MEN

Peter Vack on Jesus, Male Rage, and Why He’s Not Really a Party Boy

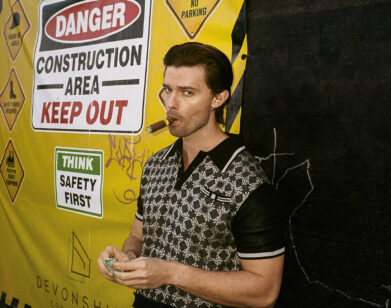

It’s the summer of 2024 and it feels like anything can happen. The East Coast is suffering through a record-breaking heat wave, popular musicians are fighting and making up, hurricanes can be male, both women and felons can be presidents, children can be assassins, young novelists are getting their day in the sun, and tech billionaires are getting theirs on Mars. Everyone’s looking up at the sky, in protective eyewear, towards a solar eclipse and an uncertain future. Think Woodstock ‘69 except swap acid for ketamine, Vietnam for Palestine, and weird group sex for, well, actually not much has changed on that front. Whether it’s a rebirth or a death rattle remains to be seen, but amidst it all enters Peter Vack, young, dumb, and The Master of Cum. Vack is an actor-turned-writer with credits including Mozart in the Jungle, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, Cold Case and his own feature, Assholes. He’s just come out with the book je jour, Sillyboy, a novel by an actor living in New York about an actor living in New York. It’s also a poignant reflection on contemporary anxieties, self-worth and the relentless pursuit of beauty. For a small press—Cash 4 Gold’s debut title—the book’s release was unprecedented; a launch party covered by Bravo, with a warm reception from the Southwest Review and a cease and desist from the Care Bear lobby.

I interviewed Vack twice for this piece. The first time he shows up unshaven—he’s up for the part of Jesus in a Christian Lifetime movie—in basketball shorts, braided hair, and a garment we once called a wife-beater. He’s been working on his upcoming film www.RachelOrmont.com for “literally” 48 hours straight. At the end of each interview on Inside the Actor’s Studio, James Lipton asks his guests the same 10 questions. This tradition was actually inspired by and based on Bernard Pivot’s French series Apostrophes, and that on a parlor game often played by Proust. So I decided to ask Vack those 10 questions. A mixture of sleep deprivation (on his part) and alcohol (on mine) left the interview lacking, the results not up to Proustian standards, so we redid the conversation a week later. But the first time around, when I asked Vack what he’d like to hear god say at the pearly gates, his answer stood out to me as one worth saving: “Aren’t you glad you achieved all your dreams?” he quipped.

Born Peter Brown, the actor changed his name at age 17 to join the Screen Actors Guild. His sister, Betsey Brown, operates in the same sphere of artists in New York City, as does his mother, a shrink to many a downtown headcase, myself included. When asked why the pivot from actor to writer, he simply tells me that “he loves books,” Phillip Roth’s in particular, whose influence is evident throughout Sillyboy.

Vack’s prose is vulnerable and unflinching, imbued with a keen self-awareness. He blazes over the third rail of political correctness, exploring the nature of modern virtue signaling, white guilt, and performative activism. Love it or hate it—one critic calls it an affront to god—Vack has emerged as a distinctive voice in contemporary literature. Judge away, he says, “It’s an honor to be criticized.”

———

MADELINE CASH: How’s it going? Are you done with Rachel?

PETER VACK: Yes. Finally, completely done. I know you can’t really compare anything to a pregnancy, especially if you’re a guy and you’ve never been through it, but it did feel like the longest labor and the last steps were really painful.

CASH: Were you doing this to yourself in a masochistic way?

VACK: No. You’re not the first person to ask me that. The movie has some elements that actually were more ambitious than we had the budget or personnel for. Even people on set, like my DP and producers, were like, “Do you know what you’re getting yourself into with a few of these creative choices?” Maybe it’s this naïveté where I’m like, “It’s gonna be fine.” And then I will myself into accepting it. We did really bump up against the reality of how hard some of the things were to pull off at the end. Those custom subtitles added another level.

CASH: That’s what you were working on all of last week.

VACK: Yeah. That is something another team would’ve taken at least two months to do, and my friend Nate Wilson and I did it in two weeks.

CASH: Was it like, a quirky aesthetic choice?

VACK: Well, it is and it isn’t a quirky aesthetic choice. On one hand, Betsey’s character is literally hard to understand. She uses this baby-ish voice because she’s been raised in captivity and is sort of stunted. Also, the movie uses language that’s not so easy for people to understand sometimes, certain slang, et cetera. But besides that, the problem with the movie before [the subtitles] was that it was just a little too dark, and the subtitles—

CASH: Add levity.

VACK: It’s the spoonful of sugar.

CASH: You’re looking much better than at our previous interview.

VACK: I couldn’t believe that I was walking into the interview with as little sleep as I had. It really did test my vanity. I was not in society, you know what I mean? I miss that a little. Actually, I’m flirting with a little depression now.

CASH: Postpartum.

VACK: Yeah, exactly. I need to get pregnant again, and who’s the father gonna be? And can I afford another kid?

CASH: Do you have a project lined up?

VACK: Getting these things out into the world feels like it’s taking up too much space right now. Godard said that he used to think the most important part of the process was production, but then he realized it was distribution, and I feel the same for this book [Sillyboy], especially in that I did all this work. And not just so it can languish in obscurity, but so it will reach people. And when it does mostly fall to me, a lot of my psychic energy is going into pushing it out. But it’ll be a great privilege to come up with something else. This project is something that’s been with me for so long, I’m really excited to be working on something that is almost less precious.

CASH: Speaking of a crazed Peter, I want to talk about the party that we threw for you. I was not able to attend. Can you tell me a little bit about it?

VACK: First off, there’s a misperception about me that I’m a party guy. Do you agree or disagree?

CASH: I think that you go to a lot of events that benefit you on a professional level.

VACK: Yeah, it’s genuinely novel for me because I was never even invited to parties until 2021. I was kind of like a loner. I had deep one-on-one relationships, but wasn’t involved in any scene. When it felt illegal to go to parties, suddenly they became appealing because there was this promise of them being subversive. I think now I play into it because being social is a genuine part of my personality.

CASH: When you go to parties, do you feel like you’re putting on a persona?

VACK: I really do love people, but I have to modulate into something that doesn’t feel 100-percent natural to me. It’s a little bit of an act, but it’s not an act that I hate. I like it. I want to rise to the challenge. I once read this about myself—I know it’s funny to admit you read about yourself, but I feel everybody does—that I was a notorious party monster. And I remember sending it to my sister like, “Can you believe they said this about me?” But in a way, I think because I’m an actor and I do love to follow scripts, the fact that it was even said has spurred me to want to be more of that. There’s probably some deeper point to be made, something adjacent to main character syndrome that everyone has.

CASH: I don’t feel like a main character. I feel like a secondary character with a big third season arc.

VACK: Are you just selling yourself short? One of my favorite psychoanalytic points came from Louis Ormont, that it’s more important how people see you than how you see yourself. If you feel like a piece of shit all the time but the world sees you as a winner, that public reality is more important. Sometimes that gets me out of bed in the morning.

CASH: Wow. I like that a lot. So, Bravo comes to the Sillyboy launch.

VACK: That happened accidentally. I think they were misunderstanding it was a book launch and just looking for a place to shoot. But again, I have this naive optimism. I think some people who don’t know me have an opinion of me as a cynical guy. But actually, I see myself as a naive optimist. So when Bravo asked me to shoot at the party, I was like, “They wanna feature me and my book! This is so great!” But really, they were just looking for a location and didn’t care at all about the book or me, and sequestered themselves in one room at Gonzo’s. Like I said, I’m kind of larping as a nightlife guy. I mainly just wanted to have a banging party.

CASH: Mission accomplished.

VACK: Did you see that really mean review yesterday?

CASH: I did. I was going to ask how you feel about criticism in general. Is all publicity good publicity?

VACK: When we spoke last, you were like, “You’re gonna get criticized for this.” It felt theoretical and now it’s real. Earlier in my life this would’ve upset me, and I don’t really understand why, but I feel that my skin is quite thick now. I wish I could come up with a formula for the readers about how to thicken your skin. Now, I’m just honored that somebody would publish that. It feels full of emotion to me.

CASH: It means that your book holds enough cultural relevance to garner a public response.

VACK: I’m sure it will drive sales, and we don’t have a PR team, so every article that comes out is good press. If you’re mean to me, you get like 15 minutes of meme fame, even if it’s just on one of my small-ass accounts for the book. Not to be a bitch back, but I read his book and we’re just writing from completely different aesthetic places.

CASH: I think that if the criticism were from someone that you respected or idolized, it would be harder to swallow.

