STUDIO VISIT

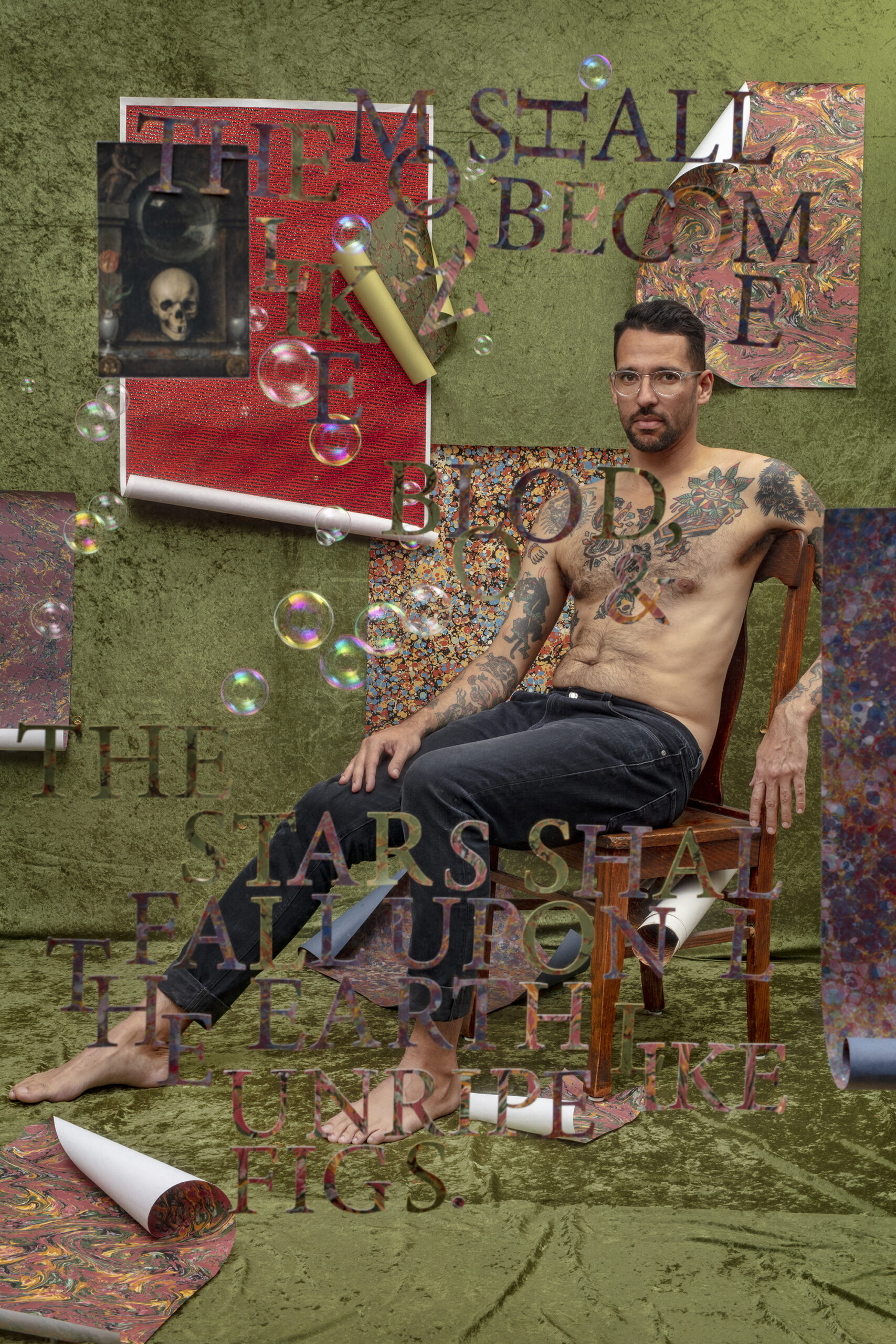

Meet Rachel Stern, the Photographer Reinterpreting Oscar Wilde’s Salome

Crushes, colleagues, grandparents, lovers, friends, acquaintances, and even pets serve as subjects in photographer Rachel Stern’s exhibition, One Should Not Look at Anything, on view at Baxter St. at the Camera Club of New York. Though Stern’s models are dressed simply—they wear black or pose nude, according to their preference—the backdrops behind them reflect a maximalist sensibility. In Stern’s words, the exhibition examines “queerness, fatness, and the intersection of those two ideas as they relate to personal and societal ideas of desire,” and by tapping her own social network for models, the artist has constructed a web of intimate connections legible only to herself. But the exhibition’s investigation of desire achieves a broader resonance. In the foreground between the camera and the photographer’s subjects, we see text from Oscar Wilde’s Salome. This isn’t the first time Stern has deployed the literary canon in her photography practice—her last two exhibitions were based on Arthur Miller’s The Crucible and Voltaire’s Candide, and her 2016 series, Yes, Death., also references to Wilde’s work. Shortly after the opening of One Should Not Look at Anything, Stern dialed in to share what Salome means to her, discuss the relationship between fatness and desirability, and tell us what it was like to photograph the women in her own bloodline.

