Now on View: Housewives Go Highbrow

PRINCESS ALEXANDRA ALBUM, 1866–9

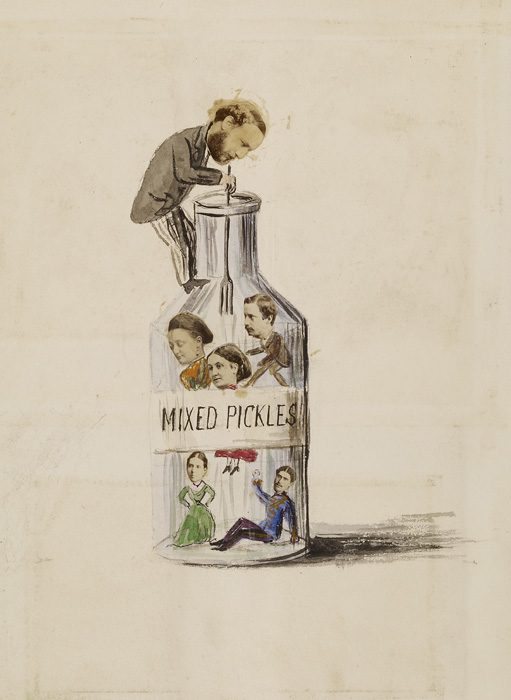

That the transgressive Twentieth Century art of collage was born in the stodgy moors of Victorian high society seems quite counterintuitive. What about the violence of that cut-up, the radically found Dada materials? “Playing with Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage” offers a new look at a the favored pastime of tun-of-the-century aristocratic women, one that would thereafter be associated with artists like Picasso and Braque.

The exhibit features just under 50 works of collaged watercolors and photographs, spanning the 1860s amd 70s. Armed with readily accessible mini-portraits on cartes de visite (business card sized photos that were the craze at the time), the artists spliced faces with anything from household objects to animals with the sort of whimsical and sarcastic surrealism that echoes Tenniel’s imaginary Wonderland.

The exhibit was originally curated by Elizabeth Siegel, Associate Curator of Photography at the Art Institute of Chicago, and here is organized by Malcolm Daniel, curator-in-Charge of the Department of Photographs at the Met.

We quizzed the man in charge to give us a little bit more info on the ladies that stole Picasso’ thunder:

RANDI BERGMAN: Tell us more about the women behind these photocollages. Do you think they meant anything out of these pieces other than to scratch a creative itch?

MALCOLM DANIEL: Definitely more than “scratching a creative itch.” With few exceptions, the works in this show were made by aristocratic British women. In part, the albums were a demonstration of their makers’ talent, intellect, wealth, and social connections. This was the sort of thing—like playing the piano, speaking French, or composing verse—that young women of fine upbringing learned. There are sometimes literary allusions (particularly referencing fairy tales and incorporating pictures of children); sometimes the compositions show a real knowledge of botany or natural history; often the compositions depict scenes and activities that were part of the London “season” (theater, etc) or country house visits, or drawing room scenes, all of which helped place the maker’s family in a certain social stratum.

BERGMAN: It’s interesting to see how the reception of collage would so quickly change into a radical art. What place do you think these women in specific hold in the transformation?

DANIEL: Although these works grow out of the traditions of keepsake albums and scrapbooks, these women are doing something entirely new when they incorporate photographic figures into watercolor scenes, especially those with a fantastic or surreal bent. I don’t think there is necessarily any causal relationship between these photocollages and the work of surrealists and modernists, but it doesn’t keep us from enjoying them because we ourselves make such connections across history.

BERGMAN: What is your favorite piece in the exhibit and why?

DANIEL: It’s hard to make a choice, but I do love the image of human-headed ducks in the Gough Album. The idea of putting human heads on animal bodies seemed irresistible to these women, and even today it’s hard to look at an image like this and not smile. It’s refreshing to walk through an exhibition smiling, even laughing.

PLAYING WITH PICTURES: THE ART OF VICTORIAN PHOTOCOLLAGE IS ON VIEW THROUGH MAY 9. THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART IS LOCAED AT 1000 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK.

ABOVE: WESTMORLAND, MIXED PICKLES, 1864–70. REPRODUCTIONS COURTESY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK