Petra Collins Can’t Stop Using the Snapchat Baby Filter

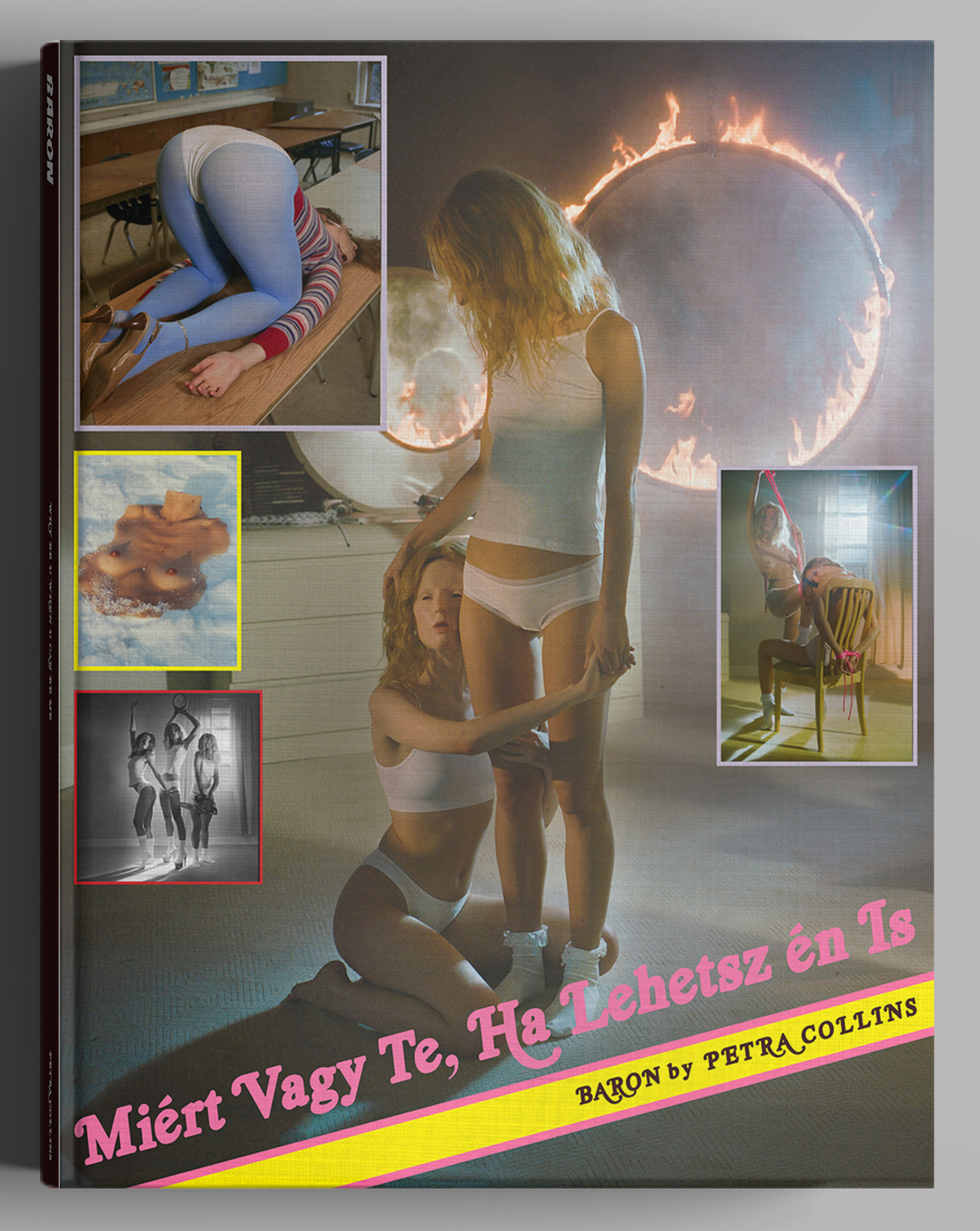

The work of Petra Collins might, at first glance, seem like an aberrant transmission from a dazzling, alternate universe, but to her, it’s just reality. The photographer and director, known for her dreamlike portraits (of the likes of Kiko Mizuhara and Young Thug) and beguiling videos (for pop superstars Cardi B and Selena Gomez) has turned the lens around for her latest book. Miért vagy te, ha lehetsz én is? (that’s Hungarian for “why be you, when you can be me?”) showcases Collins diving into self-portraiture, with some help from sculptor Sarah Sitkin. Sitkin, who is known for silicone molds of the human body that have taken the form of Billie Eilish and Fecal Matter’s skin heels, has fashioned masks for Collins, putting the “self” in self-portrait—but what is “the self” these days, anyway? Interview chatted with the photographer about skin suits, Jordan Peele, and the blurred reality of the Internet age.

———

MARK BURGER: Your new book has some bizarre, unsettling imagery. Are there any specific horror-film influences that came to mind when you were making it?

