ART BASEL

Laurie Simmons and Walter Robinson Enter the Big-Breasted World of A.I. Art

Laurie Simmons, photographed by Danielle Bartholomew.

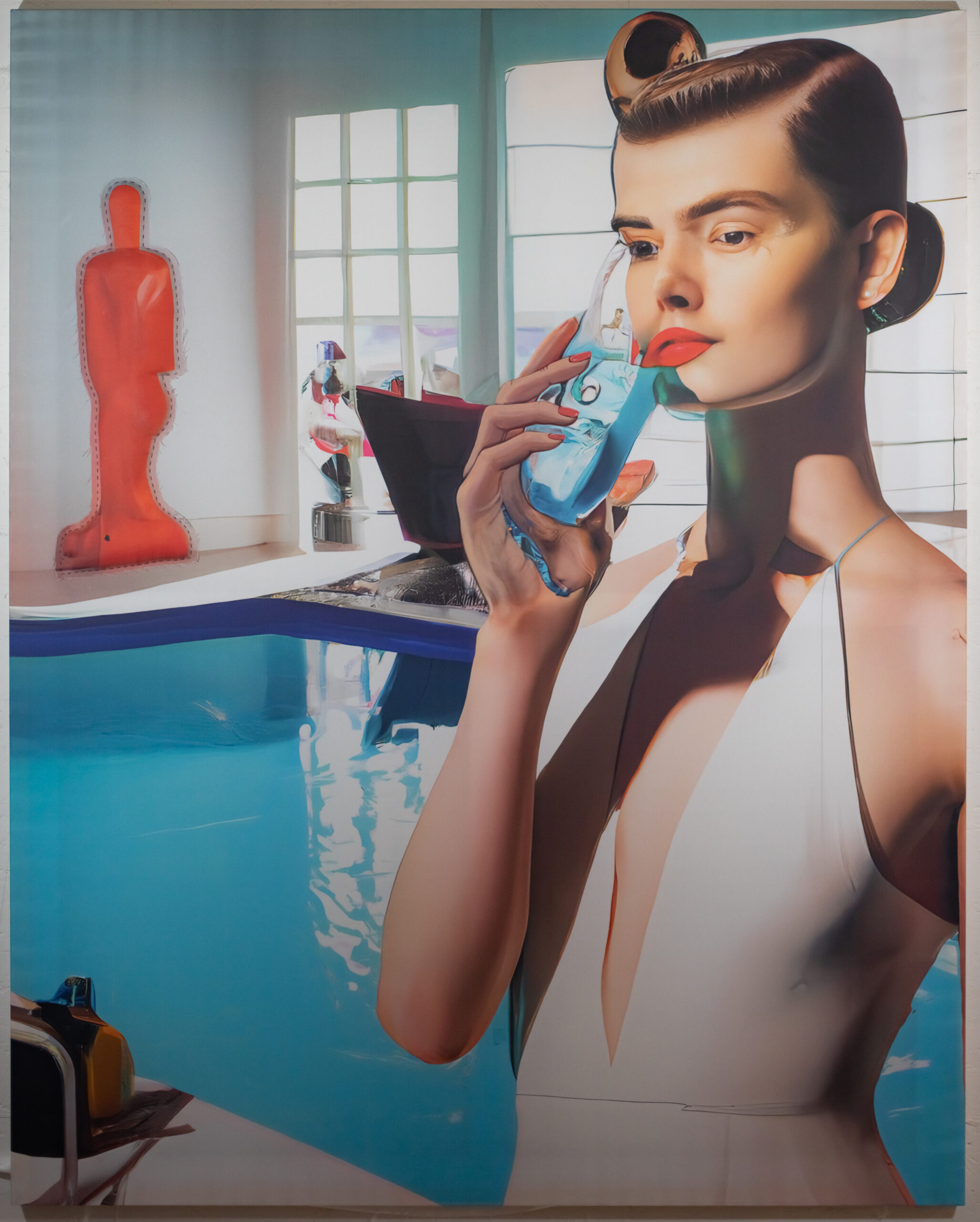

Last week, Autofiction, a new exhibition by Laurie Simmons, opened at the YoungArts Jewel Box in Miami, marking the artist and photographer’s official foray into Artificial Intelligence, which she’s leveraged to recreate scenes from her own life using platforms like DALL–E and Stable Diffusion in both this new show and In and Around The House II, her recent exhibition with the photography organization Fellowship. “We came up together as kids,” she told the artist Walter Robinson a few weeks before the opening of her now show. “And here we are, one million years later, both using this new technology that some people think is the gateway to the end of the world.” Unlike much of the art world establishment, Simmons and Robinson are feeling rather Pollyannaish about the possibilities of A.I., which Robinson relates to “that 1960s, 1970s [idea of] a language-related conceptual art”—just with bigger boobs. “Images of beautiful, busty young women,” he explains, “there has to be the largest number of that particular image in the world.” On Zoom, the two visionaries talked about polyamory, Midjourney, and the “erotic plenitude” of A.I.

