EAT

Rirkrit Tiravanija Introduces Precious Okoyomon To His Chaos Menu

This past summer, at a former car dealership in Hancock, New York, the artist Rirkrit Tiravanija spent the weekend cooking up curry for crowds of hungry art-goers and country neighbors. It’s all part of the upstate art gallery and canteen called Unclebrother, which the artist founded with the gallerist Gavin Brown a decade ago. But it’s also in keeping with the spirit of the Thai artist’s radical, interaction-focused, and food-centric artistic universe, which Tiravanija has explored and expanded ever since he served pad thai and curry to audiences in the early 1990s. It’s a blatant rejection of the market-driven art world system of filling a gallery with sellable work. Tiravanija’s art has always been about creating connections—whether in eating and drinking, or in his text works printed across posters, maps, t-shirts, or ping-pong tables. This fall, New York’s MoMA PS1 will host the first retrospective of the artist’s career, with plenty of curry to go around. But Tiravanija is hardly an artist who dwells in the past. For this interview, he spoke with his friend and fellow foodie, artist Precious Okoyomon, as they prepared and ate dinner at his house in Narrowsburg. It was a chaos menu.

———

WEDNESDAY 6:38 PM AUG. 30 , 2023 NARROWSBURG , NY

RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA: It was a great weekend at Unclebrother, wasn’t it?

PRECIOUS OKOYOMON: I had a lot of fun. I haven’t worked in a restaurant in a long time.

TIRAVANIJA: When were you working in a restaurant?

OKOYOMON: My mom owned the only Nigerian restaurant in Cincinnati. I grew up in a kitchen. Then throughout college in Chicago, I worked at a very fancy restaurant and a gastronomy kitchen.

TIRAVANIJA: Have you watched The Bear? It started out as a sandwich shop, but now, in the second season, it’s becoming more upscale. But they’re keeping their sandwich window to serve their old customers.

OKOYOMON: Oh, that’s cute. When did you start Unclebrother?

TIRAVANIJA: Nine or ten years ago. I was living just a bit up from Hancock, in the woods by the lake. And then Gavin is in Lordville, so Hancock was the middle point. Gavin drove by this garage one day and saw that it was up for sale. So first we bought the garage, and then the greenhouse. We knew we were going to use the space, but we didn’t know if there would be any people. I’m always surprised to see that there are all these people coming. For me it was always a community space, whether the community accepted it or not. That’s why we serve free curry. Everyone can eat, and it doesn’t cost a lot of money to make. A lot of people with money have moved up there since the pandemic, and young people, too. It’s a real mix.

OKOYOMON: I feel like people are really into it in a very earnest way.

TIRAVANIJA: I like how they appreciate it. It takes a lot of energy, even if we just do two nights, because I’m worn out. We’re not really a restaurant. We’re just a kitchen. Okay, I have to make the starter and the salad now.

OKOYOMON: What are you making?

TIRAVANIJA: I have a burrata that has been sitting in the dashi, which is an experiment. Actually, it’s because I was in Singapore, and my friend Jeffrey took me to this tiny local place run by a Japanese man. He basically marinates his mozzarella in miso, which I’m planning to do.

OKOYOMON: Wow. That’s sexy.

TIRAVANIJA: It’s a fermentation thing. You ferment things in a tasty bean paste. So we can have burrata with a smoked duck which is from my local German butcher, over in Pennsylvania.

OKOYOMON: Ooh.

TIRAVANIJA: I didn’t realize that they did that. I was there to buy some steaks, and I saw the smoked duck, so I wanted to try it out. And then we have a mustard green from our local farmer friend, Eugene.

OKOYOMON: Shout-out to Eugene.

TIRAVANIJA: He never charges more than 20 bucks.

OKOYOMON: He has good edible flowers.

TIRAVANIJA: I’m going to make a salad with mustard greens, arugula, and some sprouts with a very simple vinaigrette. Then we’re going to have shiso rice with seaweed, and we have this pork shoulder that has been brined in a kind of apple cider vinegar and Korean plum sauce. It’s been smoking since 11 a.m., and I also put powdered dashi on it. I have no idea what it’s going to taste like, but that’s the test.

