DISCOURSE

Michael Abel and Tunji Adeniyi-Jones on Troll Art, Traditionalism, and Taking the Bait

It feels surprising that a medium as old as painting could remain the subject of ferocious debate, sparking a conversation about the troubles of contemporary art production and the vehicles that maintain it. But Dean Kissick’s November 2024 cover story in Harpers Magazine managed to do just that, monopolizing art world discourse for weeks online and at every downtown outpost. “I worry that it’s part of a wave of anti-woke edgelords who are doing anything that they can to polarize current discourse,” the architect and artist Michael Abel told Tunji Adeniyi-Jones in a conversation last week, just after their solo exhibitions opened at YveYANG in New York and White Cube Seoul, respectively. The two artists, who position themselves in a more traditional artistic lineage, got on the phone to decode the now infamous “Kissick essay” and talk about troll art, the old guard’s attempts to embrace the new, and how they bring themselves back to reality in a world moving at dizzying speeds.

———

TUNJI ADENIYI-JONES: How are you doing, man?

MICHAEL ABEL: I’m good, I just got back from Macau.

ADENIYI-JONES: How was the trip?

ABEL: Pretty crazy, I’ve never been there. I played roulette for the first time.

ADENIYI-JONES: But you weren’t there for very long?

ABEL: No, just for three days.

ADENIYI-JONES: Was that enough time, do you think?

ABEL: No. Have you been there?

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones. Pearl White Harness, 2024. Oil on canvas. 144.9 x 190.7 x 6.5 cm. 57 1/16 x 75 1/16 x 2 9/16 in. © the artist. Photo © White Cube (Frankie Tyska).

ADENIYI-JONES: No, I’ve never been but I asked because I was recently in Seoul for seven days, and that wasn’t enough time either. It was just starting to get really good when I was leaving.

ABEL: I’m going to Tokyo again on Sunday.

ADENIYI-JONES: You are? Oh, wow. I guess because you’ve got this show up you won’t be doing as much painting now, but would that kind of travel usually affect the way you work?

ABEL: Yeah, I think so. Particularly this past trip because I was moving around a lot. I was at Mt. Zao in Japan and then Macau. But I was trying to build some scenes in my head since going to all these new landscapes. But we should talk about these shows that we just had. Have you ever shown in Asia before?

