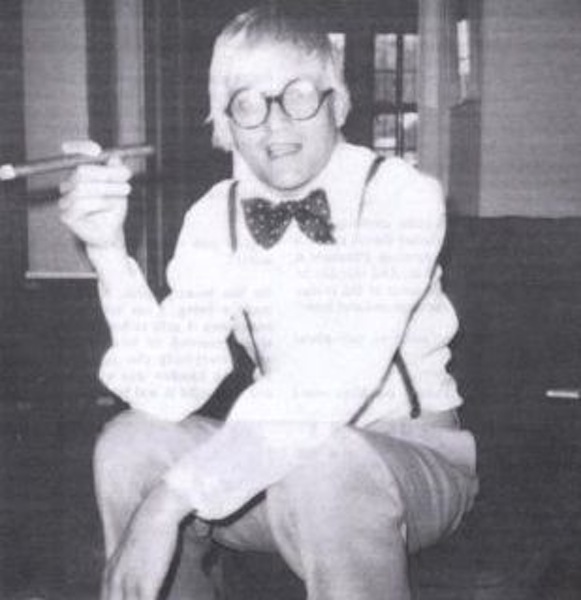

New Again: David Hockney

In New Again, we highlight a piece from Interview’s past that resonates with the present.

This November, the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art (LACMA) will honor filmmaker Martin Scorsese and British artist David Hockney with their third annual Art + Film Gala. We’ve spoken with Hockney many times over the past few decades. In the interview below, reprinted from our July 1973 issue, Hockney cheerfully discusses his complicated relationship with the US, how to translate the weather into art, and his views on the latest Academy Awards. We can only hope that he’ll be as frank and animated in his acceptance speech.

The Annual David Hockney Interview: Tea in Hollywood

By Valerie Wade

Last July Interview talked to all-star British artist David Hockney about art. This July Interview talks to David Hockney, over breakfast at Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont, about America. Notes for the casual reader: Ossie Clark is a longtime friend and one of England’s star fashion designers. Celia is Celia Birtwell, Clark’s wife and star fabric designer.

DAVID HOCKNEY: The trouble with America is that you cannot pay more than one dollar for a cigar.

VALERIE WADE: Is it any good? That cigar?

HOCKNEY: No, they are terrible.

WADE: It looks quite impressive.

HOCKNEY: They are awful, but what else is there? Every time someone came from England, I had them bring a bunch of Cuban cigars, but they’ve all gone now. You can buy anything else—heroin, cocaine—on the corner, but you can’t buy a Cuban cigar. It’s ridiculous.

WADE: Is that why you don’t want to live here?

HOCKNEY: Well, you know I used to live here. I lived here for about four years. I mean, I kept leaving, I kept going back to England. From 1964 to 1698, most the time I was living here.

WADE: Maybe you’ve grown up?

HOCKNEY: No, it’s not just that. I thought that and that’s why I never told anybody. I thought, yeah, it’s less sexy and it must be me growing up. I never mentioned it to anybody at all, but this time in January, I met a boy here. He was about 22 and he asked me just like that, did I think America was as sexy as it used to be? I thought for a minute, and I always think the secret of staying young is to have a bad memory, you know… Never remember more than two years back and so then I thought I’d be honest, and I said, “Well, to be honest, no, it’s not.” And he said, “Oh, I’m so glad you said that.” He thinks it is not. You see. But he was only 22. And I asked him to elaborate and then I said, “Oh well, I’ll tell you now because I thought it was me just getting old and I should never mention it to anyone.” Mind you, I think it’s getting better, I think it’s coming back a bit now.

WADE: Since when?

HOCKNEY: Year, or six months even. But the bottom was about… when was I here? 1970 or 71. Everybody looked like Jed Clampett. Oh, I hated it. In 1971 I went to San Francisco. I was going to Japan. We arrived in San Francisco, I rushed to this bar, called The Stod or something, and everybody looked like Allen Ginsberg in it. Oh, I was expecting nude go-go boys on the counter and everything kind of red lights and sexy and everything. Oh, it was awful. And I just thought, Well what am I gonna do? What am I gonna say? I won’t say anything. But I don’t know why it was [that] everything just didn’t look as sexy. I mean you can go in bars now and see people screaming on the floor or on the counter.

WADE: Here? I haven’t seen them.

