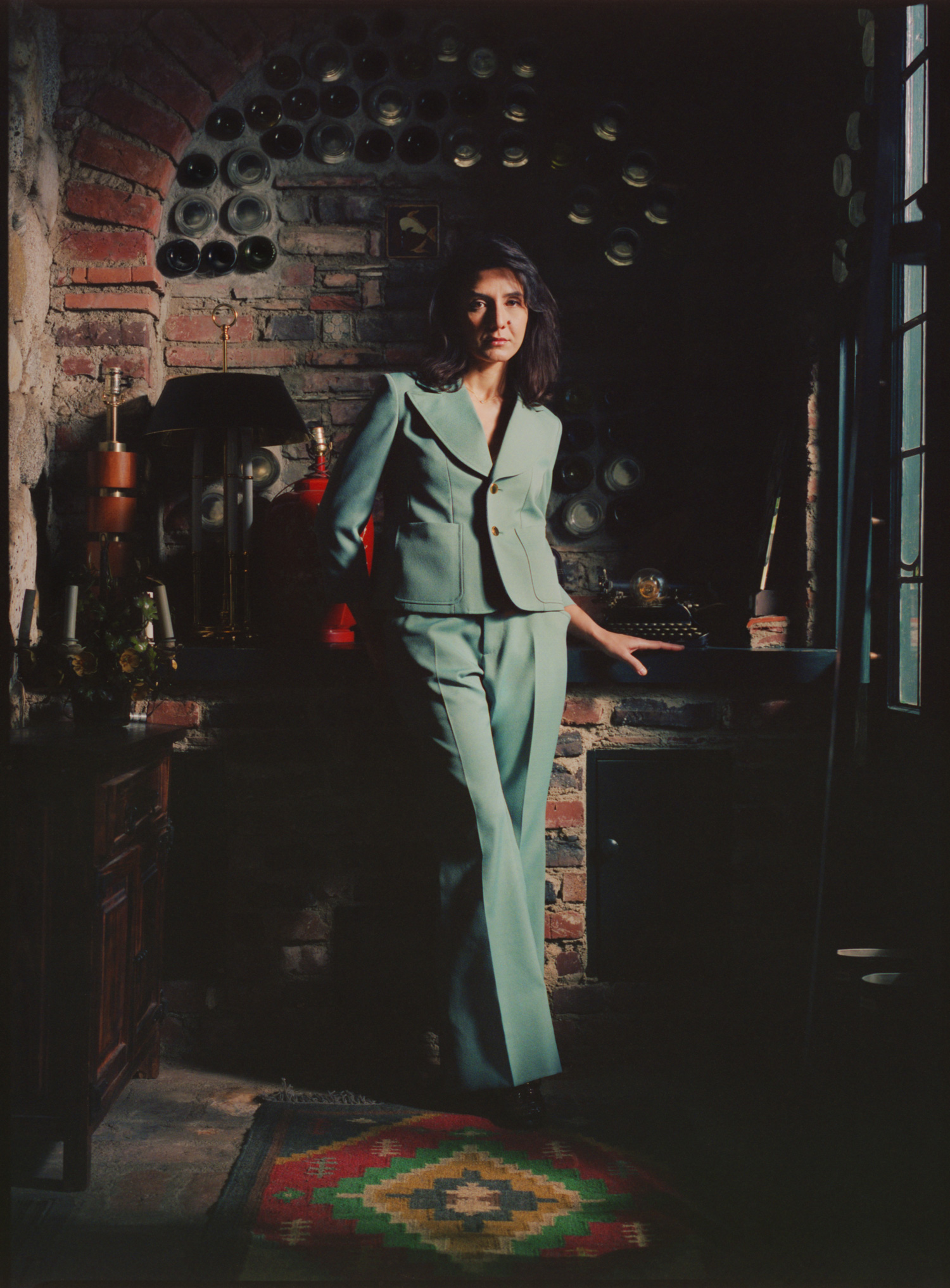

Ottessa Moshfegh’s Year Has Been Neither Restful Nor Relaxing

Shirt by Gucci.

In our fractured, discordant, don’t-speak-for-me present, there stands little chance that any one author could represent the spirit of the age. But Ottessa Moshfegh would be a strong nominee for those in search of a young literary polestar. A daughter of musicians, the 38- year-old novelist attained cult-writer status in the mid 2010s, publishing a novella, a novel, and a short-story collection. But cult interest turned out to be a mere pit stop. After releasing her dark and hilarious emotional barbwire of a novel, 2018’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, about a privileged 20-something Manhattanite drowning in prescription pills, Moshfegh became a star. The novel was so smart and daring that it was passed among friends with the promise that it contained essential, unkind wisdoms.

