COMICS

“Do You See Him as an Incel?”: One Biographer’s Journey Down the Robert Crumb Rabbit Hole

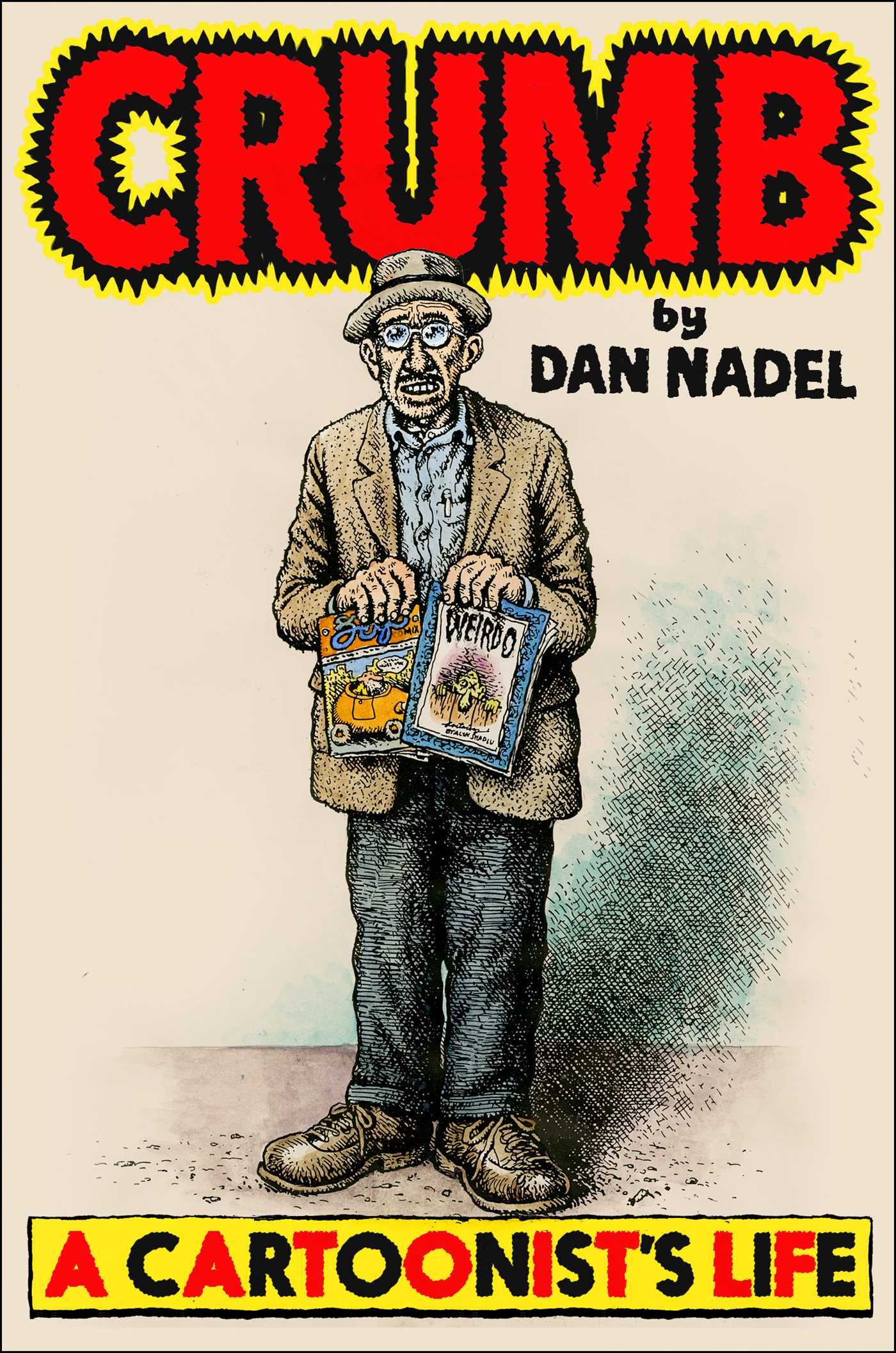

Robert Crumb, the outrageous, hilarious cartoonist whose work defined the look of the counterculture (think Fritz the Cat and Keep on Truckin’) has held up a mirror to himself and all of us for over six decades, revealing the id and superego of the American consciousness. Now, he is the subject of an expansive biography by curator and writer Dan Nadel: Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life, out this week. To celebrate the release of his book, Nadel spent a couple hours in his Brooklyn apartment with artist Al Freeman, whose artwork manifests and explores some of the same territory as Crumb’s, from the male ego to the unending flood of cultural information that she, and all of us, must contend with.

———

AL FREEMAN: Congrats on the book.

DAN NADEL: Thanks, Al.

FREEMAN: And congratulations to me for reading almost 300 pages of it, which–

NADEL: Only 300 pages?

FREEMAN: Which is a staggering achievement for me.

NADEL: You didn’t make it to page 400…?

FREEMAN: I made it to “Weirdo” and I was like–

NADEL: Did you skip to the end?

FREEMAN: No, but I know the spoilers. I know that some people die. I know that Maxon ends up on the floor eating a string. I know that Charles, you know…

NADEL: All right, you made it pretty far.

FREEMAN: I had seen the documentary, but I haven’t watched it recently because I didn’t want it to cloud my–

NADEL: No, you don’t want to cloud your judgment with that.

FREEMAN: Exactly. But I did want to ask you what your entry point to comics was.

NADEL: Wow. The entry point to comics was actually in a place called Talbots, which was a convenience store on the way to Palisades Pool out of Potomac, Maryland. It was a pool that my parents belonged to that we would go to in the summers, and I would get comic books on the way there. I was really into superhero comics like Daredevil and The Avengers and X-Men.

FREEMAN: How old were you?

NADEL: I think about six or seven. I fell into it really, really hard. By the time I was eight, I was completely obsessed with comics and with memorizing all the mythology, all the powers, understanding the whole history of these characters, and then also memorizing all the people that drew and wrote and colored the comics.

FREEMAN: There must have been a point where you went from the superhero mainstream stuff to the Crumb world?

NADEL: My entry into the Crumb world happened because, like a lot of Jewish kids, I found Maus when I was 11 or 12.

FREEMAN: Oh, that’s young to find Maus.

NADEL: I know, but I was already reading books about the Holocaust.

FREEMAN: You’re a bit of a Holocaust head.

NADEL: Yeah, instead of being really into the latest video games, it was the latest Holocaust memoirs. So, Maus made a big impression. And then I was at a comic book convention at some point, maybe when I was 12, because there used to be these great comic cons in the neighborhood. So I could walk from my house to the local Holiday Inn–

FREEMAN: To find the other nerds.

NADEL: And it was amazing. Anyway, I was milling around at the dealers and they asked me what I was into and I said, “Maus.” So, they handed me American Splendor, which was Crumb’s collaboration with Harvey Pekar, and I just loved that. I still remember all the stories in that book really well. That was my entry point to Crumb. That work made perfect sense to me visually, in my 14-year-old brain, like the sexual obsession. And after that, I found Head Comix, which is a great book. I must’ve been 14 when I found Head Comix, and it just completely made sense to me, which is weird too.

FREEMAN: It totally makes sense.

NADEL: If you’re a 14-year-old alienated kid in the suburbs and you find something that’s made by a nerdy guy and he’s having sex and it’s about jerking off…

FREEMAN: It’s the incel’s dream.

NADEL: Yes, it felt like this world of comics was available to me in the real world.

FREEMAN: You felt like there was hope?

NADEL: Oh, totally.

FREEMAN: I was never really a comic book person growing up, but I feel like I had an equivalent experience. I took art classes when I was 15 at the art gallery near where I grew up, and afterwards I would sometimes go and look in the gift shop. I remember finding a Paul McCarthy book.

NADEL: Oh my god. Great.

FREEMAN: And there was Tim-fucking-the-tree thing [Man fucking a tree, garden] and all the disgusting bottles covered in ketchup and chocolate. I was like, “Oh, contemporary art can be this.”

NADEL: Yeah I had that experience with comics, never imagining that contemporary art could be that. It’s so funny when you see that kind of thing for the first time.

FREEMAN: I think I always steered away from Crumb, just as a person learning about art and culture.

NADEL: Oh, you did?

