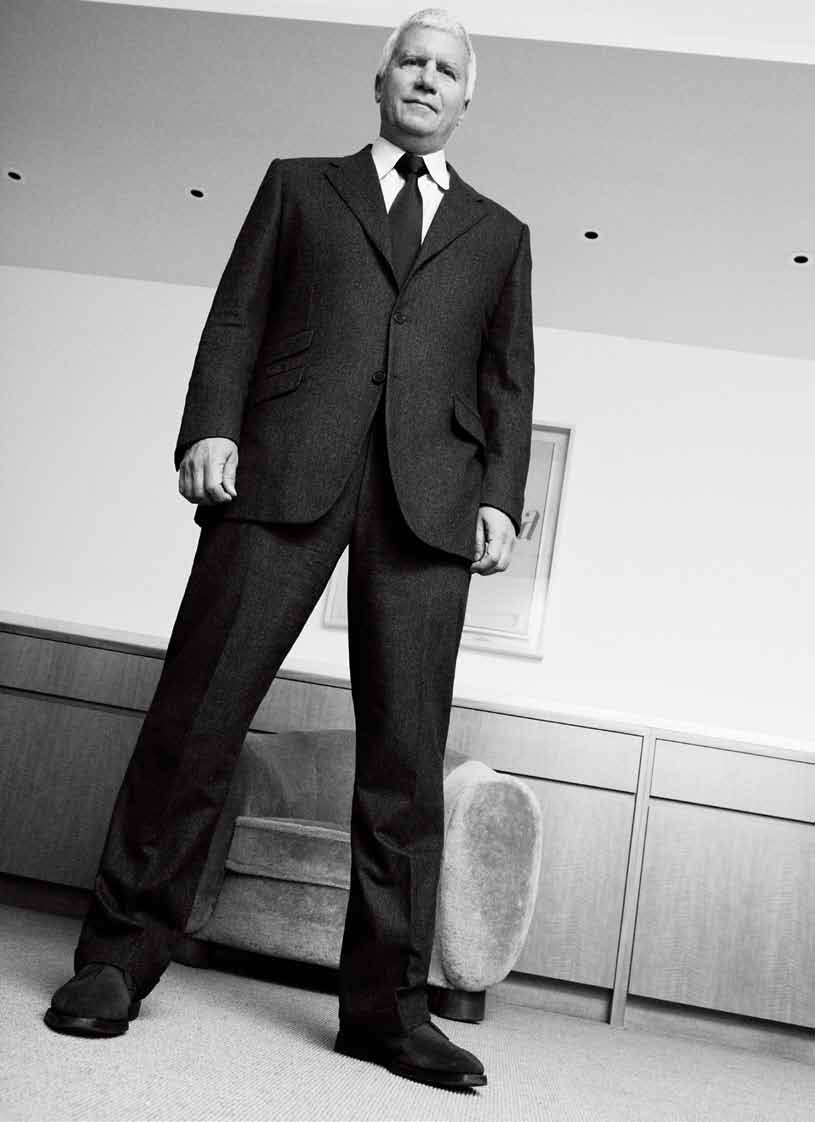

Larry Gagosian

I didn’t get into selling posters because I thought that it would be a path to becoming an art dealer. I didn’t really conceptualize at that point that being an art dealer was a profession.Larry Gagosian

If there is an art to dealing in art—and any experienced gallerist, collector, or museum director will tell you that there most certainly is—then one of its greatest practitioners is Larry Gagosian. Over the last three decades, Gagosian has built one of the art world’s most expansive (and frequently emulated) global enterprises.