PETRA COLLINS: Horror, for me, has always been my favorite genre. I’ve dabbled in it a couple times before. It’s funny–I look at the photos, and I think they’re so beautiful, but I forget that I’m very desensitized to them. I have some friends that are like, “Okay, I love you, but these are really gross.” I’ve been shooting other people for, like, fifteen years now, and I had been constantly doing work on myself, but I hadn’t necessarily gone so deep as to fully explore myself in front of the camera. Sometimes when we create work around, or even do medical things based on the body, we forget that it’s connected to a soul or a person. It’s one thing to do self-portraiture–setting up the camera and taking it and being in front of it–but there’s something to say for actually being able to be behind it, holding the camera, and shooting yourself. It’s a replica of the body, but it’s still so powerful and strange. It takes it to a weird other level. Any fears you have towards yourself, whether they’re violent or dysmorphic, they come out.

BURGER: The title of the book is in Hungarian–what was the inspiration behind it?

COLLINS: It’s in Hungarian because I am Hungarian, and it was my first language. I think it’s interesting when you’re a child who grows up without English as a first language. You have to learn it, and then you have two languages, and you feel like your self is separated. In the early 2000s, there was this public service announcement in Canada that had that tagline: “Why be you, when you can be me?” It’s these two girls who go into this shop that has all these machines they can step in, and then it turns them into this other person who’s perfect. It always freaked me out. It’s scary, but it’s also something I might have wanted. Today, people can literally change their faces and look like totally different people, and that’s normal and accepted. You know that Matt Damon movie, Behind The Candelabra? Liberace had that partner who got plastic surgery to look exactly like him. It’s bizarre, but it’s something that we don’t discuss at all because everyone is changing their faces and it’s normal.

BURGER: With the advent of FaceTune and the Snapchat face filters.

COLLINS: There are so many times when I open my phone camera and flip to a filter just to see myself through it. I think the most bizarre one is the baby filter on Snapchat. When I started taking photos, selfie culture was just starting, and we didn’t have that many things to morph or change about ourselves. It’s almost like the internet has leaked into real life, and real life has leaked into the internet. They’re not separate—it’s this one, confusing mess. I’m like, “Wait, I don’t have this dog filter on me all the time?”

BURGER: The photos from this new series aren’t quite body modification or body distortion, but somewhere adjacent to it. It has the elements of your past editorial work, with those glossy, saturated tones, but with images that are jarring. Is that something you were intentionally playing with?

COLLINS: A lot of people have asked me why I’ve moved into surreal photos, and for a while I was like, “What do you mean, surreal? These are just normal.” The way I approached this project specifically was to document it as if it was real, because to me, it is. The book has a lot to do with childhood sexual fantasies, and places that I’d been to–half of it was shot in Toronto, and the other half was shot in studios. On one set, we built a replica of my childhood bedroom. I think a lot of what we perceive as reality has shifted. I’ve gone back to reading Simulacra and Simulation, which is something I read in school and I had never been able to apply it to real life. Now, someone can create an existence online that slowly bleeds into their real life. I think we have to re-think reality. Something that I’ve seen so much in advertising, maybe in the last year or two, is this shift toward the surreal. When someone says, “We’re gonna capture the real thing,” everyone knows that isn’t what’s necessarily going on.

BURGER: So maybe the book isn’t a juxtaposition, but a merging of multiple realities.

COLLINS: For me, it’s more of a mirror.

BURGER: If the baby filter is your favorite one, what should the next big Snapchat filter be?

COLLINS: I’ve started to get obsessed with this Korean app called Snow, which has really good filters. I’m trying to pull myself away from it. I’m too obsessed with the baby filter. I had to delete Snapchat and Instagram for periods of time. I realized I’ve missed out on a lot of IRL things. It’s crazy because now it’s such a luxury to leave your phone in the car when you get out. I don’t need any more filters. The baby filter was maybe my highest point and my rock bottom.

BURGER: Do you have a favorite horror movie?

COLLINS: I loved Us. I think the reason horror is coming back is because it’s the best genre to subvert, but it’s also the realest that we can get. My coming-of-age movies were Carrie and The Exorcist. That’s where you go to see a real mirror of the world. It’s so exciting to see what Jordan Peele develops into, or what he can do with a bigger cast and a bigger budget. I hadn’t gone to a movie in a while that took me on such a ride–where I cried, I laughed, I was holding breath half of the time. That is where the conversation should be, and that’s where we’re missing it. In politics, or in any sphere, we’re so hyper-focused on things that are super niche. I think it’s important to be able to speak to a wide audience, and whatever little bit of justice you get out of it is a triumph.

BURGER: Do you have any irrational or orthodox fears? Like, every time I lean against the subway door and it rattles, I think, “This is the time that it’s going fly open and it’s going to be some freak, tragic accident.” It’s completely in my head, but you can’t tell me otherwise.

COLLINS: I’m literally always questioning reality. I think that’s why I deal with it so much. If I go into a wormhole about it, it’s too crazy. I think doing metaphysics in school was probably the worst thing for my brain. Like, I kind of wish I didn’t know any of this. I think that’s my biggest fear, where I don’t know if what I’m seeing is what everyone else is seeing.

BURGER: If you could bestow upon yourself a genre, would you, and what would it be called?

COLLINS: I probably wouldn’t. I have a fear of being boxed into anything. It’s always been stark reality that I’m shooting. If I could label myself, it would probably be that.