Mixing Metaphors

When asked where she lives, Danish mixed-media artist Nina Beier laughs. “That’s the hardest question you could ask!” she says. Prior to residing in New York, Beier lived in Berlin for five years, and before that in London, Paris, and Denmark, and in Mozambique as a child. This fall, she’ll complete a residency in Vienna, but until then, she plans to travel throughout Europe with her partner, artist Simon Dybbroe Møller, for their several exhibitions. “From the beginning I’ve never really stayed put anywhere,” Beier continues. “I think that does inform my way of thinking, and I see it popping up in work.”

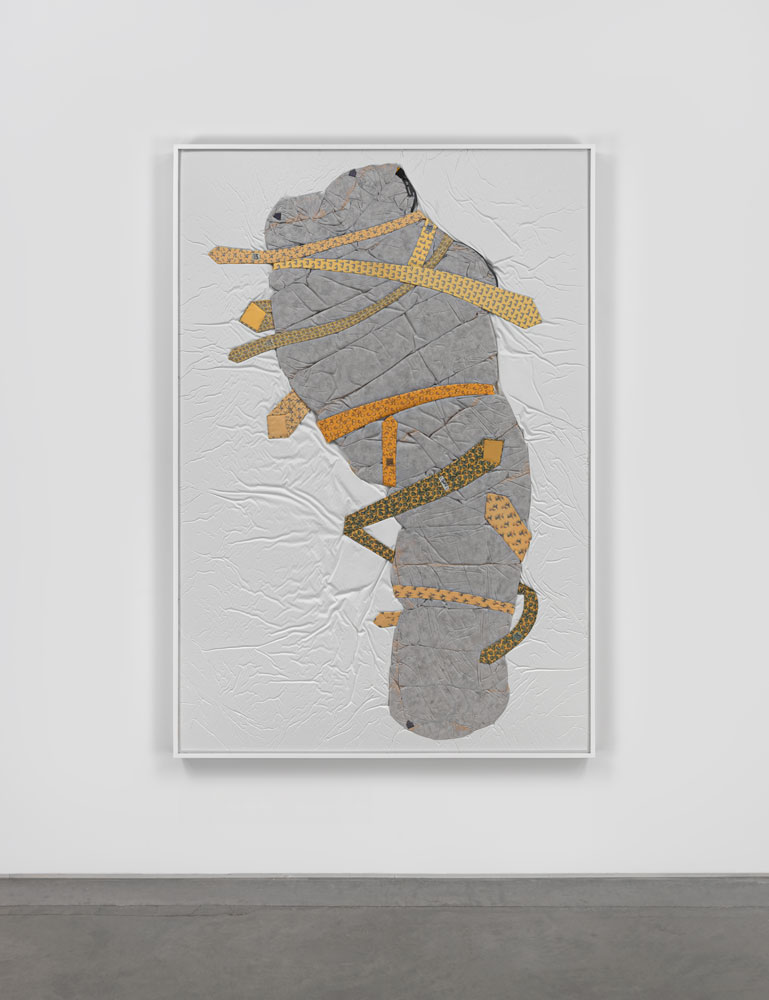

Last night marked the opening of Beier’s first New York solo show, which will be on view at Metro Pictures in Chelsea through May 23. Throughout the gallery, framed works with compressed down jackets, human hair wigs, and patterned Hermès ties fill the walls. These works evince the artist’s sense of the world as an increasingly commingled and overlapping place. “I became interested in what happens when everything is flattened, where everything has the same value,” Beier explains. “The [Hermès] patterns don’t have a foreground or a background…so even if they depict a mountain it’s the same size and on the same plane as everything else… I found it a really strong way of visualizing today’s reality.”

Metaphors act as one way to understand contemporary reality—or at least try to. In the sculpture series “Plunge,” Beier considers a subgenre of stock images that utilize metaphors. Oversized wine glasses and glass mannequin heads are filled with “water” (clear resin). Suspended inside are objects taken from stock images: schools of fish frozen mid-swim, a crab tangled in blue USB cables. In online image banks, like Getty Images, these objects lend themselves to a myriad of metaphors—they stand for something, but without any predetermined meaning, the metaphor remains open to varying interpretations. In 3-D fabrications, the once-stock images transform to the literal. We see the objects for what they are, and the result is slightly absurd and otherworldly.

“I somehow managed to create one big confusion of all these different trajectories going through the same field,” Beier says of her Metro Pictures show.

HILARY REID: How has living in many different cities influenced the work in your Metro Pictures show?

NINA BEIER: I’ve been using Hermès ties in the framed works because I was interested in this vocabulary they have—I was attracted to how it created this perfect narrative around an Imperialist worldview, or Eurocentric world view, where you just collect from the planet. These [tie] patterns can be anything from peanuts to a person picking rice in a field or Russian matryoshka dolls—anything from nature to culture to people, as long as they stay stereotypes. It is a wunderkammer approach to the world, where you can just bring everything into the same format or cabinet…. If you start looking at them there’s this kind of clear logic of cause that has to do with what we perceive as value. It’s interesting as a kind of catalog of human value. [Hermès] is a company that relies on appealing to their customers and depicting a sense of luxury.

REID: Can you tell me a bit about the “Plunge” series? What are the objects inside of the glasses?

BEIER: This language has been developed inside of image banks. I found that there is all of the classic image bank imagery, with beautiful people in office chairs laughing—

REID: “Woman eating salad.”