Gagosian Gallery in New York, which Gagosian first opened in 1985 in the then-art-barren neighborhood of Chelsea, now boasts 12 outposts worldwide (three in New York, two each in London and Paris, and one apiece in Beverly Hills, Rome, Athens, Geneva, and Hong Kong)—the newest, a cavernous space near Le Bourget airport just north of Paris, which opened in October with an exhibition of Anselm Kiefer paintings and sculptures. The roster of talent that Gagosian has exhibited reads like a who’s who of modern and contemporary art, including the likes of Jeff Koons, Richard Prince, Ed Ruscha, Richard Serra, and Cy Twombly, younger artists such as Taryn Simon and Urs Fischer, and iconic masters such as Francis Bacon, Constantin Brancusi, Roy Lichtenstein, Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol, among others. Museum-quality historical shows have also always played a major role in the gallery, with rigorously curated exhibitions focusing on specific moments in art or thematically arranged groups of work, and featuring pieces on loan from a variety of institutions and private collections (which are very often not for sale). But while representing artists and the estates of artists remains the gallery’s primary function, Gagosian has also been heavily involved in art’s so-called “secondary” market: facilitating the private resale of works between collectors and institutions. It’s a part of the art business that remains a point of near-constant speculation, if only because it occurs largely behind the scenes and thus encourages debate as to who is selling what and why. But it’s an area in which Gagosian—with his extensive network of contacts, deep well of resources, and uncanny ability to source and deliver hard-to-get pieces—has long been a dominant player, brokering deals that have been reported to reach nine figures for a single work. In addition, Gagosian is himself a collector, and has invested in several other art-related projects, including Art.sy, a recently launched website dedicated to selling art online.

The interconnected nature of all of Gagosian’s various art-related activities has helped fuel the gallery’s growth, which has very neatly occurred in tandem with the globalization of the art market, as attendance at international art fairs booms and new segments of collectors continue to emerge from places like Asia and Latin America. But more than sheer size or clout, it’s the model around which Gagosian and his gallery operate that has permanently altered the landscape of the art-dealing business.

Gagosian, 67, very rarely gives interviews. Nevertheless, he agreed to sit down recently at his office at 980 Madison Avenue with Interview‘s chairman, Peter M. Brant, a longtime friend, for a wide-ranging conversation about, among other topics, his entrée into the art world, the evolution of the art business, his plans for the future, and, perhaps most importantly, the work at the center of it all.

PETER M. BRANT: We’ve known each other and done business together for more than 30 years, but I wanted to start at the very beginning. What was it like for you growing up in L.A.? Was there ever any sign that you would wind up choosing this life?

LARRY GAGOSIAN: Honestly, I grew up in pretty modest circumstances. We were a middle-class family. I think at one point my mother might have been lent a couple of little seascapes by a friend, but we didn’t really have any art at home. I don’t even remember if I went to a museum before I graduated from college. I may have gone to the L.A. County Museum of Art once or twice, but that would’ve been it.

BRANT: Your mom was an actress, wasn’t she?

GAGOSIAN: My mom was an actress. She wasn’t a big actress, but she made a handful of movies. She was in one called Journey Into Fear [1943], which starred Joseph Cotten. She played a nightclub singer. The film was produced by Mercury Productions, which was Orson Welles’s company. Orson Welles didn’t direct it, but he was in it and involved in it, and Joseph Cotten wrote it. He worked very closely with Welles.

BRANT: And your dad was an accountant, right?

GAGOSIAN: My dad was an accountant for the city of Los Angeles. He was a civil servant.

BRANT: So when did you first start thinking about art? What were the first things that got your attention?

GAGOSIAN: Clothes. I was always very focused on how people dressed. Appearances. But as far as getting into fine art, I’ll tell you a funny story: I was an English literature major at UCLA, and I had a class with a professor who, for some reason, was sort of anti-avant-garde art. When I look back on it now, I realize he probably just didn’t like abstract art. But I didn’t even know what abstract art was at the time. So one day in class we were having a conversation that went from talking about literature to talking about aesthetics, and he was basically saying, in so many words, that contemporary art and abstract art were not worthy of serious consideration—that they were superficial and overrated, which was a funny comment to hear in an English class at UCLA. To illustrate the point, he said, “If you look at this da Vinci or this Raphael, you can go from the eyes to the woman’s navel and there is a perfect triangle. But now we have artists who paint a triangle and they call that art.” For some reason it just bugged me, that comment. So I stuck my hand up, which I didn’t do very often, and said, “Maybe sometimes you just want to look at a triangle.” But that sticks out in my memory as something that got me thinking about aesthetics.

BRANT: How old were you then?

Andy [Warhol] and Cy [Twombly] were very instinctive and made their own decisions. They were part of an art world that doesn’t really exist in the same way anymore. I miss those kinds of artists”-Larry Gagosian

GAGOSIAN: I was probably 18.

BRANT: You swam at UCLA, didn’t you?

GAGOSIAN: Yeah. I swam and played water polo. I swam in high school and for my first two years at UCLA, but I was just outgunned. I was a good high-school swimmer, but UCLA had a national-caliber team, so after two years I quit.

BRANT: You finished college in ’67 or ’68?

GAGOSIAN: Actually, in ’69, because I dropped out a couple of times. Took me six years to graduate, then I had a series of what you might call odd jobs. I worked at a free-press bookstore. I worked at a record store.

BRANT: You worked at William Morris Agency.

GAGOSIAN: William Morris was my only real job. That lasted a little over a year. I just wasn’t cut out to be a theatrical agent, but I worked briefly for Mike Ovitz—I was his secretary. I also worked for a terrific agent named Stan Kamen. That was really the highlight of my career there because Stan represented Warren Beatty and Steve McQueen. Stan had everybody. So that was a very dynamic place to work, but I just didn’t have my heart in it. I didn’t really thrive in that kind of competitive office atmosphere. I just wasn’t wired that way.

BRANT: How did you get into selling posters?

GAGOSIAN: Well, that was kind of a fluke. I’d been fired from the William Morris Agency, so I was parking cars—that was my job—but I didn’t really have any particular ambitions or financial aspirations. I think at that point I was living in a walk-in closet in somebody’s house in Venice Beach, and I was just happy to have some good friends. But I had no money, so I got into selling posters after seeing somebody selling posters on the sidewalk. I just basically copied this guy’s business. I even went to the same place he went to buy his posters, Ira Roberts of Beverly Hills, which was a company owned by the father of Michael Kohn, who has a gallery in Los Angeles. They were publishers of these low-end posters that you could buy for about a dollar, put a frame on, and try to sell for $15. But I didn’t get into selling posters because I thought it would be a path to becoming an art dealer. I didn’t really conceptualize at that point that being an art dealer was a profession. But then I started selling some more expensive posters.

BRANT: And your business started to evolve . . .

GAGOSIAN: If you want to call it evolving. I just sort of worked it up. I remember that Ira Roberts would print these little pamphlets to advertise the schlock posters they were selling, but on the last page they’d have posters that were more expensive, so I started trying to see if I could put a frame on one of those and maybe get $200 or $250. But that’s what really got me excited about art. It was really kind of a street business for me. Then I got my own frame shop. Kim Gordon from Sonic Youth was my framer. In fact, she came to New York around the same time I did, and that’s when she started her band.

BRANT: But as far as learning about art, from that point on, you were really just self-taught.

GAGOSIAN: Exactly. I never really took a proper art class in college. I just started reading art magazines and going to galleries. I was really drawn to it.

BRANT: When did you start the Broxton Gallery?

GAGOSIAN: I started that in ’76, I believe. My first show at the Broxton Gallery was Ralph Gibson. The reason I got that show was I’d seen a reproduction of one of Ralph’s photographs in an art magazine, so I tracked Ralph down by calling information in New York.

BRANT: I’ve always read about this show you had at Broxton in the mid-’70s called “Broxton Sequences: Sequential Imagery in Photography,” which included work by people like John Baldessari and Bruce Nauman. You showed a lot of photography early on at Broxton.

GAGOSIAN: Whether it was a William Wegman or Chuck Close or Jan Dibbets, I just liked the way the format of photography looked-the structure and purity and coolness of it. At that point, it was just something that caught my eye. But my first show that wasn’t photographic was Vija Celmins. I really loved Vija Celmins’s work, and I was able to assemble her entire oeuvre of graphic work. Then I started buying Ed Ruscha’s books. I got Alexis Smith. Chris Burden was an early show. I just went into the L.A. art scene at the time, and, luckily, it was a city where there were a lot of great artists.

BRANT: How did you end up coming to New York?

GAGOSIAN: That actually goes back to Ralph Gibson. I initially thought that Ralph lived in L.A., but I eventually got him on the phone and said, “I’ve got this poster gallery in Westwood. Would you consider giving me a show?” Of course, he’d never heard of me, but he was a nice guy, so he said, “Well, you have to come to my studio.” I’d only been to New York once before to visit my aunt and uncle for three days. But I went and visited Ralph’s studio on West Broadway, and he was very open to me. Turned out Ralph was represented by Leo Castelli, so I met Leo through Ralph, which was also very fortunate.

BRANT: How did you meet [art dealer and gallerist] Annina Nosei?

GAGOSIAN: I’d started buying some small works and drawings. I’d bought a Brice Marden piece. I’d bought a Sol LeWitt drawing. I was still kind of drawn to minimal art. It was more accessible at the time—by which I mean, less expensive. So at that point I was scraping around trying to do some art deals, and Annina called me up one day and said, “You’ve been buying work from people that I represent. We should meet.”

BRANT: She was married to John Weber at the time?

GAGOSIAN: I think they might have been separated or divorced at the time; I don’t recall. In any case, Annina and I hit it off. I didn’t know who she was, but she was a very warm, intelligent woman. I’d just gotten this loft on West Broadway, which Peter Marino designed for me . . . Well, to say that Peter Marino designed it is misleading because it involved, like, a can of paint. But Peter and I are still friends, so it was a nice start for that friendship as well. He was just starting to do his own thing back then. He looked very Ivy League.

BRANT: Who would you say was your first big client?

GAGOSIAN: There were a couple of people. Eli Broad was probably my first client in California. We’re still good friends, and he’s been a great support for my gallery. In New York, I’d say that Si Newhouse was probably my first big client. I bumped into him on the street with Leo Castelli. Some other art dealer might have hustled me across the street, but Leo made a very nice introduction—that’s just the way Leo was. I think I called up Newhouse the next day.

BRANT: Wasn’t [ad exec and television producer] Doug Cramer an early client?

GAGOSIAN: Doug Cramer was a client very early on—maybe even before Eli, now that I think about it. [TV executive] Barry Lowen was also a great client—in fact, he and Doug were always in competition. Unfortunately, Lowen died many years ago. But that taught me a little bit about the art business, about how collectors are competitive, and how, as a dealer, you could sometimes use that to your advantage.

BRANT: One of the first shows you did in New York was the David Salle show in your loft that you did with Annina. How did that happen?

GAGOSIAN: That was in 1979. I’d just gotten the loft, which I’d fixed up pretty much on the cheap, and I’d seen a photograph of a David Salle painting in a magazine. It was a 1978 painting from when he was just starting, where he’d overlay images. I thought it was really beautiful, so I called Annina and she said, “Oh, I know David Salle. We could go to his studio.” Salle was living in Brooklyn at the time, so we went to his studio, and he had seven or eight of these paintings from the same series. On the spot, I said to Annina, “Let’s do a show in the loft,” and that was the first show I did in New York. It got reviewed in Art in America. Bruno Bischofberger bought a painting. Charles Saatchi bought one. The de Menil family bought one. A lot of people came to see the show, so it was a nice way to get a little traction in the art world in New York. I think the paintings were about $2,000 each. I kept one. I still have it.

BRANT: You were one of the first people to really recognize Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work. How did you meet Jean-Michel?

GAGOSIAN: I was in my loft, and I got a phone call one afternoon from Barbara Kruger, who I’d gotten to know, and she said, “Larry, I’m in a group show at Annina Nosei’s. The opening is this afternoon. I’d love to have you come over and see it.” So I walked over to Annina’s gallery on Prince Street. As I recall, the way Annina’s gallery was set up was that there were two rooms, one larger and one smaller, that led to her office in the back. In the room that was closest to Annina’s office, there were these paintings that just electrified me. I’d never heard the name Jean-Michel Basquiat before. I didn’t know if it was a man or a woman, to be honest with you. But I met Jean-Michel that night because he was in Annina’s office. I was startled when I saw him because he wasn’t what I was expecting to see. He was this great-looking young black guy with hair that stood straight up. I think he was wearing white painter’s pants that were splattered. But I liked him immediately and we became friends, so I went on to show his work in Los Angeles.