VACK: Yeah. Like, the movie comes out and there’s a lot of love on Letterbox, but then there’s also haters that write these paragraphs and that always thrills me.

CASH: Do you have a higher power when you need to lean on something outside of yourself?

VACK: I do. I love the idea of God but I’ve never been able to really get down with any of the dogma of established religions. I’m a coexist guy. Interfaith.

CASH: You should get a bumper sticker.

VACK: This is a crazy thing to put on the record but I did not get the part of Jesus. They all loved me. Sadly, they Googled me and saw that I’d made a movie called Assholes and had a meme page called The Master of Cum. But I bring it up because getting to play the part of Jesus would be so beautiful. I love Jesus the man so much. That’s the beauty of being an actor—embodying any character is very powerful.

CASH: I always find it inspiring how much Jesus accomplished at such a young age.

VACK: A high achiever.

CASH: Do you know who got the part?

VACK: Some actor from the UK.

CASH: A British Jesus?

VACK: No comment.

CASH: Is there anything that you’d like to say, apropos of nothing, on the record?

VACK: One thing is, [Sillyboy] took a lot of effort. I worked so hard on it. And if people feel it was low effort, let it be known, it wasn’t.

CASH: What was the editing process like?

VACK: Jon [Lindsey] and Nathan [Dragon]’s notes were some of the best I had. We talked a little bit about this in our failed first interview—I do come at this as an outsider. Their notes were sensitive and beautiful and I wrote one more chapter based on their suggestions.

CASH: I just got my book edits from FSG and I haven’t opened them. I didn’t think that I would be so squeamish about it.

VACK: When you’re writing something, do you write every day or do you write in spurts?

CASH: I get really obsessed and I’ll write in long marathon stretches.

VACK: Same. Are you able to figure out what notes you should take and what notes you shouldn’t?

CASH: Discerning that is really difficult. It’s the same with criticism. What you should take seriously and what you should let roll off your back. Listening to too many voices can be dangerous. Then you get kind of trapped. The other day, Levi was telling me about how they keep the elephants from escaping in the circus—so when they’re baby elephants, they put a ball and a chain on their foot so they can’t get away. And then when they grow up, they could easily break the chain and escape, but because they grew up thinking that they had only so much leeway, they don’t even try. So I guess I wanna make sure, as I grow up as a writer, that I’m still able to break away and subvert and change how I write and not just stay in the circus forever.

VACK: You said that you see Earth Angel as confessional. I saw it as high-concept.

CASH: I just borrowed a lot from my life. How do you feel about the write what you know rule?

VACK: I feel you’re always writing what you know no matter what. I say this as someone who’s gone through a lot of angst around this topic, but I want to become someone who doesn’t think and more follows instinct. Like, it doesn’t matter if it’s based on something I’ve been through or not. Right? Am I missing something from that argument?

CASH: I’ll try to write what I don’t know because I don’t necessarily have a story of profound value. Like, I didn’t escape apartheid as a child. I live a somewhat mundane existence. That said, a good writer should be able to write about paint drying.

VACK: Yeah. I struggled a lot with this feeling when I was writing [Sillyboy] because I knew I was writing about stuff that wasn’t capital-P profound. In fact, I was writing about very mundane problems that are not moving mountains. They’re just normal relationship problems. I love stuff like that. I really love watching rom-coms—watching the dysfunctional. I love Sally Rooney. I love Philip Roth. He uses autofictional elements to talk about greater themes. The world needs all different kinds of things.

CASH: In Sillyboy, you write from the perspective of Chloe for a bit. How was writing as the opposite gender?

VACK: I think I may have enjoyed doing that more. It’s a release, an escape. In my films, I’ve written too many characters from the female perspective and I sometimes wonder if that’s a protection method. Maybe it’s easier to be honest if I’m gender-bending. I really love women, like a huge fan of girls. I feel like historically I have gotten along better with women, so I guess there is a part of me that gets off on trying to do that well.

CASH: Did you discover anything about yourself while writing Silly?

VACK: That’s a good question. I was kind of processing my own frustration and trying to say something about anger issues, something that’s very male and hard to talk about. This innate rage in men that probably relates to hunting and gathering. It’s extremely taboo in society now.

CASH: Say more.

VACK: When you’re not obviously condemning it, it’s going to draw negative attention. But I do think there is an anger and a rage in men that’s not toxic. And men won’t move forward or get better or figure out how to deal with women or themselves without books that cover this.