HOCKNEY: Yeah. They have nude go-go boys. No, I think they are closing ’em down now. I think. I don’t know why…

WADE: Are they good looking, the nude go-go boys?

HOCKNEY: Quite good. I took Bianca Jagger to one in the Valley to see these nude go-go boys. They weren’t bad. One or two were really cute, and then the rest weren’t that good. But in 1964 they used to look fantastic. I mean, there was a very Californian look, quite distinctive. Nobody looked like that anywhere else. It was marvelous. It’s a warm climate. People don’t wear that many clothes.

WADE: They don’t get fat.

HOCKNEY: And because you don’t wear that many clothes, you look after your body a bit more if you are on the beach. Then it kind of changed a bit. I can’t figure it out. I don’t know if it was the Vietnam War or guilt or what. Well, you must have noticed, at one time in America, everybody looked like they had just come back from Vietnam in their old clothes, and they really got to look awful. Everything seemed to disappear for me, and in 1968-69 I went back to live in England. I decided I wouldn’t live in America. I got fed up of it.

WADE: Because it visually deteriorated?

HOCKNEY: Yeah, well then it got a bit boring. Things get you down that everywhere is the same. Unless you go in a very expensive restaurant, you know what the menu is gonna be. Always, you know what the food is gonna taste like, don’t you? You always know. I’ll tell you what you should do—here’s a trip you should take because it is incredible. Drive from New York to Buffalo. It’s 800 miles and every 30 miles there’s a stop. You know, a garage place and a restaurant. And they are all identical. Absolutely. Once you’ve stopped in one, you stop in the next one and you know where the bathroom is. You know where to park your car.

WADE: But that’s not new about America.

HOCKNEY: No, as a matter of fact, that was in 1965 that I did that. But it’s just that there are some pleasures you can’t have. I mean driving in France or Italy. I mean it’s a pleasure, isn’t it? Planning where you might stop. The only pleasant place to drive around here is in the West. In Arizona and Utah, that is fantastic. But actually I’ve decided it’s picking up again.

WADE: You mean Los Angeles or New York?

HOCKNEY: Yeah. Maybe all of it is picking up a bit. Do you think it was the drugs that did it all?

WADE: Do you mean made it better?

HOCKNEY: What? They made it worse!

WADE: Yeah, I think so. I don’t think people are taking so much now.

HOCKNEY: Yeah, I must admit I am bored by just meeting people, completely zooked out. It’s very boring. Here now, that doesn’t happen as much. I noticed that in the three months I’ve been here.

WADE: Do you think people are getting more done now, because of that?

HOCKNEY: I don’t… I must admit. There are lots of things I don’t understand. I mean, a few years ago, the revolution was always around the corner. Not that I ever thought it was. You would never have a revolution in America. A lot of people actually believed it, but I wasn’t sure exactly how. But it really just fizzled away completely. There is a very, very funny article, but it’s not meant to be funny. I read it yesterday in a magazine called Art in America, and the article was called the “Politicization of the Avant-Garde.” And it’s an account of the art workers coalition in New York and it’s quite marvelous reading. Because looking at it from a distance of, I suppose, three years—and I never came across it much—but reading about it, you simply see a great deal of what it was about. It’s simply a lot of people fighting for their place in the sun. It’s a perfectly natural thing to do and everything, but it was quite amazing. And I thought that the woman writing the piece realized you know looking back on it, it was a thing you could smile about—if not laugh at—and then suddenly the last paragraph—I’ve forgotten the way she put it—but it suddenly made me realize that she actually thinks that it was all very serious.

WADE: I must read it. But how do you feel about New York?

HOCKNEY: Well, I went to NY last year. I had a show there, so I went and I stayed a month. But when I first arrived I thought, “Oh my God. I’m just gonna stay a few days and go back. I couldn’t bear it.” But I finally finished up staying a month and the longer I stayed, the more I enjoyed it. Really. The one pity is that at night it’s not as nice. There are not as many people on the street any more, are there? It used to be so good.

WADE: Do you think it’s because people are frightened?

HOCKNEY: Well, I mean, I’m not that scared. But obviously a lot of people are. Otherwise they’d be out walking. I mean, when I first went there—I suppose about 1961—I thought I was fantastic. You know, at midnight there were still lots of people about, and it was terrific. I mean London then, in 1961, everyone was really tucked up in bed. Or everybody I knew. I don’t know. Maybe I should stay longer, Henry (Geldzeler)’s always saying why don’t you come and stay six months and work, you know.

