KINK

Photographer Florian Hetz Wants to Abolish Artist Statements

I have a tattoo on my arm that says “Property of Florian Hetz,” and I’m not joking. Hetz and I had both been artists-in-residence at the Tom of Finland Foundation in Los Angeles, and though our residencies didn’t overlap, Hetz came to one of my band’s concerts in L.A. and we got to shoot the shit and become homies. I ended up in one of his photo shoots in a hotel downtown, and I remember sitting at the end of his shutter feeling like a form of hallmark. I knew his work, but like, who was he? As far as personal mythology goes, he suffered a form of brain trauma in the past—don’t fret, he’s safe now—though at the time it would randomly cause lapses in his short-term memory. So he began photo-documentary as a form of visual timeline to keep the blur between past and recent present manageable.

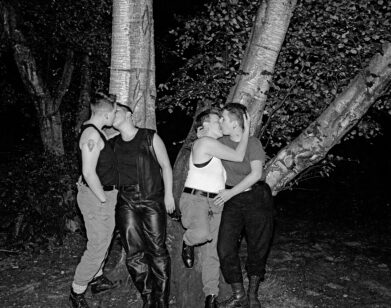

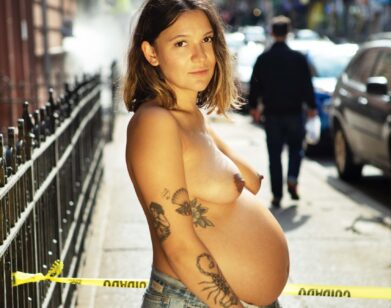

He does boast more traditional work that lends itself to portraiture, or what I like to call “ho pics.” Speaking of ho’s, there are a lot of them on the internet these days. And as we watch beautiful, fit, muscular bodies blend into one note, there is something that deeply enamors me about Hetz’s work. They’re his “anonymous” photos, the ones that lack a face conveying or emoting. With portraiture, that’s what we rely on to understand how to “feel” about a subject, but oftentimes his photos don’t attach a face or even an entire body. In close up, you understand them more: a tip of a clenched elbow turned sides, or an Adam’s apple being gripped tight from behind with a hand, or beads of sweat accumulating on the small of someone’s back. Objectification, simply stated, is the depersonalization of a subject. Hetz’s work is an elevated form of objectification, based in an abstractionist lens. More often than not, the effect is poetic. An elbow wrapped in another looks for foreign until I realize what I’m looking at.

Lately, Hetz is wrapped in a community internet battle around his images and whether or not they constitute obscenity. But, true to form, he’s now selling the images to pay the court fees, like a true Renaissance man with the IQ of a goddamn criminal. I always have to change my panties after interviewing him.

———

BRONTEZ PRUNELL: The term “German Fetish Photographer” sounds so cracker and serious and honestly doesn’t describe what a fucking teddy bear you are. Do you describe your work, or even yourself?

FLORIAN HETZ: Fetishes are a funny thing: I have zero attachment to them, nor do they really have space in my work. But I see how people can write their fetishes into my photos. For me personally, the origin stories of an individual fetish are interesting. I want to know how someone found out that banana peels turn them on. But for my work, it’s not important. Sexuality happens sometimes in my photography, but it’s by far not the most important part. I always had a very relaxed view on sexuality and all of its facets and I treat it the same way I treat other things: with lots of curiosity. My photography is pretty clear and therefore I don’t want a buzz word bingo text to describe them. My work is not “researching and dissecting the fragmented intimacy of non-binary queer safe spaces in times of toxic masculinity and trauma in the global south…” It’s time to give the viewer a bit of credit and trust that they can come to their own conclusions. Let’s abolish artist statements. I like myself the most when I’m in places where I don’t know anyone. Everything has so much potential then, myself included.

PURNELL: You were the bar manager at Berghain in Berlin for 11 years, right? What effect do you think that had on your art, if any?

HETZ: The effect was probably the opposite of what most would expect. Constantly dealing with individuals on the verge of every possible breakdown made me want the opposite in my life and in my work. In the last 15 years, Berlin has turned into this kind of weird sex and drug resort. We created a nightlife industry, a Disneyland for grownups that lives from international parties and sex tourists. Nightlife in Berlin comes with a pre-packaged aesthetic: the black transparent polyester clothes, the pseudo-coolness and blasé facial expression, darkroom pale skin with the mandatory tattoos, after-hours in dirty apartments in Neukölln, captured in unfocused snap shots made by analog cameras. None of that happens in my photography. The club and Berlin dont play a role in my work. But working there did give me access to people who were interested in sitting for my photos.

PURNELL: I feel like your work sets out to answer and also problematize questions about sex, desire, bodies, how we are reading these things. Do you have any set agenda, or is it kind of improvisation?

