IN CONVERSATION

Rafik Greiss and Rose Salane on Nostalgia, Transcendence, and Revolution

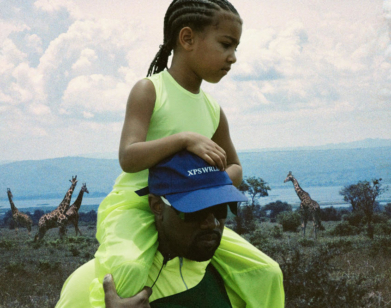

Rafik Greiss, photographed by Zora Sicher.

In The Longest Sleep, a new exhibition by Rafik Greiss now on view at Balice Hertling in Paris, the artist finds himself concerned with the life cycle of objects and rituals carried out across different global cultures. The work spans a number of mediums, including photo, sculpture and video, the latter working as the show’s anchor (its titular short film, shot during Greiss’ recent summer trip to his native Egypt, plays on a loop in the gallery’s basement). To make it, Greiss followed a friend on a whim to a Mawlid, a festival that takes place on the anniversary of a Sufi saint’s death. He found him surrounded by swarms of people undergoing hallucinatory, spiritual transformations, dancing, chanting and swirling on the streets of Cairo. “I’ve never seen this kind of transcendental experience without drugs and just through belief,” the Irish-born Egyptian artist explained. “I thought that was so contagious and it should be documented.” To mark the show’s opening, Greiss sat down with his friend and fellow artist Rose Salane to talk about performance across cultures, Monet’s Water Lilies, and the repurposing of found objects.

———

ROSE SALANE: Hi, how are you doing?

RAFIK GREISS: I’m good. Where are you these days?

SALANE: I’m in New York. Where are you?

GREISS: I’m in Paris.

SALANE: I remember the last time we saw each other was in Paris, in June. You and I were walking from seeing the Water Lilies.

GREISS: Oh, yeah. That was the last time we saw each other.

SALANE: I never saw that room that Monet specifically made the Water Lilies for, and that’s why I was so happy to go see that. I remember you and I were talking about his attempt to have no horizon and, through the paintings, suggest an environment that’s presented without interruption.

GREISS: I think that every artist attempts to create a space where they have a full, uninterrupted narrative over the viewer’s gaze. You also can’t really show the whole as the whole; you have to show it in fragments, and I think he does that really well.

Exhibition view, Rafik Greiss, The Longest Sleep, 2024, Paris, Balice Hertling.

SALANE: Yeah. It’s crazy to say but, conceptually, I see some similarities in your work to Monet’s in how and where the viewer is positioned to look. I remember you telling me about your exhibition and the way that it’s sort of delineated and then regrouped.

GREISS: Basically, I find an experience that affects me and then make work about that experience to recreate it for the viewer. So this show is comprised of many different kinds of work, from sculptures and photographs and video to the combination of all the mediums. There’s work I made in Georgia during my residency there last year, work I made this summer in Egypt, work I made in Paris.

SALANE: Just after I saw you in Paris, I actually went to Cairo and it significantly changed my life. It’s interesting also that you and I come from these extremely chaotic cities. Cairo chaos is much different from New York chaos. But I think it’s interesting because you’re making work in these places, and I’m interested in how you deal with, let’s say, the periphery and action and time within the periphery. I know that sounds a bit abstract, but in cities, I feel like there’s so much happening around us. And as artists, we keep pulling from these things that are in our surroundings and pushing it into the foreground.

GREISS: Totally. Having lived in both New York and Cairo, I think people perceive time really differently in both places, even though they’re both really chaotic. In New York, or in the West even, people perceive time in such a linear way, and they always ask themselves, “What’s next? How do I make a name for myself before I die?”

SALANE: Also, it’s all about the work day. It’s all about the nine-to-five.

GREISS: Yeah. Thinking of time in a cycle made sense in pre-modern societies, where there were much fewer innovations across generations and people lived really similarly to their grandparents and their great-grandparents. Meaning could therefore only be found in embracing the cycle of life and death and playing your part in that as best as you could. That’s why in Egypt, there’s kind of no traffic lights. The relationships between people are really raw and it’s a totally different way of being, I think.