WADE: I don’t know why you don’t.

HOCKNEY: Well, the truth is when I got back I’m thinking about going to Paris for three months. I mean I love Paris. And I don’t really speak French. I only know restaurant French and I thought I could improve that. But maybe next year. You see, the summer is a bad time to go to NY. It is awful then. And the summer in the Mediterranean is nice.

WADE: Are you missing England now?

HOCKNEY: I am a bit. But not that much because the truth is that it’s all gonna be a mess when I go back. I mean my friends. It’s all a mess with my friends. I don’t know. What with Ossie and Celia, and Peter, I, er, really kind of liked it here on my own for a bit. That’s why I thought I’d go to Paris just on my own. And when I came here at first, I tell you what I did, I thought, “I’m not gonna watch television this time. I’m fed up with television.” So I thought I’d just read. And I’ve done four times as much reading here in three months, as I would have done in London.

WADE: What have you read?

HOCKNEY: I read all the long Flaubert novels. Re-read every one of ’em here, which were terrific. I’d read most of them before. But I’d never read the last one he did. What else have I read? Turgenev. I read a few of his novels. And I read Delacroix’s journals, which I’d only ever read in bits before, which was fantastic. Normally, I read loads of trash all the time. Once you get into it you think, “Oh, it’s so much better than television.”

WADE: What was the work you were doing here?

HOCKNEY: Well, I came to do some lithographs, which I rarely do—I do mostly etchings. I did some in 1965, and I thought I’d do them on the weather ’cause I did one painting in London of some rain and I called it Japanese rain on canvas. And it was based on the way the Japanese paint rain, although I did try to be very literal when I was doing it. I put it on the floor and I put some water in a watering can and sprayed it on, you know, so the rain had actually fallen onto the canvas, although you can’t tell. It doesn’t make a difference. Only if you know about paint would you know. And so I thought I would do the weather. I came in January, and I started on it and I did the rain first. Then I did mist, and I did sun. Then I couldn’t figure out quite how to do everything. I went to Palm Springs and went up to the snow and finally did snow. Then I did a flash of lightning and I wanted to do wind. And wind was the most difficult. I could not think quite how to do it. I thought of palm trees bending over something like that, and I made lots of drawings. And suddenly I sat on the beach reading at Malibu, and the marker I had in the book blew away. And suddenly I realized that for the wind I’d do all the other prints blowing away across Melrose Avenue. And for the wind it’s just the other prints blowing about.

WADE: Did you do smog?

HOCKNEY: Well, I did a black version of the mist which looked a bit like smog but somebody said, “No, it looks like”—what’s that steel town called?—”Pittsburg.” They said it looks like Palm trees in Pittsburg and there aren’t any there really. I did a few other little things. I did a few portraits of Celia and a portrait of Ken Tyler, which I spent about three days drawing from life on a big stone, and he hated me playing Wagner opera so I gave him the title “The Master Printer of Los Angeles” because I read somewhere they said he was a master printer.

WADE: Did he like that?

HOCKNEY: He loved it. He loved posing for the portrait. He was so pleased about it that he really sat still and the stiller he sat, you know, the subject of the picture changed because instead of just drawing Ken, you are drawing him sitting still posing for his portrait, and there is a kind of eagerness in his body and his face it’s a bit like, well, he’s not quite like Cecil Beaton. I suppose Cecil is so warm really, he really sits still. I once did a drawing of him for Vogue. I had to do 20 drawings of him before we got one that I was satisfied with and he was. I was satisfied. Cecil thought he looked awful and “could you alter the mouth, a little bit there,” or the eye, so then I’d start again. I did nearly 20.

WADE: How long did it take?

HOCKNEY: Well, I went for about three weekends. But he really knows what he looks like. Some people don’t know what they look like really. But Cecil thinks he does, so you have to do it that way.

WADE: But does he know what he looks like, or what he wants to look like?

HOCKNEY: Well it’s probably what he wants to look like. But he knows which way he should look and he should wear a hat, he always had to have a hat. And I think hats are quite difficult to draw, so it was an extra problem. I haven’t seen him for a long time. Do you know him?

WADE: No. Have you read his diaries about Garbo?

