Up Close and Personal With the Artist Marlene Dumas

I first met Marlene Dumas in the summer of 2017 in Amsterdam, where she has lived for the past 43 years. I had come to talk to her about contributing to an exhibition I curated celebrating the writer James Baldwin. For my show, Marlene expanded on her fascinating “Great Men” series, a dramatic group of ink portraits she began in 2014. In her images of Tennessee Williams, Marlon Brando, Jean Genet, and Pier Paolo Pasolini, among many others, Marlene created heartfelt works about gay or bisexual cultural figures seen from a different perspective—Marlene’s perspective—that made those familiar faces somehow more intimate. Their aliveness was palpable.

After that, Marlene and I stayed in touch. When Interview called to mark the publication of her recent book, Marlene Dumas: Myths & Mortals, based on a suite of ink wash and oil paintings that she recently showed at David Zwirner in New York, I welcomed the opportunity to talk. I particularly wanted to hear about the amazing trajectory that her life had taken: from growing up under apartheid in South Africa to life among “Europeans”; the development of her skills as an artist; and the rewards and challenges of being a working mother and now a grandmother.

———

HILTON ALS: Darling Marlene, are you in your studio?

MARLENE DUMAS: I am in the studio, but I’m not painting at the moment. I’m preparing for all of these lectures I’ve been asked to give. I’ve been going through my notes and newspaper clippings from recent years that I’ve cut out.

ALS: When you make a book of your paintings, as you’ve just done with your Myths & Mortals monograph, do you feel it’s a chance to get intimate with the work?

DUMAS: Yes, because before that, the paintings are really just in my head or how I remember them or the experience of making them. Growing up in South Africa, I mainly saw paintings in books. Art history came from books. When I first arrived in Europe to see certain works, be it van Gogh or Rembrandt or modern art, I’d never seen them in the real before, and suddenly I saw how small Girl with a Pearl Earring is, or that it’s really about scale and color. When I’m in the studio with my paintings, I’m almost sitting on top of them. Some of that intimacy gets a bit lost when they go into a gallery. The gallery can be a cold space, not a home space. And I do think, “Oh, these poor little things, can they still survive?” So that’s scary and alienating. But a book has an intimacy in that you can hold it in your hand. Of course, in a book, it also happens that the big, tall paintings become small, and the small paintings start to look bigger.

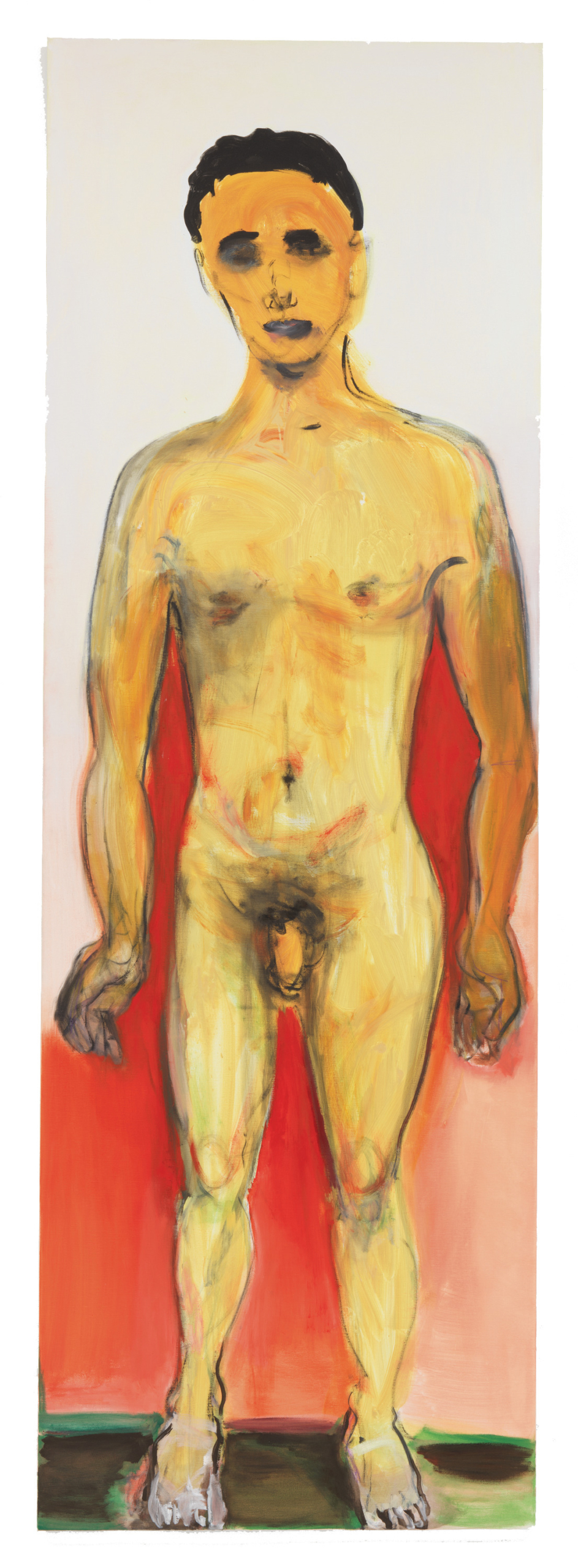

ADONIS, 2017.

ALS: I want to go back to what you said about visiting Europe after growing up in South Africa. How old were you when you took that trip?

DUMAS: I was 23. I had come to do a master’s at the university [Ateliers ’63]. I had thought, having gone to school in South Africa, that I knew all about art. But when I got to Europe it took me a long time to appreciate some of the old masters because I really didn’t know what to do with them—it was all angels and crosses and that sort of imagery. I was suddenly in museums filled with art, and I couldn’t deal with that. [Laughs] Instead I went looking for all of the banned books. I went to porno. I went to see all the things that were censored and that we weren’t supposed to see. So much was banned in South Africa because of the politics.

ALS: What was banned in particular?

DUMAS: Well, Nelson Mandela had been in the prison for so long and you weren’t allowed to see pictures of him. Those were banned, and many other images as well. Articles on politics were banned. All the films were censored. You never knew if anyone actually went to bed with one another or not! In fact, you never knew if something had been cut out of a film! So for me, Holland was so much about seeing unbanned things.

ALS: What did that feel like to you?

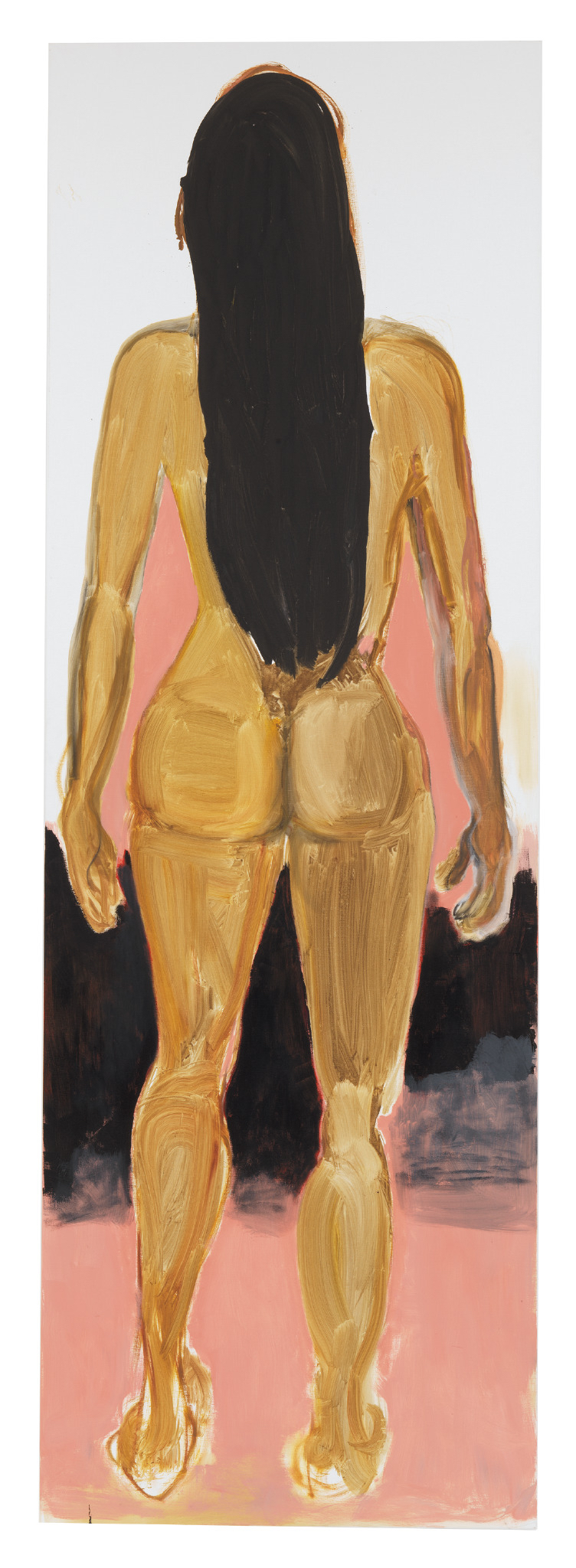

AMAZON, 2016.

DUMAS: It feels like such a silly word to use, but it was liberating.

ALS: That’s not a silly word.

DUMAS: It was also liberating as a woman. In Holland, women young and old would sit in the bars. In South Africa, women were not allowed in bars. Even beyond the segregation of black and white, as a woman you could only sit in a lady’s bar or the lounge. You sort of forget these things because as students we still drank and got drunk at times and we went to films although they were censored. But the whole bar culture in Holland was such a nice surprise.

ALS: I remember that when I came to Amsterdam to visit you, we talked about how your mother was political in the sense of not treating people badly. Your mother didn’t permit racism in her home, which was a big thing for South Africa at that time. That’s not to be underestimated. Did you realize when you came to Holland how different your mother was?

DUMAS: Yes, but we were still living in apartheid, and she wasn’t political in the sense of defending people’s lives.

ALS: But her stance against racism even at home is, for me, a political choice.

DUMAS: It’s true. But I would sit at the dentist and think, “He’s going to hurt me.” And then I would think of the people who were tortured for their beliefs and remind myself that I was just a coward who hadn’t yet done anything. But I was sensitive to these higher ideas—not that I was out to save the world.

ALS: You didn’t want to save the world, but you didn’t want to fuck it up more. Did you start making art when you were living on your father’s vineyards?

DUMAS: It wasn’t high art. I could do cartoons, and I probably shouldn’t be too proud of them. I could do girls in bikinis—these sexy Playboy types of cartoons. I could draw them very quickly. I never drew from life. The two books I grew up with were the Bible and the Brothers Grimm. They were all quite grim. I drew all these things I never really saw. I would draw women with these big evening dresses. It was part of these little stories in my head. Later, when I went to art school, they told me to get rid of all of that. In a sense I understood: If something is too easy or cliché, you should take it out. But then I thought, “Well, why can’t I make art about that? Why can one have love songs that are so touching and beautiful, but there can’t be paintings about that?” Maybe it really isn’t possible, but I’m still trying!

ALS: It is possible. You’ve done it. So much of your work deals with storytelling, like these recent paintings about myths.

DUMAS: There was a time when I was so interested in gesture that I thought I wanted to be an abstract expressionist. But I knew I couldn’t do that because there was always an aspect of language that I needed. That’s why my titles are so important in my works. That’s also why I brought the figure back in.

ALS: One of the paintings I love is “Protruding” [2018], which is of a nipple. I feel like you’re an artist who is discovering all the time. Even when you were growing up, you were seeing things in the world that would leave an impression.

DUMAS: I did not grow up with an artistic background. I had a teacher that I didn’t like in the least because he tried to tell me how to draw. I didn’t draw the way he wanted me to, and this was when they would hit you on the hand with a ruler. I got in trouble for not drawing the right way, but I wanted to have the freedom to create my own world.

ALS: You’re right to have resistance against people limiting you.

