AI

“Why Should Artists Have to Be Good Citizens?”: Laurie Simmons, in Conversation With David Salle

Photo courtesy of Laurie Simmons.

In her new exhibition at 56 Henry, DEEP PHOTOS / IN THE BEGINNING, Laurie Simmons breaks away from photography as her primary medium, opting instead to transfigure her lifelong fascination with dolls and toys into wall-mounted scenes of domestic and public life. Simmons began this project during the pandemic after assessing the countless props on her shelves and being told repeatedly that she was in a “high-risk” age group, an edict that accounts for the “dire” nature, to quote her friend and fellow artist David Salle, of some of the scenes depicted. Salle, too, dispenses with some of his own artistic conventions in his show New Pastorals, which opened at Gladstone last week. Here, the painter uses AI for the first time, a thorny practice with which Simmons has long been well-acquainted. Earlier this month, the two artists got together to talk about man, machine, the contemporary art world, and animated cunnilingus.—EMILY SANDSTROM

———

LAURIE SIMMONS: I’m really excited to see the new paintings in person.

DAVID SALLE: Thank you. It’s a big change, but at the same time it feels very continuous. There’s certain things I’ve been wanting to do for a long time and now they’re coming out.

SIMMONS: I felt like these paintings are a little bit looser and a little bit sexier. I think AI is a great collaborator for you.

SALLE: These pictures have something, some quality that I’ve been working up to for a long time. The AI was a great accelerator. It probably saved me years. We all want to get outside of what we know, our habitual ways of structuring a picture. It turns out to be really hard to use distortion in a painting. The machine can do it without any qualms. It doesn’t have any sense of transgression; it’s free of any constraints, like good taste or anatomy.

Installation view, David Salle, New Pastorals, Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2024. © David Salle/Artists Rights. Society (ARS), NY, Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

SIMMONS: You and I both chose to work with AI, but in my case, I haven’t trained a model. Immediately the programs responded to my prompts and generated images that are continuous with my work, but also something I’d never seen before. It is such a good collaborator. But I do a lot of work by hand to change the images AI gives me, and the show I have up right now has no AI in it at all, it’s sculpture that I built out of past props, like my own past work is my collaborator. I’ve always responded to the free-associative aspect of your work, and I’m imagining the brain that pulled this variety of images together. And if AI takes you to the next place, great. It seems to have done exactly that. But you and I have always relied on something else to help us make our work. It’s not like you and the paintbrush and a white canvas have ever been alone in a room together. There’s always been a tool.

SALLE: I think it’s a matter of temperament. I’m more of a responder than an initiator. Maybe I should say I’m a ‘first responder’. I’ve gotten over any self-reproach about it. I’m often responding to something I’ve seen, or found. A big part of my day is looking for things to react to. AI is just the next level in terms of having something to respond to. What is the “something else” in your work?

SIMMONS: Well, the “something else” was picking up a camera in the first place, when my education was based in painting and sculpture. My first pictures I ever made were placing dolls in front of other people’s pictures. When I started, most people were out on the street with their cameras, and studio-based set-ups like mine were a questionable idea. But I needed source material. I looked for backgrounds and ended up photographing them. It was pretty direct. I’m using AI in the same way. It gives me source material. And my box constructions at 56 Henry take my own source material from the past decades. I’m making objects from myself, from my own work.

SALLE: I wonder if you also have to deal with this: people will tell me, not in so many words, that my work is over-full and over-complicated. The complaint is that the images are random, a word which makes me bristle just a little bit. When confronted with a sequence of images in which the connective glue is not illuminated by flashing lights, people will say that it’s random, which implies that there’s no agency.

SIMMONS: They say random, I say pastiche. When I put things together, I really go for trying to make everything perfect. There are inherent scale and perspective discrepancies in my work, so nothing could ever be perfect, but it’s in me to make everything fit together. I’m painting and embroidering AI images by hand in the same way—the collaborator gives me something that is off, it will always be off, and I need to make it fit into a new composition. I’m compelled to correct the mistakes that I see the AI making. But let’s not devolve into complaining, which most artists love to do.

SALLE: I’m not complaining. I’m just observing. One makes one’s work and you’re having a dialogue with yourself in a certain way, and then other people see it and they react completely differently. It’s nothing to bemoan; I’m celebrating the fact that anyone looks at it at all. But I have long felt that it was a terrible failing that I cannot paint from imagination, and I’m so incredibly envious of people who can. I can only draw or paint what’s in front of me. I need visual stimuli in order to have somebody to react to, whether it’s AI or just looking through a magazine. I realized at a certain point in my 20s that I spend more time looking at pictures in magazines than looking at things in the world. And that was useful when it came time to paint something. I’m a slave to appearances in a way, which is the worst thing you could say about someone, but there it is. What about you?

SIMMONS: I was one of those kids that showed up at kindergarten identifying myself as an artist, but when I think back on it, I couldn’t draw that well. We have some of your drawings, and I always assumed that you can really draw. I don’t know if that’s true.

SALLE: I can sort of draw, but only what I’m looking at. The repertoire of what I can draw from my imagination is extremely limited.

Installation view, David Salle, New Pastorals, Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2024. © David Salle/Artists Rights. Society (ARS), NY, Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

SIMMONS: Right. Well, I can draw an umbrella, an olive, and a skirt. I was showing Carroll [Dunham] the new paintings, and I was so excited about the skirts because it’s something that I draw. I love plaid ones, polka-dot ones.

SALLE: I thought you might respond to them. Not because of gender issues, although that could be part of it, but a skirt is a great form. They’re really interesting things to paint because they take the form of the wearer. And they move, so they imply a great deal of motion, and especially if they’re plaid, and you leave part of the pattern open to see through something as if it were on the other side. They have the aspect of stained-glass windows.

SIMMONS: In 1998 I made a series called Underneath the Skirt, and at the time, Metro Pictures didn’t want to show it. Basically it was these women in skirts sitting with their legs apart or with their knees up to reveal the underside of their skirt, where their panties would be. Then there was a little world that existed, which came from this memory of crawling around under the table at family holidays and knowing how verboten it was to look up women’s skirts. But this thing about skirts, it’s what’s underneath in so many ways, which brings me to this painting that Carroll and I own of yours that I look at every day because it’s outside my bedroom. You know the painting I’m talking about.

SALLE: I think so, yes.

SIMMONS: If you don’t want me to talk about this, it’s fine, but one of the reasons we were able to get that painting is because this subject matter didn’t appeal to everyone. Basically, it’s the seven dwarfs going under Snow White’s skirt. And, for the sake of a magazine, do we say “performing cunnilingus” or “going down on Snow White?” You can take your choice.

SALLE: I think “going down on Snow White” has a nice ring to it.

SIMMONS: It’s really such a phenomenal painting. I love Walt Disney, I love fairy tales, I love skirts.

Installation view of Deep Photos. Courtesy of the artist and 56 HENRY, New York.

SALLE: Skirts have an inside and outside and they look very different depending on who’s wearing them. The transformation of form—how things trade places—is one of my subjects, and the skirt is a vehicle for that idea. Sometimes it’s a bell, or a funnel, or a sail. Or a window. Sometimes a skirt is just a skirt.

SIMMONS: And sometimes it’s so much more than just a skirt. You saw in my sculpture, The First Week of School, that six identical little girl dummies, who are meant to be me, are dressed in proper school dresses. They’re the party dresses I had when I was that age. Appearances mattered, and we were terrified of wearing the same thing to school two days in a row. Now, I think about what a privilege it was to wear something different every day of the week. But at the time, the social and economic pressure was enormous, especially as first-generation Americans.

SALLE: Yeah. Fashion has always been a great subject for art. It’s not exactly news. What made many of the great painters was how they treated clothes. It took much more attention to paint a satin dress with a million bows on it than it did to paint the portrait of the person wearing it. I recognized that in the dummies, the clothes they’re wearing. I love those pieces because the uncanny as the operating principle couldn’t be more real and alive when you see a dummy with custom-made clothes.

SIMMONS: Absolutely. I wanted to get back to the AI stuff. Obviously, there’s as many articles in the paper right now about AI as there are about Taylor Swift. “Is it the end of the world? Is it not the end of the world?” It’s nonstop. But for me, it’s a tool like Photoshop or anything we’ve ever used.

SALLE: Right, of course. Put it this way, everyone’s AI experience is going to be different. AI is essentially a scanning device. It scans for similarity and dissimilarity, which, guess what? Is exactly what the human eye brain does. And the way composition works in painting essentially is as your eye scans the rectangle, you note this red shape over here connects visually to this red shape down here in the other corner. If you do that nine million times, you have a sense of what the painting is. But the machine does it really, really fast, and then it links all the similarities together. I don’t even care how it works. It doesn’t interest me really. But I can still hear John Baldessari’s voice in my ear from 1971 talking about the portable video camera, which was then brand new. People were arguing, “Is it art?” And, “That can’t be art. That’s a video camera.” And John said, “It’s literally just another pencil in your paint box. Either you make something interesting with it or you don’t.”

SIMMONS: Exactly.

SALLE: There’s no a priori good or bad. I’m not a tech person, so I could be naive in the sense that tomorrow this will have taken over the world and we’ll all regret it, but I don’t think so.

SIMMONS: Well, the part of the tool that we’re using, we’re not responsible for the entire world. But we can influence the conversation of how AI uses resources. As people using it, we can say, these issues need solutions.

SALLE: Oh yes, as artists, we’re responsible for everything.

SIMMONS: [Laughs] I know.

SALLE: I mean, why should artists have to be good citizens?

SIMMONS: Oh my god. If we start to have that conversation, we’re off and away.

SALLE: But I have observed that so much of the work that’s produced using AI, the reason so much of it looks generic and therefore boring is because it is generic. It’s literally a product of averaging billions of images downloaded from the internet. People use linguistic prompts, “Make something in the style of X,” which is fine. It’s a great parlor trick, but it is not very interesting as art. So what I did was quite the opposite: I started with a blank slate, and I trained the machine on very specific painting-101 stuff, and then further trained it on very specific images of mine. Anyone could do the same thing, but it’s a very different approach. I’ve been on enough panels with people who invented the bloody machine or who have raised hundreds of millions of dollars to promote their version of it to know that precisely the thing that they’re most proud of, the fact that this thing has downloaded billions of images, is precisely the thing that makes it fail.

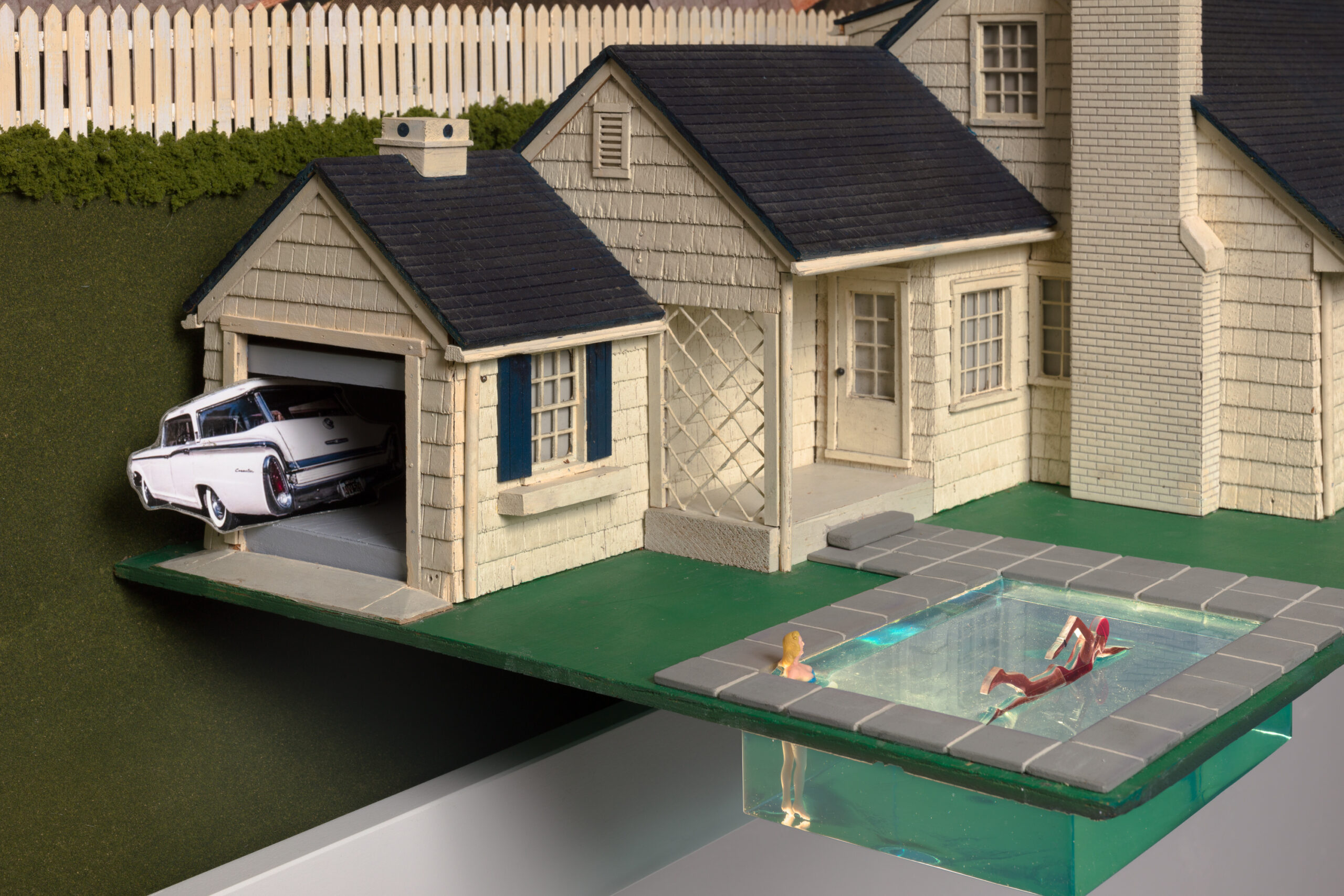

Detail from Deep Photos (White House Green Lawn/Swimming Pool), 2024. Metal, wood, inkjet print, resin, plastic, paper, acrylic paint, paper, plexiglass. 40 × 60 × 20.25 in. 101.6 × 152.4 × 51.4 cm.

SIMMONS: The datasets are biased. The images can sometimes be shocking, in terms of their misogyny and racism. There are other artists who are making interesting work about this very bias. In my studio, I’m getting exactly the images that I want, that are seamless and virtual continuations of the language that I’ve been speaking for 40 years. It simply looks like my work. And as I mentioned before, I did not have to train a model, I just gave it prompts. I think it’s interesting that we’re both using it, but you’re training a machine, you’re training a program, and I’m not. And we’re still managing to use the tool to get something.

SALLE: Of course, you found your own way to extract what you wanted from it. As I said, everyone’s AI will be different. The funny thing about painting or art making generally is that it’s amazing how much one is always oneself, even when you’re using a tool which has no idea what it’s doing, and ergo, could do anything. We’re all tethered to our sensibilities, for better or worse.

SIMMONS: But I think that’s why I fell in love with it quickly, because I was seeing things that I could imagine calling my own. But I have a question for you: How do you feel having a show opening in the fall of 2024?

SALLE: You mean, as opposed to any other year, any other time?

SIMMONS: It’s an open question. I’m just taking your temperature.

SALLE: I never asked myself that question. I have to think about it.

SIMMONS: You’re good at talking about how the art world has changed. That’s a conversation we often have, so that’s why I’m asking you.

