Richard Hawkins and Xavier Dolan On Sex, Violence, and Celebrity Worship

Richard Hawkins moved out of Texas for art school in Los Angeles in 1986. Then, after a few years of writing experimental fiction (among other illicit experimentations), he began a career in art that would contain all of American culture in its erotic death grip. Hawkins’s work runs through all manner of mediums—painting, collage, ceramics, sculpture, table installations, scrapbooks, binders, and zines—and yet his obsession seems almost pure: beauty, lust, wanting, and hunger in all of its classical and rabidly contemporary molds. The 59-year-old provocateur might be the most devious fanboy in the art world. Collages and paintings are chock-full of shirtless teenage idol pinups, from vintage ’70s Matt Dillon to Photoshopped nudes of a leather-harnessed Justin Bieber. (Other recurring stars/victims include Nick Jonas, Leif Garrett, Adam Driver, and Tom Cruise, cut from magazines such as Teen Beat, Blueboy, and Interview, like one long angst-ridden pop-culture wet dream.) Mixed into the visual fray are images of young porn stars and hustlers, horror movie monsters, Greek statues, newspaper clippings of serial killers, decapitated heads, and red paint and ink splattered like blood. Hawkins’s art draws us into a haunting vortex where wholesome idealism, potent sexual subversion, and violent putrefaction meet. It’s as if his real artistry is scattering our brain’s ability to achieve simple, thoughtless wish-fulfillment. Some of Hawkins’s works could be written off as grisly nightmares, except there is so much fantasy seduction, happiness, and delight going on inside their frames. Sometimes I wonder what straight people make of them. They seem to me like perfect gay psychograms. It’s no surprise that Hawkins thinks of his work as semi auto-biographical; a tour through his scrappy, lo-fi, media-obsessed, celebrity-icon–ridden works from the early 1990s makes it clear that he has been a key inspiration to generations of young artists who have taken his punk aesthetic to heart.

As a painter, Hawkins often swims in a different direction—mining art history and the style and palette of painters such as Picasso, Van Gogh, and Otto Dix to create, as he has over the past two decades, surrealist, tragicomic scenes of gay cruising zones and exotic hustler bars. He also mines literature for inspiration, character cameos, and excerpts of text inserted directly into his can-vases. Hawkins has been working in his Melrose Hill studio in East Hollywood on a series of acrylic-on-panel paintings to be shown this summer at Galerie Buchholz in Cologne. These brightly colored stews contain a constellation of nubile celebrity hunks, Death in Venice’s Gustav von Aschenbach as played by Dirk Bogarde, and snippets of poetry from the decadent Victorian writer (and purported algolagniac) Algernon Charles Swinburne. Last February, he got on the phone with the filmmaker Xavier Dolan to discuss art, devouring boys, and desire. — CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

–––

XAVIER DOLAN: Diving into your work, I see a lot of interests and themes we have in common, like the bewitchment of youth and toxic beauty.

RICHARD HAWKINS: And armpits!

DOLAN: Oh yes, armpits, absolutely. But it’s fascinating to find myself in your work as an artist and as a gay man and as a human being.

HAWKINS: We can make this mutually flattering because that’s how I feel about your films. I watched The Death and Life of John F. Donovan last night and there’s that scene where the journalist is resistant to interviewing an actor because they won’t be discussing earth-shattering things in the face of global crisis and inequality. I sort of feel that way, like I’m on a subjective trip and I’m not sure that it makes any difference in some wider world beyond my own little privileged corner.

DOLAN: Don’t people think of your work as political? It obviously engages with queer politics.

HAWKINS: Yeah. The world just seems more hectic than it used to be when you get beyond the age of 50. During the height of the AIDS crisis, which is when I was probably your age, there was a kind of mandate on making political work, because if you were just expressing yourself or trying to make art, then it was this idea of, “This is war, what are you doing?” And I was like, “Well, I want to be an artist. Sorry.” I think that attitude continues today. I teach and see it a lot in grad schools. Everyone wants to be socially engaged.

