Photographer Kevin Cummins Spent Christmas With The Sex Pistols

“It’s the most important picture I never took,” the photographer Kevin Cummins says of the night that punk was born. He is referring to the Sex Pistols’ first real gig, at Manchester’s Lesser Free Trade Hall in 1976, when the punk genre as we know it was little more than a twinkle in the bloodshot eyes of a few drunk twenty-somethings indifferent to lyrical or instrumental prowess. “10,000 people claim they were there. A lot of the band’s mythology is built around that gig.” The photo in question, had it actually been taken, would’ve revealed the small handful of long-haired seventies youths actually in attendance. In truth, Cummins says, there were no more than fifty people in the room.

It’s almost inconceivable that a band with such a brief career—and such poorly attended shows in its early days—could have the catalytic effect on popular music that the Sex Pistols did: from the Pistols sprung punk (The Clash, Siouxie and the Banshees) and post-punk (Bauhaus, The Cure), almost simultaneously. Part of this, according to Cummins, is due to the otherworldly mystique and inaccessibility that once surrounded celebrity culture. “Bands are stripping away any possibility of an iconography developing around them,” says Cummins. “When I was a David Bowie fan, I wanted to believe he lived on a space ship. I would not have wanted to see an Instagram post of his breakfast.”

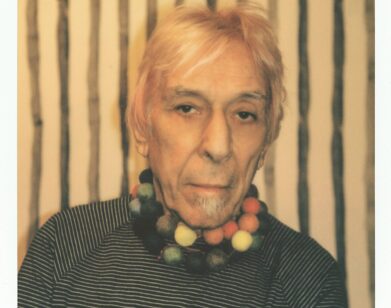

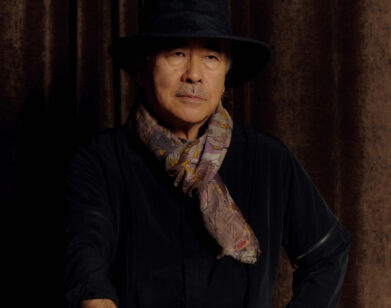

For Cummins, who grew up in working class Manchester just as punk sparked to life, photographing the feral founders of a burgeoning musical movement was uncharted territory. His iconic portraits of Patti Smith, Blondie, The Smiths, and Ian Curtis of Joy Division represent an effort to cultivate a new visual language worthy of a new sound. “We were learning together at that time. I was learning how to photograph musicians and not wanting to do it in an obvious way. They were learning how to pose as a band and not wanting to do it in an obvious way, either.” This feeling—of uncharted territory, heady and unsteady—is palpable in Sex Pistols: The End is Near, Cummins’s recently-released collection of never-before-seen photos of the Sex Pistols’ final gig in their home country.

The Sex Pistols—mangey, gleefully violent and utterly irreverent—managed to simultaneously appall and entrance British society with scabrous lyrics and calamitous publicity stunts. “There was always an element around the Pistols of things being wrong,” Cummins muses of his longtime subjects. It seems that disciples and dissenters alike overlooked the chemically-induced hysteria that colored the band’s every outing, choosing instead to watch their sharp teeth tear through Britain’s social fabric. A drunken rampage through their first record label’s offices, a profanity-laced appearance on the nationally broadcast Today show, and the release of the Pistols’ incendiary single, “God Save The Queen,” (which was delayed when outraged factory workers refused to package the records), raised the hackles of buttoned-up Brits. These episodes, plus countless nightclub brawls, solidified the Pistols’ status as the wayward icons of the punk movement.

