They were filled with lots of rock ‘n’ roll people and lots of artists. I remember being at one end of the loft and somebody came running from the other side saying, “Warhol is at the party!” I remember my immediate reaction was, “He wasn’t invited!” [laughs] Thinking about it now, I’m like, “Whoa, where was my brain at that time?” But that’s how aggressive we were with the idea of trying to replace the people in front of us, for sure.

REEVES: That’s the way it goes. Did you meet him?

LONGO: No, I actually never met him. I actually never had a strong desire to meet him. I loved his work very much, but I had no desire to be a part of any of that stuff. It just never interested me. I guess now they’re not going to run this interview. [both laugh] I never understood how people who met him one time would from then on call him Andy. To me, Warhol was this iconic monument who made extraordinary work. That, to me, was so much more important than any of the rest of it. Did you ever meet Warhol?

REEVES: No, I didn’t.

LONGO: But you met me.

REEVES: [laughs] I certainly did. All right, man, I’ll see you down the road.

LONGO: You need to come by the studio again. We could use another hand drawing.

REEVES: I’ll answer the phone. I’ll get you guys coffee or something.

ACTOR KEANU REEVES’S DIRECTORIAL DEBUT, THE MAN OF TAI CHI, WAS RELEASED IN 2013.