This month, Moshfegh’s third novel, Death in Her Hands (written, in fact, when her first was still getting ready to come out), arrives on bookshelves. It’s a sort of murder mystery, but in Moshfegh’s weird and wonderful hands, it does not unravel like a typical genre story. Rule one of a mystery: Start with a dead body. Moshfegh starts instead with a note found in the grass announcing that there has been a murder (the body of the young victim, named Magda, is nowhere in sight). It is the fate of an elderly widow, Vesta, to come across this ominous revelation on her daily walk with her dog, and from there her already shaky life turns upside down as she searches for answers. It’s as if the postmodernist writer John Barth wandered into an Agatha Christie whodunit. Moshfegh herself is a wanderer, having lived multiple times on both American coasts. Now settled in Los Angeles, she stopped by the Mid City studio of her friend, the artist Alex Israel, to talk about strange animal visitations and writing about the dead.

———

ALEX ISRAEL: Have you had any recent, noteworthy L.A. adventures?

OTTESSA MOSHFEGH: My friend Matthew Lessner and I were out at coffee and we decided to go for a hike, because I had my dog with me. Matthew is a filmmaker, and his imagination is, like mine, on the creepy side. We drove to this place in Highland Park to hike and, pulling up, I saw these women in exercise clothes looking through a chainlink fence. They left as we parked, and we walked over to where they had been standing. Then I saw something. I was like, “Oh god, please don’t let that be a dead dog.” Instead it was a headless goat.

ISRAEL: A real one?

MOSHFEGH: Yeah.

ISRAEL: Are you making this up?

MOSHFEGH: No! I have a photo.

ISRAEL: I don’t want to see it. Do you think there had been some kind of ritualistic sacrifice?

MOSHFEGH: I think it was exactly that. A couple of yards away there was a cardboard box with a chicken in it that was also dead. I went online to notify animal control, but a report had already been filed. Someone had beaten me to it. This happens quite often, apparently, people finding headless goats. And there are a lot of articles about why we shouldn’t be prejudiced about it. Like, it doesn’t mean it’s satanic.

ISRAEL: Were there flies?

MOSHFEGH: No, it was brand new.

ISRAEL: What did your friend think?

MOSHFEGH: He took a picture of me inspecting the headless goat through the fence. And then we went on our hike.

ISRAEL: Okay, maybe now I want to see the picture.

MOSHFEGH: It was right after New Year’s Eve, so maybe it was part of a cleansing ritual. It also happened to be right around my wedding anniversary.

ISRAEL: Didn’t you meet your husband [the writer Luke Goebel] when he came to interview you for a magazine? You guys fell in love that day, and he has the whole thing captured in a recording of the interview.

MOSHFEGH: Yeah. It was for The Los Angeles Review of Books, but they didn’t end up publishing it. We got engaged almost immediately—like six weeks in. Then we got married two years later.

ISRAEL: How many dates did you have before you got engaged?

MOSHFEGH: We didn’t have a date. He came over and we were just together forever. I don’t know if I would have had the patience and strength to “date,” if it had come about another way.

ISRAEL: So, your wedding anniversary lands around the same time as this ritual sacrifice. And it’s also the Year of the Rat.

MOSHFEGH: I will tell you a weird anecdote. Luke and I went on a hike on this really big mountain near Pasadena last December. Luke went up ahead and I was alone on these hairpin curves, when suddenly I heard this chirping. It was really, really loud. I looked down and there was this newborn mouse about an inch-and-a-half long, completely pink, totally hairless. Its eyes and ears were sealed. It had little feet and a very cute face, and it was screaming and all alone. It was like someone had put it there for me. So I picked it up and called for Luke. It had zero chance of survival. I don’t know how it got there. I guess it fell out of a nest or got abandoned. It was just so weird.

ISRAEL: Maybe it was the runt of the litter.

MOSHFEGH: Who knows. It was my first encounter with something that new and needy and vulnerable. Luke was a bit hesitant, but we ended up taking it home and we tried to feed it kitten formula with an eyedropper, which is what you’re supposed to do. We weren’t even sure that it was a mouse.

ISRAEL: It could have been a rat.

MOSHFEGH: Or a squirrel—any kind of rodent. And then I was on the phone with my dad the next day and Luke was trying to feed it and it died. We were so sad. I still miss it. Then on Chinese New Year’s Eve, I found another mouse, but that one was full-grown and I think it had eaten rat poison, so Luke had to kill it, which felt like both a sacrifice and an act of kindness.

ISRAEL: Do you see a lot of wild animals out where you live in Pasadena?

MOSHFEGH: There are a lot of birds and squirrels. When we first moved, people were telling us that there were a lot of coyotes. Sometimes we hear them.

ISRAEL: I see coyotes all the time. The main character in your new novel also takes interesting walks in nature. How did Death in Her Hands come about?

MOSHFEGH: I started writing this book when I was waiting for [Moshfegh’s first novel] Eileen to come out in 2015. I was living in Oakland, California, by myself. I was about 32 or 33, so I was having a Jesus-year crisis, like nothing made sense. I was in a constant state of extreme anxiety.

ISRAEL: What were you doing in Oakland?

MOSHFEGH: I’d moved there to be close to Stanford because I had this fellowship. But at that point I had stopped going and was just focusing on self-care. I was in really intense therapy. And I knew I didn’t have the wherewithal to start a new project that was going to be something that I would have to plan out or would become a reflection of my life over a number of years, which novels tend to be. But I still wanted to write something. So I decided to write a book. I didn’t know what it was going to be, but I was going to write at least 1,000 words every day until it was over. That’s how it started. I never planned any part of it. I never knew where I was going. I wrote it in the present moment.

ISRAEL: How much did it change after you finished the first draft?

MOSHFEGH: It didn’t change that significantly, but it did need a lot of editing. I didn’t look back—that was another rule I had. I could never read what I had written on any day prior. The protagonist, Vesta, narrates in the present moment according to what she’s experiencing and thinking. And that’s exactly how I wrote it.

ISRAEL: There’s a surreal quality to the book. In the past, surrealist writers and painters used tools such as stream of consciousness. In painting, it’s called automatism. But your book is surreal in that the reader is never sure what is real and what is not, or when you can rely on the narrator and when you can’t. Were you thinking about surrealism?

MOSHFEGH: I don’t know. I like surrealism as a concept but I’m not so sure it’s distinguishable from everything else anymore. Does surrealism still exist?

ISRAEL: I guess we live in a world that’s so surreal now there’s not such a clear distinction. But artists still use some of the tools of surrealism, like the juxtaposition of objects that aren’t meant to be together. Or leaving things up to chance in their work. Maybe they aren’t as radical as they were in the early 20th century, but the tools can still be useful.

MOSHFEGH: Isn’t all digital media surreal?

ISRAEL: All of it? Do you think every picture on social media or every video on YouTube is inherently surreal?

MOSHFEGH: Yeah.

ISRAEL: I don’t know if I agree. So much of that content is really direct, whereas there’s something indirect about surreal content.

MOSHFEGH: To me, YouTube in general is so surreal.

ISRAEL: It feels like a dream from the future. And, of course, dreams area big part of surrealism where you don’t really know where reality stops and fantasy begins. That’s part of the culture of the internet. Do you have vivid dreams?

MOSHFEGH: The other night I had a dream that America was occupied by a foreign military force. They went into people’s houses, so every home had a soldier, or an employee or whatever, who was keeping track of what we were doing. What does that mean? That I feel invaded?

ISRAEL: Maybe that you feel as if you are being watched or observed. I think a lot of people feel that way.

MOSHFEGH: My sister once told me something that gave me major panic attacks. She was talking about how things began to exist. She said that there was once a particle and it wanted to experience itself so it split in two. The idea is we have to create something else in order to be observed in order to exist. It’s like existence is a kind of self-observation or an observation of ourselves by others. I think that might be why we have pets. I mean, it’s a huge part of my relationship with my dog. It’s like he does something and I’ll observe it and describe it to him. And then he’s looking at me and observing me.

ISRAEL: My dog is getting old. He’s 14. I had to get those little steps so that he can walk up to get onto the bed. But something else I want to mention about your writing is how you mine cultural touchstones and bring them to the fore in uncanny ways. For example, I hadn’t thought about AskJeeves.com in a long time before it popped up in this novel. I hadn’t pondered Whoopi Goldberg’s iconicity until reading My Year of Rest and Relaxation. I’m wondering where these references come from.