DOLAN: When I tell a love story between two best friends, I know it will have a meaning to certain youths out there who will watch that movie. Maybe that film won’t change the world, but it might add meaning to their incomprehensible sexuality. And that is already a start. But just to say in advance, I’m not an art critic.

HAWKINS: But that’s the same as my relationship to your films, more emotional and personal than academic. I know nothing about film, even though I’ve watched a lot of them. Take, for instance, your film Tom at the Farm. I know what it’s like to be rural. The dead kid’s life seems relatively similar to my own growing up in rural Texas, identifying as creative and having the need to move away.

DOLAN: Did you enjoy being a teenager in a small town in Texas?

HAWKINS: I think your characters sum that up better than I could. I expect my mother will read this article, so I’m probably not going to tell you how bad it was. But for somebody as sensitive as myself, it was pretty difficult. There was no role model. There was no creative outlet. Do you know this painter Forrest Bess? He died in the ’70s, but he was an eccentric Texan who lived even further out than I did, as a bait fisherman. He made abstract paintings that got him a shake at a career in the New York art world. He was out as a gay man and corresponded with Carl Jung about his theories on alchemy and personal anatomy. Eventually he ended up committing a kind of self-surgery on his penis to make himself into a pseudo-hermaphrodite. Not thatI’m going to chop off my penis anytime soon but…

DOLAN: Please don’t. I wouldn’t recommend it.

HAWKINS: Wait, where was I going with that story? Should we just end here?

DOLAN: Yes, thank you for your time. [Laughs]

“Secret Passage 6,” 2019 by Richard Hawkins

HAWKINS: You know, I was Googling you and I found a gif that was from your film Elephant Song of these photos found in the doctor’s drawer. In this gif your head was on these nudes. They’d obviously been Photoshopped.

DOLAN: I’m sure they were poorly executed. I’m going to Google that scene. Ha, this is weird. “How did your interview go?” “Well, I ended up googling Xavier Dolan, Elephant Song, dick pics.”

HAWKINS: I could tell it wasn’t you because the body didn’t have any tattoos. Maybe it’s Taylor Kitsch’s body? But that’s my favorite kind of celebrity nude. Someone so urgently needed to get off that it doesn’t even look the least bit realistic. It’s just a head stuck on a body.

DOLAN: Yes, those are not about realism. Talking about these collaged celebrity nude photos, I’m curious about the actors who regularly appear in your work. There’s Justin Bieber, sometimes obviously Photoshopped onto someone else’s body. There’s Matt Dillon, Nick Jonas, Adam Driver. How do you choose these muses?

HAWKINS: It’s like casting to some extent.

DOLANS: But what draws you to that particular kind of beauty? Is it their masculinity? The inaccessibility of their bodies? I’m interested in your casting process.

HAWKINS: The inaccessibility is apart of it. That’s always the fan’s relationship to the ideal, to the celebrity. I’m kind of a mean fan. When I collected celebrity autographs, it was a little bit mean. I got Rob Lowe’s signature on a copy of Psychopathia Sexualis [by Richard Freiherr von Krafft Ebing] right after that blow job video came out. Also, I do have a rule against blue eyes.

DOLAN: I was just looking at Taylor Kitsch’s eyes. They are green, so he’s legit.

HAWKINS: I will do green-hazel. But I’ll always change blue eyes for the paintings. I don’t really know why. If I knew, maybe the work would stop. I’ve kind of suspended myself critically and let some of the unconscious things come out in the act of choosing a cast. I’ve yet to figure out what that type is. It’s more the old gods-and-monsters dynamic, or the fetish, as I read you once saying in an interview, for the guy that’s going to mistreat you. It can be self-imposed. This way, I can remain alone with my own suffering. I’ve been thinking about Proust lately, and how [his character] Albertine creates that luscious suffering that he needs in order for the novel to progress.

DOLAN: It seems to me your work is really about desire.

HAWKINS: Oh, definitely.

DOLAN: Obsessive sexual desire for Hollywood, pinups, porn, and murderous fuckboys. But it is a fantasy, right?

