Paula Cooper

“I think I’m always optimistic about art, because what would happen to us with out it?” -Paula Cooper

In October of 1968, Paula Cooper opened her eponymous gallery at 96 Prince Street in New York’s then-desolate SoHo neighborhood. Her first undertaking was an event called “Benefit for the Student Mobilization Committee To End The War in Vietnam,” a now legendary exhibition that included works by Donald Judd, Robert Ryman, Carl Andre, Jo Baer, Dan Flavin, and Sol LeWitt, among other artists (a number of whom Cooper would eventually come to represent). From this auspicious and audacious beginning, Cooper has, over the ensuing 40-plus years, continued to support not only the social and political causes she believes in, but also a truly idiosyncratic group of people whose work she has helped achieve wider acceptance. Her historical roster has included such luminaries as Lynda Benglis, Jonathan Borofsky, Elizabeth Murray, Robert Wilson, Robert Gober, Sherrie Levine, Christian Marclay, Rudolf Stingel, Kelley Walker, and, as a recent addition to her gallery’s ever-eclectic program, Tauba Auerbach.

Throughout Cooper’s influential career, the art world has both rapidly expanded and suffered the indignities of multiple financial crises, but all along, she has maintained her independence and brought an unusual degree of integrity to her dealings with artists and the public alike. At age 74, she is in many ways an unconventional icon among art dealers. Her holistic approach suggests that a gallery might be more than merely a commercial enterprise—that it might also play a larger role in the community, an idea evidenced by the many benefits she has hosted over the years for organizations ranging from the Professional and Administrative Staff Association union members of the Museum of Modern Art to Amnesty International and the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. Recently Cooper sat down on two different afternoons—the first in her Chelsea apartment, the second in her West 21st Street gallery—to talk to me about her life working alongside artists and her persistent optimism for the world of art.

MATTHEW HIGGS: You once said, “All I wanted was to be independent. I think the most important thing in life is to be able to do what you want to do—and I am.” This was a quote from 1989. Do you feel the same way today?

PAULA COOPER: Yes, I still feel very independent. I suppose the only thing that has changed is that I’ve become more . . . Well, I don’t want to say tougher or more careful . . . But the art world has changed a lot from when I started, so there has been a slight shift in my attitude. My basic attitude is still the same: I’m interested in doing what I do. I generally want to work with artists who need someone to work for them. When I started working with Don Judd, whom I had known from the very beginning of my time working in art in New York, he really needed my help. He was nowhere. I loved his work so much that I wanted to be involved with it. What really motivates me is living with art—being intimate with it. I once had an incident with an artist who had become quite well-known. He started to bring his lawyer into negotiations because he thought I was too innocent and open. I said, “If I have to work any other way, if I have to be suspicious and bring a lawyer in all of the time, then I don’t want to work that way.”

HIGGS: I know that when you were a child your father worked in the Navy as a social worker, and you moved around a lot. I read somewhere that you attended eight different schools by the time you were a teenager. People have linked this instability to your subsequent independence as a dealer. But I find an extraordinary stability throughout your career, especially in the operation of your gallery. Do you plan ahead?

COOPER: I don’t plan. I’m really bad about planning, especially when it comes to working with artists. If an artist can’t do something on a given date, I accept that. It doesn’t make me upset. I keep some space open throughout the year because something wonderful might come up, and I want to be able to work that in.

HIGGS: It seems like that was always the case. You opened the Paula Johnson Gallery in New York in 1964. And then you worked at Park Place [Gallery] near Washington Square Park between 1965 and 1967, which was an artist cooperative supported by a number of collectors. Park Place was not only an experimental model, but judging from the community of artists involved— Robert Grosvenor, Mark di Suvero, and Forrest Myers, among others—it seemed utopian.

COOPER: Yes, definitely.

HIGGS: How did that experience inform the opening of the Paula Cooper Gallery in SoHo in ’68?

COOPER: Well, when I had my first little gallery in 1964, Paula Johnson, which was really half-assed, I was running it out of the house I lived in across the street from Hunter College. There was a man I knew quite well named Steve Pepper. He had an art space on Broadway that was much more of an open situation than the rigid commercial-gallery setting. We got along very well and I met a lot of artists through him-not artists who I necessarily ended up working with, but a community nonetheless. So when I started working at Park Place, I was very open to what the artists were doing and what they wanted, and I really enjoyed being there. It was a very generous way of working with art. The Park Place artists were very open to bringing in other artists who were not members of the collective. Leo Valledor, for instance, invited Robert Smithson and Sol LeWitt to show with him, and at that time, these artists weren’t so well-known.

HIGGS: So Park Place was breaking with the rigid format of a gallery where they exclusively represent a fixed stable of artists.