SALLE: Oh, of course it’s changed. I don’t really have a very clear picture of the art world or even the desire to have one. I just tend to think about it as, “Well, I got the job done. I finished the paintings, and the show is scheduled to open, blah, blah, blah.” Then it’s on to the next thing.

SIMMONS: Well, we know how to get the job done, but the thing that we’ve talked about in the past is that the art world used to be knowable. We understood it in a very broad way, and now it’s unknowable.

SALLE: Yes. I’ll give you an example. I won’t mention his name, but there’s a very well-established and highly regarded younger painter who had a show last year. I went to see it and I wrote to him afterwards about how much I liked it. He was so appreciative that I wrote because he said he felt like there had been no echo coming back whatsoever. Not only was it not reviewed, but no one said a word. It was like it never happened. I thought, “Well, there’s something wrong with this picture.” Because the reason that we all live in New York is so that you can gauge the impact you’re having. It’s an individual endeavor, but once the work is made, it’s a joint project.

SIMMONS: It’s dialogue, too.

SALLE: Yes. If you’re speaking to others, but no one’s speaking to you, it’s a weird feeling.

SIMMONS: But I feel like that happened to me with shows in the ’90s or the ’80s, even. You would put up some shows, and you would be at your opening, and you’d feel like everybody’s here, but they’re talking about the fact that it’s snowing outside or the after-party. You could have a show and then experience a deafening silence along with no sales and no reviews. That was always the trifecta, and you just have to wake up and live another day. I feel like it’s not a new thing.

SALLE: No, it’s not. I’ll give you another counter-example that forms my image of the way the art world used to be. This would’ve been sometime in the late ’70s, or very early ’80s. I was in the Mickey Ruskin Bar having a pleasant conversation, and someone came in who had just had a show open in SoHo. He must have come in to take a few bows, clearly, because everyone was loving what he was doing. He says hello to us, and someone turns to him and says, in a very even voice, “I’m really tired of that feeling of hot air coming out from behind your paintings all the time.” And I felt so energized to be let in on this secret that it mattered enough to have a strong opinion about the work. Today, no one would even know how to have an opinion about the art, they would just want to know how well it sold. And that’s the difference.

Deep Photos (Cowboy Town), 2021. Plywood, teak, pine, plastic, paper, synthetic grass, metal, hot glue, acrylic paint, fabric, stone, glass. 60 × 40 × 8.75 in. 152.4 × 101.6 × 22.2 cm.

SIMMONS: I don’t know. I have more faith and confidence in younger artists, and I know a lot of them they’re still thinking about the work. There’s definitely a lot of focus on sales, and it’s definitely harder to stay alive. But I think that people, especially young artists, really care about the art.

SALLE: Good. I guess I don’t know that many young artists. I didn’t even tell you how much I love these wall pieces, these things of 56 Henry. There’s something dire in the association with these floor plans. I guess it’s associated with a crime scene or something?

SIMMONS: Well, I started them at the beginning of the pandemic when everyone was telling us, especially given our age, that we were in a very high-risk group and would probably die. I just started looking at my shelves of props and things that I thought that I would photograph again. I thought, “These need to go away, but I can’t give them away.” So, I started recycling them into these boxes using the visual space that I’d learned through the camera, and from looking at paintings all these years. The dire part was this strong feeling about death being all around me. I never think of them as crime scenes because there’s never a narrative in my work.

SALLE: I don’t know why it came to me as a crime scene, but why else would one look at a floor plan with furniture except to pinpoint where the murder happened?

SIMMONS: I would think the reason that they would appeal to you is because each room has a view from many different angles.

SALLE: Yes. Essentially, it’s a deconstructed cubist sense of space. Maybe that contributed to the sense of direness. I find them very compelling. There’s something inherently compelling about miniaturization, but it’s way more than that. Maybe it’s the mixed spatial points of view.

SIMMONS: Maybe they’re a little bit random, too.

SALLE: Oh, that word again!