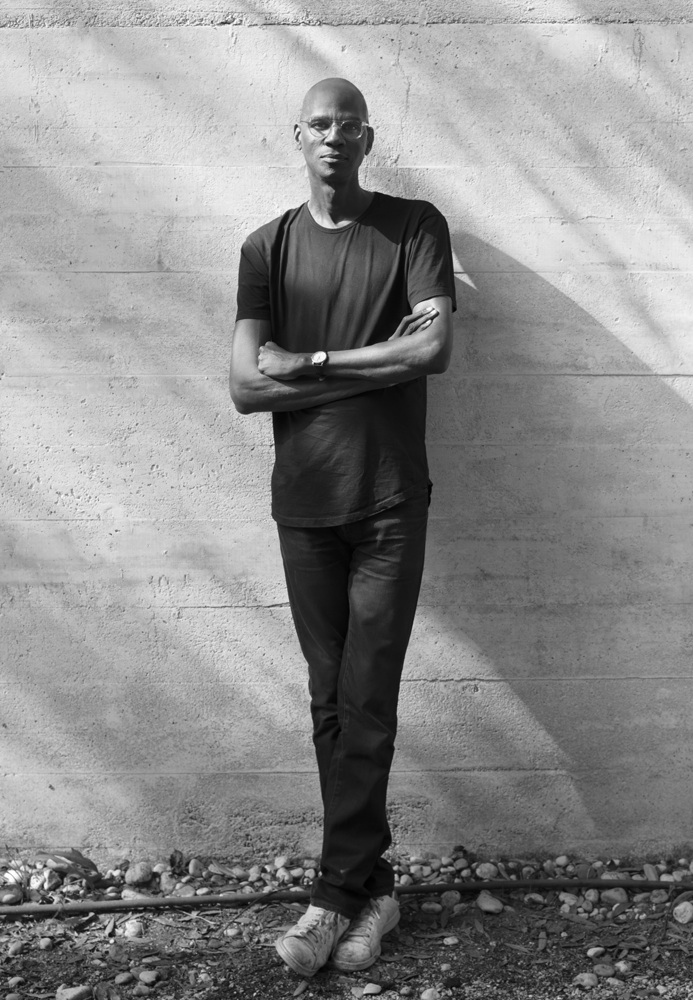

Mark Bradford

Contemporary art has always been better at exposing the contradictions, inequalities, and quiet violence of society than it has at trying to intercede directly to cure them. By and large, artists aren’t expected to serve as social workers or human-rights warriors, and arguably, it’s that very freedom from responsibility that allows for the spontaneity and unexpected provocation endemic to great art. But Mark Bradford is managing to produce stunning, kinetic abstract paintings—a genre that traditionally refutes political expression—while also investing every project with meaningful efforts for social change.

The 55-year-old Los Angeles native grew up working in his mother’s beauty parlor, and some of his earliest paintings were concocted from the supplies he found in her salon. In time, Bradford brilliantly managed to turn cold abstractions into living, telling totems of race, class, and orientation. But he didn’t stop there, scavenging neighborhood ad posters, for example, as the pulp material for another exquisite and deeply layered series. In time, Bradford never produces in a vacuum. Even as he switches mediums, from painting to sculpture to video, there is always the feeling of a man absorbing and reflecting the conditions of a fraught environment—one that is never really “post-racial,” like we had once been promised. His focus on actual, tangible place includes his cofounding of the nonprofit art, activism, and community space Art + Practice in the Leimert Park section of South Los Angeles, with particular attention paid to expanding the horizons of local youth.

This summer, Bradford is representing the United States at the Venice Biennale. Indicative of Bradford’s communal engagement, he’s not only filling the U.S. pavilion with a suite of mostly new work, but also committing to a six-year project with local prison inmates, where the crafts, cosmetics, bags, fruits, vegetables, and herbs they produce are being sold in a Venetian storefront with the proceeds going into prison education and job-training services. Artists aren’t required to help the world, but in light of Bradford’s expansion on the definition of what an artist is and does, perhaps they should. This past April, he was at work on both projects in Venice when he spoke by phone to director Barry Jenkins, fresh off Moonlight‘s memorable and historic Oscar win.

BARRY JENKINS: Is all that hammering from your workshop in Venice?

MARK BRADFORD: Yeah, we’re getting ready. But before we get all into Mark Bradford, let me just give you a congratulations.

JENKINS: [laughs] After six months of nonstop Moonlight talk, I’m much more interested in Mark Bradford. But thank you for the congratulations. It was totally unexpected, and I’m not just talking about the night of the Oscars. I mean the whole run of it.

BRADFORD: Well, the climate was right for the story.

JENKINS: Speaking of climate, I’m amazed that you’ve been asked to go abroad and represent the U.S. psyche, the U.S. consciousness. How does that make you feel?

BRADFORD: It’s been a long process. I was asked during the Obama era—and that was a very different time. For me, it’s been a real emotional roller coaster. It’s like trying to make a movie in the fast lane of the Santa Monica Freeway with the top down. I had to tune out some of what’s been going on to get to the core of the project.

JENKINS: Does the show’s title, “Tomorrow Is Another Day,” go back to the Obama era? Because it perfectly fits the present moment.

BRADFORD: It’s the last line from Gone With the Wind. When I chose it, at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests, it felt like the country was pivoting toward a very dangerous racial path. I was thinking about how race is viewed through Hollywood and how we’re still struggling with many of the tropes in Gone With the Wind today, and how a lot of these images can be very narrowing for our creativity as artists.

JENKINS: Your other project in Venice—Process Collettivo—involves creating a shop for local prison inmates. You’re never shy about including a sense of activism in your artistry. When Mark Bradford makes something, there’s no question it’s about something.

BRADFORD: I don’t have to put a slash after the term artist: artist slash activist, slash, slash, slash … The definition of what it means to be an artist has to be expanded to cover more areas. It’s like being black. I never have a problem with being black. I have a problem with the easy association of what that means to some people. So I just said, “We don’t have to keep changing the name; we just have to demand a multifaceted multiplicity.” I’m just an artist, and what that means to me is I incorporate as much as I choose to incorporate.

JENKINS: I have that Erykah Badu line in my head: “I’m an artist and I’m sensitive about my shit.”

BRADFORD: That’s how I am and how I’ve always looked at the world. I understood what the pavilions were before I came to Venice, and I knew that wasn’t going to be enough for me. I wanted to extend this conversation into something I call urgency. There is urgency with people in crisis. Some communities—often the black community—just live in this urgency.

JENKINS: Your life and practice have been rooted in South Central L.A. I assume in Venice you’re a bit of an outsider.

BRADFORD: They show you what they want you to see and then you have to kind of disappear on your own and start talking to other people. And, come on, there are people in need all over the world. Turn a couple corners and you will run into them if your eyes are looking through the right lens. One person leads you to another person and another person leads you to another person. Eventually, somebody mentioned a prison to me. It turned out that the director is very liberal and forward thinking. It wasn’t just about housing people who have sinned against society.

JENKINS: Can you explain what Process Collettivo is?

BRADFORD: It’s a six-year collaboration with Rio Terà dei Pensieri, a cooperative that works inside prisons in Venice. There are 13 prison cooperatives in Italy that are all self-sustaining, with very little government support. They work with inmates to rehabilitate, to give them job training, and to help them integrate back into the society. Rio Terà is one of them. My hope is that it will get people thinking about supporting prison initiatives not only in Italy, but also as a model for the United States. You know, I grew up in a hair salon. It really was like a cooperative. A person would rent the storefront and then everybody would rent a booth. So they had this kind of cooperative, mercantile, small-funded system, which just feels right to me.

JENKINS: I want to hear about you as a child doing a finger wave.

BRADFORD: Baby, I can hook you up with a finger wave. [Jenkins laughs] My mom was a force. She owned her own business. I had a younger sister, but it was really me and my mom. But it was also a whole community. I lived in an all-black community until I was 11. Then I moved to all-white Santa Monica, but every day we would get in the car and go back to South Central. I was bullied at school, and everything I saw in your movie felt familiar. I’m so glad we’re starting to create language around that experience. Back when I was young, there was no language around it.

JENKINS: Were you into art at that time?

BRADFORD: Nope. All I knew was that an ephemeral butterfly called sissy landed on my shoulder. And one day they said, “Oh, you a sissy.” I didn’t understand what that meant. I was always sensitive. I was always in touch with my feelings. I loved nature. And because of that, I became associated with something that was not good. I felt okay, but people named it something not good.

JENKINS: I spent a lot of time with Tarell Alvin McCraney [writer of the play on which Moonlight is based] talking about naming. He, too, said that before he could name himself, he was named. And there’s no textbook to figure out what the name means.

BRADFORD: And there wasn’t much help around either, because those who could reach out to help you had to be careful or they too might be named. I think you just internalize it. I don’t even know if I internalized sissy, but I sure as hell externalized it!

JENKINS: One thing that fascinates me about your biography is that you didn’t decide to be an artist until deep into adulthood.

BRADFORD: Absolutely. I came from a place where there was creativity, but there were also so many day-to-day factors—like you had to make some money. And I wasn’t scholastic. Although I was smart, by junior high I had fallen through the cracks. I didn’t have that someone who saw something in me. So I was on my way to the nightclub, because that’s where people like me went. But I was always creative. I knew there was something there, but I learned to stay quiet, in my corner. When does one learn one’s voice? When does one learn to stand up and say, “I’m here”? I’m always surprised by people who have that outright because I had to learn to fight and dig my way out of the dark. I had a voice, but it had been knocked down so deep in me.

JENKINS: What were the 1980s like for you? Our biographies dovetail in some ways. For instance, I never really knew my father; I’m not even sure who he was. And then the crack cocaine and HIV/AIDS epidemic of the time played a huge role in shaping my life.

BRADFORD: For me, the ’80s were like that drawing by Botticelli of the nine rings of hell [from Botticelli’s illustrations of Dante’s The Divine Comedy]. Virgil’s ghost descends and there’s sloth, treachery, jealousy—it was a nightmare. Whatever I thought I was going to inherit by being black, I learned from the ’70s, from Good Times and The Jeffersons, with black people owning houses and affirmative action coming to the salon and all the studying for night school. When I was 18, I thought that was the legacy I was going to inherit. And then the ’80s came along. I didn’t even know that black people had such a hard time with homosexuality until then. And here were boys dying of AIDS who really weren’t out of the closet but were completely exposed. It was also the rise of the faith church for me. And it was the rise of crack cocaine, and the rise of foster care, because so many women—some of them my clients—were losing their children to drugs. And then it was the rise of gangs, the Crips and the Bloods, and drive-by shootings. It blew my mind. I had to get out. And here is the thing, Barry: when I was 18 years old, there was no internet and no gay teen nights. Instead, you went to the clubs and talked to grown men and did grown-up things. I knew I wasn’t going to make it, because I knew my self-esteem wasn’t strong enough to say no—like young girls who end up pregnant before they know how to say no to a man. So I grabbed my backpack and wandered. I went to South America, Mexico, Egypt, Europe. I would keep going back with what little money I earned from the hair salon.

JENKINS: It sounds like the hair salon was the one constant in your life. I’m very interested in that transition from growing up in an entirely black world, same as I did, and then moving to Santa Monica and going to a place like Europe.

BRADFORD: I grew up in a boarding house initially with my mom, and that was already kind of communal living. You see, my mom was an orphan by the time she was 3. Her mother died of TB, and my mom was always shifted from relative to relative. I never felt that connected to the idea of a “biological family.” But I like that. One of my sisters is not my biological sister, but she’s my sister to this very day. I became very comfortable with making a family wherever I found it. So Santa Monica wasn’t that jarring. It was white, but it was also the ’70s and everyone was a hippie. Then, by the time I turned 15, Donna Summer came calling my name.

JENKINS: What finally drew you to CalArts, and when did you start listening to the muse of art?

BRADFORD: I think what I realized was that there was a site that I could occupy called a professional artist and it could house all the stuff I’ve always been. I was always creative. I just never named that place—a lot of times, black folks are just doing things, they’re not naming things. [Jenkins laughs] My mom could whip up the hair; my friend could sing real good; my other friend could sew. We were just doing our thing. So when I came back from Europe, I said, “You know what? The only thing that has ever held my interest is making stuff,” and so I just started from the ground up. Got my GPA together, did all the stuff that I was supposed to do. Shit, that was hard. Then I got a scholarship to CalArts, and that was really more about ideas, which was fine with me because I knew how to make things. When I got out, I had plenty of opportunities. I wasn’t exactly sure what my career would look like, but I thought, “Well, I’ll just make one.” And that’s kind of what I did. I’m a Scorpio.

JENKINS: Wait, when is your birthday?

BRADFORD: November 20th.

JENKINS: I’m November 19th.

BRADFORD: Oh, shut up. [laughs]

JENKINS: We’ve got to have a joint party this year.

BRADFORD: I’m going to tell you, as a Scorpio, it’s just about peeling back the layers. And I’m always surprised at myself-there’s a lot under there.

JENKINS: I think black artists working in abstraction is almost a privilege we can’t afford, because when you create work, you feel like people need to be able to read it immediately and that’s inherently not what abstraction is about. How did you come to working in abstract form?

BRADFORD: Well, you just said it. What I was struggling with was developing a space of freedom through my shit. I might have said, “It’s black,” or, “Yes, it comes from South Central, but wait a minute, it’s not going to be didactic. Let me play with it a little bit first.” Often people just want the easy narrative. That’s why, when I saw Moonlight, I realized I had been looking for Moonlight for years, wondering when we were going to have messy, multifaceted black stories. And lo and behold, you showed up.

JENKINS: I had a young brother say to me, “Man, I’ve never seen a scene like that.” He was talking about the scene when the main character wakes up and hears the ocean, which is a dream. And then I realized, “Oh, this brother has never seen a movie where a black character has his dream visualized.”

