New Again: Zaha Hadid

Iraqi-born British architect Zaha Hadid passed away at age 65 following a heart attack in Miami last week, but her legacy will live on as a fixture within the history of modern art and architecture. Exemplified through her numerous buildings around the world, Hadid was known for forms with multiple perspective points, fragmented geometry, and wildly futuristic shapes that often seem to defy gravity. Her buildings act as much more than functional structures; they are pieces of art. In 2008, Patrik Schumacher named her style “parametricism” and it has since become an important movement in avant-garde architecture.

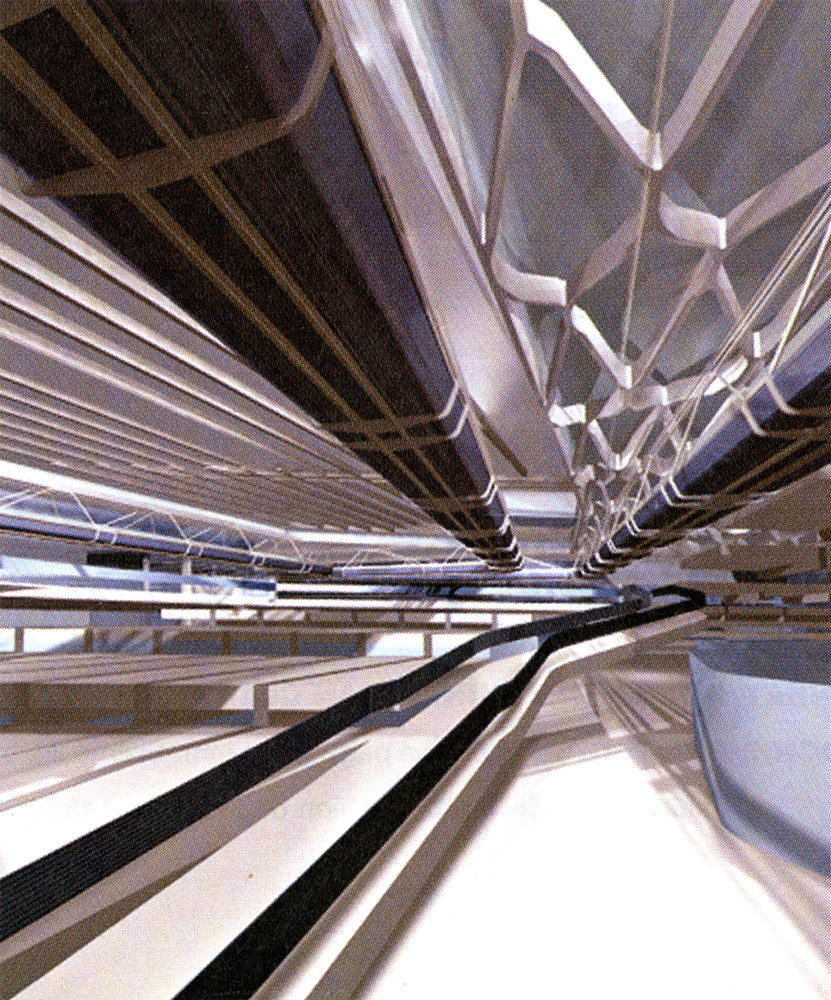

Hadid’s most iconic works include the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, Vienna University of Economics and Business’s library, and the London Aquatics Centre, which was originally built for the 2012 Summer Olympics. Each of these works employ her favorite material, concrete, and stand out amongst their surroundings in a way that makes them seem otherworldly. Before her passing, she designed a stadium that is currently under construction and will be used for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar. And more than just architecture, Hadid also created incredibly intricate and geometric jewelry for the likes of Georg Jensen and Caspita, and collaborated with brands like Adidas.

In 2005, Hadid sat down with fellow architect Rem Koolhaas shortly after becoming the first woman, and the first Muslim, to win the Pritzker Architecture Prize, considered by many to be the “Nobel Prize of architecture.” The two legendary designers discussed Hadid’s perspective at the midpoint of her career, what she learned from a younger generation, and her role as a Muslim woman in an increasingly Islamaphobic world. —Wil Barlow

Zaha Hadid

By Rem Koolhaas

How do you answer critics who call you a diva? If you’re architect Zaha Hadid, by creating buildings that cannot be ignored. Here, she speaks with fellow rafter raiser and every young architect’s hero, Rem Koolhaas.