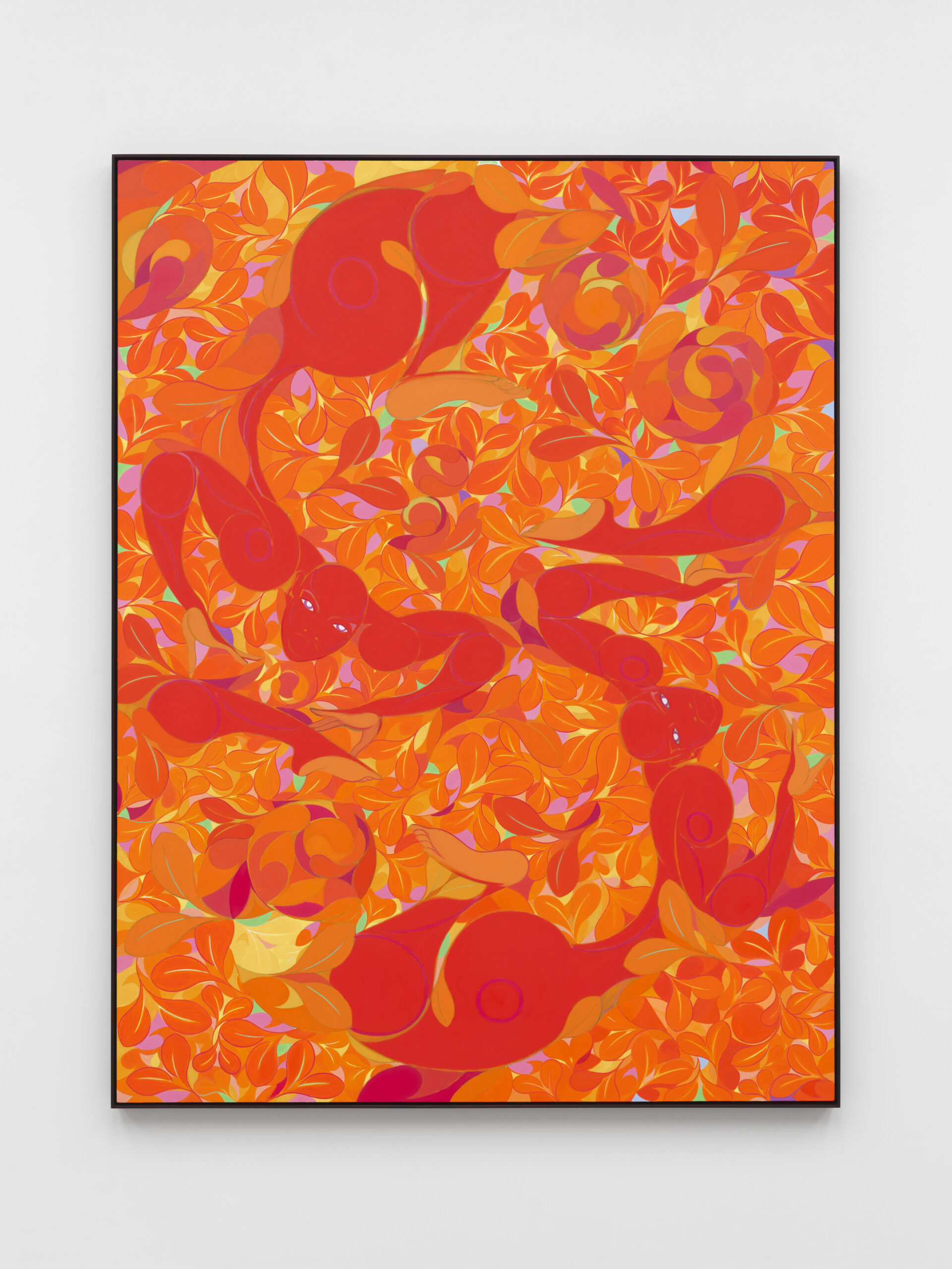

ADENIYI-JONES: Yeah, I had a show in Hong Kong with the same gallery in 2023. But with this show in Seoul, I did a lot of research before I went because there is such a comprehensive history of South Korean abstract painting. They have their masters, their masters have their museums. The teachers, the students, people who travel come back—it’s all about sustaining an aesthetic. So I tapped into that and I shifted to this pale pearl white and beige, soft tone, which is quite drastic for me, given how strong and vibrant the colors I usually use are. And it really hit, actually. A lot of people were like, “Wow, this feels so Asian. Why?” I was like, “Oh, I did the research.” I really wanted to make something that was responsive to the environment that people could tap into without knowing anything about me or where I was from.

ABEL: That’s cool. I didn’t do anything to quite that extent, but at YveYANG they have all these gold ceilings. From the very beginning, I wanted to make a series of paintings that had gold in them, so I had this gold gesso underlayer in everything.

Michael Abel. Before Christ (Death and Life), 2024. Oil and oil stick on linen. 30.5 × 22.9 cm. 12 x 9 in.

ADENIYI-JONES: How was that?

ABEL: I liked it, I’ll probably keep doing it. Historically, people have done it to try to simulate sunlight. I don’t think I was technically apt in that regard.

ADENIYI-JONES: It definitely had a really nice texture to it and it was distinctive in a way that I hadn’t seen before. It was clear that that was something new that you were bringing to the work for the show.

ABEL: For context, we met a few weeks ago to see this Chris Martin show at Timothy Taylor, and we both liked it. I think simultaneously we both realized how conservative we were when it comes to the tools and the mediums themselves.

ADENIYI-JONES: Yeah, in so many ways.

ABEL: I don’t know if it’s a purity thing or if it is just conservatism at its core, but I was thinking about people like David Joselit. He probably wrote the one of the most seminal texts about painting in the 21st century which of course embraced this type of hybridity with painters like [Wade] Guyton and—

ADENIYI-JONES: I’m glad you brought this up. I’ve been thinking about that show too. But the conservatism, how much of that do you think is ours or how much of that do you think is from our sensibilities developed in the household growing up? My mom is super conservative too, so it makes sense.

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones. Red Orbit Motion, 2024. Oil on canvas. © the artist. Photo © White Cube (Frankie Tyska).

ABEL: Well, my father was conservative at the end of his life but he wasn’t at the beginning. At one point, he was a hippie who lived in a cave in Hawaii. But I’ve been thinking a lot about technology, because it’s so present in our lives and there’s an inherent urge to try to incorporate it into what you do in order to be contemporary. I definitely do things that are technology-obsessed.

ADENIYI-JONES: Yes, me too.

ABEL: I guess painting seems like a prehistoric medium that doesn’t need to be redefined, in terms of tools and the shapes of the canvases and the medium. But what does need to be redefined is the subject or signals or symbols. And I think new aesthetics have been defined not through technology, but through certain politics or identities. And that isn’t to say that technologies didn’t lead to those conversations of politics and identity, but that has been interesting to me. Did you read that Dean Kissick article?

ADENIYI-JONES: Yeah, I did. Shout out to that, shout out to him. It’s really a rare piece of work, such focused art writing on contemporary painting and what’s happening right now. That type of writing was prevalent like 10, 15 years ago, but now it’s super scarce. Did you see that David Salle had an exhibition at Gladstone? I went to see it and I thought, “Oh, these look a bit weird. Something seems off with these paintings. Are they bad?” And then I left and then I read about it, and it turns out that he had used AI to create the ground for it. He used an algorithm to – “Make David Salle paintings.” And then he painted on top of that. It really made me pause. But David Salle has been painting for over 50 years or something. I could see myself at a much later point in my life playing around with some new ideas. You could maybe argue that because now things are speeding up, maybe that comes sooner.

ABEL: It was a silly idea, though. Surely these were meant to be kitsch.

ADENIYI-JONES: Well, yeah. But he’s had a lot of great ideas in his time.

ABEL: That’s on some Richard Prince print-out-the-Instagram-photo.

Michael Abel. Before Christ (Mickey), 2024. Oil and oil stick on linen. 45.7 × 61 cm. 18 x 24 in.

ADENIYI-JONES: Yeah, that’s also its charm. It’s like the David Hockney iPad paintings. I remember strongly disliking those when I first saw them, but with time I’ve come to understand the artistic mind, having gone through decades of exactly what you and I are describing right now. This moment of being like, “How is technology moving so fast but this medium we’re using is so slow?” And why are we so attached to it at its more pedestrian rate?

ABEL: And at the end, they suck.

ADENIYI-JONES: I’m sure David Salle saw them as experiments, or maybe he doesn’t even think of it in the same way that we do because he has so much work behind him. I’m sure that we’re prolonging something, and at some point we’ll get there and it’ll probably be a bit strange and then we’ll decide whether to resume form or pursue further experiments or whatever.

ABEL: Yeah. Well I did like the article, but it had a hint of “the good old days” in there. I think this heyday period led to a bunch of really bad art which we could have really, really done without as well. But at the end of the day, it’s very helpful for critics to try to synthesize something that’s happening, particularly in the market. Because the market goes rogue so often,there’s a history of critics course correcting them. One thing that was interesting was he [Kissick] chose a lot of artists that were making extremely layered work, which he did on purpose. It wasn’t just about technology; it was contemporary in medium and subject.

ADENIYI-JONES: Yeah. As someone who would potentially fall into the category of being one of those artists or painters that would be associated with hyperproduction, working with a big global gallery, I did wonder if someone like has the capacity to be satisfied ever? Maybe that’s the point. I enjoyed reading a bunch of [Peter] Schjeldahl stuff, but he was also never really quite satisfied. From the artist’s perspective, it’s tough because we’re dealing with a viewpoint that’s so hard to please.