BRADFORD: They want our story nailed down-easy equations, things that are understood based on historical narratives—and quite frankly we’re much more complex than that and we’ve always been more complex than that. And that’s why I thought, “I’m going to look through the lens of abstraction to pull out my representation, to interrogate a black space through abstraction.”

JENKINS: MmHmm. That is me going to church going, “MmHmm.” [laughs] Now, you use a lot of everyday materials in your work. I read this quote of yours that I love, which is, “If Home Depot doesn’t have it, Mark Bradford doesn’t need it.” Is that intentional?

BRADFORD: It absolutely is intentional because historically abstraction has always belonged to the canon. It’s still the biggest export this country has made: big white men of the 1950s; Jackson Pollock. Then the feminists unpacked it and put it away and said, “Bad.” And that was it, but it’s still in the canon. I said, “Wait a minute, now. We didn’t even get a piece of that pie.” But I didn’t want abstraction that was inward looking; I wanted abstraction that looked out at the social and political landscape. So I took that stuff to my studio and, through alchemy, presented something. My work always has to do with how people occupy this world, and demanding that we have a seat at the table of power. If power is abstraction, which many black men, black women, and people of color have very little voice in, well, then I want to sit at that table. And I’m not going to ask.

JENKINS: Let’s talk about Art + Practice, which really incorporates a lot of the ideas you’ve been working on for so long.

BRADFORD: Often culture gets stuck in static, traditional narratives. Contemporary ideas give culture elasticity, flexibility, which is always a breath of fresh air. But these ideas shouldn’t only be for people who can afford to go to a museum or a symposium in the “better part of town.” For instance, there is nothing wrong with having a contemporary art space next door to a chicken shack or the place where you get your weave done. You know, a lot of times, people in black communities don’t have access to healthy food. It’s the same thing with access to contemporary ideas, access to better health care, and access to better schools. What would have changed had a little Barry or a little Mark walked into a contemporary art space in his own neighborhood?

JENKINS: That was the most beautiful thing about going back home [to Miami] to make Moonlight. Kids would sit at the monitor, they would wear my headset, they would watch me direct. They saw this guy who was from the same place as them telling a story. And I could see in their faces that, right away, it clicked: “Oh, I could do this too.”

BRADFORD: Yes, you can absolutely do something creative and sensitive, and it doesn’t have to do with, “Boys are this and girls are this and men are this.”

JENKINS: I want to ask you about the “Scorched Earth” show you had at the Hammer in 2015—particularly the wall work you did called Finding Barry. That caught my eye, not because of my namesake, but because it was a map with the number of people diagnosed with AIDS in 2009. I was looking at Florida because my mom has been HIV positive for about 25, 30 years now. And when I saw that number, it just struck me down.

BRADFORD: Well, the Hammer has had artists make different works on these walls every few months for years. I was thinking about all of those layers and layers of paint. The artist Barry McGee was one of the first to do one, so that’s why I named it Finding Barry. I wanted to dig down through the layers until I found him, the first person. It’s almost like finding the supposed first person infected with HIV or something. And then I wanted people to see the numbers and understand that this is a real thing and it has to do with real human beings. I wanted people to wonder why the numbers were higher in some parts of the map than others. The AIDS rate is especially high where black people and gay men are. I think people forget what a devastation it was and still is on so many levels. We won’t ever know the full impact of it and the shame that goes along with it.

JENKINS: I went to a friend’s funeral, and his family still wouldn’t acknowledge [his sexuality].

BRADFORD: I did a stand-up routine called Spiderman based on Eddie Murphy in 1983 saying, “No faggots allowed.” Oh my god, I was not having it back in 1983. I remember I was at the amphitheater, and Eddie Murphy got up there and started talking about faggots, and everybody was laughing—I felt like that was the beginning of bullying in a way. I was like, “Are you guys serious? Do you know what’s happening, and you guys are laughing? I’m done.”

JENKINS: How are you looking into the next days, the next months, or the next few years?

BRADFORD: I remind myself that we need to continue to do the things we believe in and be even more vocal about asking people to do more. This might be my Scorpio talking, but everything feels more intense than before. I’ll probably keep doing what I’m doing and shift gears if something comes along. I’m pretty fluid.

JENKINS: I’m trying to do the same. There are a lot of new opportunities that did not exist before.

BRADFORD: We are definitely from the same tribe.

BARRY JENKINS IS THE WRITER-DIRECTOR OF THE FILMS MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY AND MOONLIGHT. MOONLIGHT WON OSCARS FOR BEST PICTURE, BEST ADAPTED SCREENPLAY, AND BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR.