Mark Flood’s Hateful Years Weren’t Extra Bad

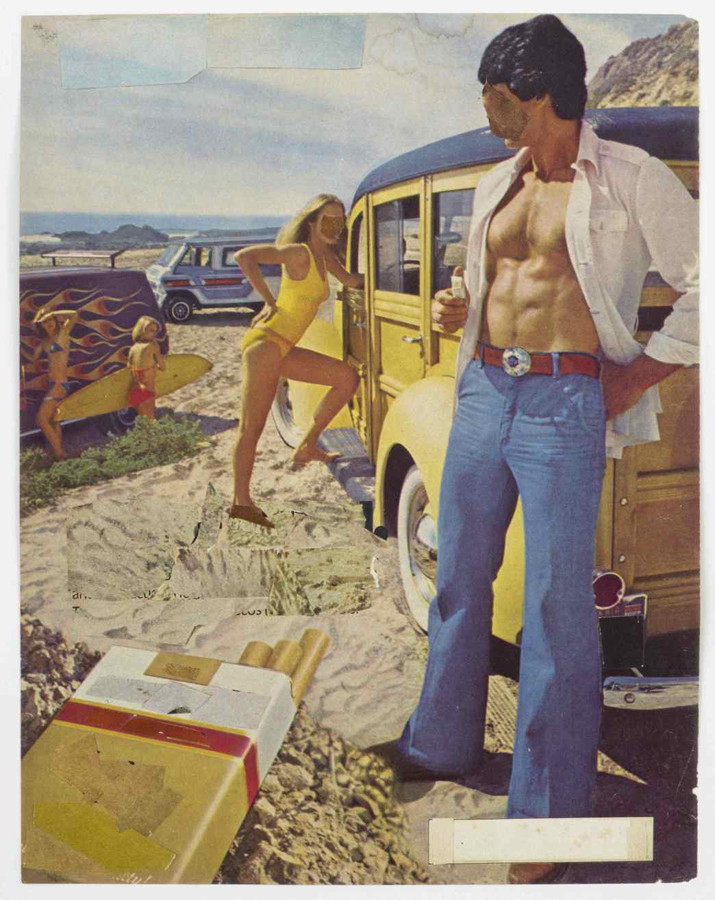

From the title of a survey that emphasizes his work in the 1980s, “The Hateful Years,” you might think that Mark Flood has lingering distaste for the decade. An exhibition of the artist’s output during the era of Reaganomics, hair metal bands, and Gordon Gekko wannabes, Flood’s multi-media works are caustic, often crude ruminations upon the effects of consumerism and capitalism within society. But, as he is quick to point out, the ’80s were really no more a hate-filled time than any other period in human history—that is to say, they were all hate-filled.

Happily delivering his mordant missives from society’s fringes and his native Houston, in recent years Flood has found his works appearing in more gilded locales, including the current exhibition at the posh Upper East Side townhouse-cum-gallery Luxembourg & Dayan. Interview recently spoke to the artist-musician and discussed the cult of celebrity, the place of politics in art, and the value of selling out. Below are excerpts from the conversation.

JOSEPH AKEL: A line in Don DeLillo’s White Noise got me thinking about your art and its apparent interest at the time in the culture industry and celebrity: “Everything we need that is not food or love is here in the tabloid racks.” I’m curious as to how you see the cult of celebrity in America today.

MARK FLOOD: How do I see the cult of celebrity? Well, to me, it’s a continuation of something that has ancient roots. There’s been a long relationship between people and pictures of good-looking individuals who stare into your eyes. People tend to assume that my work is a criticism, but it’s really an attempt to use the power of the forums that are out there in mainstream culture for my own work. In reality, my work has nothing to do with the celebrities, nothing to do with them. It is about us, and why we like pictures of people that stare at us. And it’s the same way today. I think nothing is more boring than an artist who tells you his dumb observations about consumer culture. I consider that the road to ruin. I think art like that is so fucking boring. Don’t even get me started. Yawn.

AKEL: There’s a delicious irony that this interview is for Interview—Andy Warhol was, of course, totally and thoroughly obsessed with celebrity. Receiving more recent mainstream attention, do you feel that you are being absorbed into that culture industry that you speak of? Or have you always been within it, but acting to subvert it?

FLOOD: That’s an interesting question. I don’t mind it. I accept that this is happening. I’m 55; I’d like to place my work in a context that it is accessible to others and that involves a certain degree of cooperation and publicity. As I’ve said in some other interviews, I don’t want to be stubborn to the bitter end, because I’ve seen it cost people dearly. I think there’s something to be said for making sharp turns in life.

AKEL: How do you see your work developing over the last two or three decades?

FLOOD: Importantly, I was entirely inspired by Dave Hickey’s 1993 book, The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty, how ugly art can exist when you have an art bureaucracy providing an audience. But, for an artist wanting to give an audience otherwise, beauty is one way to do that. That was news to me. And it begged the question, what exactly is beauty? So I started studying, looking for technical means, and as soon as I started looking for it, it kind of popped up in front of me.

AKEL: Were the ’80s hateful years?

FLOOD: No, not at all. It’s amused me the writers who have assumed that I was referring to a hateful quality of society in the ’80s. I think that degree of hatefulness is pretty much steady throughout human history. To me, it’s just an amusing sense of self-deprecation, you know—my hateful years. It was entirely personal; it was my personal, hateful years, when I most overtly tried to lash out at society. As I used to say: it was an attempt to burn society down to the ground.

AKEL: Are you more Nero or Plutarch, instigator or commentator?

FLOOD: I would probably have to say Nero. But the one I think of more often is Robespierre. But whatever, I don’t think that’s where an artist’s power lay. I never wished to be a politician, and I despise them. I’ve also wrestled with it over the years, and I deeply dislike propaganda. And all art that is about propaganda, no matter how wonderful it’s cause may be, I think is morally wrong. That’s a major theme of my work. I don’t want to control how people think; I want to show them how they are controlled by pictures. As I’ve said before, it’s not about Sylvester Stallone, it’s not about Barry Manilow—it’s about us.

I not only do not want to comment on politics, I would tell artists, “Don’t be involved in it.” It’s a waste of your time. And, it’s also a reflection of one’s grandiosity to think it’s part of your job to have an opinion on politics. I would point to the always-illuminating example of Duchamp, who’s lived through all of horrors of the 20th century and never said dick about them.

AKEL: This speaks to your aversion of institutions, particularly arts institutions.

FLOOD: Over the years, not so much in the ’80s as in today, I developed an extreme hostility towards the non-profit art organization gulag. I formed the opinion that it’s actually a very sophisticated form of government suppression of creativity, particularly in young people. When I see the younger generation dragged into this and being told to write these statements and take these photos, define your work this way or that way, I think it’s wrong. I think instead of paying any attention to politics, a great project for young artists is to attack and destroy the non-profits of our world. I would add universities to that as well. Because I think that the whole university system is a corrupt, fucked-up mess. I don’t think it has any real relationship to human creativity except to suppress it. And that may sound a little extreme, but here in my little laboratory I get to develop extreme opinions.