FAMILY

Baltimore Photographer Steven Cuffie Shows Black Women in Their Multitudes

New York Life Gallery, housed in the downtown studio space of the photographer and emerging gallerist Ethan James Green, opened a window onto black womanhood in Baltimore for its inaugural show, Women, a collection of photographs by the late artist Steven Cuffie, who spent his career as a photographer for the city of Baltimore. Cuffie’s extensive body of work has been scrupulously archived and curated by his youngest child, the artist and stylist Marcus Cuffie, who recognized in their father’s intimate portraits a vivid and varied picture of black women in Baltimore, a majority-black city that has been segregated and stereotyped to its residents’ detriment for decades. Both Cuffies, however, are interested in portraying Baltimore and its residents more fully than shows like The Wire, and the curator seeks to understand their father better through the female subjects he so tenderly photographed. As Women opened to considerable fanfare last week at New York Life’s Canal Street location, we spoke to Cuffie about the diversity of experience in Baltimore, what it means to live as—and be raised by—an artist, and how the show functions as a portal into their mother and father’s younger selves.—CLAUDIA BUCCINO

———

CLAUDIA BUCCINO: Can you start by telling me about your dad? What was he like, first as a person, then as a photographer and artist?

MARCUS CUFFIE: My dad was a pretty silent person. My dad was deaf in one ear, and had been since he was a kid, which I think is one reason that he became a photographer. He’s a very silent, often stoic person. These photos come from when he’s in his mid 20s. From that point forward, he really always had a camera with him. He had few words, but if you ever brought up anything about photography, immediately it would pour out. His father was an illustrator during World War II, so he had a background and support being an artist. But he’s one of the only people in his family, besides his father, who really pursued it. His day job was working for Baltimore City as a government photographer, shooting politicians, shooting public events. So he was always always involved in it.

BUCCINO: That means you’re a third generation artist?

CUFFIE: I mean, I’d have to talk to my family. My dad has five brothers. For my grandfather, it was something he did when he was younger, but not once he had 10 kids, or something like that. I’m not sure he could’ve supported 10 kids doing that.

BUCCINO: Maybe back in the day.

CUFFIE: We had a dark room in our basement where my dad would develop the photos himself. It’s interesting, because growing up with him, I had some interest in photography, but it was only after he passed that I tried to understand who he was as an artist. I’m like, “Oh, he really devoted so much of his life to this.” So it’s been really interesting tapping into all this work that came before we were born, before he had these family commitments. I think that’s why the show settled on this topic of women, too, because that is an aspect of the work that I didn’t understand, or couldn’t understand, growing up with him—the relationships he had with these women. So it was really exciting for me to imagine him as this young guy, shooting droves of women around Baltimore, going up to women and getting to know them, to look at the work and see what the connecting lines were: what things and compositions reoccur. Even things like jewelry: there’s images of a moon with flowers that come up repeatedly in the work. So I try to ask myself, “What were my dad’s intentions?” And in doing so, I can imagine the life he led, and the work that resulted.

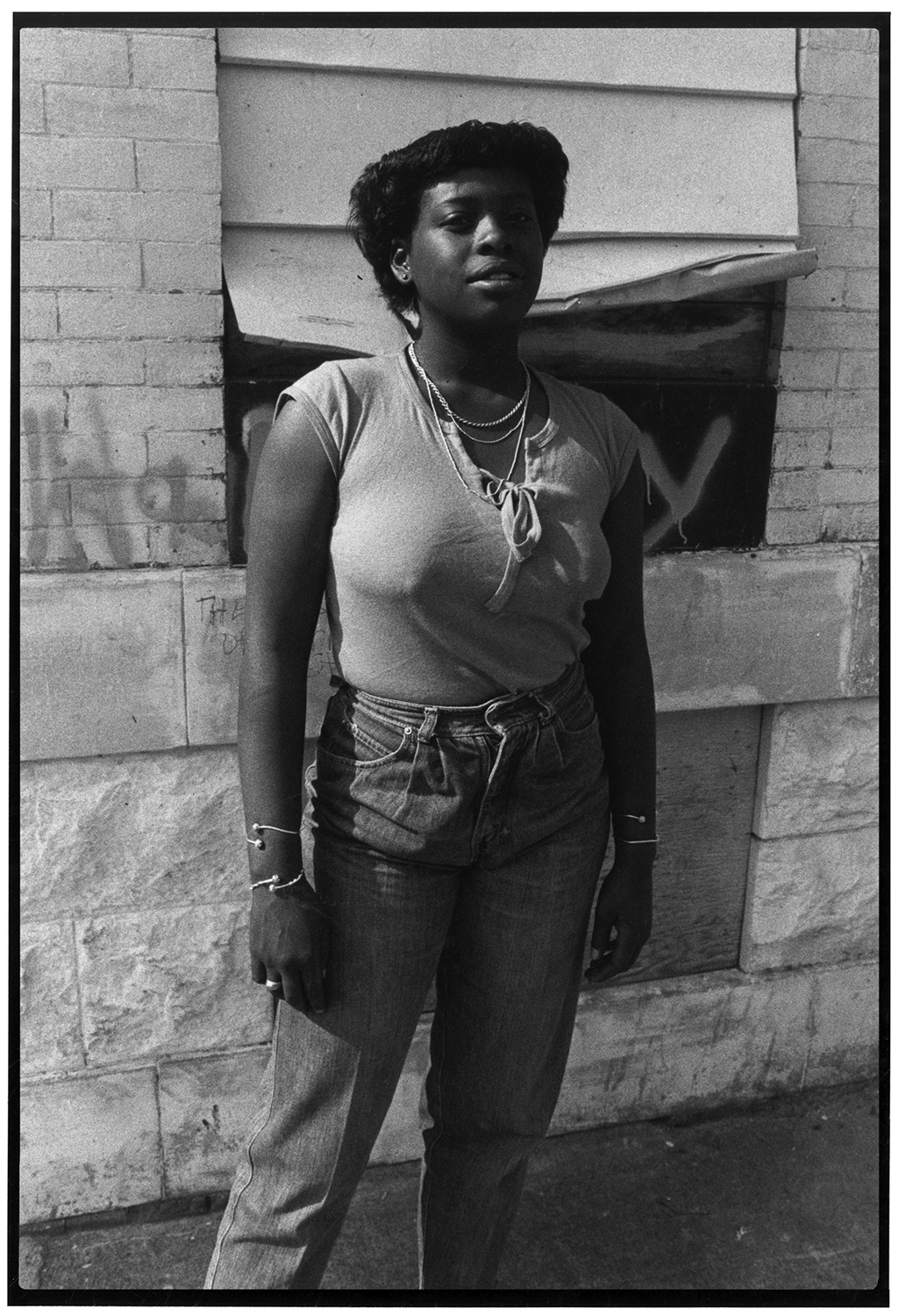

Steven Cuffie, Untitled (Woman Standing on Sidewalk), c. 1970s. © Steven Cuffie Archive, Courtesy New York Life Gallery

BUCCINO: Baltimore was designed to be a segregated city. We can’t talk about it without talking about race. Do you see Baltimore in these photos?

CUFFIE: I see Baltimore in the sense that the photos describe a variety of lives led by black women. For a long time, Baltimore has been a majority black city. Something that’s so interesting about Baltimore is that it’s between the North and South. It’s not a forgotten city, but our understanding of what Baltimore is is almost always through the lens of crime. Obviously, people know things like John Waters, or they know The Wire. Those are the two things that always come up. What I think is nice about the show, and how it speaks to Baltimore, is the way it shows Baltimore in a large scope. I tried to hone in on a variety of images, but also the ones that got at the heart of these women’s personalities. In some, the women weren’t interacting with him as much, so they felt more voyeuristic. I wanted the woman and their personalities at the center of the images. In showing the women together, this world of women with each other, it almost removes my father’s presence. So it’s a balancing act. “How can I make my father present?” But how can I be respectful to the women? There’s a great beauty to them. And they were living in Baltimore, which is such a tumultuous place. So it’s about a man who’s coming to understand his relationship with women: what it’s like to be a woman, and what it’s like to be a black woman.

BUCCINO: You mentioned wanting to understand your dad’s relationship to the subjects in his photos. Did you come to some understanding you didn’t have before you started curating the show?

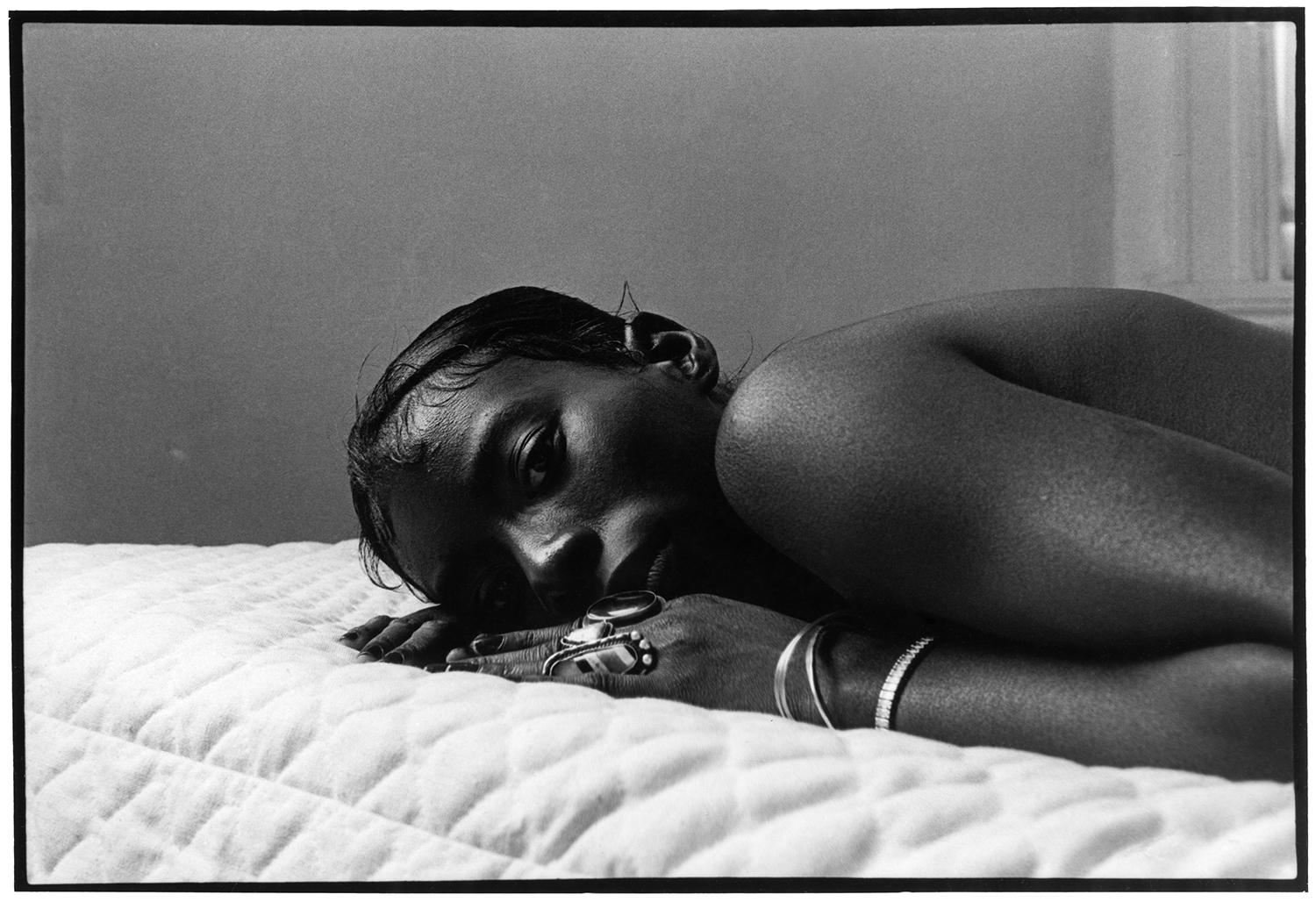

CUFFIE: My dad had a ton of references. And we didn’t see a lot of this work as children. When I was in high school [at the Baltimore School for the Arts], I learned what he read and what he looked at and began to see the influence of certain photographers. My father loved Edward Weston and Anne Brigman, these really early photographers who were doing nudes of women in studio. My father embedded in me this real love for reference, books and history. There weren’t a ton of photographers at that time who were visible and black. I can’t really think of anyone besides Gordon Parks, who was like his hero in a lot of ways, but I can’t think of a ton of black photographers working in the 70s and 80s whose work was known on a large scale.

BUCCINO: And this is the first time your dad’s photos have been shown outside of Baltimore. How do you think he’d feel about showing his work to a wider audience?

CUFFIE: I don’t really know why he didn’t, beside the fact that life got in the way and he had to work and make money. He wasn’t a PR person, he wouldn’t have even had the toolset to begin that process. He did have a certain frustration about not having that kind of reach. But I do think my dad respected and loved Baltimore. And it does make me really happy to be able to show these outside of Baltimore.

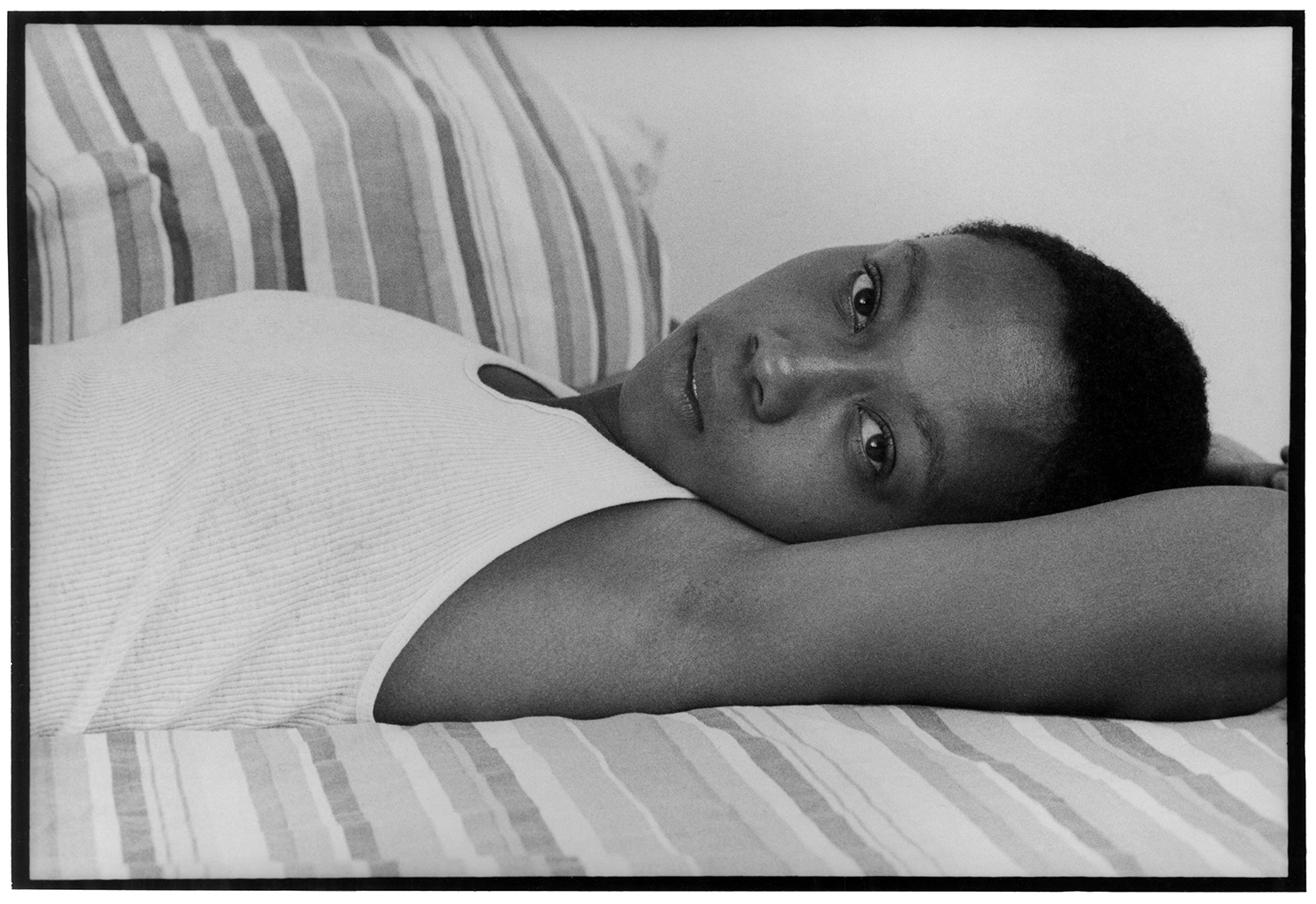

Steven Cuffie, Untitled (Girl Reclining), c. 1970s. © Steven Cuffie Archive, Courtesy New York Life Gallery

BUCCINO: What’s your relationship with the city?

CUFFIE: I mean, you get it. You’re from Baltimore. It’s an interesting place. I grew up there until I was 18. I can’t say I go back often. Baltimore has its charm. But it’s also a weird place. It can be dreary and slow-feeling. A lot of the people I grew up with don’t go back. When I was growing up, I felt like there was a real exodus. Even most of my family has either moved South or North. It just felt like there was a stagnancy in Baltimore. Once I moved to New York, I got tired of these two ideas of Baltimore. Obviously John Waters is very interesting, but he speaks to one particular moment. The Wire is like the other extreme, which only refers to the city’s crime and poverty. But it’s not some set-piece or war zone. It’s a city where people live and enjoy the life they lead. And I think it’s interesting to be able to expand people’s understanding of what the city is, and who its people are. There is a huge variety of people, lives, and neighborhoods, though on a much smaller scale than in New York. And there’s diversity within blackness in Baltimore that isn’t really known.

BUCCINO: I love that about these photos, the representation of the city and its inhabitants. So your dad was basically a lifelong Baltimorean, right?

CUFFIE: He was born in North Carolina, but he moved to Baltimore when he was a kid, at like six or seven. He was there for 60 some years.

BUCCINO: The years that he was in Baltimore, living and working, there was so much historical change in the city. Obviously, he was documenting that for the city. Did he talk to you about his views of the city, or his perspective on the way other people view it?

CUFFIE: When I was in high school, I got to talk to my dad about his work. But some of the intentions or stories behind the images aren’t always present for me because he died when I was 22. So by the time I got to a point where I was like, “Okay, I’ve come into my own as an artist and can have those conversations,” he was already kind of gone. It’s a hard thing to explain how my father related to Baltimore. Blackness was really the center of his life. Baltimore, being a majority-black city, and also being poor and crime-ridden, sort of gives a negative light to aspects of blackness. But for the people who live there, it’s a comfort to them to be in a city where they are the majority, since that’s not the norm. Especially in the 60s and 70s, when there would have been a lot more conflict. By the 80s, the crack epidemic was really awful in Baltimore, as it was in D.C. So that was the beginning of much of the crime that persists even now. I know through some conversations I had with my mother and father that he really tried to teach us about about those dangers. But he also had a “black is beautiful” mindset. There was a love present. He wanted to give us that understanding, so I was always very aware that I was black, and of what being black men in America meant, that it was something to be enjoyed, supported, and loved.

BUCCINO: Right.