HETZ: My work deals with what I see, but probably in a more non-documentary way. I never wanted to be a photographer, but my encephalitis caused a big memory loss. After I left the hospital, I started to take photos in order not to forget stuff. I took them for me and only for me. And they worked like crotch. But they were snap shots. When I started to properly take photos, I went into a shoot overly prepared, sketchbook and all. I had a clear idea what I wanted to shoot, the end result was already in my head. And that way I learned how to use a camera and to understand lighting. But that also restricted me after a while. There was not much space for anything else. So when I started to go to L.A. I switched up a few things from my routine. And one of them was that I went into shoots without any preparation. This way I learned to enjoy errors and concentrate on what was in front of me. Photography for me is about seeing, and noticing things that others might not pay attention to.

PURNELL: Besides the money, do you take any pleasure in doing commercial work?

HETZ: If I get a carte blanche, I enjoy it immensely. But if not, I’m the wrong person for the job. I admire artists who can cater to a client’s needs. When I do commercial work, I don’t let anyone on set who is not in front of the camera. I understand that this can make clients and art directors nervous. But in the end I need to feel comfortable and I won’t if there’s someone constantly trying to inject themselves into my work. That probably makes me complicated in the eyes of many, but I can live well with that.

PURNELL: Are you classically trained as a photographer? Can you process photos in a dark room by yourself?

HETZ: I learned in school how to develop and process black and white film, but I didn’t take photos then. I only started to enjoy taking photos when digital cameras became more accessible. I really like developing and color correcting a raw file. The whole post-prod aspect is fascinating. It’s like a meditation to sit alone in front of the computer and develop a file. I probably would have also enjoyed just the same working in a darkroom. And if I would have learned how to develop color film, I might have started to take photos earlier. But I find the idea scary, to rely on others to do things like that for me. From the moment of taking the photo until printing it, I don’t let anyone else handle my photos. Do I have control issues? Duh!

PURNELL: Did you go to Art School?

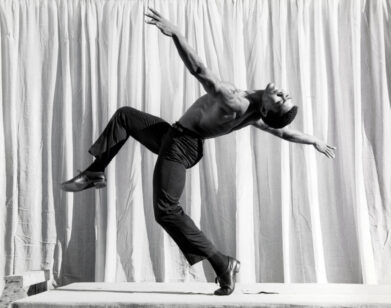

HETZ: I didn’t. After I finished school I was busy running Germany’s first professional piercing studio. Then designing costumes for opera and ballet got in the way. Eventually I studied arts management, got a brain injury, worked in nightlife and then somehow started to take photos. But from 12 years on I collected photos and art books and magazines, mostly stolen. And like many faggy kids, I watched every old Hollywood movie there was and read day and night.

PURNELL: You split a lot of your time between your native Germany and Los Angeles. Do you ever dream about being a full time Angelino?

HETZ: Every single time I arrive at LAX, they put me in that little interrogation room for a couple of hours and I have to explain to them that I really like being in L.A. as a visitor for a couple of months but that I enjoy living in Europe. Los Angeles is a wonderful place for me to escape the winters here. I don’t drive, but I have a bike in L.A. and that’s how I explore the city, on my bike with a camera in my backpack. Every time I come back to Los Angeles, I am blown away by the quality of the light. It’s so understandable that the film industry settled there. L.A. without sunshine is a different story, though. I’ve been there from February to April in 2023 and it basically continuously rained. And all of a sudden, a lot of things didn’t make sense anymore. The photos from that time are pretty dark. Right now I’m working on a book about my time in L.A. from 2017 to 2023. It’s interesting to see how my view on the city has changed over the years.

PURNELL: Should I get my “Property of Florian Hetz” tattoo covered? I think people are getting the wrong idea.

HETZ: Hell no!

PURNELL: How is your censorship case going? If you feel like talking about it…

HETZ: Nothing has been decided yet, but the bottom line is, there’s a politician in a part of Germany who’s going on a personal crusade about internet pornography. He is either using A.I. or poor interns to go through twitter accounts to find posts that include sexuality and then he makes an offense report to the police. They have to hand it over to a judge and, if things go wrong, you’ll get convicted for making pornography available to minors. So it’s not about, “What is pornography?” but about making it available, which raises a lot of other questions. Like, does he understand how the internet works? If things go south, l’ll have to pay €3000 to €4000. Right now, I’m thinking about creating a limited edition box with fine art prints of the four photos that they objected to, to raise funds.

PURNELL: Beyond sex and desire, what are the biggest questions you are trying to answer with your photo work or your life in general?

HETZ: I am not trying to answer questions for others with my photos, neither should this be my job. My photos are highly subjective commentaries of things I notice and surround me. They reflect who I am in this moment, and where I live, and they are the result of how I look at things, literally and figuratively. Do they answer questions for me? No. But they are the end of a long process that started 20 years ago already. Somehow, they serve as my personal vanitas.