Tskaltubo I, 2024, Inkjet Print on Japanese Paper, 35 x 23 cm, 13 3/4 x 9 in.

SALANE: Yeah, I also know that the ritual and religious ceremonies are so important to the city’s infrastructural identity with the mosques and people pulling out the prayer rugs and having them very handy. I remember I was in the museum and there was a stack of prayer rugs in the corner, and people praying multiple times a day and having a small space to do that in.

GREISS: Yeah, totally.

SALANE: It’s that ritual and that recurrence of positioning your body into different movements. The identity of the city is very much shaped by that, and it’s in my periphery. I really want to hear about this aspect of your show where you’ve documented this ritual, religious ceremony in love.

GREISS: Well, I spent this summer there, and I actually didn’t really know what I wanted to do for this exhibition yet, so I followed a friend to this Mawlid, which is basically a festival commemorated on the anniversary of a Sufi saint’s death. It’s the day a saint was born for the heavens, they say. So the Sufi followers spend their time in big circles. They listen to songs and chants and whirl around while being wrapped in these spiritual revelations. I’ve never really seen anything like it, even though I grew up in Cairo. It was crazy to see the way people were dancing and whirling and their eyes were rolling behind their heads and spit was flying out their mouths, and they were really leaving their bodies in a way. I’ve never seen this kind of transcendental experience without drugs and just through belief, and I thought that was so contagious and it should be documented. So I spent the summer filming these events. It was really hard, actually, because they were not really allowing me to film any of this, so I had to get to know people and spend a lot of time with them before they got comfortable.

SALANE: That’s so interesting. How long does this ritual last for?

GREISS: It starts at around 10:00 P.M. and it lasts until 9:00 A.M. They go to bed as soon as the sun rises.

SALANE: The video itself is incredibly hypnotic. How did the people allow you to shoot them? They’re allowing you to see this complete vulnerability.

GREISS: Yes, which I think is a two-way street. To be able to film these things, I also have to show a side of myself that’s vulnerable, and that’s the only way you can really connect. It’s very hard because these people are going through a whole private, transcendental experience. In the end, all religions are about finding a sense of belonging in the world, and also about confronting the fear of death, and apparently it’s strong enough to make people reach that state of mind. And working throughout all these different mediums, I find that they’re an extension of each other. I think it’s important not to be really specific when starting a project and pigeonhole yourself in a formulaic way of thought. It’s important to stay as open as possible about your surroundings. I don’t really want to pursue a one-dimensional view in the work. I don’t really make photos thinking about a specific exhibition. When I construct an exhibition, I somehow always happen to find some photos that fit the concept. And I find photo to be a medium that plays with universality in how we collectively perceive our surroundings. Even though maybe we share these experiences together, I won’t necessarily see it in the same way.

Exhibition view, Rafik Greiss, The Longest Sleep, 2024, Paris, Balice Hertling.

SALANE: I wanted to ask about the photograph in the exhibition of a statue that you took in a museum. Can you tell me about that?

GREISS: Yeah. I was walking through the museum in Egypt and I took an image of a statue that was left in the courtyard, and people walk around it and have complete access to touch it. The statue has no head, it’s just a bust, and everything is covered in dust and it’s a total mess. There’s a different relationship that people have with preservation there, and I feel like there’s a certain warmth and rawness, which is a direct translation of the social conventions, but it’s still insane that the whole museum is covered in dust and it’s so unkempt with all these precious artifacts. So I titled the work I Hold My Breath.

SALANE: I love that title because you think of the dust within the museum, and even in Cairo itself. I remember being there in July, so it was very, very hot, and there was so much dust in the city and also coming in from the desert. It’s also an incredible way to connect it to the ritual within the Mawlid video, and just to—

GREISS: Time.

SALANE: Time, and the performative culture.

GREISS: Yeah, it’s really interesting to think of culture as performance, I think. When I moved to New York, I realized there were so many cultures in such a small amount of space.

SALANE: Why did you leave Cairo? And why did you decide to go back more often?