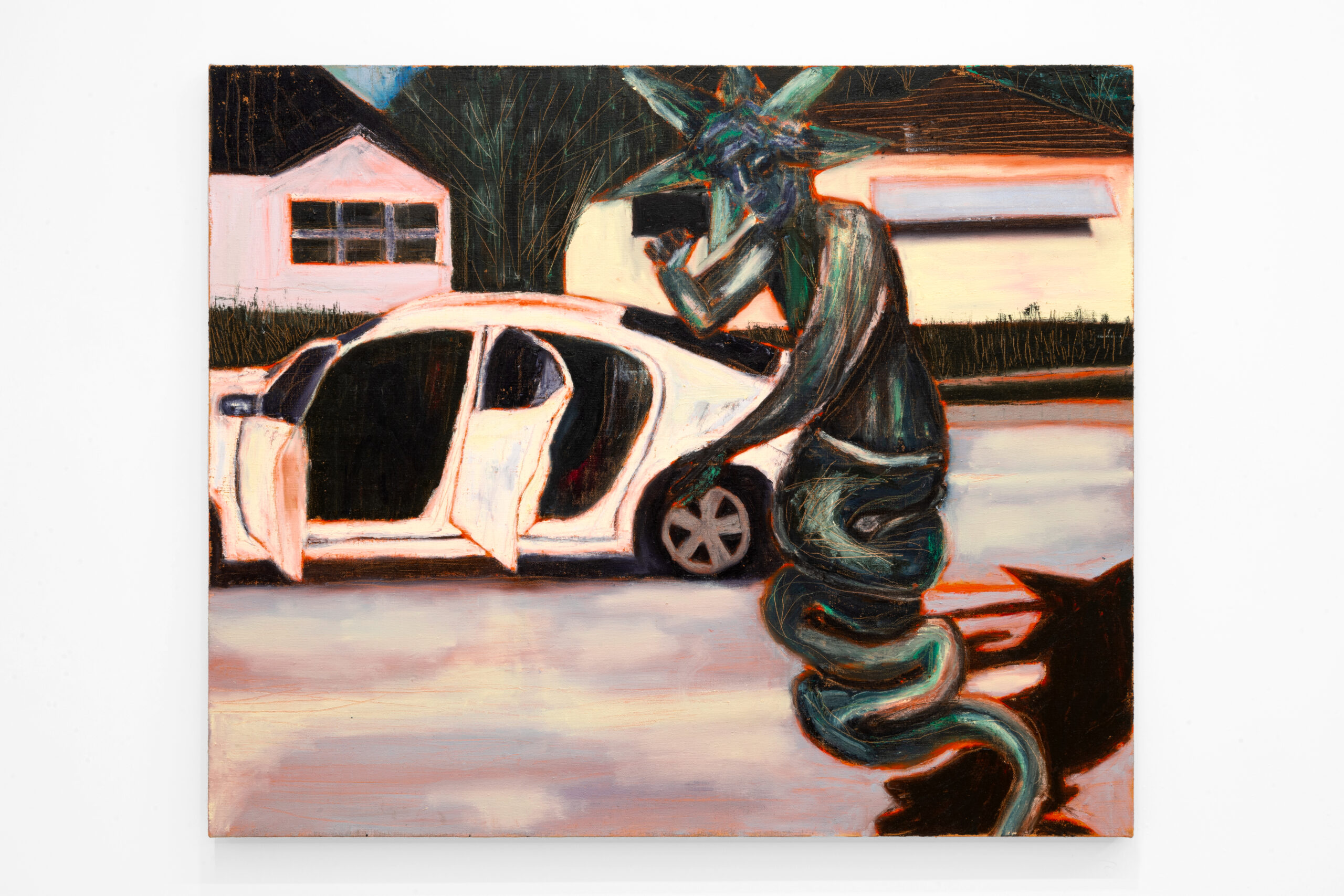

Michael Abel. Lady Liberty Bounce VO2, 2024. Oil and oil stick on linen 101.6 x 121.9 cm. 40 x 48 in.

ABEL: Did you feel attacked by the article?

ADENIYI-JONES: Not attacked, but I certainly felt implicated and self-aware. Aware of the monotony that goes into my work, and the rigorous routine, schedule and turnaround, I can identify with that. But we all have our reasons and our purposes and our why’s. I’m just like, “Where does he actually find a point of satisfaction or understanding with an artistic perspective of what it means to be an artist today, trying to survive in 2025? And how do you sustain it?”

ABEL: Yeah. I worry that it’s part of a wave of anti-woke edgelords who are doing anything that they can to polarize current discourse. Because that’s what you do in culture now, which to me is the opposite of progress.

ADENIYI-JONES: Of course.

ABEL: You take one step forward, one step back, and then you’re just fucking stagnant. So I try not to be polarized in that regard. If I was 18 years old and more angsty than I am today, I would be really drawn to that type of conversation. In my head now it’s just like, “Take the good, leave the bad and then move forward.” Especially when you trigger the market like that.This isn’t “zombie formalism.” This is different—this is political. It’s not just about the market.

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones. Blue Violet Dive, 2024. Oil on canvas. 178 x 193.2 cm | 70 1/16 x 76 1/16 in. © the artist. Photo © White Cube (Frankie Tyska).