———

ELEANOR VEITCH: Could tell me a little bit about your work up until this point. I’m curious about the projects that preceded One Should Not Look at Anything.

RACHEL STERN: I live half my life as a very traditional black and white film photographer out in the world. Then I have this other part of my practice, in which I build constructions in my studio, photograph them, and then often turn those photographs into installations. That part of my practice has been the main way I’ve been making work since 2015, which is when I started making immersive environments. That’s also the moment when my practice really started to deal with this idea of translating a piece of literature, or translating some cultural or historical event through these kitsch materials of my studio and representing it in an image-based context. In 2018, I made a project called More Weight. That was the first time I really thought about a specific piece of literature as the foundation for a body of photographs. More Weight is a line taken from Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible. The show was at Brandeis University during the Kavanaugh confirmation. After that, in 2020—in the middle of the pandemic, pre-vaccination, immediately following the murder of George Floyd—I did a show at Ortega y Gasset Projects in Gowanus that was called This Terrestrial Paradise. That project imagined an epilogue to Voltaire’s Candide, which is this fairytale about optimism versus pessimism that ends with this line, “Let us cultivate our garden.” I imagined the garden that comes at the end of Candide. It was the first project of mine with text in it. After that, I became really interested in the idea of text being embedded as part of an image. In the middle of all of that, my heart was terribly broken, and I began to think about Salome in the same way that I thought about The Crucible during the Kavanaugh confirmations and Candide during the heart of the pandemic. My heartbreak led me back to Salome.

VEITCH: When did you first read the play?

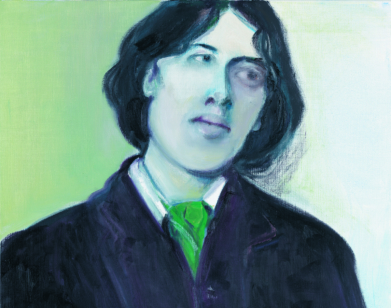

STERN: I was a smarty-pants English student. I was bad at everything else, but I liked literature, which is funny because I’m dyslexic and a very slow reader. One summer in high school, I was outraged by the reading list for the English course I was taking. It was made up of two books. One of the books was The Pact by Jodi Picoult, which I hope you’ve never heard of. It’s a dumb, upsetting book about straight people being horrible. The other book was The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde. Reading that was a formative experience. I remember storming into class on the first day of school and being like, “How dare you assign these two books in one breath? These are not the same thing.” Very quickly thereafter I started reading any Wilde I could find. So Salome has been a story that has always kind of lived with me. Salome is this intolerable Jewish princess, this princess of Judea that everyone finds intoxicating and annoying and revolting. Which is something that I identify with—as a loud, fat, assertive Jewish woman—in terms of the way my presence is generally treated. She navigates the world as this character who’s treated as a harlot and a virgin at the same time, two labels which are both true and untrue, infantilizing, and fundamentally irrelevant. She’s stuck in the trapped position, she’s sexualized in one direction or the other no matter how she behaves. I think what was most exciting to me about the play is this idea of getting what you want even if it means destroying the thing you want—or yourself—in the process. Salome meets John the Baptist and falls in love with him, or at least falls in lust with him. In her obsession to get to him, she acquires the ability to kiss him by cutting off his head and kissing his severed head. Then she’s killed for doing that.

VEITCH: Can you tell me more about how this show further develops those ideas in the play?

STERN: So the first picture I made was the self-portrait, and it’s behind text that says, “If thou had seen me, thou would have loved me.” I felt very strongly about putting those words over my body. I think they relate a lot to my identity surrounding queerness, fatness, and the intersection of those two ideas as they relate to personal and social ideas of desire. Salome is saying that to his severed head. She’s holding his severed head, and she’s like, “If you would have actually seen me, you would’ve loved me, and we wouldn’t be in this position where I had to cut off your head in order to kiss you.” Which I feel often.

VEITCH: So relatable.