GREISS: Well, I left after the revolution started, which was over 10 years ago. I visit family every year, but I have never lived there or been there for longer than maybe a week at a time.

SALANE: And the revolution started in 2011, right?

GREISS: Yeah. I left in 2013, two years after it started, and my mom actually took me to Tahrir Square to many protests before I left.

SALANE: Oh, wow. And that’s across the street from the Egyptian Museum.

GREISS: Yeah. It was pretty wild to see at such a young age.

I Hold My Breath, 2024, Inkjet Print on Japanese paper, 103 x 66 cm, 40 1/2 x 26 in.

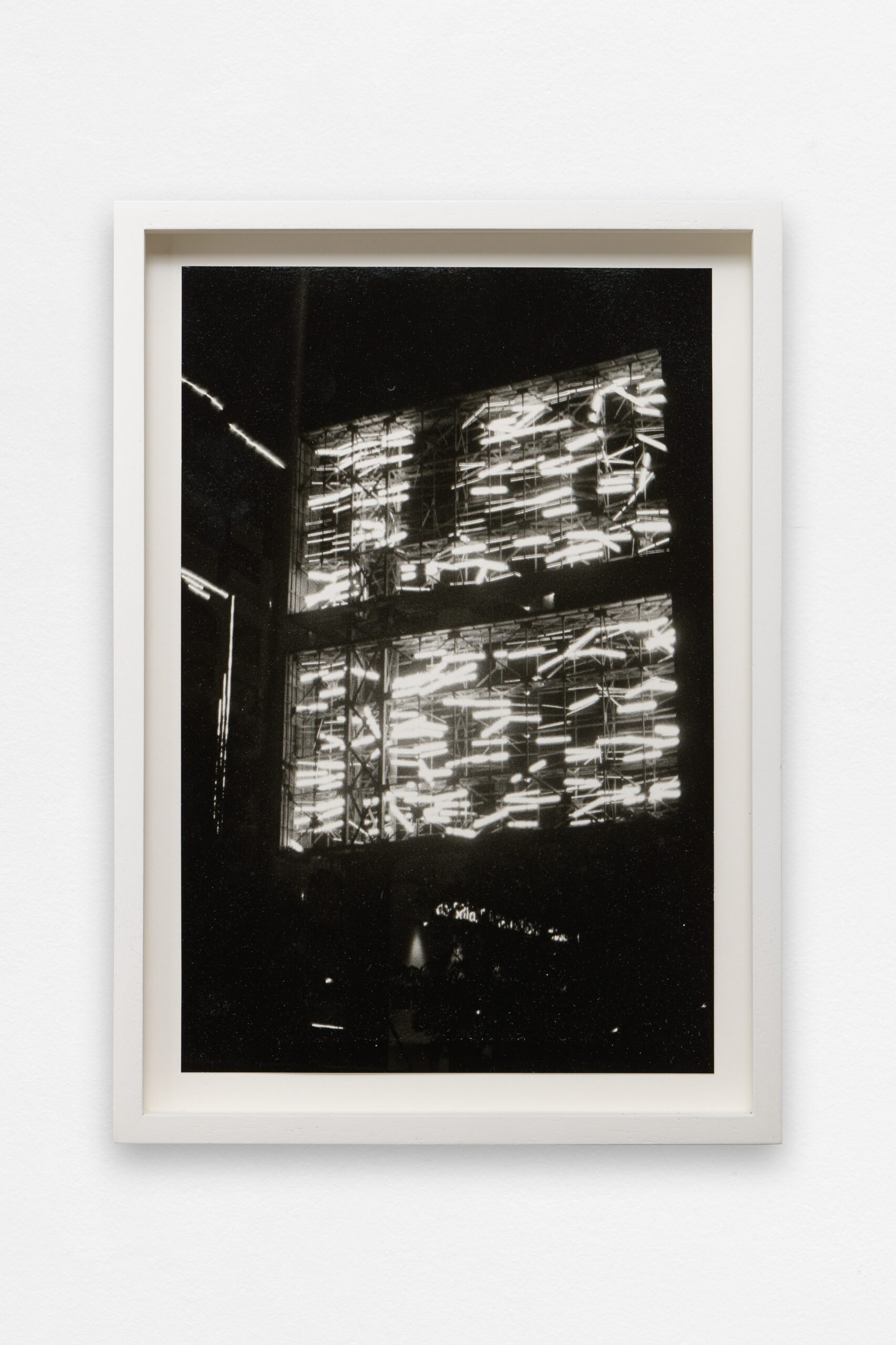

Pattern Recognition I, 2024, Gelatin Silver Print, 30 x 20 cm, 11 3/4 x 7 7/8 in.

SALANE: I remember going to Tahrir Square and it was just incredible to see the amount of space. It’s a huge square, but I’m sure when there’s so many people occupying this space, it must look so different. What was it like seeing all of those demonstrations in Tahrir Square over the years?

GREISS: It was pretty crazy. There were five million people in the street, and it just felt really powerful to be involved in this monumental moment. I was 13, and it was the first time that I saw this collectivity of power being held by the people asking for a change from corruption.

SALANE: That’s such a powerful age to see that at. It’s interesting how this can redefine relationships to a home. I think a lot about what kind of nostalgia is held within countries that have been severely impacted through war or dictatorships. There is this book that I love, actually, called The Future of Nostalgia, by Svetlana Boym, and she addresses these complex social and cultural relationships. She’s interested in nostalgia as a historical emotion and how that feeling can transcend individual psychology.

GREISS: Oh, it’s kind of like a collective experience that affects a whole generation.

SALANE: Yeah, exactly. She discusses the erection of monuments and their presence as remainders of heroes and anti-heroes of a place, and how myths are made possible by fissures of recollection over lifespans and reinterpretations of mass media and popular culture. But I remember she says this really interesting thing about how nostalgia tantalizes us, and it’s about the repetition of the unrepeatable materialization of the immaterial.