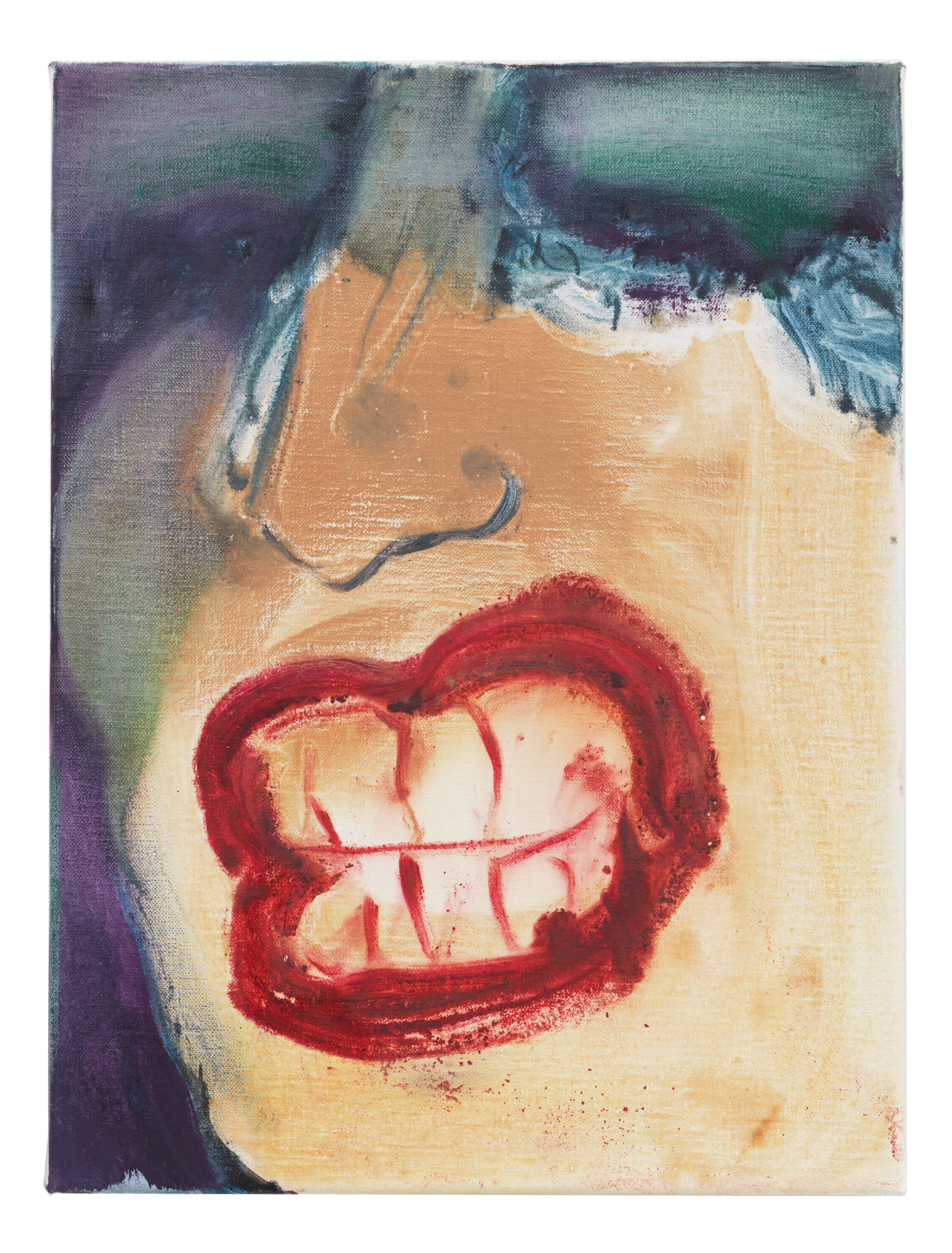

NIPPLES, 2018.

DUMAS: And yet, I have a tendency to feel guilty. That’s to do with my African background. Guilt is not a very good sentiment. But anger can be a helpful emotion. For example, if I read a stupid critique of my work, I get upset and then I feel bad and then I think, “Maybe I should do more of what they say I shouldn’t do.” It’s like when I painted babies [“The First People” series, 1990]. It wasn’t because I loved babies so much. I’m actually scared of them when they’re very small, so for me it was a challenge. Who paints babies? It’s like what you’ve said about Toni Morrison: No one was writing on a subject, so she had to do it. You want to make something that is true to how you feel. Because, come on now, it’s terrifying to have a baby. It is terrifying! So why not paint it that way?

ALS: I know your daughter had a child. How does it feel to be a grandmother?

DUMAS: I find it an extreme privilege. I was so scared of being a mother and not knowing how to do it.

ALS: You were always certain you were going to be a mother. Tell me why.

DUMAS: Some people only live for art, and that can make for some really horrible people. A part of me wanted to live only for my art, but I made choices. For a long time, I lived out of my studio and a lot of my friends and fellow artists didn’t have children. But my daughter was very much wanted. It was a big change. I remember one of my notes I wrote from that time: “I’m not one of the boys anymore.” Growing up, it wasn’t that I liked guys very much. But I didn’t really like the women either because of the type of magazines women read, filled with recipes.

ALS: Did becoming a mother change your work or even your way of working?

DUMAS: It didn’t change my interest in the work. But it did change how much time I could spend making it. And it changes your understanding of the family dynamic when you become a mother. For example, you read situations between a shouting child and a mother differently. You realize how difficult it is.

ALS: I’m thinking of your “Great Men” series—Pier Paolo Pasolini, Tennessee Williams, Langston Hughes. They were all intense gay men but they also all had very intense relationships with their mothers. Almost by your act of painting them you are giving them the kind of love that they craved. That’s what I see when I look at that series.

DUMAS: I was so close to my own mother. And it’s interesting because there are a lot of women who feel their mothers didn’t like them that much, or preferred their sons. My father, on the other hand, always treated me well, but he never thought my brothers were manly enough. He never spoke to his two sons intimately in any way.

ALS: You were his favorite. Would you ever put your father in the “Great Men” series?

DUMAS: Yeah, although the series is really supposed to be about men who liked men most.

ALS: For your mythical figures, I get the sense that the painting for you is an act of love.

DUMAS: That’s true. These characters never represent a single person from my life—they are not stand-ins for secret loves, necessarily. But they are built out of aspects and elements of people who I have loved or do love. Even if it’s a figure or emotion that scares me, there’s still something that draws me to it. There was a time when I said most of my work derives from something negative, but I don’t think that’s quite true anymore.

ALS: The motivation of love doesn’t mean there can’t be an element of anger there, too. That’s at least how I feel.

DUMAS: Yes. I don’t think it’s just one thing. It’s a mixture of feelings that come together. It’s like if you really fall in love with someone there is also this fear and danger and worry attached to it. And for painting there is also a liveliness that comes out of the excitement for what you’re doing.

TEETH, 2018.

This article appears in the winter 2019 issue of Interview magazine. Subscribe here.