CUFFIE: I remember when my sister was younger, my father must have found a vial of crack and he brought it home to show my brothers and sisters to not do it. My mother freaked out. She’s like, “Where do you even get crack to show it to the fucking kids?” I mean, he wasn’t the most subtle in his ways. My mother and father were kind of hippies. In their families, they were the artsy liberal ones. They’ve always had a more radical spirit. They were really big about Kwanzaa, which no one really celebrates. We had all these African masks and prints. Blackness, and our roots as black people, were very important to my dad and his work. That was always super present in his understanding of the city and his understanding of what he was trying to do with his work.

Steven Cuffie, Untitled (Woman in Bed), c. 1970s. © Steven Cuffie Archive, Courtesy New York Life Gallery

BUCCINO: What lessons did you learn from him, specifically about being an artist, especially one not in New York?

CUFFIE: My dad never really showed his work, never got any press or made any money from what he loved to do. But he continued to do it his entire life because he felt a need to do it. It was something he enjoyed doing. My father was hardcore about his craft. If he was going to commit his life to it, he was going to do it in a real way. I’ve gone through periods where I’m like, “it’s really difficult to be an artist, and it’s difficult to come from a place like Baltimore.” My dad was super frugal. He wore the same clothes a lot, mostly just the clothes he shot in. The only things he really spent money on were books and photo stuff. Anything he didn’t put toward his family was put toward his practice. That’s something that’s always been embedded in me. In art school, sometimes you’re with students who have thousands of dollars to spend on art supplies. But being able to make work with the intention, regardless of what you have, is more about your heart and drive than a certain material reality. My father was able to make this work and focus through Baltimore, through his life, because he also didn’t come from money. He came from a pretty lower-middle class family coming from North Carolina. He just wanted to do it.

BUCCINO: Do you feel that same compulsion?

CUFFIE: I’ve always felt this need to make things, to be creative. I feel like I have a right to it. I don’t need any other justification. You don’t always get that confirmation growing up. Not every parent supports their child being an artist, because it’s kind of a foolish endeavor. It’s a risk you take. So much of making art, or working in fashion, or in any kind of industry, is visibility or branding. For people who are outside of New York or the major cities, you feel like, “Do I even have a voice that’s worthwhile?” What my father taught me is that you can build that narrative for yourself wherever you want to, because the intention is inside of you. You don’t need to move to New York when you’re 17 to become an artist.

BUCCINO: So, I was speaking to Ethan about how this show came about. I’m curious what the process of curating it was like for you. There must be so many images.

