Mars Hobrecker’s Brooklyn Studio is Full of Chairs and Cowboys

“People section off their bodies in really strange ways,” says Mars Hobrecker, the Brooklyn-based tattoo artist known for his highly sought-after large-scale designs. “It makes sense, except when you end up with all your horrible tattoos from one phase of your life on the same leg. It becomes this really clear chronology.” In light of the fact that online sales of stick-and-poke kits have soared on Etsy in recent weeks, let the artist’s words serve as a forewarning: spread out your corona tattoos. Hobrecker, who the foresight to heed his own advice, managed to spread out the ink from his teenage years in Nova Scotia, avoiding the prospect of a single embarrassing appendage. “It’s a relief that they’re not all hanging out together.”

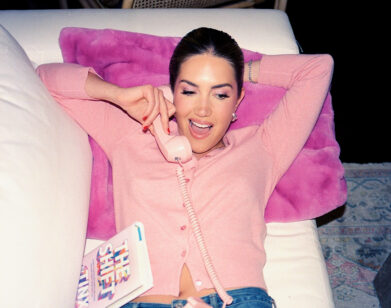

Some of Hobrecker’s tattoos are allowed to hang out, though. A constellation of bondage figures lounge together on a thigh, a bunch of bananas dangle from an arm. “It’s all about building off of a person’s collection. I like to tuck a new piece near something—a curve of the body or another tattoo—that it flows well or mirrors an existing shape,” he says, one finger idly stroking the scarab beetle that rests in the dip of his clavicle. We’re sitting in Hobrecker’s Bushwick studio, a large, sun-filled concrete space at the far end of several long and dark hallways littered with paint cans. It’s warm in all ways—mellow soul music plays, someone in the corner is having a piece of candy inked into their palm, and broad-leafed plants tinge the white walls a minty green as they reflect the daylight.

In a sea of faint lettering and delicate botanicals, Hobrecker’s designs are unabashedly bold. Rodeo cowboys parade around on one another’s backs; naked, ripple-thighed women lie in joyful tangles; pyramids of bawdy beachgoers teeter to and fro on chests and thighs. His designs, intimate and raucous, are certainly a commitment; the smallest are around the size of a palm. “To shrink them would risk blurring their expressions. I would have to sacrifice so much movement and detail, and that’s not worth it,” he says definitively. Tied up in this stylistic conviction is Hobrecker’s larger philosophy, which has positioned him at the heart of New York’s queer tattooing community: that the magic of a tattoo comes from relinquishing yourself to the process, not from arriving at the studio with a vision of how you want to look. “The people I work on often have complicated relationships to their bodies,” he says. “That’s something a lot of artists try to just push aside. They prefer to focus on their design, not the person receiving it.” While the normative tattoo scene is notoriously hostile to diverse physiques and skin tones, it’s Hobrecker’s mission to ensure that his work is a celebration, and a reflection, of the bodies that carry it.

It makes sense, then, that for Hobrecker, the importance of a tattoo stems less from aesthetics than from making a genuine connection with the artist in the moment—choosing on the spot from among piles of flash, surrendering to the whirring machine. After all, when a quote ages out of its gravitas or a relationship ends, an inky reminder will forever remain. Better, then, to nestle into his green velvet couch without any expectations, flip through hundreds of illustrations of buxom dancers and wasp-waisted dandies, and wait for one to grab you by the hand and take you for a ride.

Though Hobrecker has attained a sort of cult celebrity status from his ebullient illustrations, it was pain and performance, rather than a love of illustration, that led him to the art form. “I didn’t really draw before I started tattooing. It was never something I was interested in,” he says as we scroll through his designs on an iPad. One, of a woman in an armchair with a bird perched on her finger, catches my eye. “It was the sensation, more than the image, that I was drawn to.”

Recently, Hobrecker overcame his distaste for drawing when he was tapped to design a powder blue cowboy-covered suit for Canadian country boy Orville Peck in collaboration with Union Western Clothing. His illustrations, though undeniably retro, managed to reimagine the cowboy from stoic and tobacco-stained to rough n’ ready for a romp in the hay.

Before we were all gripped with the irresistible urge to poke the tiny green germ emoji all over our bodies, Interview dropped by Hobrecker’s studio to see where the real magic happens. From cowboys to Catholic school, Mars Hobrecker leads us down his favorite rabbit holes for tattoo gold.

———

MARA VEITCH: Tell me about your tattoos. Do you have any that you regret today?

MARS HOBRECKER: I think the tattoos I hate most now are the ones that had a lot of meaning to me when I was 18. The ones I picked on the spot because I thought they were silly and cute are the ones that I still really love.