HAWKINS: Yes, but I do remember collecting Teen Beat magazines contrary to my gender in Texas when I was 12 or 13 or something. There was something about a fantasized universe beyond what was around me, like football and the threat of exposure and all kinds of other things. I could relax into the world of magazines where the boys in Teen Beat would write I-love-my-fans kinds of things. I had this emotional relationship that was a prepubescent kind of eroticism. No suffering. Surely you had that kind of relationship with Leonardo DiCaprio when you were young? Wasn’t that erotically tinged?

DOLAN: Yes, I did, when I saw Titanic. I remember having very specific memories of how it all happened and what I was wearing. I was with my mom, and I don’t go to the movies with my mom a lot. Truly, I think I’ve been to the movies with my mother six, maybe seven times. But I have very clear memories of whenI saw Titanic and the shock of discovering Leo and understanding my attraction not only to him, but to men. For me, it was really about these TV shows that I watched on the WB, like Roswell and Smallville and Buffy—all these teenage dramas. And it was all about these all-American, bomber jacket–wearing dudes.

HAWKINS: I wonder if that was your kind of coming out to your mother, having her witness what you desire.

DOLAN: I was also incredibly drawn to Kate Winslet, and I did a lot of drawings of her and the costumes she was wearing. That was probably a very clear indication of my homosexuality.

HAWKINS: The repressed dress designer in you.

DOLAN: Yeah, well, I also dressed in my mother’s clothes, so I don’t think she needed Leo to understand the mystery. By the way, I should send you a photo of what I’m wearing right now.

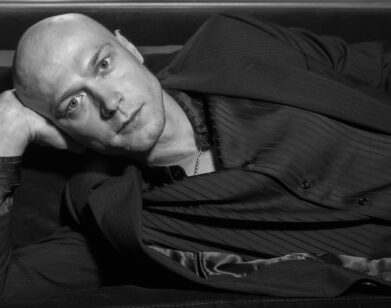

“To Divide Him Vein by Vein,” 2020 by Richard Hawkins

HAWKINS: I have a celebrity anecdote of Leonardo from the early ’90s when I was in some kind of goth-metal phase, probably in my late 20s or something. My room was eggplant purple and it had these black spiderweb curtains overlooking a courtyard. At that point, my hair was dyed black, I wore a wife beater with a padlock and chain around my neck, I was thin as a rail and pale as Morticia, and I heard something outside so I went to the window and there were two boys and a woman standing outside underneath this big avocado tree. One of the avocados fell, causing the boys to lookup at my window, and there were these eyes looking like, “What sort of Flowers in the Attic ghost girl is this?” It was Leo, shopping for a house with his mom. He jumped back, spit the gum out of his mouth, dropped his Game Boy on the ground, and started running.

DOLAN: I think we tend to choose something similar in a muse. I don’t know what exactly it is, but it’s this inaccessible masculine thing. Maybe it’s the fact that I don’t find myself very masculine, so I’m looking for something overly masculine in a muse. But do you think beauty is toxic? Is there a message in your art of beauty that’s ensnaring or violent, that the world might be better without it?

HAWKINS: Certainly not that last part. I think it might be toxic for me, given my insecurities. I would identify the hunk, if you want to call him that, as healthy and bright and irrepressible. And then I always cast myself as a dark, sickly romantic. And it’s not following the old equation of beautiful as dumb.

DOLAN: As you were talking about before with Teen Beat, there’s a sense of childhood nostalgia in your paintings and collages. On my end, I’m constantly revisiting the colors and textures and odors of my childhood as I mature. When I was young, the grass felt really green and the sky looked so much bluer than it does now. I know I’m a nostalgic person. Are you?

HAWKINS: I guess, but at that same time I’m always imagining a future that I haven’t yet reached. In earlier versions of these paintings thatI’m doing now, there were lots of Hollywood or Universal Studios monsters. It was a push-and-pull between these cannibalizing monsters and these youths. But then I put in [Gustav von] Aschenbach from Death in Venice and a couple of characters like that, so maybe I’m looking toward a certain kind of dignity in this dark, sickly romantic first-person narrator. So yeah, maybe I’m imagining a future full of dignity but that’s really swirling in the patterns of the past or something.