———

LAURIE SIMMONS: Should I start? But I don’t see you.

WALTER ROBINSON: You don’t see me?

SIMMONS: No. This is a brand new computer I set up yesterday. Oh, now I see you.

ROBINSON: It’s nice to see you! I feel humbled. The new A.I. work is so great.

SIMMONS: Thank you.

ROBINSON: You’re preparing for a show in Florida, right? Do you want to talk about that?

SIMMONS: I do. I think this whole thing came up because Fellowship, who I’ve worked with a lot for my A.I. work, had a booth at Paris Photo. The whole idea that Paris Photo, this bastion of both traditional and contemporary photography, could have such a big focus on A.I., because obviously, there are questions about not only whether A.I. is photography, but whether it’s art at all. I also went to an opening in a small Connecticut town and saw two of your works, which were both beautiful, and one was an A.I. generated work.

ROBINSON: That’s right. Actually, the painting was a painting I made from an A.I. image. It’s a kind of photograph, in that it’s an inkjet print, but it’s on canvas and the image is generated by A.I.. I suppose your work is similar, right?

SIMMONS: Yeah. We came up together as kids. And here we are, one million years later, both using this new technology that some people think is the gateway to the end of the world.

ROBINSON: That is so true. It’s so bizarre, the resistance to it. From my point of view, they want the artist’s hand. They want that messy, muddy stuff on the end of a stick rubbed over the canvas.

SIMMONS: Who is “they”?

ROBINSON: Idle passers-by. As my old boss, Charlie Finch, used to say, “My readers never ceased to disappoint me.”

SIMMONS: To get to the essence of it, you and I, unlike some of our colleagues, are on record as being really interested in language. We both write. We both talk okay. We’re not afraid of talking about our work, or talking about anyone else’s work. For both of us, the idea of text to image was a great platform. That’s how I feel about it. I feel like, “Oh my god, I can take these sentences and twist them, and work with them, and generate these images from two parts of my brain.” I don’t know if you feel that way. I don’t want to put words in your mouth.

ROBINSON: It’s fascinating, the parallels between using an A.I. prompt. For instance, I want to prompt a picture of a couple passionately embracing. It’s very much the same as an idea an ordinary painter would get for an artwork. For me, it’s conceptual art. The same as Sol LeWitt making a rule like, all the lines drawn from one side of a canvas to another, it’s the same way the A.I. accepts a rule. In a way, it goes back to that 1960s, 1970s [idea of] a language-related conceptual art.

SIMMONS: Yeah. We both come from that deep-rooted connection to conceptual art. In my case, I’ve always invited other people in. I invited body painters in more recently, to paint children and family, to paint eyes on models. I’ve always had illustrators draw things. I was always pulling in from other image sources because I always felt so inept as an artist. I thought, “I need help here.” Everything that’s happened in technology has been such a gift for me, starting with the world wide interweb, then Photoshop, and now A.I. I couldn’t dream up how much it would benefit me and my work.

ROBINSON: Oh, you’re so right. As a tool, it makes everything so much quicker and so much easier. It’s also so much fun. I use Midjourney, too, the app on my phone. It’s possible to devise images while I’m riding on the subway. You can do the work at any time. It has parallels to that unwrapping fetish, where people do videos of themselves unwrapping stuff.

SIMMONS: It is a present!

ROBINSON: I’m sitting there, going, “Oh, that’s a good one.”

SIMMONS: I feel the same way.

ROBINSON: It reminds me of what Richard Prince used to say when he was working in the Time Life photo library and he’d see a new Marlboro cowboy and think to himself, “Oh, that’s a good one.” I do see that post-modernist circulation of signs at work. I’m tapping into the vast inventory of images that society generates.

SIMMONS: Exactly.

ROBINSON: Unlike you, I’m timid in my studio. I don’t collaborate with people very often. I let the A.I. be my collaborator, like you said.

SIMMONS: The thing that we have to acknowledge about A.I. is that we’ve never had a tool that was developing faster than we are developing. It is working overtime while we’re sleeping. The things that I started to do when I first started working in August 2022 are so rough and cartoonish, in a way that I really love. The programs can’t even generate images that are primitive anymore because they’ve gotten so good. We will have to discuss the end of the world, and these things becoming sentient, because we have to be responsible. But we can do that at the end of our conversation. [But] when I generate images, it looks like a picture I would’ve made. I feel like it’s just dipping into my subconscious and pulling out exactly the right stuff.