The past few years have been big ones in the career of Zaha Hadid. Last March she was awarded the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize, marking the first time a woman had been so honored. And in May 2003 her Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art was opened in Cincinnati to immediate and wide acclaim (at least bringing one of her visionary structures to American shores). These successes are especially poignant because for a while it looked as through Hadid was destined to be remembered more for the great buildings she never built than for the ones she did. Though indisputably one of the world’s preeminent architects, at 54, this Baghdad-born Londoner has a relatively small body of completed structures to her name—a fact purported to have as much to do with her abstract presentations as to her disinclination for compromise. Has all that changed? Maybe, but with a tidy list of commissions underway and a comprehensive four-volume monograph of her work released last November by Rizzoli, one thing’s for certain: The world won’t have to wait long to be treated to more of Hadid’s powerful imagination. Here, fellow architecture luminary Rem Koolhaas speaks with his friend and one-time colleague.

REM KOOLHAAS: Where do you feel you are in your overall career—the middle, before the middle, beyond the middle?

ZAHA HADID: Hmm, in terms of achieving certain ambitions, I’d say it’s beyond the middle—as you know, these kinds of goals keep getting shifted all the time. If I had a certain ambition 10 years ago, 20 years ago, it’s not necessarily the same now as it was then.

KOOLHAAS: You were recently awarded the Pritzker Prize, which made me wonder about your attitude toward honors. Does receiving them give you satisfaction, does it make you nervous, does it increase your burdens, does it stimulate you?

HADID: It’s too early to tell with the Pritzker. It’s not a burden so far. It has made people view me more as someone who can do a project, but it took me so long to be accepted. But at the same time, work has not been flooding through my doors because of it. I don’t really know that it has such long-term affects.

KOOLHAAS: Does it bother you that from now on you will be described as “a Pritzker Prize winner”?

HADID: I’m not sure how long this will last. I mean, you would know better. [Koolhaas won the Pritzker in 2000.]

KOOLHAAS: In my case it is now the inevitable adjective [both laugh], which, I must say, really bothers me.

HADID: I’ve never really been into all these honors because it implies you’re kind of a careerist. One should take it in stride. My concern is not taking it too seriously and becoming pompous. That bothers me, and I try my best to just enjoy it and carry on. As you well know, no matter how many prizes you get, you are still walked all over by your clients. It’s a very tough profession, and so it brings you down to earth. You don’t have the time to think “Oh, it’s great. I’m fabulous.”

KOOLHAAS: Do you think that your work is consistent, or do you think you’ve changed?

HADID: I think the work has changed. When I first started doing what I was doing, it was new, but it’s very difficult to be new all the time. There’s a point when you have to try to always be inventive—out of that you do discover things that you would never have thought possible. On the other hand, you have to build on your repertoire and it make it fresh in different ways. You kind of have to juggle between these ideas of new. One thing that has remained consistent in my work is the connection between project and site. I think the customization of site becomes very interesting, though the way you deal with that in each case is quite different.

KOOLHAAS: Would you say that’s the most consistent, underlying ambition in your work?

HADID: Well, that and the study of ideas relating to civic space—though interpreted differently in each case. How you interpret the combination of demands makes the situation quite unexpected.

KOOLHAAS: In terms of what’s new in architecture, do you feel like the younger generations are breathing down your neck?

HADID: In what way?

KOOLHAAS: Has there been anything in the work of your architects or colleagues that is particularly fresh and that has made you think twice about what you’re doing?

HADID: Not yet. [laughs] In a way, everything has become quite predictable. There have been new interpretations in younger architects’ work, but I think it’s not so surprising. I’m still waiting for the moment when something triggers me.

KOOLHAAS: And gets you nervous.

HADID: But I’m, by nature, quite nervous about that. One thing you learn when you’re on your own early is to be self-critical, which has kept us on the edge. I’m not saying we are always doing great work, but we are always pushing.

KOOLHAAS: How much do you teach?

HADID: Well this year I was teaching at Yale and at [the University of Applied Arts] Vienna.

KOOLHAAS: How often are you in the classroom?

HADID: In Vienna I go once a month or so.

KOOLHAAS: Is teaching important to you?

HADID: I don’t have the same intensity of teaching as I did 20 years ago. I had a very different method then: I was very hands-on and was there all the time. But I still think you can discover things through teaching that you might now know about otherwise.

KOOLHAAS: So through teaching you learn yourself, particularly about certain techniques?

HADID: Yeah. Last year, for example, it was about housing in England, and the year before that it was about the World Trade Center. In terms of mass interpretations, it was very interesting and refreshing, actually. It was a very large-scale project, and none of my students really went for these kinds of spindly towers.

KOOLHAAS: It was interesting to you because it made you enter zones that professionally you haven’t been able to deal with?

HADID: Well, depending on the topic, it makes you go with more depth into a project that you might not know that well.