HOCKNEY: His descriptions of the woman he loves are hysterical. According to him she is “forever fertilizing the lawn and smoking Old Golds.” He would notice glamorous things like “the lump on her nose was cartilage and not bone,” and that “her ankles and legs looked somewhat scrawny like certain poor, older people’s.” Once they were having dinner—Beaton “longed to dance with her” and thought that “her woolen clothes would put the other woman’s gaudy glad rags to shame,” but that he just had to admit that “her galoshes over large boots would have looked curious on the polished floor.”

WADE: Do you like him?

HOCKNEY: Well, yes. I do. He’s quite amusing really isn’t he? I’d read his other diaries and in a way they are more interesting. I thought it was a bit boring all that. And one day he noticed that the little lump at the bridge of her nose was of cartilage and not bone!

WADE: What else do you want to say about America?

HOCKNEY: I’ll tell you what I might do. Next year I might try six months in New York. I mean a lot of people I know really love it. Mark Lancaster went to NY last year, I think, just to visit and he’s decided he’s gonna stay. I wonder what the secret is about New York. I should find out.

WADE: I think the secret is going for one month and staying for six months.

HOCKNEY: Yeah, that’s what happened when I came here. The very first time I came to California I came with the intention of staying a year and I did. And then I went back but then I found myself coming back after two months in England. Then the following year I came back thinking, “Oh I’ll go back to California for two months.” And I stayed another year. In fact I only left Los Angeles once. In London, you know, I leave all the time. I think it’s incredible if I stay a month if I’ve not gone anywhere. And I never go to places in England really, I go to Bradford because of my parents and other than that I just got to London airport.

WADE: Yeah, you once said that your favorite road in England was the one to the airport.

HOCKNEY: Well, that was when I was really off England. I mean I go up and down about England really. Sometimes I think it gets really tedious and boring.

WADE: Do you think it depends on your emotional life?

HOCKNEY: I suppose it does a bit. I don’t know, then sometimes I think the art world in London gets really boring. I mean it’s really blown up out of all proportion to what it really should be and somehow you don’t feel that here, because there isn’t one. I mean, you never come to California for the art world, there is one but it’s…

WADE: But do you come to England for the art world?

HOCKNEY: No, but being English, and that’s how I made a living. I am involved in it, but sometimes it gets rather tedious. I really always wanted to leave. I left London when everybody else said it was good. Swinging London was, what, 1965 and ’66, and I thought it was boring then, really a drag. There are a lot of things I still think are a bit bad about it. But then, one of my complaints about it was that it’s always just a bit exclusive, or you need too much money. Like, for nightlife in London—although it is a lot better now, I mean all those kind of exclusive “swinging” clubs. Anyway, swinging London was too straight for me. It wasn’t really gay at all was it? I suppose that’s the truth, that’s why I didn’t like it.

WADE: It was about six straight people photographing six straight people.

HOCKNEY: Yeah, well you see there are six straight people that live here. I think they live over in North Hollywood.

WADE: Can you name them?

HOCKNEY: Somebody met them once… You see I really used to think this was an incredible gay city. It is really.

WADE: Do you think it’s more gay than New York, or is it just that people don’t wear so many clothes?

HOCKNEY: Yeah, it’s just they don’t wear so many… I mean there are more beautiful boys here.

WADE: Did you see the Academy Awards?

HOCKNEY: Well, I only watched it because somebody told me that 80 million people were gonna watch it, so I thought well, I might as well see what they are all looking at. But I did like reading later on that the girl that Marlon Brando sent was Miss Vampire. I must admit that I thought it was a bit dumb of Marlon Brando. I think he didn’t really know what he was saying or doing. I mean, if for instance, he said that Hollywood had really not done that Indian justice and they were terrible to Indians. The truth is any intelligent person always knew that. I always knew that those films, what they did do was reflect, as all art does, the bigotry, or the passions of the people who made them. And he suggested that they should not be shown on television didn’t he? He’s suggesting there be censorship. Well, there’s a case for censorship. I mean, I know there are good cases for censorship, but normally in America people don’t take any notice of ’em. And I think it was as thought he did not understand art. It was as though he did not understand what art is really about. What he did was dig up without mentioning it, and probably not understanding it, he dug up old 19th century arguments about art and morality. There were always arguments then about art and morality. And I mean, I know they should still be going on, but if you are gonna dig them up or deal with them that’s what you should talk about. And then all that thing on the news, he’s on his way to Wounded Knee, he must have been going on a horse because I was waiting for him to get there and he never got there. It was a bit funny I must say… I understood his compassion. It’s admirable but somehow there was something as empty about it as the rest of the show really.

WADE: Do you think he should have done it himself?

HOCKNEY: Well, yes, certainly he should have done it himself. And I think it is his duty to think about it a bit deeper than he did. I think if you are going to do things like that, I think you have the duty to think about the implications, about what you are really saying and everything. And it was too shabby. It was as though he was rather lazy in his thinking and I think that’s a little unforgivable. Obviously, some people can think better than others. But would assume that Marlon Brando is quite an intelligent man. I suppose he did it for publicity for the Indians, didn’t he?

WADE: Yes. That’s why it was such a pity to use an actress.

HOCKNEY: Specially someone who’d been Miss Vampire only two days before. And then on television afterwards they showed a guy, an Indian who’d been in lots and lots of movies who said, well, he realized the movies were terrible and he was not going to make them anymore and this that and the other. But what was the truth, he did it for the money. I mean, he has to live like everybody else. I mean, there is a certain dishonesty. He must know what he was about. He could say, well, I was trapped by it, but I had to make a living like everybody else. At least you would get it a bit clearer.

WADE: Have you met many movie stars here this time?

HOCKNEY: Joel Grey I met. Well, I met him in London. He was living about four houses from us in Malibu.

WADE: Were you near the Colony?

HOCKNEY: We were in the Colony. In the penal Colony, I couldn’t bear the drive. That’s what did me. Twenty-five miles into Hollywood. And I’d come in in the morning. And I’d go back in the evening, pick up Celia, come back here. I was driving over 100 miles a day, and going nowhere.

WADE: Did you meet anyone else in the Colony?

HOCKNEY: Well, Lee Marvin came by one night. Just to knock on the door. He used to live in that house and he was looking for somebody else. Who else? Not many. I meet more movie stars in London than I do here. Mick Jagger was here, I met Mick when he was here.

WADE: You need to come to Los Angeles to meet Mick?

HOCKNEY: And then Bianca came.

WADE: Do you prefer her with short hair?

HOCKNEY: She looks pretty good with it. A few people are cutting their hair. Ossie cut all his off. Well, he looks a lot younger. I mean, I can’t have long hair because it falls. I bleach it too much. I just see it fall off. It does not fall out. My hair is really strong and tough.

WADE: How often do you bleach it?

HOCKNEY: Well I touch it up, maybe once a month.

WADE: What with?

HOCKNEY: With Lady Clairol. What’s it called? Ultra Blue Lightener with boosters, or something.

WADE: Do you ever go to Philip Kingsley [a trichologist in London]?

HOCKNEY: Well, I went there once. I thought that was all a bit too indulgent. I mean I haven’t got bad hair. Ossie took me along once, he said come along you’ll feel really good and I go in his office and he’s got all the books ever written about hair at the back of him, all three of ’em, on the shelf. And he says I take a sample of your hair and tell you what’s wrong with it. So I said I know what’s wrong with it, it’s just dry from being bleached, and he takes it, and its all sort of pseudo-scientific, and he put a load of gunge on it, and it was not better than the stuff I put on I could do it myself just as good. I know how to look after it. It doesn’t look too bad, does it? I’ve been a blond for 12 years. I’ve been a blond so long, my mother thinks I was a blond naturally. The first time what did she say?… My father walked straight past me, mind you I was wearing dark glasses. It was a Kings Cross station, London.

WADE: Was it the same color, white?

HOCKNEY: Yeah, I’d just come back from America and they suddenly said they were coming to London, my brother was going to Australia, and my father walked straight past me, and I just said, “Oh, it was some strong soap I’d used.” I didn’t say I’d bleached it, really then. And my sister-in-law thought it looked terrific, and at first I was not gonna keep it like that but I did. I think it suits me.

WADE: Have you been to many shows or movies here?

HOCKNEY: Quite a few movies. Not that many. You know what I have not been to and I’m slightly shocked by it. I have not been to see any of those gay movies or Deep Throat or… I don’t think I could take Deep Throat. I don’t like that heterosexual stuff, it makes me a bit, oh…

WADE: Don’t bother with Deep Throat.