DOLAN: In a sense, it’s like an inverted nostalgia.

HAWKINS: Or a corrected nostalgia. Or a fantasized nostalgia. I’ve been in therapy for a long time and I’ve been examining the self, or ideas about when a person gets rid of their homophobia. Do you suck a dick one day and the next day you wake up and you’re totally free of homophobia? I think that’s the kind of baggage that you carry along with you despite yourself and that you can’t get rid of, that you’re always reinvestigating. Everything I make is semi-autobiographical. But it’s also rearranging things, hoping for an evolution to something different. Anyway, did you want to send me that photo of what you’re wearing?

DOLAN: Okay, let me take the picture. I want to hear your reaction now because of what we’ve discussed.

HAWKINS: Are you sure? You have to regard your privacy, you realize, because I’m obviously one of the sketchiest fans in the world.

DOLAN: This is probably going to end up in a collage somewhere. But it’s not a dick pic! What’s your number? [Hawkins and Dolan exchange numbers and Dolan sends picture.] Do you see? I’m the only person on earth who would actually make a hoodie like this. It reads, “Married to Leo Since 1995.” And then that’s Leo on it with good hair. Titanic hair.

HAWKINS: That’s Gilbert Grape Leo.

DOLAN: A finger in a slightly open mouth, serving us a sultry accessibility look.

HAWKINS: And you’re wearing none of your mother’s clothes in the photo.

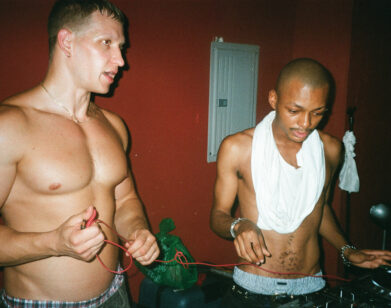

From left “The Collage Killer #1,” 2018, “The Collage Killer #7,” 2018, “The Collage Killer #4,” 2018, “The Collage Killer #10,” 2018 by Richard Hawkins

DOLAN: [Laughs] You said your work is semi-autobiographical. But there’s a lot of violence in some of your paintings and collages. What’s that about?

HAWKINS: I’m involved in self-analysis, knowing how cruel to oneself a person can usually be. And the work takes minor characteristics that I see in myself and blows them out of proportion. The blood and guts and terror and everything else is this subconscious pool of stuff where everything’s not just bright and rosy but is also just the most abject crap. We aren’t organized. We’re social beings but we’re not organized into definite rights and wrongs. It’s like in your film Tom at the Farm. I very easily understand the brother’s homophobia, as well as his tentative homosexual desire and the incest involved in that. That’s what makes it interesting. If Tom had gone home and met a completely different kind of brother, who was just like, “Yeah, we know he’s gay,everything’s fine,” it wouldn’t have the same tension. And in the same way, I think I’m always introducing these abject elements into the work to talk about self-doubt or one’s internalized homophobia. Or the difficulty that one has in accessing dignity in the face of desire. Otherwise, I suppose I could do fairly realistic portraits of celebrities and leave it at that. Then I would be the perfectly socialized artist to the stars.

DOLAN: I, too, am attracted to the monstrosity of beauty. Or at least, I find beauty is most attractive and appealing when it’s flawed and imperfect and brutal.

HAWKINS: I always use my handy analogy—emphasis on anal—that comes from a French post-Freudian feminist psychoanalyst in London. She was interested in the infant’s preverbal relationship to the mother, since everybody else doesn’t really exist before the mother exists. The infant faces the breast and adores it. It’s this thing from which all pleasure and nurture comes. But then the infant realizes that it also had a tendency to go away, which puts you in a traumatic state. Please, Melanie Klein experts, forgive this paraphrasing. The infant also realizes that the breast is the enemy—that it’s always going away and not always there. So, instead of adoring and worshiping the breast, the infant wants to destroy it. That’s the ambivalence that perhaps you and I see in celebrities. Or what you saw in Leo and what I tended to see throughout my entire life in a whole cadre of young hunks. There are both motivations at work: to adore and to absolutely rip it to shreds.