BEIER: [laughs] Yeah, there is that whole world, and I’m not very interested in that. But, I found that there is this certain trend within it that works with metaphor. If you are a [stock image] photographer, you only get paid when someone uses your picture, so you have to create images that are as open-ended as possible. I found all of these images that would [signify] anything from hope to despair, made with readily available small objects that are easy to photograph, often [depicting] some collision of two things where a little disaster would appear. A breaking arm or hammer—this kind of super simplified metaphor, but with quite cheap or loaded objects.

I think the idea of symbolic object is expanding, now including mobile phones and cables, as well as all of the accepted symbols. The fact that the photographers only get paid if their picture is used means that they have to think about what people will want to say in the future. There is no system in control that would survey this process, so they’re working very freely. I guess it’s the most intuitive image production today because it’s authorless. There’s no meaning attached to the image, there’s no intention, there’s nothing. It’s just the purest image, and then it will be loaded with all of these other [meanings] if it gets used. Most of them will never get used, so they are just creating this catalog of possible combinations of symbols. I wanted to bring those images back to their three dimensional origins—a place where we can look at them again, not as images, but as these actual symbolic meetings of objects.

REID: In a 2010, you wrote a piece for ArtForum about your solo show that was opening at Laura Bartlett gallery in London. You quote Alfred Korzybski, who said, “The map is not the territory,” meaning that the actual thing and its representation are not the same. You respond by writing, “But there is a lot to be said for confusion.” Can you talk about the idea of confusion and if it’s in this new show?

BEIER: That has actually been the easiest way for me to explain a certain group of objects I’ve been working with, as “confused objects.” Maybe it’s just me who’s confused. [laughs] For example, a real-hair wig is both an image of hair and real hair at the same time. The thing with wigs, of course, is that they’re frozen in one hairstyle and they’ll never grow. They really have that thing of being a still image, somehow, but the fact that it’s real hair at the same time is such a confusing thing, because it means that the wig is what it depicts. It really sits in both camps.

REID: Is the Metro Pictures show influenced by any specific works of literature or philosophy?

BEIER: No, I wouldn’t say that any of my reading has influenced it directly. When I’m doing a show, everything I read feels relevant, and I get completely confused because when I read it after the show it’s not about that at all! I make everything be relevant because I need to think about this one thing—I’m sure if I say anything now then next week, when the show is up, I’ll say “How is that [relevant]?” [laughs] I’ll just reveal that it’s impossible for me to think about anything else but my project.

REID: A professor of mine once said that if you’re working on a creative project and there are two ideas in your head that seem related, but you don’t know exactly why, you just have to trust that there is an undercurrent in your brain connecting them. The connection is not explicit, but the big mix of ideas eventually becomes the artwork.

BEIER: I really trust this, but the thing is, we always are able to make things make sense because we need to get somewhere.

REID: That seems good and bad.

BEIER: [laughs] Exactly.

REID: Have any elements of your performance pieces translated into your sculptural works?

BEIER: I never really thought of them as performance—when I’ve made performative works it’s always been because something had to be live in some way, mostly because I couldn’t find a way to make it not. [laughs] For example, my piece with a dog playing dead on a carpet [Tragedy, 2011] that showed at Metro Pictures a couple summers ago is exactly about that space between living and the dead. There is this moment when the dog is asked to play dead, where it goes from being active and then it just whoosh! [makes falling over gesture]. Everything goes quiet and the only thing that moves are its eyes. I was interested in how it became sculptural, or image, or whatever term makes more sense, for that moment of the agreement of the performance.

“Play dead” is the third [command] you teach dogs: it’s “sit down,” “lie down,” “play dead.” It’s the most loaded one, the absurdity of us looking at animals and being envious that they’re not aware of their own death. As a solution, we come up with forcing the animal to play out its own death unknowingly—it’s such a brutal tradition, but at the same time there’s quite a beautiful contract between these two beings. It is the human’s need to deal with this image, and then asking the animal to perform it for us so that we can get in touch with these feelings. Then when the dog is done, it just stands up and the moment is so quickly gone. I think, in a way, it does talk about sculpture, and the permanence of sculpture, and the fact that we do sculpture in bronze or because we want them to outlive us; we want them to be immortal, that’s kind of the drive behind making objects, if you go to the root of it. Somehow, [with] this dog moment, I feel like I’m saying three things at the same time. The relationship between death and image is the key, a bit like the hair that doesn’t grow anymore.

REID: Can you tell me about the coco de mer you’ve included in this show?

BEIER: I found the coco and realized, “Here is a nature-made nude.” Nature made a sculpture of a nude human—how can this object exist? And, of course, nature did that, and it was punished by humans, because we took them back! The way that they’re being dealt now, you can only buy the antique ones that are not fertile because they are regulated. We have collected these and brought them home. I guess it goes back to the confused object—their image is so much stronger than their reality, so that it’s sacrificing itself to become [an] image.

REID: And now they’re in a gallery in New York.

BEIER: [laughs] The way that they’re listed on eBay, or wherever you can buy them, is usually sculpture. The fact that we can only identify this object because it’s so sculptural is really interesting. So that’s where all these things meet—the handmade carpet, the human-grown hair, the naturally made female nude, feathers for synthetic coats. I somehow managed to create one big confusion of all these different trajectories going through the same field, but through all of these different directions.

“NINA BEIER” IS ON VIEW AT METRO PICTURES THROUGH MAY 23.