ROBINSON: Absolutely. That’s what makes us, as artists, somewhat separate from the public discussion about A.I. Because we’re imposing our own authorship on the imagery. I noticed that, with your works, they look very much like Laurie Simmons works. And with my paintings, people ask, “How did you get it to look like the kind of imagery you work with?” Of course, all that’s done in the prompts, but as artists, we still retain our individuality and our unique subjectivity, even working with the A.I. It’s so interesting, the contrast between finding pictures out there in the public versus generating your own versions of the pictures. For instance, one of the things I like to paint are piles of cash. I can find photographs of piles of cash that suit me much more than the piles of cash that Midjourney will generate. You can find lots of photographs of cash on thug websites, because the drug dealers love to boast about their huge piles of cash. I love that kind of imagery.

SIMMONS: I love this. This is so obscure. Keep going.

ROBINSON: My joke is that Warhol did $1 bills. I do hundreds, because we have inflation. Aesthetic inflation.

SIMMONS: Right. The backgrounds of many of the things that I’m generating look exactly like the backgrounds I used to borrow and plagiarize from the picture library. I would look for red rooms and there would be these really dirty manila envelopes full of lots of pictures, on cardboard, of red rooms. Then, you check them out, and take them home. They’re disgusting, actually.

ROBINSON: Yeah. The digital revolution has certainly made my job as a writer easier. I have a similar group of files, but they’re all on my laptop.

SIMMONS: That’s where they’re really great. Parenthetically, I wrote my first Artforum article in 2000. I wrote a very long article about Jarvis Rockwell, Norman Rockwell’s sad younger brother, and it was only because I could write on my computer, paste and cut. The computer, with my ADD mind, allowed me to begin writing. I credit the computer for even letting me into the writing world.

ROBINSON: Did you see the cartoon on the cover of this week’s New Yorker? It’s an artist with a stack of paper he’s crumpling and the A.I. robot comes and ends up taking the paper and crumples it up into a huge pile of crumpled up paper.

SIMMONS: I like that joke. I have a question for you. While I am making all this new work and being really excited about it, it’s impossible to keep up with the A.I. conversation, both negative and positive. On any given day, you can read one article in one major newspaper about how A.I, will eventually be curing cancer or how A.I, will mark the end of the world. And of course, all of the programs are sexist and racist and there are a number of artists who are making that aspect of A.I. their area of inquiry, and I really respect that. I listened to a podcast by a guy called Lex Fridman and various other people who really know about the future of A.I. Opinions about it are across the board. When I picked up a camera in the mid-seventies, the history of photography was about 135 years old, so it was easy for me to learn the history at the same time that I was learning to use a camera. I feel a responsibility to understand the information around A.I,, but that information is coming at us so fast and so furiously.

ROBINSON: So much of that is over my head, which is a nice way of saying, “I’m not that interested in it.” I can tell you I did notice, almost immediately, that images of beautiful, busty young women, there has to be the largest number of that particular image in the world. There are more pictures of pretty girls than anything else. I have to adjust my prompts to Midjourney to avoid having them all have giant boobs. That’s my index to the sexism of it. But at the same time, to quote Svetlana Alpers, “It’s an erotic plenitude out there.” Strangely, it’s more difficult to find images of men that I like, as opposed to images of women. Of course, I’m more interested in images of women. How do you choose your subjects?

SIMMONS: Maybe you haven’t been paying attention, but I only had one subject for 40 years. It’s a woman in an interior space, whether we’re talking psychologically and philosophically, or a woman in a room sitting on a couch. It’s always one to three women. The series that I’ll be showing at Young Arts in Miami is called Autofiction. In a sense, I’m comfortable knowing that every single image that I’ve made is a version of me. It’s really autobiographical. I’m really terrified, if it is not about me, to see what A,I. will serve up. I’ve tried to get crowds that are more racially diverse. I’ve tried to do images of men. The only thing that I can be comfortable with is some version of myself. If it resonates with me in some way as a self-portrait, then it’s in. I made these very limited parameters. It sounds like you’ve kind of limited your parameters, too. It’s interesting that we would both limit our parameters in a space where we can do anything. All these assholes working with A.I. are like, “Make the moon a watermelon and the sun an orange and the sky is green instead of blue.” I’m like, “Are you kidding me?” You can do anything, but I think having the possibility to do anything just makes me close down.

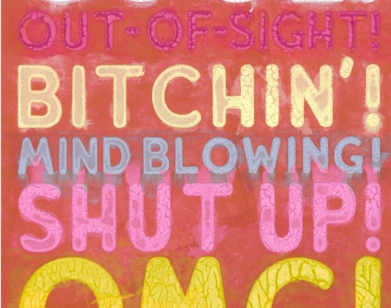

ROBINSON: It comes down to a question of individual sensibility. Just because an artist has access to A.I. doesn’t mean that the art they make with it is going to be any good. Or, should I say, is going to suit us. Another thing that bugs me is the aesthetic impulse to make something that looks cool. When it comes to the visual appearance of my work, I’m just trying to make it look good. But somehow, as an aesthetic bottom line, I don’t like that. I want it to have some other kind of meaning, as well as looking cool.

SIMMONS: Do you think that 40 years of having our own imagery, vernacular, and sensibility makes it easier for us to work in the arena of A.I.? We know what we’re looking for, whereas a young artist is just approaching the blank canvas of A.I., having to find a style there.

ROBINSON: You see a lot of young artists who are making figurative paintings and their styles are all very individual. I wonder how you could use A.I. to get that same kind of peculiarity. I know, in my case, I’m working with templates. I’m looking for a certain kind of image that has this resonance to fifties and sixties pop. I started out thinking that it was really plain, that I wasn’t making a big deal out of the technique. I may have been mistaken. But I don’t know if you could go into A.I. and develop your own subjective, individual imagery the way so many of these painters do.

SIMMONS: Since my first photographs, I’ve been interested in interstitial spaces between reality and fantasy, or humans and surrogates. It’s always the in-between spots. That’s another reason that A.I. appeals to me. I was also thinking about how much you’re a grandfather—or, if you want to be the father, I’ll give you that—to so many of these young artists. In so much of the work, I can see your fingerprints.

ROBINSON: Thank you very much. For me, paint is always the final alibi. Besides anything else, I am making paintings, and I want it to look like it’s made with paint. That’s the last excuse, the idea that painting itself offers some kind of special relationship to the self, the body, and the material world. Painters can be annoying when they claim that kind of special quality to painting itself.

SIMMONS: But it’s amazing that painting is still viable, appreciated, and literally exists in the world that we’re in. My appreciation for painting has only grown. I remember in the late eighties being so angry at Jimmy DeSana for printing a photo on some canvas, because I thought that he was betraying the photographers and trying to make a painting, thus trying to make more money. I was very angry at my best friend for doing that. Here I am, all these years later, finally finding a way to make my own painting and put my own marks on it. The fact that this technology seems to have allowed me to pick up a paintbrush and paint seems really ironic, but it’s true.

ROBINSON: I guess we were all pretty doctrinaire back there in the eighties, huh?

SIMMONS: This is why I love my kids and young people so much, because once you declared your lane you did not swim outside your lane. You were a painter. And back then, of course, you were gay or you were straight. Things were so absolute. Now, everything can swim together and I really appreciate that.

ROBINSON: We’re also polymorphous, polyamorous.

SIMMONS: I’m not polyamorous, but maybe I’m polymorphous. What’s the word I’m looking for?

ROBINSON: Interdisciplinary?

SIMMONS: Yeah, I’m interdisciplinary. That’s such a good word.

ROBINSON: I have an interesting story. With Midjourney, I was trying to do Adam and Eve, and the program was doing very well. It was giving me a couple surrounded by leaves and fruit. And all of a sudden, due to some kind of unknowable glitch in the program, it started giving me trios of people. It’d be two guys, two Adams and an Eve, or two Eves and an Adam, and everybody looked totally happy. So I can blame this notion of a polyamorous Eden on Midjourney.

SIMMONS: [Laughs] The ascension to A.I. brain that you encountered that day definitely was polyamorous.

ROBINSON: As magical as A.I. is, it does have its limitations. It seems very bad at following instructions. But you probably know that Midjourney is so G-rated. They ban any prompts using “nudity,” “naked.” They ban “sultry” as a word. They ban “tied up” as in, “she has her hair tied up in a bun.” They ban so many words that I console my illustrator friends by saying, “All of human sexuality, that’s still your stuff.”

SIMMONS: And yet, as you say, sometimes we’ll give a prompt and get a woman in a low-cut dress with breasts and cleavage so huge that it’s like, “Are you training this program with Playboy Magazine?” Anyway, I really wanted to go negative on the future of A.I. and all the terrible things, but you’re such a positive guy, Walter.

ROBINSON: I’m a Pollyanna.

SIMMONS: A polyamorous, Pollyanna, polymorph.