KOOLHAAS: How do you resolve that contradiction between having an incredibly strong personal language on the one hand and an enormous number of architects working for you on the other. How many people are in your office?

HADID: About 65 or 70. But it’s not just me who has a strong hand—quite a few of us here deal with the team. Also, many of the people who are now leading projects in my office started here years ago; they trained here. There is a tremendous degree of freedom in the way they lead projects, but there is an understanding that the larger the office becomes, the more difficult it is to have that freedom. It’s not necessarily more critical to do every project differently, but to let other people have a voice.

KOOLHAAS: Is that happening?

HADID: Yeah, I think it is. It’s still kind of in the same morphology, but now that the projects are becoming more diverse, it makes it more interesting and puts more pressure on people.

KOOLHAAS: So would you say that this is an aspect of the second half of your career?

HADID: Yes. It’s more important to me now that we do a project well as opposed to one that should be seen in a particular way. People assume that there is a hand that governs everything, but I think it’s better to try different processes and to discover new things. As the office gets bigger, there is more demand on your time and work, so you begin to see differently. And I think the experience one gets from building things also has an impact on the way you do things.

KOOLHAAS: Can you say something about concrete? Because when I look at your work I have a feeling that you love it more than any other material.

HADID: It’s a fantastic material, and there is so much you can do with it. Concrete shows up in some of my early projects very well—for example, Vitra [the Vitra Fire Station in Weil am Rhein, Germany] or Strasbourg [Terminus Multimodal Hoenhem Nord in Strasbourg, France]—as well as the current project in Wolfsburg [the Phaeno Science Center in Wolfsburg, Germany]. I love concrete, but I think we should also look at other things. For instance, there is a preoccupation in my work about what structure can do and how you should be true to the material. Now we can begin to look at taller buildings that are more complicated. Maybe the structure is concrete, but we can begin to look at the skin and how you can interpret that. I don’t think it should just be concrete architecture.

KOOLHAAS: So that’s another part of the second half of your career.

HADID: Yeah, nothing is achieved completely.

KOOLHAAS: I have a series of words that I would like you to react to very briefly. Here’s the first one: Iraq.

HADID: Tough one. Iraq is very painful for me.

KOOLHAAS: England.

HADID: Tougher one. Funny enough, the Arab world and Britain have something in common, and it’s why a lot of Arabs come and live here. Unlike America and Germany and a lot of other places where it’s black and white, there’s a similarity in the “maybe” of the Arab world and England, and therefore a constant postponement to solving the problem. On one hand it’s a tremendous freedom, and on the other it means they don’t care. Here in England it’s a gray world, not only because of the weather.

KOOLHAAS: China.

HADID: Very exciting, a new world.

KOOLHAAS: Islam.

HADID: It’s very misunderstood. I don’t approve of any of the recent religious branching—it’s not easily resolved, but I think because of Western imperialism they react in an exaggerated way. For example, some people who were very liberal before are now wearing veils, and the people who were strict are more modernized. There is a basic misunderstanding between the West and the Islamic world that if the try to understand the problems it will provide the cure.

KOOLHAAS: Do you think you could provide a role there?

HADID: Nobody has approached me. Of course, I would like to play a role, but I think there are people who understand it better than I do—plus I look at it from the outside because I was brought up in the Islamic way. It baffles me why it is so misunderstood. I think that all these things are reactions not about religion, but about culture and politics.

KOOLHAAS: This one I’m not sure of myself, but what about the role of women?

HADID: People ask me this question all the time. I really don’t know. There is a difference between men and women in Islam, but for work I’m not sure if it manifests itself. One of the liberating situations in my life was that there was no stereotype, and I didn’t really care what people thought and how I should dress and how I should behave. That really gave me a degree of freedom. I was kind of freaky, so it worked in both ways. In terms of whether the male and female brains operate differently, I’m sure they do, but I couldn’t say how. It depends on the degree of confidence your school or your parents gave you, and whether you’re male or female has tremendous impact on that. I think this affects women a lot in your careers—if you try different things it gives you possibilities to make it to the next step. Many women don’t have the encouragement and support they need to do that. It’s not about the way they think or their brain being different or whatever.

KOOLHAAS: I have one final question: Have you ever imagined yourself with some other profession?

HADID: Many years ago I wanted to become a singer. I also think I could have gone into politics or become a shrink. These are the things I think I was sent to do.

KOOLHAAS: So, politician, shrink, and singer?

HADID: All combined. [laughs] Sounds like a candidate for the presidency. When you’re much younger you think you can do anything. I’ve always loved architecture, though. I’m not sure if I’m going to have a career change now.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE FEBRUARY 2005 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.