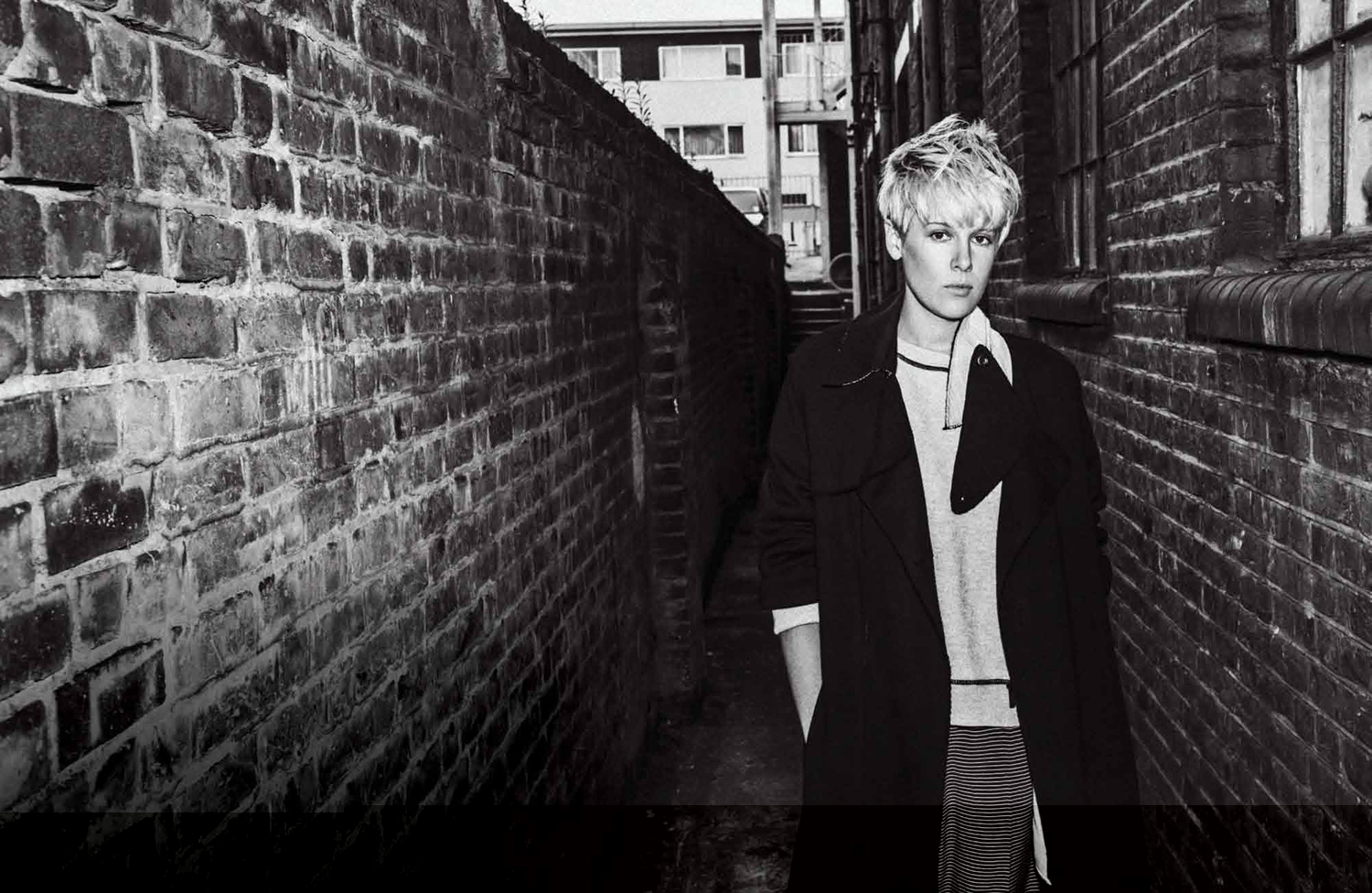

Helen Marten

One of the most compelling artists to emerge out of London in the past few years is 26-year-old sculptor and video artist Helen Marten. She had recently moved her studio into a space in a freshly converted theater in Dalston, but she has yet to unpack, mainly because her most recent work, the 29-minute CGI animation film Evian Disease, now showing at the Palais de Toyko in Paris, required none of her usual hands-on sculptural assemblage-at least not in the physical sphere. Evian Disease, with its hyper-real imagistic juxtapositions of nature and commodity inhabiting a flattened plane, “reeks of dishonesty,” according to the artist. “There is nothing to touch, no smell, just this weird rubbery shell that at the same time is both materially dead and data-osmotic. In some ways, it is more code than text—the gender has been stripped out, and with that, a sense of the weight.” There is a startling weightlessness to much of Marten’s work, including her highly packed amalgams of objects, which seem neither improvisatory and unintentional nor permanent. Take the disarming mutant vacation sculpture No juice about it (2011): The piece consists of a grid of bamboo fencing, which is actually made of steel, on which a patchwork quilt and a lei are strung, and in front of which a clay-looking pineapple, actually fashioned from cast aluminum, is coyly humanized by wearing a pair of Oakley sunglasses. While the materials in Marten’s sculptures may look found, they are almost entirely created from scratch by the artist. The result strikes, in her words, “a balance between the seamless, coldness of fabrication, and then a kind of assertive crappiness.” Marten’s object ecosystems have the visual wit of Sarah Lucas or Robert Gober—or Martin Kippenberger, one of her influences—but they hold a deeper tension in terms of the presence of the artist’s hand versus the sleek seduction of the surface. Marten’s pieces have roved from incorporating wall paper to cell phones, industrial hardware, neon light, and, of course, animation-perhaps the ultimate art form for the convergence of the unreal with the almost human. The occasional clunkiness only forces the viewer to negotiate her pileups more carefully. “I suppose I’m trying to upset the expected rhythms of daily circumstance,” she says, “exploring what it means to be a tribal human preoccupied with the status of toothpaste, the floppiness of pasta, eroticism of rubbish, or tedium of hair.”

PHOTO: HELEN MARTEN IN LONDON, OCTOBER 2012. COAT: EMPORIO ARMANI. SWEATSHIRT: TOPSHOP. PANTS: MARTEN’S OWN.