VEITCH: Do you remember when you got your first one?

HOBRECKER: It back in Halifax [Nova Scotia], where I’m from. I snuck out during lunch at my Catholic school.

VEITCH: You were rebellious …

HOBRECKER: I was definitely a little scene kid. I always wanted tattoos.

VEITCH: What does it look like?

HOBRECKER: Ugh, it’s some stupid script on my ribs. It was in my own handwriting, which I should not have done. I practiced writing it on a piece of paper during my last class before lunch.

VEITCH: Did you hide it from your parents?

HOBRECKER: Oh yeah. I think I had at least six tattoos before my parents knew that I had any. I placed them very strategically, so that I could even be in my bra and underwear and no one would see them.

VEITCH: That was clever.

HOBRECKER: I think I even changed out of my uniform before the appointment because I was a little ashamed. When I took my bra off I had those indentation marks, and I told the artist, “Okay, put it right in there.”

VEITCH: The internal monologue at that age when you’re doing something you shouldn’t be is priceless. What is the tattoo scene like in Halifax now?

HOBRECKER: It’s really cool. A friend of mine just opened an all-queer tattoo shop there, which is so exciting. That’s not something that I would have imagined would happen there when I was a teenager. It’s really exciting that these little queer shops are popping up all over the place.

VEITCH: Did these smaller shops mostly get their start on Instagram? Has it democratized the tattooing world?

HOBRECKER: One hundred percent. There was definitely a Wild West moment in Instagram tattooing a few years ago. Suddenly everyone was getting their work seen. But now Instagram prioritizes branded content and is censoring a lot of artists—who are queer, POC, or they’re fat, or they’re talking about sex work—and they’re not getting that visibility. It’s definitely harder for new tattooers to gain an audience now.

VEITCH: Can you tell me about a few of your tattoos?

HOBRECKER: I have some bananas on my arm. I’m allergic to bananas. It’s the only thing I’m allergic to. I also… accidentally … have like a porn-y section on my leg that—

VEITCH: It’s a region?

HOBRECKER: Yeah, it’s a collection of bondage pieces tucked together. [Laughs] It kind of just happened. Whenever I wear shorts, I remember like, “Oh, yeah. That’s there.” So those ones are also a little silly.

VEITCH: Your flash is so joyful and physical—lots of cheerful, campy figures interacting with one another. Where do you find inspiration?

HOBRECKER: All of my illustrations are based off of old photos. I was working at an archive before I started tattooing full-time. I love to re-contextualize those images a little bit. I went through a period where I was drawing a lot of chairs. I wanted to be a furniture designer when I was a kid.

VEITCH: Are chairs your specialty?

HOBRECKER: Well, I love drawing them, but I don’t actually love tattooing them so much. Too many straight lines. It’s very stressful.

VEITCH: That’s funny.

HOBRECKER: People don’t have straight lines. Bodies aren’t super precise; we’re round, for the most part. But with inanimate objects, that’s just what it looks like.

VEITCH: Do you worry about messing them up?

HOBRECKER: Well—and this doesn’t happen often— if you mess up a chair leg, the whole tattoo looks really bad. But if a person’s leg turns out slightly wider than you’d planned, you can kind of embrace it.

VEITCH: Are you drawn to certain eras? What is it you look for?

HOBRECKER: I go down rabbit holes where I just look at hundreds of photos of one specific thing, the ways that people hold themselves, or the ways that people hold their hands, for example. I generally don’t tattoo anything more recent than the 1950s. Usually I’m looking for imagery from the Victorian era through the ’50s. So, lots of dancing, lots of western imagery.

VEITCH: Were you making art before you started tattooing?

HOBRECKER: I didn’t ever draw before I started tattooing. Honestly, drawing bores me. My art practice has generally been performance-based. For a while, I was doing a lot of human pin cushion-type stuff dealing with pain and physical sensation. So, I got into tattooing less because I liked the imagery and more because getting tattooed gave me a lot more control over my body. I wanted to be able to do that for other people.

VEITCH: And you picked up the drawing part as you went along?

HOBRECKER: Yeah. At first, I would just learn how to draw the things that my friends were asking for. Someone would ask me for a lion, and I’d be like, “Okay, I guess I’ll learn how to draw a lion.”

VEITCH: Do you have a stance on whether a tattoo should signify something?

HOBRECKER: Everyone feels different about this. Personally, I feel like there’s big meaning in me just having to sit with myself and commit to changing my body in some way. The experience is on a totally physical level. You just have to trust your artist, and you also have to trust yourself to be like, “This is something that I want that’s going to help me.”