CASH: There was, I think it’s David French, some little piece in the Times the other morning about when Hulk Hogan ripped his shirt open at the RNC and how this is the projection we give to other countries about American masculinity and how there isn’t a lot of ink spilled about what it is to be a straight male right now. There’s these two modes: you can be a cuck or you can be ripping your shirt off at a MAGA rally. And there’s not a lot of rhetoric about that liminal in-between.

VACK: We’re caught between GigaChad and Cuck. Guys today have to go to militiamen MAGA country to shoot all their aggression through their AR. I don’t know, the men I see are really perverted by anger in really weird ways.

CASH: Do you have a solid male friend group?

VACK: I do now. I relate to guys who get their aggression out through their work, who allow themselves to say and do taboo things through their work. Those guys are calmer and actually more gentle than guys who don’t do that.

CASH: They’re processing and analyzing.

VACK: It’s a line in my movie: “It’s called being an edgelord and it’s the most honorable thing you can do with your life.” And I know there’s a lot of anti-edgelord sentiment, but I will ride for that kind of expression forever. It’s the release valve for taboo subject matter and anger in society.

CASH: Do you look up to your father?

VACK: So much. He’s my role model and he’s the best guy. I am very blessed to have my father and mother. I do have a very strong male role model and I’m lucky for that. That’s a privilege. As you know, there was a psychoanalytic atmosphere in my family because my mother is a psychoanalyst. I have had an analyst since I was 17. And that’s been the culture of our family. Psychoanalysis is about speaking taboos.

CASH: How did your parents talk to you about sex growing up?

VACK: My sister was always very open with them about sex. I’m actually not that big of a sharer with them. I don’t really talk about that with them at all. I grew up in the city around sophisticated kids. I remember people talking about very hardcore shit when I was a little boy with all my advanced friends. But I think people have this misconception about the Brown family because we’ve made these provocative artworks together. People think sex is very much the subject matter in our family, but it’s really not. I actually feel very prudish around my family.

CASH: Something you are commended for in what’s an otherwise terrible review are the sex scenes in your book. American media is very sterile and prudish. And you tap into eroticism artfully—like, sex is a part of life and it’s not always polished. Sometimes it’s weird or gross or boring.

VACK: Right? American culture is in a kind of sex-negative mode. Intimacy is where art becomes the most interesting to me. I’m much more into intimate relationship stories than grand philosophical ideas. I used to have this ego-ist desire to see myself as smart and would only care about dense writing, but I just find much more value in stuff about relationships and people. And if any greater idea gets communicated, I would much prefer that to be the side dish and not the main course. Sex is a part of life. We’re all thinking about it and doing it and I could never conceive of making something that was prudish. It just wouldn’t come naturally to me. I didn’t try to get this book published on a big press so I didn’t have the same limits as you, and I admit it’s a bit of a luxury. It afforded me a lot of freedom. I wanna ask you this, even if it’s off the record. Has that come up at all? Because I see you as someone who is permissive. You’re basically based, in my mind. Like, “Huh, I wonder if Madeline wrote stuff in Lost Lambs that’s going to ruffle feathers.”

CASH: I’m early in the editorial process but it sold commercially as is. And it has a teenager dating an ISIS recruiter and a cabal of gay billionaires and a lot of human trafficking.

VACK: But that seems pretty structural. How could they take that away from you? Do you have any slurs in the book? What’s the worst word you have in the book?

CASH: Um, there is a brain-damaged girl who is called retarded. But I’m not calling her a retard. The characters are. She’s actually a pretty big, fleshed out character.

VACK: Have you gotten in trouble before?

CASH: I’ve been called fetishistic.

VACK: But what is a writer if not a fetishizer? How could you be an artist without fetishizing? I am pro-appropriating. You know what I mean? Culture should cross-pollinate.

CASH: Do you like how your career and professional life look right now?

VACK: I do. I always close out my acting classes admitting to the students how challenging it is to be an actor or writer or filmmaker. There’s so many barriers. And I always talk about how you need to tell yourself a positive story about yourself and your journey, and that you have to be feeding yourself positive thought-food to keep going. But I say that as someone who struggles with it.

CASH: I struggled with the accept the things you cannot change part of the serenity prayer, because I want to control everything, curate the narrative around myself and my work and my artistic persona. Letting the chips fall where they may is a big part of being an insert actor/writer/filmmaker.

VACK: Yeah. You have to just sign up for all of it.