OKOYOMON: Who taught you how to cook?

TIRAVANIJA: It’s self-taught, like art. I grew up in my grandmother’s kitchen. She had a restaurant in Thailand, and I would sit around and watch the chefs. So, it’s not so much that I learned how to cook, but I was watching it. Then there’s a traditional Thai toy set that people would sell on the street. It’s a set of miniature clay pots and a little stove that you put charcoal in. I used to cook in those for the kids in the street.

OKOYOMON: You were just giving out free food to the kids?

TIRAVANIJA: I’d cook curry in the pots, with chives and eggs, and give it to the kids. It was like playing kitchen. Then we went to Canada. This was before I even knew anything about art. My grandmother came with us for a break and she would make croissants, which you can’t just throw together. You have to know what you’re doing, how to layer the butter. That was the first time I actually cooked, and the only time I ever cooked with my grandmother.

OKOYOMON: Did your mom cook a lot?

TIRAVANIJA: My mother, who is a dental surgeon, rarely cooks. But whenever she does it’s perfect. But my grandmother was really the cook. The restaurant she had was Thai and intercontinental food. We used to live in that compound with her. Our housekeeper would come to me after school and go, “What do you want to eat today?” And I’d be like, “I want beef tongue.” And then they would bring it from the restaurant. It was like having room service in the house. At one point, I ate beef tongue every day for a year.

OKOYOMON: I love beef tongue. I had a food obsession similar to that as a kid. There’s this Nigerian dish that’s called ponmo, and it’s cow skin. I was addicted to boiled cow skin. You boil it, it gets really rubbery, and then you fry it with a tomato paste stew and spicy gelatin. It’s so good.

TIRAVANIJA: Does it feel the same as pork rinds?

OKOYOMON: No, it’s soft.

TIRAVANIJA: But you would have to take all the hair off.

OKOYOMON: You do. That’s the worst part about ponmo, washing the cow skin. I hated doing it, but that was always my job. If I wanted ponmo, I had to wash the cow skin with a knife in the sink.

TIRAVANIJA: Cooking for me is an instinct, not a learned thing. That’s how I approach making art. There are no set rules.

OKOYOMON: That’s the fun thing about making work. You’re always coming at it from an instinctual place. It always seems so grounded in this memory-love practice, like feeding people. It’s a literal act of love, and there’s a real love in all the work you make. Do you feel that?

TIRAVANIJA: I’m close to the thing that I do. Early on I realized that I should do what is really close to me, which weirdly, was cooking for other people. Because when I went through college, I was making food at home because I was trying to save money. I’d make a pot of curry or whatever, but then you can’t make one portion of curry. You make like 10 portions. So, I’d just call all my friends to come over to eat it. That became a very normal thing. Then at one moment, when I really made the first cooking piece [in 1989], I was walking down West Broadway to go look at this space where this group show was going to be, and I said, “I just have to do what is really close to me.” And then I said, “Oh. Then I’m just going to make curry.” That was the beginning of where things went, one after another.

OKOYOMON: Do you feel like you were making art from a different place before you realized that?

TIRAVANIJA: I was already questioning making art in a kind of “making art” way. But all along I’ve been saying things like, “Oh, I’m making road signs.” And the road sign doesn’t mean that it’s showing you the right way to go. It could be showing you the totally wrong direction. From the beginning, I was always interested in where I was because I didn’t know where I was. I felt like I didn’t have a place, or I didn’t know where to go. So, my art was always about figuring out where I am and where I’m going. Everything is a kind of roadside, a direction, or a way of finding your way.

OKOYOMON: So what are you going to make foodwise at PS1?

TIRAVANIJA: Well, it’s more about the work, because it’s almost impossible to cook live anymore. So I said, “Okay. Then let’s do it as a play.” It’s going to be like a theater play of the cooking.

OKOYOMON: On a set?