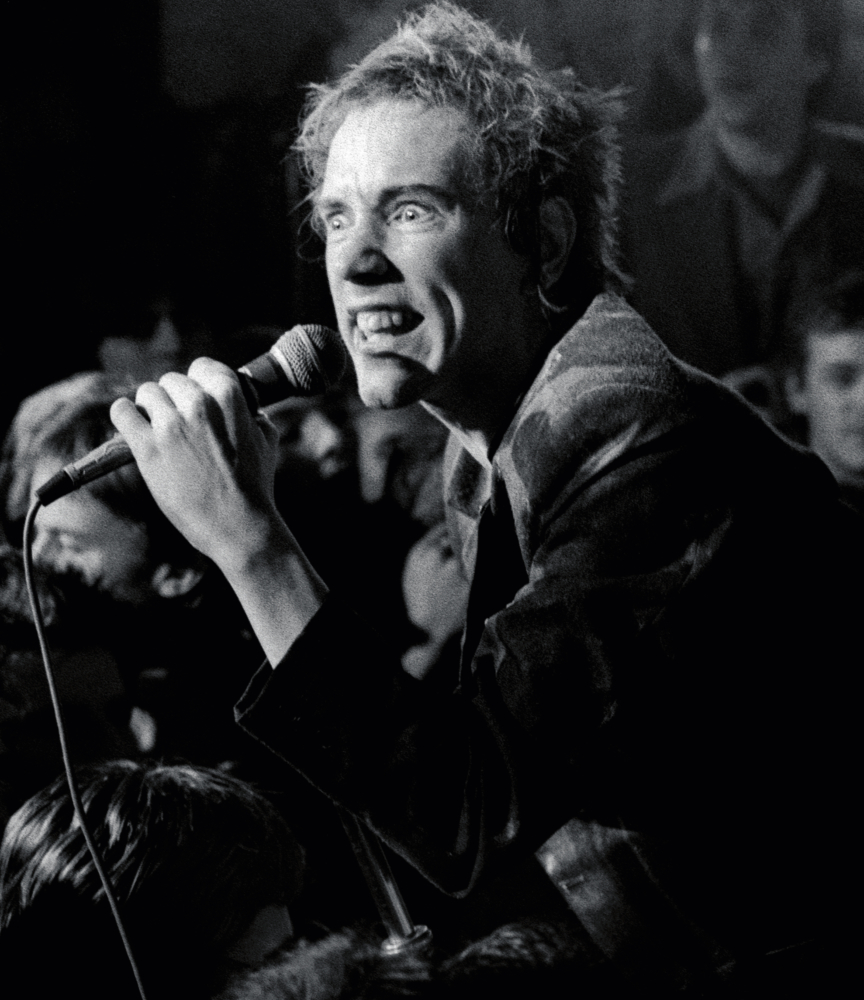

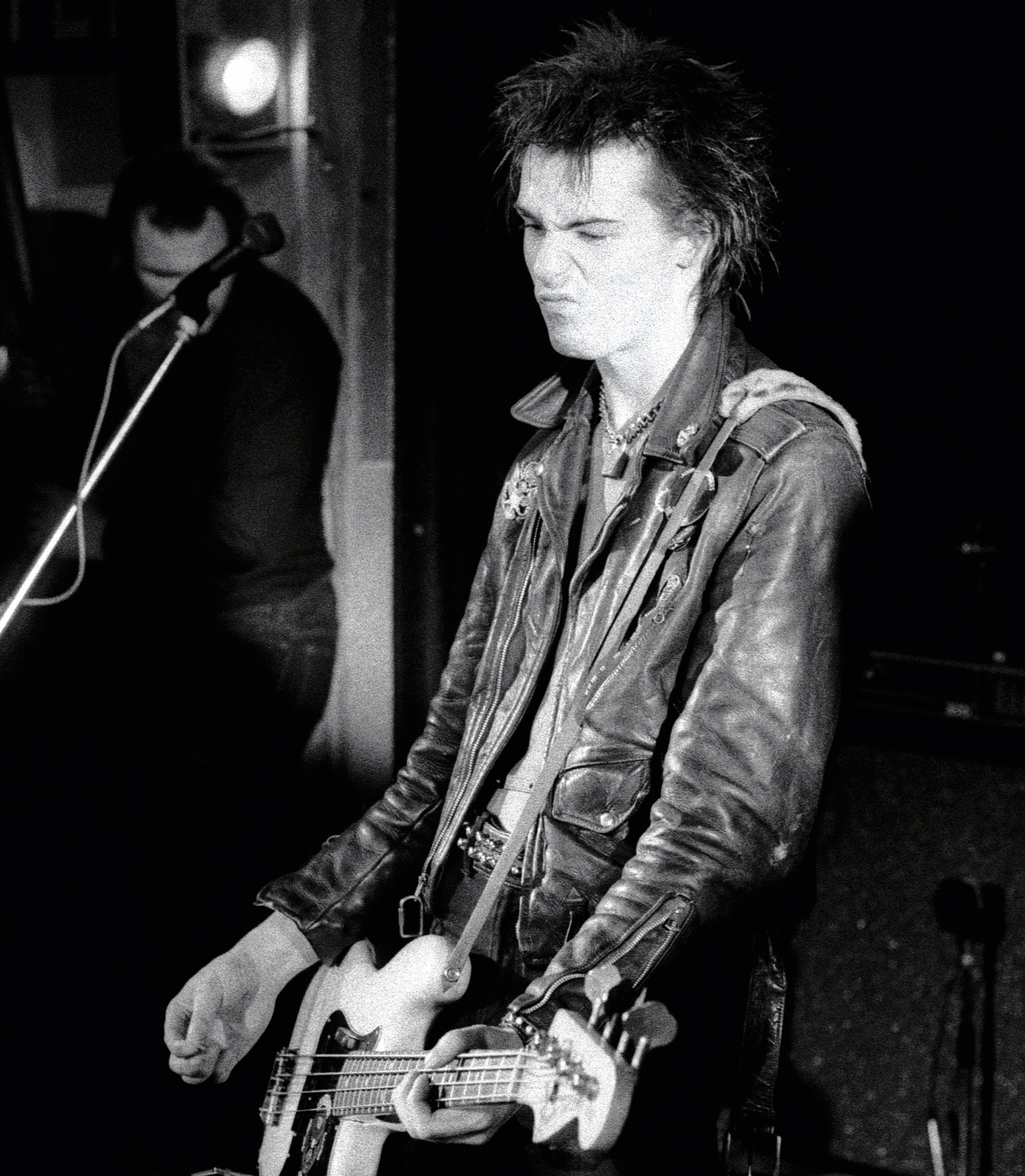

On Christmas Day in 1977, Cummins skipped out on holiday lunch to photograph the Sex Pistols’ naughtiest venture yet. “Even if I wasn’t photographing the most hated band in England,” Cummins laughs, “it was sacrilegious to leave the house on Christmas back then. My father didn’t speak to me for three weeks.” His decision to attend the gig proved momentous. Despite the band’s reputation for violence, the atmosphere at the Christmas Day show—which would turn out to be the band’s last in their home country—had an entirely different feel.“The lads were in great spirits. There was a real joy in the room.” Cummins’ photos, taken from the stage, loom in the faces of a wild-eyed Johnny Rotten and a snarling Sid Vicious. Even as their eerie contortions send a shiver up the spine, it’s clear that they’re enjoying themselves.

Just a year after Cummins snapped his momentous Christmas day photos, “everything just went…wonk.” An ill-fated U.S. tour rigged by the band’s manager bypassed major cities in favor of more volatile backwaters. Exploited by their management, at war with one another, and perilously addicted to heroin, the Pistols limped their way through the pool halls and biker dens of the American South. The tour unravelled as soon as it began; the band dissolved and Sid Vicious retired to the Chelsea Hotel, where he died of a heroin overdose.

Cummins’ photos document the brightest moment of the Pistols’ riotous run, securing their status as a perpetual symbol of the counterculture. This level of cult mystique, he feels, is nearly impossible for a band navigating today’s overshare economy to attain. The fewer the selfies, the more likely it is that your favorite band recuperates on a space ship between tours. From rationing film to the sanctity of the backstage dressing room, Cummins makes the case for the allure of inaccessibility.

———

MARA VEITCH: What were your first impressions of the Sex Pistols?

KEVIN CUMMINS: I went to see them at a concert in Manchester in June ’76 because I’d read a few reviews. I didn’t take my camera, because I’d read that their gigs were quite violent. I couldn’t afford to damage the only camera I had.

VEITCH: You came of age right as the punk scene was beginning to take hold in the U.K. How do you document a movement when it’s just blossoming? What made you good at it?

CUMMINS: I don’t know really. I did study photography, but I think what makes you good at working with musicians is a totally different thing. It takes a lot of patience. You’ve got to be ready to sit around hotel lobbies for several hours straight. [Laughs] I could do a book of photographs of hotel lobbies.

VEITCH: That would appeal to a very different audience…

CUMMINS: The interior design types, yeah. I think journalists would also be into it, though. They end up loitering in lobbies a lot too.

VEITCH: What do you think that music culture is missing now? What do you miss most about the way it was?

CUMMINS: I think bands give too much information away these days on social media, and it’s a real shame. They’re photographing themselves every second of the day, backstage, coming on stage, even sometimes photographing each other on stage. Whereas back in those days we were working to build some mystique around a band. It used to be that the dressing room was sacrosanct. If we were invited into a dressing room before a gig, it was a big deal.

VEITCH: What is the responsibility of a photographer in contributing to the mystique and iconography of a band?

CUMMINS: In the pre-digital days, if I told you to check out this new band Joy Division, the only way you could hear their stuff was by going to see them live, or on a late-night radio show, or if they had records out. So, I always felt my responsibility as a photographer was to kids like me in working-class neighborhoods or in other parts of the world who might not be able to hear them play. I always felt it was my responsibility to try and explain what a band was like through a photograph.

VEITCH: So, it’s about the rarity of the image?

CUMMINS: Yeah. I think the fact that there are only five frames of that moment with Ian Curtis [the lead singer of Joy Division] wearing the overcoat and holding a cigarette is what makes it such a powerful image. I never used more than two rolls of film for a shoot, because I paid for my own processing. You had to try and make every shot count, there was no room for waste. These photos would emerge as the only evidence that a show had even happened. If we’d had the same technology in the ’70s that we do now, I could’ve taken a hundred shots of Ian, but they wouldn’t mean anything.

VEITCH: Some of your portraits have become inseparable from the musicians themselves. When you look back at them, do you ever wish you’d composed them differently?

CUMMINS: I definitely would’ve gone about some of them in a different way. I suppose it’s the fact that we were learning together at that time. I was learning how to photograph musicians and not wanting to do it in an obvious way. Then they were learning how to pose as a band and not wanting to do it in an obvious way either.

VEITCH: You were trying to create an entirely new post-punk aesthetic and attitude.

CUMMINS: There was the sense of that, definitely. Particularly with the Sex Pistols’ Christmas gig.

VEITCH: Besides the obvious importance of the occasion, is there anything else about this collection of photos that’s special to you?

CUMMINS: I shot them from the stage, which gives you a real sense of the energy in the room. You see the audience, and you can feel what it must be like to be on stage and be adored for an hour.

VEITCH: Was it a pretty typical Sex Pistols show?

CUMMINS: No, it was very different. A normal pistols gig always had an element of aggression or violence, but this one didn’t at all. I think we all felt we were part of a VIP club who’d gone to a gig on Christmas day, like some secret society.

VEITCH: Obviously, the demise of the band during their U.S. tour had a lot to do with addiction. Was this show part of a purer time for them, before that spiral began?

CUMMINS: In some sense, I think so. They did take a lot of speed back then, and Sid [Vicious] was taking heroin. Nancy Spungen [the infamous girlfriend of Sid Vicious] was at the gig, but this was before everything went sideways. They were just a bunch of lads, they wanted to go out and play gigs. But Malcom wanted to create this buzz around them, and turned the public against them.

VEITCH: What were some of the big moments for you as you got close to some of these bands during a time when a lot of people were struggling with drugs?

CUMMINS: Ian Curtis’s suicide was the first one, really. It was clear all along that Ian wasn’t well. He was actually having seizures onstage. They called it his “epilepsy dance.” We didn’t really understand what epilepsy was. It was seen as a mental illness, which wasn’t really talked about. He was struggling with his personal life too. He got married in the way a lot of working-class lads in England get married—far too young, just so they can leave the family home.

VEITCH: Were there any special moments with any of these artists that stuck with you?

CUMMINS: Most notorious bands never carry money. Morrissey once offered to buy me a drink once in a bar in Tokyo, and I was quite surprised.

VEITCH: Did he pay?

CUMMINS: Well, he put it on my room in the end. At least he ordered it.