butts

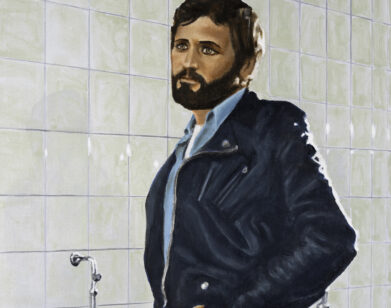

Photographer Chivas Clem Takes Jack Pierson Inside His Archive of Drifters

Greg with My Grandfather’s Shotgun, From Behind, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

This week, Dallas Contemporary opened Shirttail Kin, a hard left turn from their regular programming. The transgressive exhibition includes 70 portraits by Chivas Clem documenting a nomadic community of drifters—generally white and socioeconomically impoverished—he encountered upon returning to his hometown of Paris, Texas. “Most of them are felons and don’t vote and have no relationship to politics,” Clem said of the men featured in his uncompromising images. “They live in a class outside of the lower class.” While they might have seemed like an odd choice of subject for Chivas, a queer, 52-year-old artist whose shown his work in New York and Los Angeles, Dallas Contemporary found the photographs—stark and vulnerable documentations of grit, aimlessness and freedom—particularly fit for exhibition about of the November election. Just before he headed down to Dallas to pin the portraits on the museum’s wall (but not in a Wolfgang Tillmans-y way, as he clarified), Clem jumped on a call with fellow photographer and friend Jack Pierson to talk about the thorny matter of exploitation and the process of immersing himself in a world of “theft and grift.”—EMILY SANDSTROM

———

JACK PIERSON: How are you?

CHIVAS CLEM: I’m okay. I’m kind of nervous about the show, but obviously very excited.

PIERSON: Right.

CLEM: I’m going to Dallas after tomorrow to start installing.

PIERSON: Oh, my goodness. That’s exciting. How did you finally resolve getting them on the wall?

CLEM: We just decided to pin them.

PIERSON: Oh, goodie.

CLEM: Which I think will be fine. I feel like it’s sort of coded as being Wolfgang Tillmans-y. But I don’t think it has to be. I can figure out a way to not do that. Lots of people were doing it before he was.

PIERSON: Oh, really? Name one.

Drifter on my bed, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

CLEM: Oh, I don’t know. [Robert] Mapplethorpe, or you, obviously. Is that the answer you were looking for?

PIERSON: Mappethorpe never pinned anything. His frames were the best thing about the work.

CLEM: I know. Anyway, I’m excited about it. It’ll be interesting to see how it’s received in Texas, which has a more conservative audience than say, New York or L.A., where I feel like people were really into it.

PIERSON: So, what ever possessed the institution to do this show? It seems like quite an outrageous choice for them. I mean, even you must agree?

CLEM: No, absolutely. It did seem outrageous. I think Alison [Gingeras] is a provocateur, and she thought that it would be an interesting choice with the election coming up. I had talked to her about how in the beginning of this project, I was creating an archive of images of rednecks and deplorables, and I was trying to think about what a deplorable looked like and what white male rage looked like.

PIERSON: Did you get away with saying that? Deplorables? Didn’t even Hilary Clinton get in trouble?

CLEM: Well, I’m quoting. It’s not my word. Mostly I had spoken about them as rednecks, but really the project was about these lower-class white men who were full of rage, that had trucks and Confederate flags and were characterized by their racism, their transphobia, et cetera.

PIERSON: Is that the basic profile of most of your models? They all seem somehow so sensitive to me. Or is that your skill as a photographer?

CLEM: I think that’s my skill as a photographer.

Cole with dead hawk, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

PIERSON: I had the impression that a lot of them were friends of yours, or that you made friends with them. Are they actual Trump supporters?

CLEM: Well, yeah. But I would imagine they’re totally disengaged from politics.

PIERSON: That’s what I was going to say. Do they even have an opinion?

CLEM: No-

PIERSON: They don’t have trucks. They don’t have Confederate flags. They don’t have anything. No?

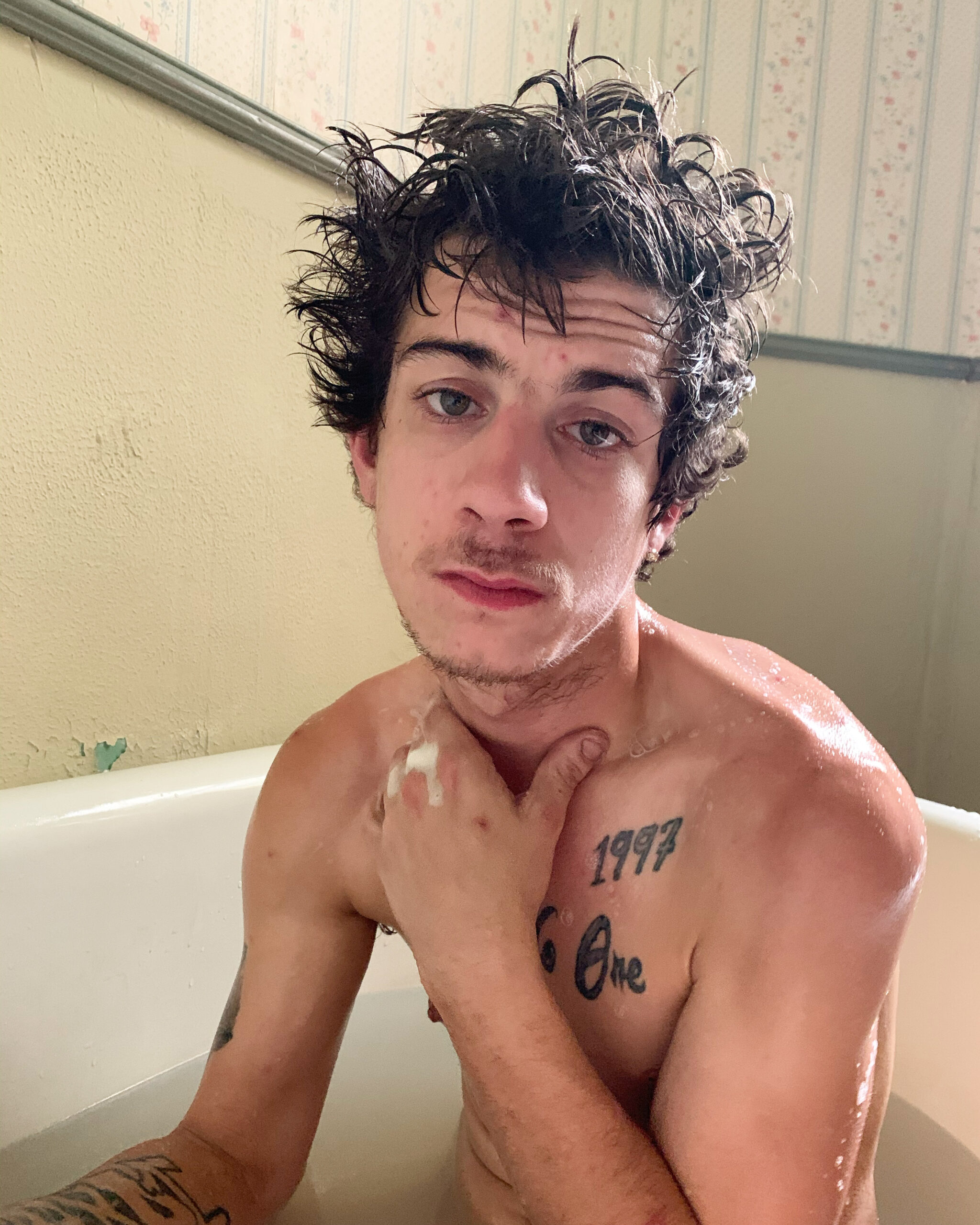

CLEM: They don’t have anything. But they’re born of that culture, right? Most of them are felons and don’t vote and have no relationship to politics. They live in a class outside of the lower class. They’re drifters. Some of them are sort of hobo-like. When I come back, I am surrounded by that. I knew some from my neighborhood, and they would come to the studio, and they were terrible helping me out. So, I’d be like, “Why don’t you just lay around and take off your clothes and smoke and let me take your picture?” That’s how I started. I asked them to hang around the house, and they would take a bath or they’d take a nap or they’d eat a banana and I’d take a picture.