TIRAVANIJA: Yep. But things will be cooked on the stage, and there will be people who will be performing as characters. The PS1 show is technically a retrospective but I don’t think about it that way. Let’s say it’s another intersection in the road and people have to stop and wait, look at the lights, and figure out which way to go. So I’m trying to deal with the work in this situation, which will also make it a new experience. Because the conditions of the past are never the same.

OKOYOMON: It’s always changing.

TIRAVANIJA: It’s always changing, so you might as well acknowledge that and build it into the frame, adding a step rather than just standing there as if everything is normal. Also, regulations have changed. Obviously in terms of fire, we have to think of the well-being of the guests, so they don’t get burned. I think it’s better to admit that this is a very different experience from what it was in 1990, rather than pretending it’s the exact same. There are more rules.

OKOYOMON: We don’t always have space to play.

TIRAVANIJA: Sometimes it can be important to have some chaos, but I think that’s how most of us are living and working and dealing with life and making art. It’s not all clean and organized and safe.

OKOYOMON: I don’t think it should be.

TIRAVANIJA: Yeah. It’s about understanding that art isn’t a thing. It may be everything. Or nothing. It’s just that we tend to think of art as a thing.

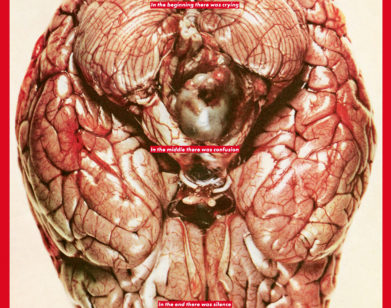

OKOYOMON: It’s literally all the stuff that’s out there and in here, and also not. It’s the cosmic chaos. Not just the white cube, but memory. I feel like you carry that poetic insight of everything, and it leaks into everything you do. It’s infectious. It’s also the way you interact with people. Do you feel like that’s been seeded in you from the way that you are in the world?

TIRAVANIJA: Yeah, I think parts of my grandmother seeped into me. She was always super open and generous, and she went bankrupt because of that. I have always said I would just die in the gutter if it came to doing what I want. It’s fine. I tell my students: If you can say that, then you don’t have to worry about anything because in the end, it will all be fine.

OKOYOMON: To know yourself is a power.

TIRAVANIJA: What do you think about this wine?

OKOYOMON: It’s pretty good. Do you believe in destiny?

TIRAVANIJA: In a weird kind of back-assed way, yes. We’re not all here out of coincidence.

OKOYOMON: I feel the same.

TIRAVANIJA: It’s a kind of Buddhistic thing. Which is to say, everything has a reason and the reason is always going to happen. And for me, maybe it’s about degrees of use, or usefulness. I walked down the street in the East Village and people would smile at me, people I don’t know. I always think it’s so beautiful for people to acknowledge you without ever knowing why.

OKOYOMON: Maybe there’s a cosmic energy. People just want to smile at you.

TIRAVANIJA: I hope. I remember people I saw for two minutes on the street and I see them again three hours later on the subway.

OKOYOMON: You’re really good at witnessing people. It’s a gift you have.

TIRAVANIJA: That’s my next show, me just smiling, walking around.

OKOYOMON: Tell me what you love.

TIRAVANIJA: Let’s just say this, I loved COVID.

OKOYOMON: Because you got to stay at home?

TIRAVANIJA: Because everybody had to stop. It made the whole world stand still, and you had to scale your life to things that were close. I’m not against progress, but I’m in favor of slowing down. Progress should have been about free time, and not about no time. And now the whole social media structure is about no time, because you’re basically always on it. I love not having to do anything.

OKOYOMON: My vibe. I want that for you.

TIRAVANIJA: But not having to do anything doesn’t mean that you don’t do anything. Alright, I’m going to make the second course now.

———

NAM PLA ICE CREAM

by Rirkrit Tiravanija

- 1.5 l thick cream

- 0.5 l milk

- 300 g sugar

- 300 g egg yolks

- Fish sauce to taste

Combine eggs and sugar, stir in cream and milk. Heat the mixture gently until 82 Celsius, can be done in bain-marie. Then pour in a bowl on ice to cool down. When cold add fish sauce to taste. Churn in an ice cream machine.

———