STERN: Something I talk to my students about a lot and often think about in my work is the question, “What do you have special access to?” One thing I have access to is a body that is not commonly associated with beauty or desirability. I think in the landscape of contemporary photography there’s often a somber element in the display of a fat body, or something very comedic. I love funny art, and I hope that parts of my show are funny. But I really wanted to hold a space that was the same space that I see other women and femme photographers being able to hold with more normative bodies, and I wanted to have these really productive feminist discussions. I think a lot about the position of a “fuckable body” in a feminist argument. I think if you look at the canon of feminist art, there’s an opportunity to attack patriarchal ideas through a body that is permissible. So I was interested in inserting myself into that chorus in a body that maybe has less permission and complicates the argument.

VEITCH: There’s such a wide range of body types and ages represented in these photographs. I think there’s even a dog or two.

STERN: I think of my studio very much as a spider web. If you came close enough to me in the two-and-a-half years I was making this work, I would try and grab you and stick you in something. What was really exciting about this project was that people were sitting as themselves. So I was able to let people style themselves. The only rule was you had to wear black or be nude to your own comfort. So if somebody’s nude, that was their choice. The models are all people I know and am close with, including some really fun ones. My best friend from high school is Korean and lives in Seoul, and I only get to see her once every five years. She happened to come to New York last fall, and I was like, “Bring a black outfit.” I also photographed my grandmother, who’s 93.

VEITCH: I noticed that in some of the photos the subjects seem to be inviting attention, while some of the other subjects are a bit more restrained. Do you want viewers to perceive some subjects differently than others? Or do the subjects themselves determine how they want to be seen?

STERN: Mostly the subjects hold their own space. For me, portraiture is an honorific form. I want people to look and feel like themselves. I want them to feel beautiful. One of the most surprising things to me was that my mother posed completely nude. In a million years I would never have guessed that that was going to happen. She came to my studio to do the picture, and she brought all these black clothes with her. My sister, who’s a dentist, is also my studio assistant, which is very nice. So my sister and I were setting up for the picture, and my mom came in, and she was like, “Guys, I think I’m just going to be nude.” My sister and I were both like, “Rock and fucking roll. That’s cool, Mom. Do it.” My mom is in her 60s, she has gray hair. She’s incredibly beautiful, but she’s not the kind of person we normally see posing in the nude. I’ve had so much fun having people come in for studio visits and be like, “That’s your mom? She’s so hot.” I’m like, “Hell yeah, my mom’s hot.”

VEITCH: Do you see the subjects as objects of desire? Or, in some cases, are they the ones desiring?

STERN: I think it’s definitely a two-way street in every instance. Because I hope that everybody looks good and can be desired. But also the patron saint of my studio—an artist I’m deeply committed to—is the surrealist photographer Claude Cahun. Cahun is a gender-queer Jewish surrealist photographer, but they weren’t part of the surrealist movement because the surrealists were chauvinists. Something that I love about their self-portraiture is that they’re always looking straight into the camera. They’re always making aggressive eye contact. They’re in costume as an angel or an alien. You can tell that the wings are tinfoil, you can see that the backdrop is a blanket, you can see all the edges, and you can see the gems glued to the costume. But there’s this eye contact that’s like, “Look at me and tell me I’m not an angel.” In almost every picture, my subjects are making direct eye contact with the lens. That’s a reference to Cahun’s work, this ability of the subject to address the audience from a position of power.

VEITCH: Do you have a favorite piece?

STERN: For emotional reasons, I’m very connected to the first one that I made, that first self-portrait. That picture really was me changing my own life. So much of my life changed through the making of this body of work. Throughout the entire process, I didn’t speak to the person who had broken my heart so badly. It was unrequited love, that’s important to say. Then they came to the opening and I was neither elated nor upset. I was completely past it, and it was nice to see them. It didn’t affect me. I felt so proud of the pictures in that moment because they had brought me to that point. That’s the really beautiful part of this project. It really is my life in an earnest sense. But if I had to pick a favorite, there are two portraits of my sister in the show. Right before the pandemic, she was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 28. So we had a really wild pandemic, undergoing mastectomies as hospitals were closing down. It’s just been a wild ride. She’s in great health now, we’re very lucky and happy. Both portraits in the show were taken in the days immediately following various procedures. One of them is a large, full body portrait. In that picture she has two black bandaids above her nipples and one above her belly button. It was really cute—they’re actually flesh colored bandages. But because she knew the dress code was black, she bought black band-aids to match. My sister and I look at that portrait and we know exactly why those bandages are there. But it’s impenetrable, no one can possibly understand it. These bizarre bandages are just a completely chaotic element. It looks like she was trying to cover her nipples and missed. But it’s also just an important moment, us being together. So that one means a lot.

VEITCH: I remember noticing the bandages and not knowing what they meant.

STERN: They’re completely baffling.