PIERSON: Perhaps we should say the name of your town.

CLEM: Paris, Texas.

PIERSON: Fantastic. So loaded.

Coty in Abandoned House, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

CLEM: Yeah.

PIERSON: I’m completely simpatico with what you’re doing. But imagine yourself in front of the graduate department of photography at Yale, Columbia, any high-class art school. How are you going to defend it to a Gen Z kid or, worse, a millennial, who sees what you’re doing as exploitative? I know from teaching the kids a lot of these days that they don’t feel like they have a right to photograph outside their own cultural background.

CLEM: Yeah.

PIERSON: So how are you anything but a privileged person preying on the financial needs of drifters and hobos?

CLEM: Well, I decided that if I approached the work with integrity and a real, authentic desire to capture them, I didn’t feel like I was overstepping any moral boundaries. I never felt like I was exploiting them. They enjoyed being seen, and that was almost part of the work. It’s like I was working in concert with them.

PIERSON: I see that fully in the imagery.

CLEM: I think that unnecessarily hurts artists when it puts you into a box like that, where if somebody comes from a middle-class background, then somehow they’re not supposed to engage with people that are socioeconomically more impoverished or something. I don’t think you can get anywhere with that, and I couldn’t have made this work in those kinds of environments. Maybe because I was outside of the academy, outside of the art world, that’s what allowed me to do this.

PIERSON: Right, if you lived in New York City–

CLEM: Exactly. When I was a kid, these were the people that I was terrified of, that tortured me and there was something about reaching out to them. I felt like they’re outsiders now in a way that I’m an outsider. I didn’t feel above them, I felt a kinship with them. That’s why the show is called Shirttail Kin. I developed this enormous fondness and tenderness for all of these guys, despite us coming from very different backgrounds, but also being white men in the south. There’s an honesty to the work that supersedes that kind of thing.

Cole in Blossom, night, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

PIERSON: I’d agree with you, but it’s a question worth asking, because I’ve heard it time and time again.

CLEM: Sure.

PIERSON: I think it’s ridiculous, but I’m also an old white guy.

CLEM: I think I’ll get plenty of blow-back about that. It’s a legitimate question. In some ways, I started the project very naively, and that never really occurred to me until recently when I started showing the work to people and doing studio visits. People slowly started asking those kinds of questions.