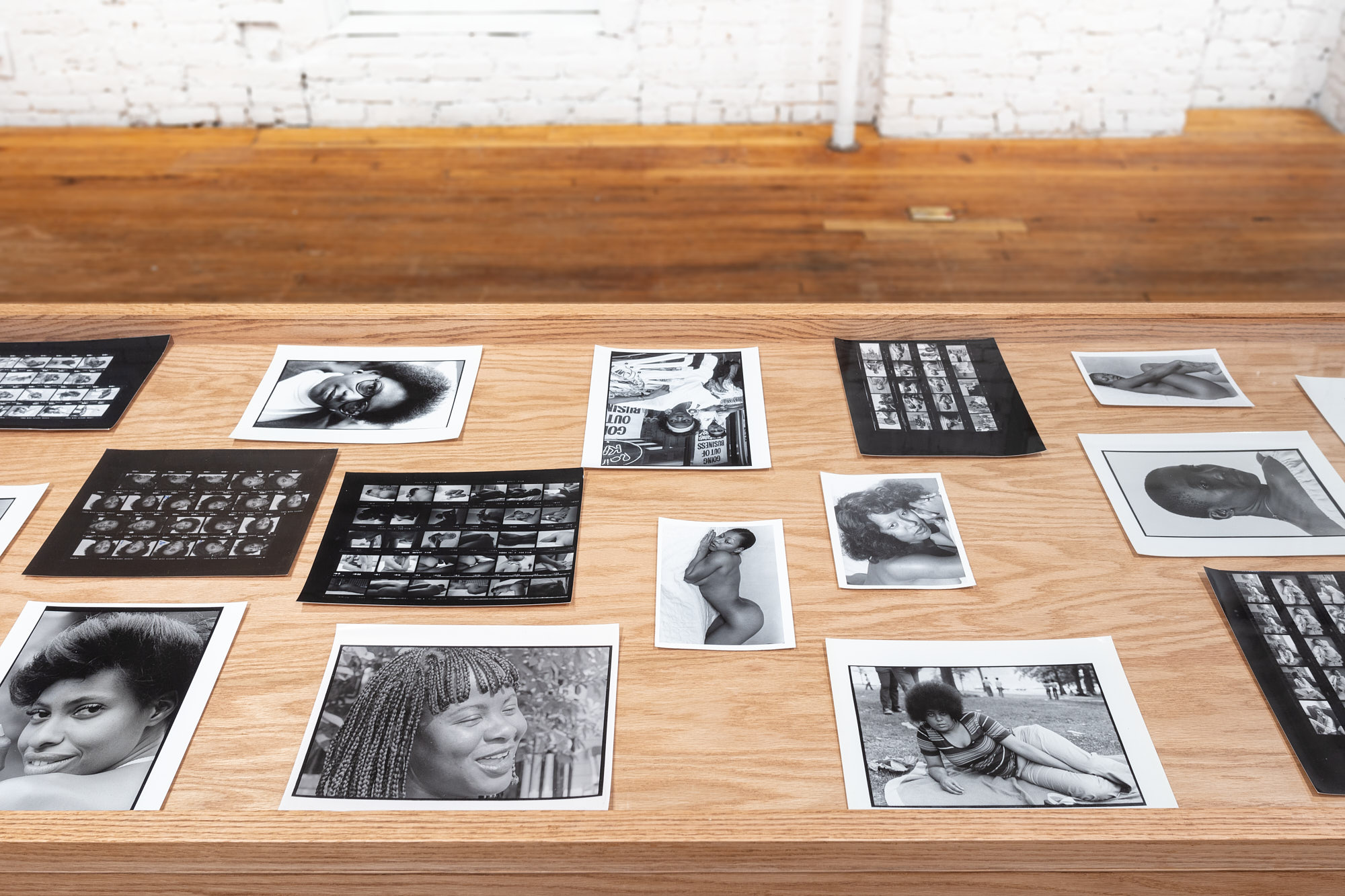

CUFFIE: It started because my sister went down to Baltimore and came back with all these boxes of photos. Between what’s in Ethan’s studio right now and what my sister has, there’s hundreds of photos. And that’s really just the beginning. I told my brother to save all the negatives, so there’s 20 boxes full of negatives, disks, photos that are untouched. It’s quite an endeavor. Working in fashion, I’m used to the speediness of it: you post something, you make something, seasons turn, over and over. What was nice about working on this show was going back to that place I was in in art school, where you’re working on something for a long time and it accrues meaning over time, rather than this quick satisfaction.

BUCCINO: My last request, since we’re surrounded by all the work. Do you have a favorite image?

CUFFIE: It’s probably the image of my mother, which is the third one on the wall there. It was interesting to think about why my father was making certain choices and who he shot, but especially in this picture of my mother. My mother passed when I was 18, so imagining her life before our family came in was so beautiful to me. My mom had a lot of issues surrounding self image and it was very difficult for her to see herself as beautiful. My dad had actually shown some of the images of her nude in an exhibition before any of us were born. She freaked out. But seeing this image now, it felt so beautiful and also vulnerable. I can sense the trust my mother would have felt. That’s beautiful to me, to think that the way my mother and father met was that he was attracted to her as a subject. For her, that could confirm a beauty in herself, which she really needed at that time. She’s also really young. I mean, even last night at the opening, people were like, “There’s a woman who looks a lot like you!” So it’s really nice to feel myself in parallel to her, to think of how I felt when I was 23 or 24, like she is in this photo.