FREEMAN: I would’ve, had I not seen him as something that arty boomer dads were into. That was what Crumb was to me. But also, I came to love all of the art that’s clearly rooted in comics. So, then going back, it was almost so weird that I hadn’t gotten into his work yet, and I was so shocked to see how much I identified with him. I related to his need to escape where he came from, his desire to satirize everything, his contrarian attitude, and his allergic-ness to convention. I was like a female incel until college. I didn’t really see any action in high school.

NADEL: I’ve been obsessed with Crumb since I was 12 or 13, but part of what let me back to him was that I could step away from being a sweaty, nerd boy for a second. I remember Mike Kelley talking about Crumb a little bit and finding my way back to it from that lens in a way, because it lets me push aside the trappings of it, the boomer-ness of it, or just the fandom that gets in the way.

FREEMAN: As someone who didn’t grow up idolizing him or comics, my mind was blown by seeing the seeds of Crumb in so much of the comedy and the art that is popular now. Even watching John Mulaney or Larry David, I can see that the Crumb character is so much a part of contemporary comedy. Playing a protagonist that is the worst possible version of yourself is so Crumb, like Louis C.K. and Larry David.

NADEL: Absolutely.

FREEMAN: And like Stavros Halkias is embracing self-loathing as a way to almost accept yourself. Or maybe it’s the double-sided coin of the self-loathing, self-aggrandizing artist persona.

NADEL: Crumb has this strange past because he was ubiquitous in the late ’60s. All the National Lampoon and Saturday Night Live writers loved Crumb. I know Buck Henry and Michael O’Donoghue were big fans. But then at the same time, we know that Woody Allen was developing simultaneously and presenting the worst version of himself and the “sex-crazed nerd.” I could imagine Crumb hitting a certain vulgar comedic sensibility, and then there’s the more intellectual comedy sensibility that didn’t have as much use for him.

FREEMAN: But getting back to the incel thing—

NADEL: Do you see him as an incel?

FREEMAN: I see him as an incel who turned it around and leveraged all of the undesirable incel qualities into something that he was able to really use to have a lot of sex.

NADEL: It never occurred to me to think of him that way after all these years of working on this book.

FREEMAN: Well, the incel thing wasn’t a conversation in our culture until recently. But now, with hindsight, it’s like, “Oh, that’s what that persona is.”

NADEL: He also definitely has an enormous following amongst men who, I guess, could be considered incel or incel-adjacent. There’s people that just post his worst stuff, like rapey-est stuff because—

FREEMAN: I think that’s some of his best work, honestly.

NADEL: The really unhinged stuff?

FREEMAN: Yeah, as someone who is repelled by moralizing culture, and as someone who likes to poke at people’s limitations. It just seems like it wouldn’t be allowed now. You say something in the book about how comics were a healthy place that he could play out these grotesque fantasies. And I think that art should be a place where it’s safe to explore some of our most vulgar desires so that you don’t end up shooting up a school.

NADEL: I mean, the ingenuity of his fantasies is astonishing. The surrealism in Crumb’s work is incredible. Because comics are a mass medium, not a painting or sculpture in a gallery, they get judged in a completely different way, as if you were in the town square. It’s subjected to a wholly different kind of scrutiny.

FREEMAN: But now his work is also being shown in blue-chip galleries.

NADEL: True, although the version of Crumb shown in galleries is a fairly sanitized one, which is understandable given the commercial context. But I think the “real Crumb” is much gnarlier than the art world knows what to do with. It resists aestheticization in the way that someone like McCarthy’s work allows.

FREEMAN: And that’s intentional on Crumb’s part.

NADEL: Absolutely, he won’t play that game, and the work itself doesn’t really allow it. Writing the book, there were times I felt compelled to defend the work rather than just put it out there and let people make up their own minds.

FREEMAN: Defend which parts specifically?

NADEL: Even just stating outright that it’s art and won’t hurt anyone. My editor wisely pushed back on that, asking if I was really sure an image of rape and decapitation couldn’t hurt anyone. A reasonable question.

FREEMAN: I think those are all fair discussions to have around the potential impact, but I appreciate the resistance to overt judgment on your part. It’s just not a conversation I find that interesting.

NADEL: Me neither. It only leads to practical matters like content warnings, not deeper insights.

FREEMAN: How did your interest in Crumb develop from discovering him through Harvey Pekar to writing this book?

NADEL: I’ve written about comics for years alongside writing about art. Crumb always fascinated me and I kept up with his work. I interviewed him in 2015 when a Zap compilation was released. And in 2006 or 2007, I curated a show of female cartoonists and met his wife Aline through that, so he remained present in my mind.