HOCKNEY: They are boring because they don’t realize that you should build up to it. I mean just watching somebody screwing somebody else gets boring; after five minutes, you don’t want to see it anymore. The exciting thing is the buildup. I mean, we went to see Elvis in Las Vegas. But again the most exciting moment was the last 15 seconds before he appeared on the stage ’cause I’d never seen him before. Mind you it was a rotten evening. You see, this is America I said to Celia, I’ve got these tickets for Elvis in Las Vegas so we’ll go there, and it’ll be terrific so we decide to drive to Las Vegas. And unfortunately it rained all the way, it was a rainy weekend. Las Vegas is made for peasants, it really is. I imagined this drive to Las Vegas, we had this reservation at the hotel, we would check into the hotel, and have a bath and then go and gamble a bit.

WADE: Civilized.

HOCKNEY: Yeah, and then go and gamble a bit, and then go over and some man will show you to some lovely table in this great big place in the Hilton and we’ll see Elvis. Was it like that? No, we arrived at the hotel. And according to Ken Tyler we had a reservation there and a reservation at the hotel and a reservation at the table for Elvis, and we get to the hotel at six o’clock and I’m beginning to think that maybe we are arriving a bit late. And I said, Yes, we had a reservation. Two rooms because Nick Wilder went. And he said, “Oh yes, there might be two rooms at about 9:30.” And I thought why would anybody check out of a hotel at nine o’clock at night. Where would they be going from Las Vegas. So I said what do we do. So he said, “Well, put your luggage down there, and there’s a casino.” And I was wearing a thick tweed suit ’cause it was raining when we left, and it really got hot there. So I thought, well maybe we’d better go over and check about the reservation for Elvis. We walked over to the Hilton Hotel and I said have you got this reservation. And they said yes, and this was about 8:30 and they said yes, get in the queue immediately. And I said, but it’s for the midnight show, and he said, yeah, you’d better get in the line now, otherwise you won’t get in. So I said what’s the point of the reservation. I mean, can’t we just stroll in at 11:30? “You won’t get in then.” So we had to start queuing. Still didn’t know if we had a hotel. Phone back the other place. Finally at nine o’clock they finally said, all right, there are some rooms. We had to leave Nick in the queue and we had to go back.

WADE: That’s terrible. How much were the tickets?

HOCKNEY: About 12 dollars each. And then they cram you in. We had to sit at a table, four girls and they were from somewhere in Missouri or somewhere and they’d taken No-Doz and were drinking Coca-Cola

WADE: They had taken what?

HOCKNEY: No-Doz, those pills you can buy in the drugstore for driving in case you doze off… Oh it was tacky, it was really tacky. We thought we would have champagne. It was horrible cheap champagne—really awful. Then we had to wait. And the only good thing is when the lights go out, and there is this build up, that, I must admit was fantastic. Really exciting. The moment he appeared was still pretty good, but then it all kind of faded.

WADE: What was he like?

HOCKNEY: Well he was dressed in a kind of white space outfit. He stilled looked pretty good really. But the thrill of it all is in retrospect, you know. It’s afterwards you think, oh I’ve seen Elvis in Las Vegas and it was terrific. But when you were there I mean, all the discomfort and everything. It was really tacky.

I went to see David Bowie in Long Beach. I was a bit disappointed in that really. I’ve never seen him before and I didn’t know his records, I’m not a great pop music lover.

WADE: Was everyone glittering?

HOCKNEY: There were quite a number of people were dressed up with tinsel on their eyes and all that. But I was a bit disappointed in him. I thought he would be more outrageous than he was. He was quite good, but I thought it would be a lot better. Ossie says he’s terrific.

WADE: He’s really into pop music, Ossie is?

HOCKNEY: Oh yeah, I took him to the Olympic Games, and I took him to the opera there. We went every night to the opera because the Olympic Games was really boring. I thought, I got the tickets for doing a poster. I’m sure it was much better watching it at home on the telly. The reason I stayed was because every night we went to the opera. And Ossie had never really been to the opera before and I was a bit dreading it, I thought, “Oh he’s gonna hate it.” And we saw the most marvelous production of Der Rosenkavalier and Ossie loved it to my amazement. At the end of the first act when the Marschallin is singing how her young boy has left her for some younger woman and life’s passing her by and how she realizes she’s getting old and everything, as the curtain closed Ossie turned to me and said, “I know exactly how she feels. ” And every night Burt Lancaster was there.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE JULY 1973 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.