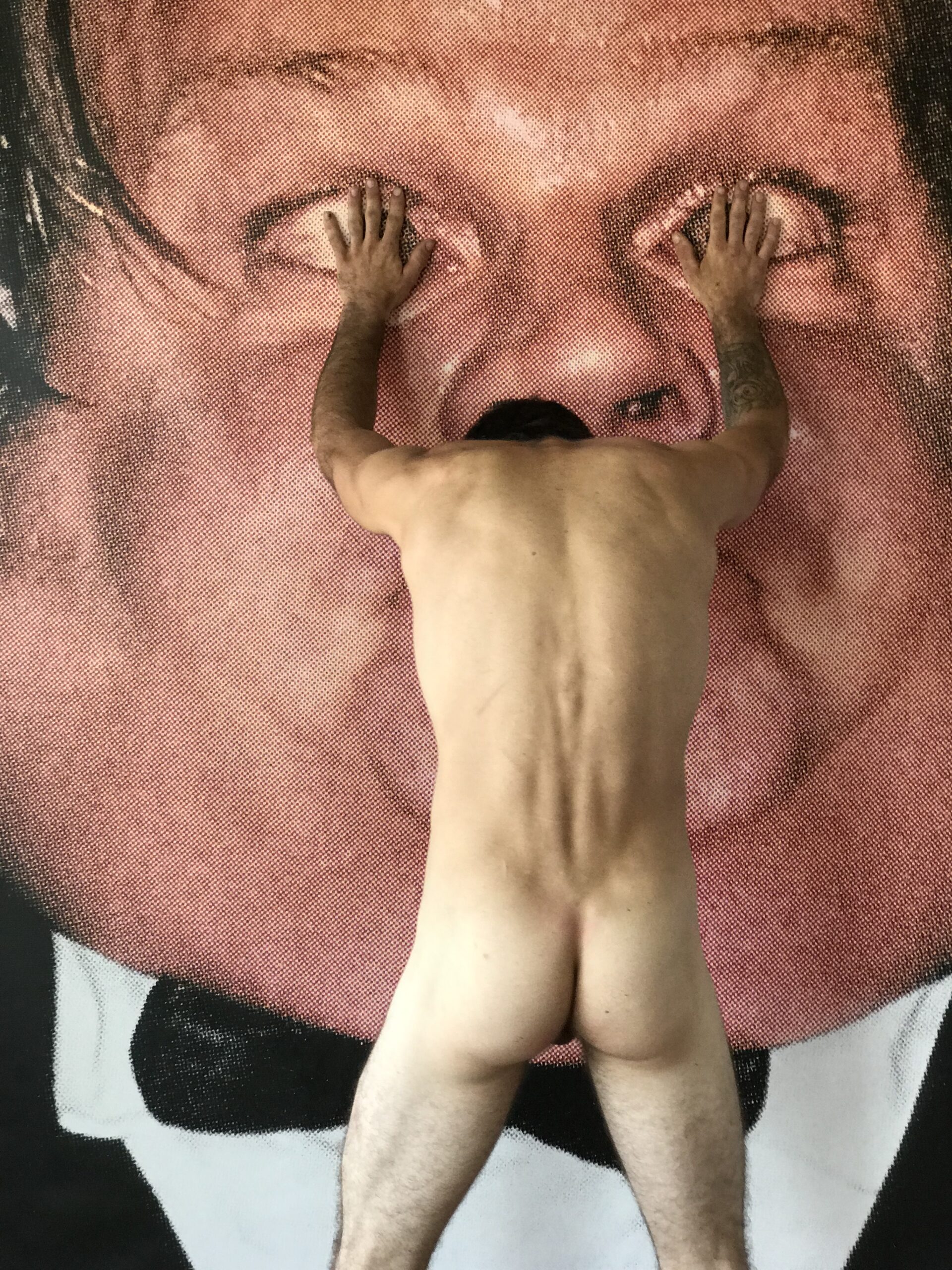

PIERSON: Well, the other funny thing is, if you were an actual pornographer with a Las Vegas studio and you were paying white guys to perform, I don’t think that question would come up. It’s just like, “Well, it’s porno.” It comes up now because you are positioning it in a museum or a public institution.

Cole in front of Chris Farley, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

CLEM: It’s true. I don’t know what happened in the art world in the past, say, 15 years, but art more and more is reflected in our pop culture as this kind of propaganda for white neoliberal utopians. Does that make sense?

PIERSON: Yeah.

CLEM: An interviewer asked me the other day, “Aside from hope and compassion, what did you bring to your models?” And I’m like, “I didn’t bring hope…”

PIERSON: $50.

CLEM: Exactly. I paid them for working for me. Of course, I ended up becoming very close to them, but I didn’t rescue them from poverty or something. People want to see the work as me sort of reaching out, but that’s not what it’s about. Did you ever see that interview with [Pier Paolo] Pasolini? He’s talking about—I can’t remember the Italian term for it—but it’s similar to peasant. It’s somebody who has not been touched by bourgeois values like materialism. He said that he always felt very close to young people who were naive to bourgeoisie values. That’s something about my models, too. Despite the fact that they’ve had rough lives, there’s a certain freedom in that.

PIERSON: Yeah. I think the only other place you get that essence is from the super rich.

CLEM: Yes.

Dillon at the carwash, Night, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

PIERSON: I’ve always maintained that the super rich are exactly the same as the super poor.

CLEM: That’s exactly what he talks about in the interview, and that what he most despises is the middle. And because these guys have never been touched by the middle, there’s this beautiful naiveté and this real poignant innocence to them, which I hope to have captured.

PIERSON: I’m also thinking of David Hurles, whose work you must know. He was a ’70s pornographer from central Los Angeles who was focused on a certain kind of very rough individual. He just considered robbery and violence part of the game.

CLEM: It’s part of your resume.

PIERSON: Or part of the expenses. You’re going to get stolen from a certain amount and beat up a certain amount.

CLEM: Yeah.

PIERSON: Have you encountered that yet?

CLEM: Absolutely. My boyfriend found a needle in my car, but I just consider that part of it. I’ve only ever had one model who was an actual sociopath and threatened me once, but he came back the next day and apologized. Most of them have been very gentle. But what I learned was that everything is transactional, despite however many tender feelings I had toward them. It kind of hurt my feelings in a lot of ways, but I had to get used to it. Theft and grift are all a part of the project.

Coty in the Bathtub after Breaking In, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

PIERSON: Interesting. I mean, that’s a lot.

CLEM: It has been a lot. When I started doing it, I really didn’t intend to use the photos. I started by filming them, and I made this piece where I had different guys reading Sylvia Plath’s Daddy. So, all the pictures were studies, and then I was putting them on Instagram, and Peter McGough called me out of the blue one day and said, “These are great. You should show these.” He’s like, “You’d be crazy not to show these.” And I was like, “I don’t know. I’m not really a photographer, per se.” And he was like, “That doesn’t matter. They’re great. You should show them.”

PIERSON: That’s fantastic.

CLEM: Jessica Craig-Martin was another person that was like, “You should do something with them.”

PIERSON: Your first show was at Bortolami?

CLEM: With this work?

PIERSON: Yeah.

CLEM: Yes. I was in a group show in L.A. at Tony Payne, and then I did a show with Bill Arning.

PIERSON: Which was in Houston.

CLEM: Yes, before he had his space upstate.

Turnpike to Antlers, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

PIERSON: And since then, have there been any shows of this work?

CLEM: No, there haven’t.

PIERSON: So, that’s a couple years ago now, right?

CLEM: Yeah, it was a couple of years ago. People really like the work, but male nudes are hard sell.

PIERSON: As I well know.

CLEM: As you well know. When I went to L.A., I did studio visits with some very good galleries, some really smart people, and they were all like, “We love this, but there’s no way we can sell it.” And I think at this particular moment, galleries really need to sell things. Galleries can’t afford to show things that don’t move. So, I don’t have a gallery. I have a small gallery in Dallas, but she doesn’t even really like the work and–

PIERSON: [Laughs]

CLEM: No, I’m serious.

PIERSON: I believe you.

CLEM: Occasionally, I’ll sell something here or there to somebody, but I don’t have a gallery.

PIERSON: You might have to explore alternative spaces.

Jer eating catfish with dirty fingers, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

CLEM: Yes.

PIERSON: Like places where Bruce LaBruce or Genesis P-Orridge would show. In every city there’s some pocket of renegade.

CLEM: It’s true.

PIERSON: I do think the work should be known in a broader way.

CLEM: I mean, I’d like to show it and sell it and maybe it can enter the marketplace at some point. I mean, years ago, they said Mapplethorpe would never ever be able to sell. Of course, he made all of those orchids and things that sold really well, but I guess they didn’t show those in the beginning, did they?

PIERSON: I think they showed them, but with plenty of the other stuff that could sell.

CLEM: Yeah.

PIERSON: You’ve got pretty trees behind you. Every once in a while you throw in a landscape or something.

Chris Smoking Outside, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

CLEM: Yeah. There’s other things, there’s landscapes and sometimes a flower. But they mostly wanted the portraits and the nudes, so that’s what the show mostly consists of.

PIERSON: That’s cool. Well, you’ve got a great golden opportunity here to show the work without having to have it be commercial.

CLEM: Yeah, and there’s a catalog, which is incredible. Hilton Als wrote the essay.

PIERSON: That is incredible.

CLEM: I mean, who could ask for more? It’s like the best thing that ever happened, really. And now I’m going to be in Interview Magazine. It’s like, I’ve arrived.

PIERSON: Well, congratulations.

CLEM: And I’m only 78! Thank you.

PIERSON: You’re not. How old are you?

CLEM: I’m 52.

PIERSON: One year for every state in the union. Well, I wish you the best.