FREEMAN: And you realized that no one had written a proper Crumb biography.

NADEL: Exactly, that’s always what I look for. There had been recent biographies of other prominent cartoonists like Charles Schulz, George Herriman, Harvey Kurtzman, and while reading them I considered what I would want to do differently. I really wanted to write about the textural, tactile experience of drawing comics, figuring out printing and distribution and finding an audience. To explore all facets of it in an engaging, narrative fashion, not a dry, schematic way. Crumb fit that criteria perfectly. I knew taking on Crumb would allow me to write comics history up to a point. Initially I thought it could be a gateway to writing about his influence on contemporary artists like Mike Kelley and Peter Saul. When I first pitched it, I envisioned it almost as a cultural history. But I had to wrestle it into the shape of a narrative biography rather than just, “Here’s all this cool stuff he synthesized and the cool stuff that came out of it.” It needed a clear narrative throughline to function as a book.

FREEMAN: Well, you achieved that masterfully. I never questioned the narrative flow, but still felt I was learning so much context around Crumb’s development. The synthesis feels effortless, which impresses me as someone without a narrative brain. I

NADEL: Some people just aren’t wired that way, and that’s cool. And with Crumb, his most popular work in the galleries tends to be the non-narrative pieces.

FREEMAN: Comics do feel like such a boy’s world. I know there are many women making comics now, but reading the book, I was struck by how it barely passes the Bechdel test.

NADEL: I know, I know. But that’s the story.

FREEMAN: He had his bros and his hoes. Crumb resisted conventional relationships with women and refused to be locked down into monogamy, which feels very relevant today. I see many men in New York City acting similarly, with women agreeing to it despite not liking it. He pushed the limits of non-monogamy until someone finally said, “Enough.”

NADEL: It’s funny because normally we wouldn’t even discuss his relationships, except they’re such a big part of his work, so it’s unavoidable.

FREEMAN: And a significant part of the book, too. His move to the country compound also seems tied to that ’60s back-to-earth culture. It’s wild how long he maintained that lifestyle. It seemed violent, unpleasant, impossible to sustain.

NADEL: Absolutely. Writing about it, the franticness and unpleasantness felt so foreign to my own operating system. But Crumb’s mind was so open, I could see why the chaos made a kind of sense to him.

FREEMAN: Is it an incel fallout, going from feeling like he’d never get laid to suddenly having the floodgates open and refusing to turn off the tap?

NADEL: Yes and no. Not turning off the tap is one thing. Plotting your whole life around getting laid, taking three-hour bus rides, that’s another level of effort. He’s a compulsive guy. Records, sex, comics.

FREEMAN: Drugs too.

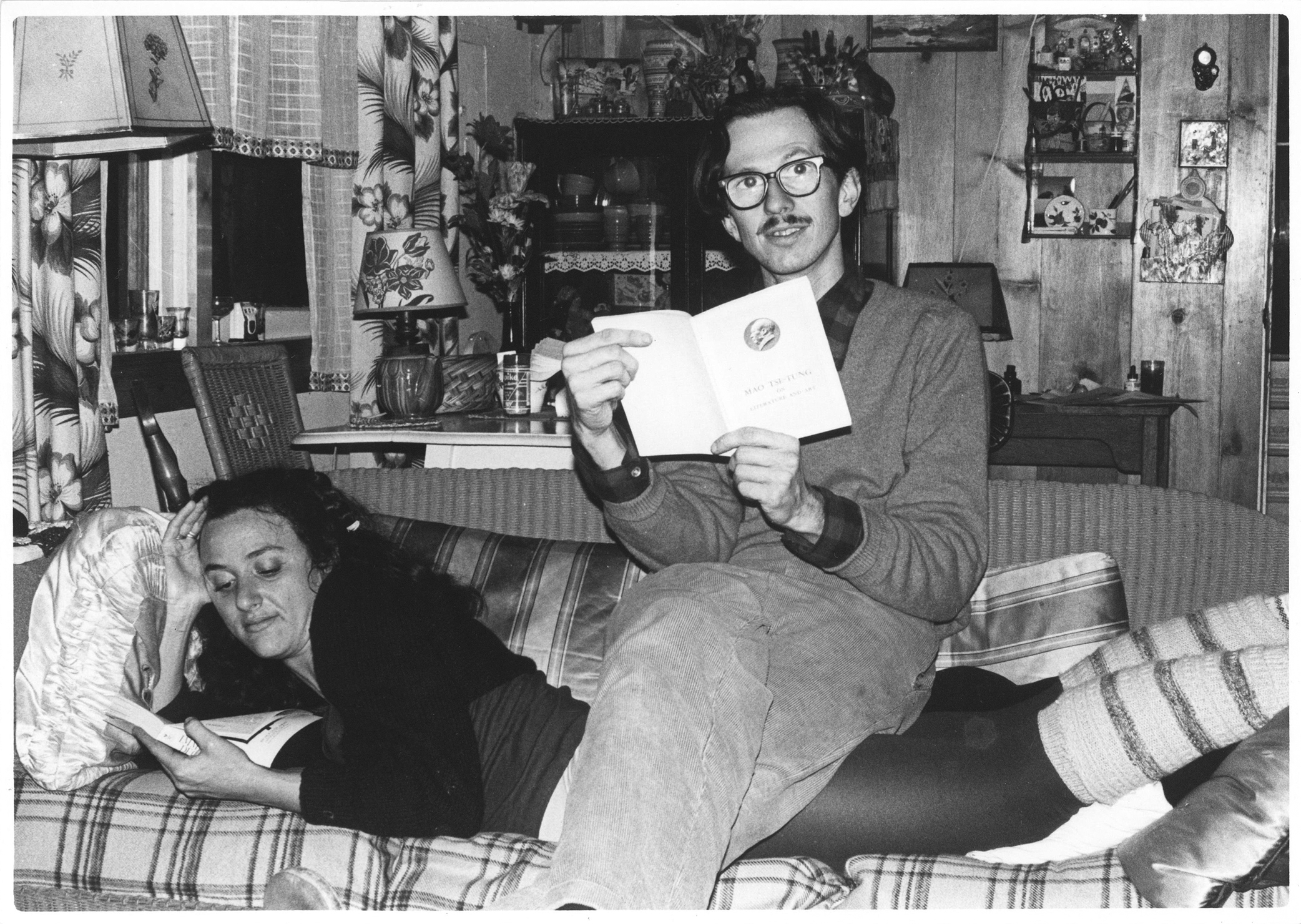

Robert Crumb and Aline Kominsky-Crumb at home in Winters, California, 1979. Photograph by Carol Engberg.

NADEL: The drugs stopped by 1973. Mainly weed and a bunch of acid. But by the late ’70s, he regained stability.

FREEMAN: I wonder if seeing his brother unravel from acid played a role, or if it was just the chaos his life had taken on. He and Aline refused to be casualties. His talent was the thing he was most attentive to, besides sex and records. He wouldn’t risk destroying his brain.

FREEMAN: It’s interesting that in trying to escape the chaos of his upbringing, he accidentally created an even more extreme version of it. But then he managed to rein it in, which is remarkable.

NADEL: He was always running, always trying to escape.

FREEMAN: Which he did, but he always came back. He must have been quite the charmer too.

NADEL: Unbelievably charming. If you look at pictures from the late ’60s, he was handsome.

FREEMAN: Yeah, he was cute. So committed to his nerd style though, which I respect.

NADEL: But still, a cute, successful cartoonist who wasn’t strung out.

FREEMAN: He might have even been hung. No wonder he wanted to put himself on the cover with his giant dong. You don’t mention that in the book.

NADEL: Someone I interviewed insisted I ask Crumb about it, but I didn’t.

FREEMAN: Although he does maintain an admitted hatred of women.

NADEL: He maintains a hatred of humans, period. And women for sure, but he also loves women.

FREEMAN: He’s like, “I love women. I have pages full of women. I have binders full of women.”

NADEL: I wouldn’t call him a feminist. He maintains this love-hate thing. And certainly, with Aline, that marriage would not have lasted if he hadn’t changed on a pretty fundamental level.

FREEMAN: Did he end up committing to her?

NADEL: No. They maintained an open relationship until she passed away.

FREEMAN: Holy shit.

NADEL: Aline had a long-term boyfriend until she passed.

FREEMAN: Well, it’s been great talking to you.

NADEL: Let’s hope we’re not canceled for this.