MOSHFEGH: If my mainframe is a box, those ideas come from the bottom right-hand corner. It’s where I put things that have a certain resonance and weirdness that I have a particular relationship with, even if it’s just aesthetic. For Ask- Jeeves.com, I was thinking about the way we started to ask questions on the internet, as though the questions went through an old British butler. Like, “Let me go fetch that for you.” It’s a very pointed thing.

ISRAEL: That was before Google became ubiquitous. And it would make an elderly person connect with a website more, thinking a fellow elder was doing the work. The scenes where Vesta is using the computer in the library are really hilarious. Your book goes back and forth between being funny and scary and sad. It also skips around in terms of genre. Did you think about genres such as mystery or horror when you were writing?

MOSHFEGH: I really didn’t. Even when I was editing it, I wasn’t all that concerned about genre. The way I experienced writing the book is so similar to the experience of reading it, which is: “This is so close to falling apart.” Then somehow it saves itself. The book is always adapting and there isn’t some superimposed expectation of what you hope the book will accomplish, if that makes sense.

ISRAEL: Yeah. It doesn’t commit to any one archetype, so you don’t really know what to expect. I guess if you’re using some sort of formula, you can’t ever really escape yourself.

MOSHFEGH: And then you might never find yourself again. It’s like that documentary [Tell Me Who I Am] about the two grown twins, and one of them suffers a brain injury that erases his memory and the other brother doesn’t tell him the horrible abuse he suffered as a kid.

ISRAEL: Would you want to escape from yourself and never come back?

MOSHFEGH:I think I would take the risk, maybe when I’m really old. That’s part of why I like elderly characters. There’s nothing to lose. Or at least our vanity gets worn down to this very fine point that becomes pure personality rather than giving a shit what people think of us in a broad sense.

ISRAEL: People say the older you get, the less you give a shit. And maybe there comes a point where there are no shits given, no matter what. I care less what people think now than I did when I was 30.

MOSHFEGH: But how much is that a function of your success?

ISRAEL: I don’t know. I think that the more you put yourself out there, the more feedback you get. And the more different kinds of feedback you get, the more immune you get to what that feedback might say or how it makes you feel. You stop letting it have power over you. I do care about the people I love and I don’t want to disappoint them. That really hasn’t changed much. But when it comes to people I don’t know, I care remarkably less than I did ten years ago.

MOSHFEGH: Do you feel that the more you put of yourself into your work, the less of you there is left outside of the work?

ISRAEL: I think so. What about you?

MOSHFEGH: Totally. I feel so emptied out a lot. But you can replenish. You can also dig deeper. That’s what I want to do, start digging.

ISRAEL: Culture itself is a mine, and you can always keep mining culture.

MOSHFEGH: I think we have almost opposite relationships to culture. I’m kind of a control freak about what I pay attention to. Part of the reason I love hanging out with you is that my control freakishness gets suspended. I’m curious with you about things in popular culture I might not normally look at, partially because I trust you as a filter.

ISRAEL: Do you feel like your relationship to popular culture has changed since you moved to L.A.?

MOSHFEGH: I feel like I’ve seen behind the curtain. I’m working a bit in film, too, so I’m seeing the process of how something gets made and the different roles that people play. I think I appreciate an amazing movie more, knowing it took so much work and coordination. But now when I watch something stupid, I think of how many hours and human bodies went into making it.

ISRAEL: You’ve met the real people and have seen the real passion that goes into these things. That changes your relationship.

MOSHFEGH: The people who are actually behind these movies are making huge decisions about what we’re supposed to be paying attention to. I used to pooh-pooh the Oscars and I still do a bit, because it’s not so much a celebration of the value of great work but a consensus on what in the culture this Academy believes we should be paying attention to. I didn’t, for example, see Green Book.

ISRAEL: You should see it. Green Book didn’t change my life, but it’s a feel-good movie. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that.

MOSHFEGH: No, there’s nothing wrong with that. As an artist, I guess I get a little upset about awards. I feel the same about awards in literature.

ISRAEL: It’s true of all awards, because they’re reflections of a consensus. And the consensus isn’t always where we as artists are focusing our attention. It’s in our nature to do things against consensus. That’s why we’re artists

This article appears in the Spring 2020 issue of Interview Magazine. Subscribe here.

———

Hair and Makeup: Muamera Public at Opus Beauty using Charlotte Tilbury and ORIBE.

Photography Assistant: Eric Hersey