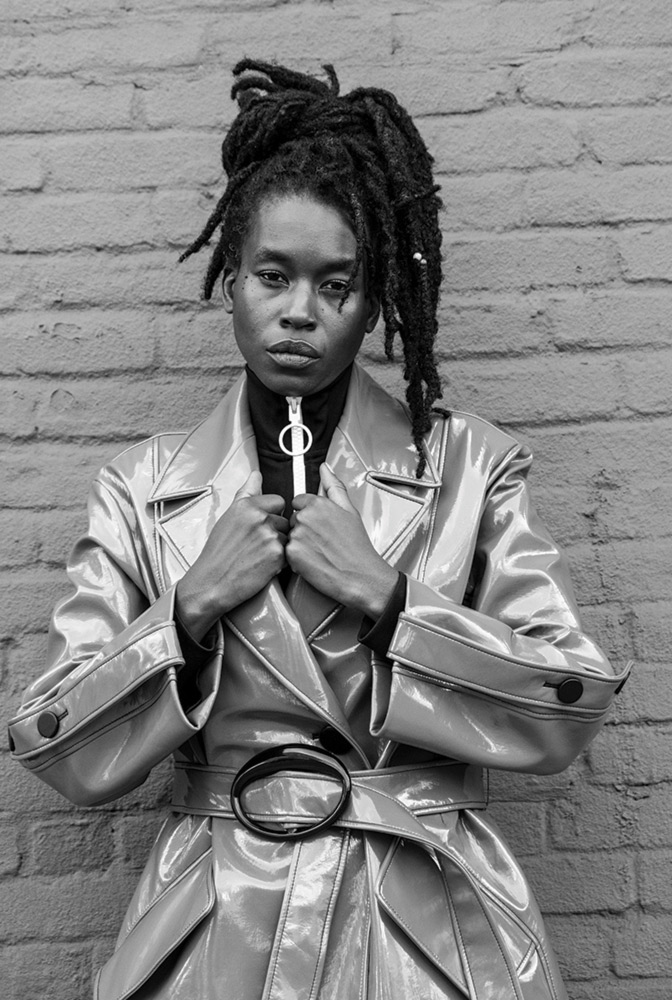

Performance artist Moor Mother isn’t afraid of confrontation

Surrounded by computers, effects pedals, and noise-amplifying gear, Camae Ayewa—the artist more commonly known as Moor Mother—cuts an imposing figure onstage. Gripping a microphone and obscured behind a tangle of black dreads, Ayewa toes the line in performances between spoken-word poetry, public exorcism, and jet-engine levels of manicured sound. Her music, composed of intricate sonic collages and looped vocal incantations, is by turns beautiful, frightening, and much like Ayewa herself, wholly unpredictable. “It differs from night to night,” she says of her often confrontational shows. “Sometimes I don’t even look at the crowd at all. Then sometimes I want to get them. Things they do annoy me. Sometimes I’ll just leave the stage, and smack a beer out of some guy’s hand, and get in people’s face. Mostly I just want

to focus on the feelings that I’m trying to get across.”

Born and raised in Aberdeen, Maryland, Ayewa has spent the better part of the past decade working along the fringes of Philadelphia’s DIY art and music scenes. In addition to her poetry and zine-making practices, she also serves as one half of the Black Quantum Futurism Collective, a freewheeling art group exploring the intersection of creativity and community activism while laying out their own take on Afrofuturism. It’s a mode of thinking that deeply informed the making of Ayewa’s first full-length album, 2016’s Fetish Bones—a densely layered industrial mélange of drones, delicate synthesizer tones, and graphic lyrics. “Use my dead body as a raft to survive the flooding that’s coming,” she intones on the closing track.

Last April, she received the inaugural Emerging Artist Award from New York’s experimental performance space the Kitchen. As a result, Ayewa is finishing a new body of work for her solo exhibition there this spring that showcases her music, writing, and a variety of installations involving sound, mirrors, and film. For someone whose art routinely explores ideas of queerness and the history of the black experience, the institutional support is both unexpected and welcome. “I feel like I’ve been working for a long time to get to say what I want to say,” she says. “I drooled over certain synthesizers for years. Every day, I would check them out and think about what I could do with them.”