Lucas Samaras

In 1964, Lucas Samaras offered to sell his bedroom, which he had moved into the Green Gallery in New York. While none of the “fine” art sold, the Salvation Army took the furniture. This was the first in many series of innovative performances, unique to the landscape of post-1960s art. Samaras’s work is continuously both highly conceptual and sensually immediate—a riveting combination of body and concept throughout his career in sculpture, painting, performance, and photography.

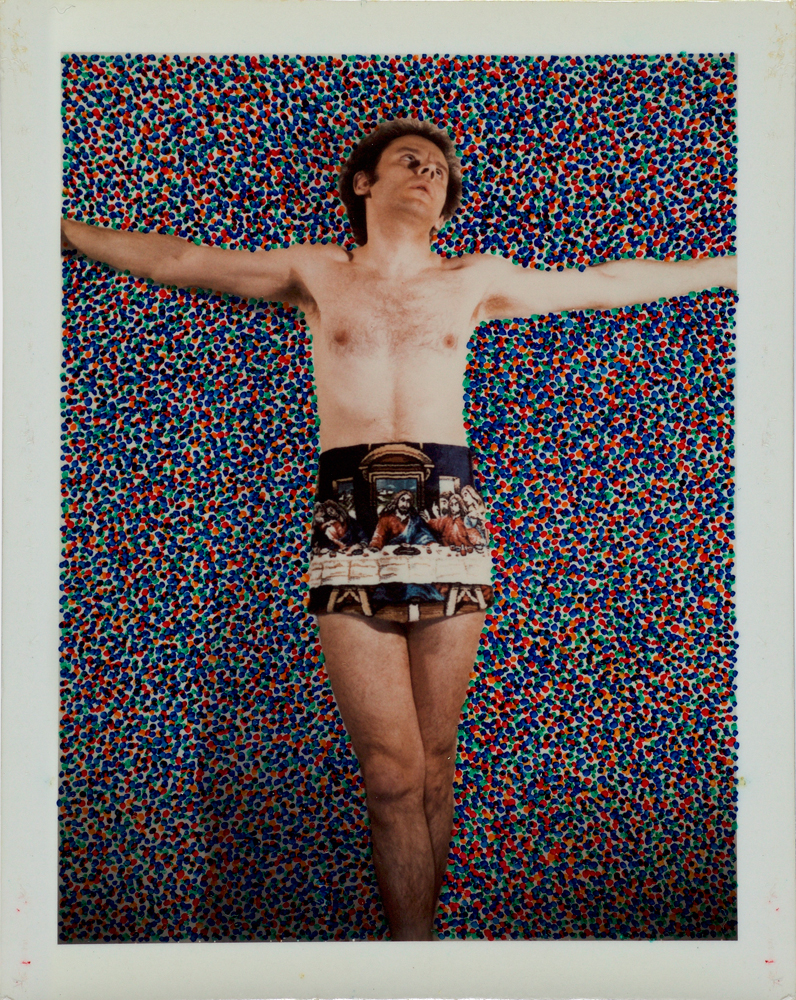

This summer, Craig F. Starr gallery is presenting Samaras’s “AutoPolaroids” from 1969-71, a series that earned the artist a cease-and-desist letter from the eponymous company. The images (never to be called selfies) are as detailed and rigorous as they are comical, simultaneously reflecting his “Auto-Interviews,” a well-known series of work in which he interrogates himself. Samaras, who was born in Kastoria, Greece and immigrated to the United States at age 11, combines self-portraits with a variety of manipulation techniques, including hand-painting. The Polaroid, a symbol of speed and a staid mechanical process, becomes, in Samaras’s hands, a personal object to be manipulated and enlivened.

WILLIAM J. SIMMONS: I’m really interested in how, with Jimmy DeSana, Laurie Simmons, Cindy Sherman, and your work as well, we don’t—

LUCAS SAMARAS: No, you can’t bundle the past together. I’m one of the parents, so you can’t put them and me together. That would be ridiculous, which is fine. I like that position.

SIMMONS: Well, no, but what I’m thinking about is how in the ’80s in photography there was an interest in the surrealist legacy, and I don’t know that we’ve quite put our finger on what exactly that relationship was. How does the surrealist legacy factor in?

SAMARAS: Hang on. You’re not talking about surrealism. You’re talking about traditional photography, which of course you have Robert Frank and so on. Then all of a sudden there are artists who are now photographers, who pick up a camera without going to photography school. It is a totally different way of looking at photography, almost naïve in a way—crude, naïve, but also kind of daring.

SIMMONS: So where do you locate yourself within all of this?

SAMARAS: Well, I’ll give you the dates, and you figure it out.

SIMMONS: I know that you predated much of this conversation. That’s why I’m finding this work to be so interesting. I wonder how to locate your influence. Sometimes it’s good to hear from the source.

SAMARAS: [Artists using photography in the 1980s] found the camera and couldn’t care less about being judged by the old photographers. They were searching for something else. They have different people protecting them or propelling them. Whereas the old guy says, “What the heck is this? Get out of here.” When it comes to my own work, I make it, and hopefully that’s it. Sometimes people don’t see it that day or that year or that decade. It might be possible that the ones who had seen it and like it are dead now. I’m looking back at what I did and how it works. In a sense I’m waiting to see how people will respond. I’m waiting to see how you respond, without asking me to tell you what I think about it, because it is your job to give me an idea of how you go about thinking about this work. And if it’s too absurd then, you know, I’ll kick you out!

SIMMONS: Well, I will try to answer your question. What I am really struck by throughout your work, the photographic and non-photographic, is how you point to many different iterations of the body—your body and a metaphysical body. Maybe what it comes down to is the investment in the tactile, an investment in a direct bodily experience.

SAMARAS: Okay, just stick to the body. I had a show last year called “Album 2” which was shown at the Pace Gallery. I have albums of my family and myself, and then I say, “Let me take those photographs and blend them with an art landscape.” So I went back to beginning, age zero, and I was fascinated to see how I responded to photography from childhood to 1969, when I bought a Polaroid. That’s where my journey began, not as an investigation, but as a presentation of myself. I’ll show you a bit of that progression from that show. Here’s a photograph from around 1947 of my family. Here is everybody, and here’s me, looking at the camera a different way than my family is performing.

SIMMONS: You look like you have a self-knowledge of the photo.

SAMARAS: I’m like a little demon. Now here’s another one, from maybe a year later. All these relatives are to one side, and I’m on the other side. Already I’m having some discourse with the camera without even knowing that I’m doing it, or maybe I do, who knows? So now we come to another one. Here I am again.

SIMMONS: You’re looking in a different direction. It’s almost as if you’re aware of the outside of the frame.

SAMARAS: Yeah, there’s something unusual. If you were smart enough you could find out what it is, but I’m not smart enough. So after many occasions of that, I come to a more mature way of showing my body. I bought a camera when I was in high school, a Voigtländer. It was terrible, so I was very disappointed; I took some pictures, but they were horrible. Then a couple of years later, around 1966, I asked a relative to take pictures of me when I was living in a dump up on 77th Street. So I took off my clothes and I got in the tub—the tub was in the kitchen. I just liked it. I was having my naked body photographed in a context that I used every day. Then I put the cover on the tub and had lunch on it. That was the start of being more interested in doing a photo myself instead of somebody else doing it, which is why in 1969 I bought a Polaroid. I loved it because the Polaroid has these wonderful blacks and wonderful whites. I was seduced by the camera.

SIMMONS: It seems like you were harnessing or taking charge of something that might have already been inside of you or in your brain. There’s something about owning the image.

SAMARAS: The thrill was that the camera itself was fantastic. It gave me, without even asking, the right blacks and the right whites. Then it was up to me to put the camera here, to put it there, put it wherever, and pose. I could do anything and say, “Well, that’s stupid but it’s interesting.” It’s almost as if you have yourself and say, “Okay, do something. Interest me. Excite me,” and I’m going to excite you with something ridiculous or semi-tragic or humorous. Then I started showing them to people. Most of them were horrified—you know, whenever there’s nudity. It was a presentation of something different.

SIMMONS: You’re describing the camera almost as an extension of your body and not as a tool or some sort of psychic extension.

SAMARAS: Yeah, the brains of the magazines at that time were not that ready to accept it. Except Jean Lipman, who published 16 pages of them in Art in America in November 1970.

SIMMONS: This suggests a relationship between your photographs and your sculptures. Your work is an extension of your body, even if it’s not a physical representation of your body. I’m thinking of your use of pins, for instance.

SAMARAS: Most of the people from my town were involved in the fur business. I use pins, which are like fur, but you can touch fur and you cannot touch pins. However, if you’re careful you can; you can scoop a whole bunch of them in your hands and then you say, “What objects do you want to hold?” You just have to deal with the surface. But as to how it relates to my body, well, what do you think?

SIMMONS: I’m thinking of Eva Hesse. She re-added the body to the formless space that was pioneered by the minimalists.

SAMARAS: But why are you referring to people who came in five or seven years after me?

SIMMONS: Just as an example. She made the discourse on minimalism aware that there was in fact a body, that it wasn’t a universal amorphous, conceptual realm, that it was a tactile and corporeal space, even if it’s a minimal form.

SAMARAS: So what are you saying?

SIMMONS: It seems to me that your work points to the sort of embodiment of space which I think connects to what you were talking about with the photograph too, that even in your childhood you were aware of space and your body’s relationship to space.

SAMARAS: In 1964, when I presented my bedroom, I wanted a space where you could go inside the artwork and could not escape from it. And it had to be real, it had to be “it.” So if I said bedroom, I meant literally my bedroom with my bed, my garbage can. The other thing that is important to me is skin. Skin has hair. It also has pimples.

SIMMONS: It’s also the connection between the inside and the outside, right? Maybe it’s the Fluxus understanding of space.

SAMARAS: Oh, you just mentioned the word that I don’t want to hear again.

SIMMONS: I’d like to hear why you don’t want to hear that word. But I’m also thinking about John Cage’s 4’33.

SAMARAS: Cage begins with a completely different thing, and that is questioning everything, you know, screw Beethoven, and all that. Using a broom on The Greats of the Past is good for a time, but then you need to throw the broom out and engage beauty, technical beauty. I wanted beauty. The Fluxus brutes, they could care less about beauty. When you go to a museum and you see the Renaissance or Impressionism, you’re thrilled by that technical goings on. Getting an apple and just sticking it somewhere does not thrill me. Just stick it up your ass and get the fuck out of here.

SIMMONS: So it can’t all be about concept. The photograph for you is not a way to document—

SAMARAS: No, documentation is terrific, but it has to transcend ordinariness.

“LUCAS SAMARAS: AUTOPOLAROIDS, 1969-71” WILL BE ON VIEW AT CRAIG F. STARR GALLERY UNTIL AUGUST 12, 2016.