COOPER: Exactly. They also created a space at Park Place where artists could present their models for large-scale sculptures and projects that they had in mind or that they hoped to get commissioned. Ronald Bladen had mock-ups there, as did other artists who did not belong to the Park Place group.

HIGGS: Were there any other examples of artist collectives operating like this at the time?

COOPER: Other places like Park Place? Not that I know of.

HIGGS: Here is a quote I found written by Peter Schjeldahl in 1969 about the Paula Cooper Gallery: “The Cooper is, if you will, an ‘activist’ gallery, aiming to reflect and influence the actual production of new art as much as its acceptance by critics and collectors.” I thought that was an interesting statement for the time. I’m interested in this use of the word activist.

COOPER: I think he meant in terms of production and viewing art.

HIGGS: Do you see that as being different than activist in a political sense?

COOPER: Not at all. It was political. My first show at the Paula Cooper Gallery was an anti-Vietnam War show.

HIGGS: Not only was the gallery politically minded, but you also embraced other disciplines such as dance, music, and literature. That must have been quite unusual at the time.

COOPER: I have such an enormous respect for all the arts. For example, I think Merce Cunningham is one of the greatest artists I’ve ever had the privilege of meeting. So I thought, I have this space, why not put it to good use? Bringing in different kinds of artists was good for the space.

HIGGS: Thinking about what is “good for the space” is a very different approach to the conventional model of a gallery. It seems you were creating a social and political context for the art you were interested in—something more than the gallery just being a container or receptacle. I came across a description of your gallery by Robert Stearns where he called it “a community of ideas.” That is such a poignant idea for what a gallery might be.

COOPER: Robert Stearns went on to become the first director of the Kitchen. It wasn’t me alone. Holly Solomon also had a very performative space downtown. I think the idea was to be open to things, open to happenings, and I was very curious. It’s actually funny thinking back because I’m also quite a controlling person.

HIGGS: Is that a paradox?

COOPER: It’s great that it could happen! And a lot of it has to do with the fact that artists came to me and asked to put these things on. I think the first performances we did were with the experimental theatre company Mabou Mines, and Philip Glass did the music. Their idea was that they would present the performances in the gallery before they ever brought them to a theater.

HIGGS: As a kind of work-in-progress?

COOPER: Yeah. I always thought that for space to be valuable it should be used by artists of all disciplines.

HIGGS: Thinking back to that first show protesting the Vietnam War, it draws a lot of parallels with today’s art world, specifically in light of the Occupy movement. Once again people are questioning the role of the artist in relation to social and political events.

COOPER: I think the artists that we work with now are, in fact, much more openly political. Hans Haacke always has been. And there’s Walid Raad, Sam Durant, and Carey Young. But truthfully, I don’t believe in political art. I believe in art!

HIGGS: You opened the Paula Cooper Gallery 44 years ago. Could you imagine just starting out and opening an art gallery in today’s climate?

COOPER: Maybe I wouldn’t open a gallery. Maybe I’d just have a bookstore. I’m just so involved with the artists now. I’m too involved not to be involved. But then again, I was also very discouraged about the art world when I was a young woman.

HIGGS: It was quite an all-male club in the 1960s New York gallery world. I’ve read that there was a condescending attitude toward you at the time, as well as to other female art dealers.

COOPER: Yes, but it was a very, very small world back then. So, by nature, it was very closed. And that had something to do with the economy of the galleries, which was also so much smaller than it is now.

HIGGS: Here is something you said in 1989: “It’s different for younger artists. There’s an enormous amount of pressure on them to produce. And the scene is so political today and more about money than it ever was.” The late ’80s were when the financial markets were crashing. It’s an extraordinary statement because it could be applied as much to then as to today.

COOPER: What’s different today is that the artists have taken charge of their careers. They have all these assistants in their studios and they know and talk to people directly. The general notion before was that the artists should be free to work and not contend with all of the rest of it.

HIGGS: The gallery dealt with business?

COOPER: Exactly. So this idea of control has changed. And a lot of times the artists have really screwed things up. [laughs] But today some artists are making so much money, and when it gets to be about money, that’s when it gets difficult.

HIGGS: So how, on a day-to-day basis, do you deal with running a very high-profile gallery in New York, home to the biggest art market in the world?

COOPER: But we’re very small! We’re no Gagosian. We don’t have those ambitions. We have different goals.

HIGGS: How would you characterize those goals?

COOPER: I want to help artists to get there, to be able to work and to be recognized. It may sound silly in this day and age, but I’ve always thought, If you want to make money, you can make money. You can devote yourself to that. But it’s never been a priority for me.

HIGGS: Or for your artists?

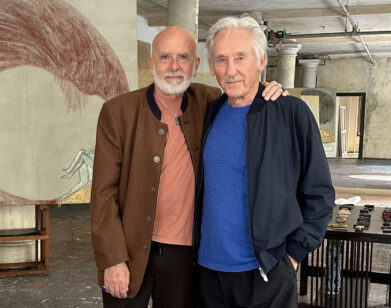

COOPER: I mean, look at Robert Grosvenor. He’s 70-something years old. We’ve been working together since our time at Park Place. He is being recognized a bit now, and it’s thrilling! The Whitney Museum bought this piece of his in the 1960s, but they didn’t show it at the time; they put it away, it was deteriorating. This was more than 40 years ago. And now he’s having success. I said to Bob the other day, “Look, if you live long enough . . .”

HIGGS: I think one of the most interesting things to happen in the art world over the past decade has been the reevaluation, reappraisal, and rediscovery of significant artists from the past 30 or 40 years. Artists whose work has, for one reason or another, been overlooked or neglected. Robert Grosvenor is a great example of that process. But it’s also interest- ing that in the past few years many young artists have joined your gallery-including Kelley Walker, Sam Durant, Paul Pfeiffer, Carey Young, Walid Raad, and, recently, Tauba Auerbach. How did the conversations with these younger artists come about? Do you see a relationship between their approach and that of the artists you’ve worked with for decades—artists such as Mark di Suvero or Carl Andre?

COOPER: I don’t see their work in relation to each other. I don’t compare it at all. My relationship with each artist is quite different. In the past year I’ve actually become more interested in getting closer to these younger artists—just spending time with them, talking to them.

HIGGS: Much as you would have done in the early days with the artists you started out with?

COOPER: Yeah, but it’s very different! Those artists were my peers in those days. Now, I could be some of these artists’ grandmother. Seriously. And they are all very different. Someone like Walid [Raad] is very international; he speaks several languages, he is aware of so many different cultures. And then there are other artists who were exposed to much less early on, who only had doors open for them when they became an artist. Usually when someone makes a work, we only understand it from our own point of view. One thing about working so closely with artists is that you learn a different point of view and see how your own interpretation is not necessarily the only one.

HIGGS: How do you embrace the fact that your gallery and many of the artists you have worked with have become historical? I understand that you gave your Park Place archives, and also the archives of the Paula Cooper Gallery from 1968 to 1973, to the Archives of American Art. I thought it was an interesting way of jettisoning the past.

COOPER: Only up to 1973, though—I’m hanging on to the rest! My attitude for keeping my archives after 1973 is that time goes by so quickly. It’s amazing to me to think of that time as historical now. It’s part of my life. It’s very important and something that lives with me. So I’m loath to give it away. In keeping the archive, I’m hanging onto my life in a way. I know everyone else at the gallery thinks, “Let’s get rid of these old records! Let’s get rid of these books and photographs. We need more room!”

HIGGS: Your relationships with some artists go back more than 40 years. I was thinking specifically about Carl Andre, who will have a career retrospective at Dia [Art Foundation in New York] in 2013. How did you first come across his work?

COOPER: I was going to galleries with Walter De Maria and saw Carl’s Equivalent works at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery. I was just so mesmerized. I didn’t want the experience to end. And 40-odd years later, I still feel that way about Carl’s work. I still think he’s one of the most radical artists there is.

HIGGS: When you saw the work at Tibor de Nagy, you weren’t working with him at that time?

COOPER: No. I never dreamed that I would eventually be working with Carl. I just admired his work so much, and then I met him at Park Place. He used to come to Park Place, as his wife at the time was Rosemarie Castoro, and she was often in group shows there. So that’s how I met him. And then oddly we were both invited to speak on a radio program. All I can remember is that for some reason we ended up talking about Soviet bridges. I don’t know what that had to do with anything.

HIGGS: Did most of your longtime working relationships with artists evolve out of what began as informal conversations?

COOPER: It did with Carl, and with Sol LeWitt, too. Sol’s work changed a great deal over the years we worked together, and so did some of his ideas. Maybe we could have parted at some point. But I just continued to have the same level of interest in everything that he did, and I was so amazed that he was so free. Sol just loved working, and he just worked and worked. He was not at all self-conscious.

HIGGS: You wouldn’t use similar language to describe Carl’s approach?

COOPER: No. Carl’s methodology is perfection, I would say. [laughs] You know, he still makes . . . I don’t like the word still.

HIGGS: Continues?

COOPER: Right. He continues to make the most perfect work.

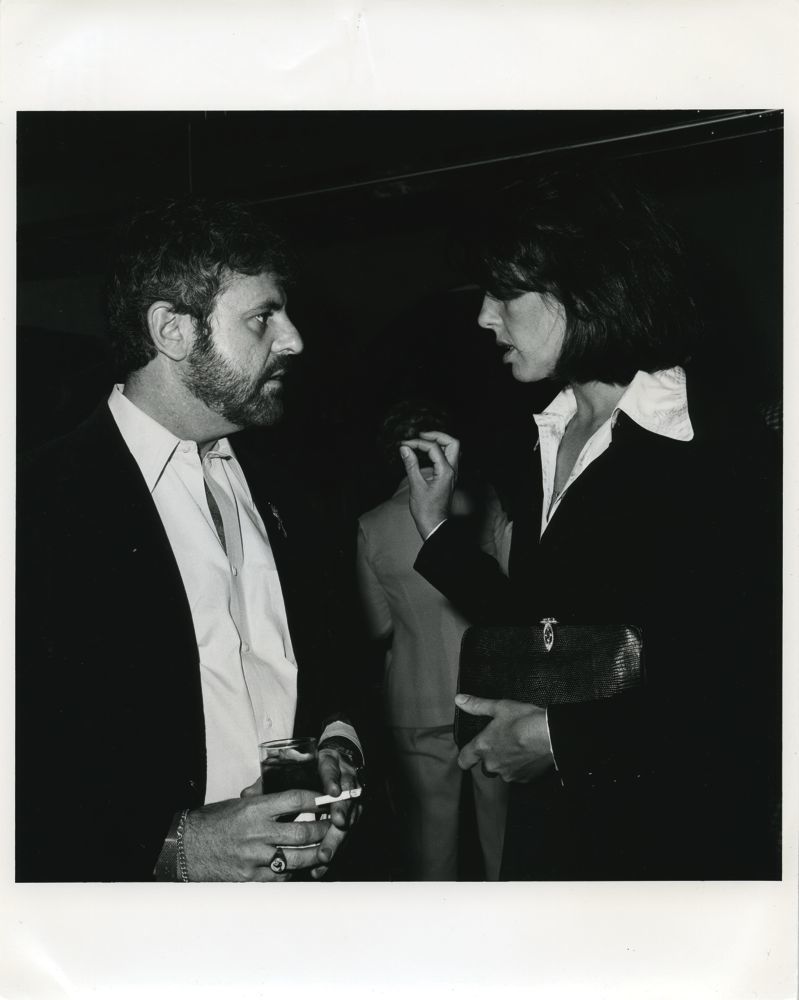

HIGGS: Can we talk about Rudolf Stingel’s 2005 show at the gallery? He presented a monumental painting of you based on a 1984 portrait taken by Robert Mapplethorpe. It remains one of the most remarkable exhibitions I’ve seen. You are quite a private person, and you have maintained a low profile when it comes to public life, so I was curious to know how it felt to present a monumental portrait of yourself to the public for the duration of the show’s run?

COOPER: I didn’t know what Rudolf had planned for that show. All I knew was that we had to get white paint from Italy because he wanted the space to be all white. But I did not know what he was going to show practically until it happened. It was most embarrassing. And it’s a terrible thing to have people say, “Oh, you used to be so good-looking!” [laughs] And you think, Oh, god. Every day of that show I would sneak in and just go upstairs to my office.

HIGGS: What happened to that painting? Did a collector acquire it?

COOPER: No, he wouldn’t sell it. Although someone did want to buy it.

HIGGS: We talked a little bit about the chauvinism in the art world when you started out. One thing that characterizes the art world of the last 20 years is, perhaps, the proliferation of female art dealers.

COOPER: There were a few female art dealers in the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s who were very successful. But when I started out, the really influential dealers in New York were people like Leo Castelli and Sidney Janis. I think women have become very powerful in galleries these days. Marian Goodman is untouchable, and there’s Barbara Gladstone. It’s like women in politics, who, in order to succeed, have to be more like men in their agenda.

HIGGS: That wasn’t the case when you were starting out?

COOPER: Not at all. That’s changed. HIGGS: Is that an improvement?

COOPER: [laughs] No, I don’t think it is!

HIGGS: Quite soon the Paula Cooper Gallery will be 50 years old. How does that feel?

COOPER: I can’t believe it. That’s my reaction. I just can’t believe it.

HIGGS: Are you optimistic about the future for both art and the art world?

COOPER: The art world has changed so much. It’s so international these days, and it just seems so endless and huge. I don’t know how one can handle all of this information. There’s so much to see and so much to think about. Sometimes it just seems so overwhelming, but at the same time, it’s incredibly interesting. I think I’m always optimistic about art, because what would happen to us without it?