ADENIYI-JONES: I think that it’s a “can’t live with, can’t live without” kind of relationship. I’m smart enough to know that you can’t expect to not have to contend with this, but also dwelling too much on the bad, or maybe deriving a sense of vindication from identifying it—ego comes into it. But you need ego as a writer, it’s why anyone even cares. It’s a really tricky conundrum.

ABEL: So where do you think painting’s going to go now?

ADENIYI-JONES: I think that there is a new audience burgeoning for this slightly new technological advancement, there’s all of the children of all the collectors who are involved in up-keeping what I would consider to be the bulk of the art market through Europe, Asia, here. So I think there’s going to be a new market for a new type of thing that will run concurrent with what you and I are talking about. And I think that will not need to be a threat to, or jeopardize, either side unless people paint it as such, and people obviously will pit it against each other. But we’ll probably also see more hybrid digital art. Someone who’s sitting at a desk operating a robot that’s making a painting in a gallery and that’s the whole show. And then it’s about maybe more the spectacle, the moment, the experience of it. I think that there is a large appetite for this already, and that’s going to coincide with the large developing populace in general. I think we’re going to see some new shit.

Michael Abel. Moonlight (After Munch), 2024. Oil and oil stick on linen 101.6 × 101.6 cm. 40 × 40 in.

ABEL: I hear you. The art world is strange. There’s such a strong and long history to these things and it hasn’t changed that. With painting in particular, it has stayed quite consistent, besides the subject that is.

ADENIYI-JONES: There is always money that’s waiting to be thrown into something new – is what I’m trying to articulate. Like, the dude who bought [Maurizio] Cattelan’s banana at Sotheby’s.

ABEL: Right, like online troll-art, but I feel like that’s just also futile. Those stunts will always happen in the background.

ADENIYI-JONES: it’s the background for us, though. For some people, that was the coolest shit in the world.

ABEL: I know we’ve been using the word conservative, but maybe we should find a different word.

Michael Abel. Forbidden Mickey, 2024. Oil and oil stick on linen. 101.6 × 121.9 cm. 40 × 48 in.ADENIYI-JONES: Traditional?

ABEL: I think that one thing that is inherently different now in this post-Warhol, post-Koons world is, I find painting extremely personal, which is why I started painting again to begin with. It wasn’t market-driven, it was some sort of reckoning for myself. And I have no desire to promote this struggling, tortured artist individual type.

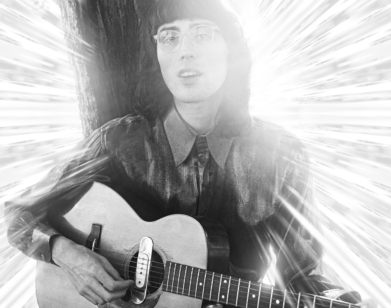

ADENIYI-JONES: Absolutely not. Me neither. You first showed me a painting of yours on Instagram around when we first met in 2018 or something, and I still can’t really pinpoint what it is that I enjoy

about your work so much. There’s something that has always translated very directly to me, maybe the combination of the graphic quality you’re using and the subject matter that creates this thing that’s hard for me to articulate, but I’m really drawn to it.

ABEL: Thank you. For the record, I want to say I made some of the worst paintings in my life trying to follow a contemporary moment in technology. I definitely explored it when I was younger and failed.

ABEL: I guess the word that I was looking for instead of conservatism is lineage, and I think lineage notates slow progress, where you’re taking something that is good and then adding to it and changing it slightly. I’m just quite literally obsessed with painting and I love it a lot. But likewise, obviously I love your work and that’s why I wanted to have this conversation. I was at your first solo show in New York, 2017 after Yale, and it’s indescribable why you are drawn to something, which is the magic of it.

ADENIYI-JONES: Right, because it’s based on the senses and on the other aspects of how we experience the world. It’s such an isolating thing though, man. It’s a confusing thing, as artists. We need our alone time, but we need the rest of the world. I definitely need a moment where I’m just fully in my body and my physicality or something to be able to do something. Maybe it’s to bring myself back to reality.

ABEL: Yeah, I feel you. I think you’re describing the subdued nature of your life.

ADENIYI-JONES: For sure.

ABEL: With this last show I just made, subdued subjects were something that I was extremely interested in, which is why I was looking at artists like Edward Munch who were literally quite literally tortured.

ADENIYI-JONES: Yeah.

ABEL: My life is really busy so I fit it in where I can. But I think it’s good for your body to feel nothing.