GREISS: I feel like nostalgia can be seen as a phantom of time, and that idea is really in line with the way I work with materials in general, I think. For example, in this exhibition I’m opening, I’m using two wooden boards that I found at the Mawlid, and they were used as doormats as an entrance to someone’s home. But I’m repurposing them and hanging them on the wall and reframing them with glass and clips, which is meant to give you a different sensibility about time and space. These objects speak of absence in a way, and a condition where objects remain and human presence only survives as a visual impression. With prints, for example.

SALANE: That’s interesting. So the footprints in these mats are from the people who helped host the Mawlid.

GREISS: Exactly. And in general, I like to work with objects that have gone through layers of time and usage. I’m also really interested in the way that cities are laid out, and how urban planning affects us physically and psychologically. For a show I had in 2021, I remapped an experience I had on the train, in which I sat on somebody’s train seat that was still warm, and it inspired the entire show because I realized that this warmth felt from the seat created a sense of tension and separation, but our bodies almost seemed to touch. So energy and transfer and chance are elements that form perception in an urban environment, and I feel like you also do this in your work.

The Longest Sleep, 2024, Digital 6K Video, 9.36 min.

SALANE: Yeah. That’s super interesting because I’m very interested in the contact that a city can host. I’m specifically interested in the objects that reflect systems within our place. For example, I think you remember, but at the Whitney, I had this project where the doormats actually remind me of this project a bit. I used coins that I bought from the transportation system at auction, and they were used for bus fare but had no monetary value. And there were tokens from arcades, casinos, and religious places. I thought that this collection accumulated over two years reflected the intimacy of a pocket of a commuter in New York City, and all the places we forget that we have been to. I see that within a lot of your works, that we have this object of contact, but then you don’t have the person present.

GREISS: Totally. Coins are also a peripheral timestamp, just like these doormats. It shows the movement of people, but doesn’t fully define them.

SALANE: And going back to periphery and the Water Lilies and Monet’s lack of horizon, it makes sense. The divisions of foreground and background are just too orderly for how we consume a place subconsciously.

GREISS: Yeah. I feel like you have to crash things into each other to find out what they’re made of.

SALANE: Yes.