BRANT: How long after you met him did you first show his work?

GAGOSIAN: It was less than a year. He was painting in Annina’s basement at that time. It was just wild to go down there and see what he was working on.

BRANT: Jean-Michel came out to live with you in L.A. for a while, didn’t he?

GAGOSIAN: Yeah. We came out to L.A. when we did that first show, and I think he liked it there. He’d never been to L.A. before, and it was a change of scene, different people. So he came out and moved into my house for about a year.

BRANT: Tell me about the flight you took with Jean-Michel back to California.

GAGOSIAN: Oh, jeez. Can I tell you that? [laughs]

BRANT: Didn’t he and some friends light up a spliff in first class?

GAGOSIAN: Jean-Michel was smoking a little bit of everything at that point, and he lit up a joint in the first-class lounge. I remember the stewardess didn’t really know what to do with these guys—I mean, these were serious, urban-looking guys. One of them was Rammellzee, who had on a white leather trench coat and ski goggles. So we were having a good time, and the stewardess came up and said, “You can’t do what you guys are doing in here.” So Jean-Michel goes, “I’m sorry. I thought this was first class?” [both laugh]

BRANT: Jean-Michel was hanging out with Madonna at that point, right?

GAGOSIAN: Well, that’s interesting because everything was going along fine—Jean-Michel was making paintings, I was selling them, and we were having a lot of fun. But then one day Jean-Michel said, “My girlfriend is coming to stay with me.” I was a little concerned-one too many eggs can spoil an omelet, you know? So I said, “Well, what’s she like?” And he said, “Her name is Madonna and she’s going to be huge.” I’ll never forget that he said that. So Madonna came out and stayed for a few months, and we all got along like one big, happy family. There was a guy named John Seed, who was Jean’s assistant, and he was, like, our cook. He was a great cook.

BRANT: You used to drive Jean-Michel around, right?

GAGOSIAN: Used to drive him around . . . But I lost my license or something at one point, and Madonna actually became our driver for a while. Madonna drove us around. [both laugh] But she was no joke. Even then you could see the discipline and focus and ambition. She’d go running every morning. She’d do yoga. She’d be on the phone with her people. You got the sense she was serious. I wouldn’t say that we’re really friends anymore, but whenever I see her, we have this nice history.

I’ve probably rubbed some people the wrong way. I was very aggressive and tried to be correct but, you know, I play hard. So the critical stuff doesn’t surprise me or bother me.”-Larry Gagosian

BRANT: The show you did with Jean-Michel was very well-received in L.A.

GAGOSIAN: Very well-received. Shows you how talented he was. It’s one thing to have a successful show in New York with the local people, but then to move that type of work to Los Angeles and have it resonate—I mean, this was emphatically New York, urban work. Gives you a real sense of the power of the art that he was making.

BRANT: You were doing pretty well in L.A. What got you thinking more and more about New York?

GAGOSIAN: I was doing well in L.A. I had a house there—it was a really cool, modern house that actually won some architecture award. I was living right by the beach. I had a great life. But you really can’t work that hard in L.A.-at least in the art business—so I’d started to spend more time in New York. I had the loft. I was meeting artists. I was meeting all kinds of people. So gradually, my focus started to shift.

BRANT: That’s around the time when I first met you. One day, you called me up out of the clear blue. I didn’t know you and you didn’t know me. But I’ll always remember our conversation. When I first became interested in art, I liked to look at art books and see where the paintings were, and my introduction to you was that you’d seen my name in a book with some Andy Warhol paintings, so you called me and we just started to talk.

GAGOSIAN: I’d also seen you at the Castelli Gallery. We didn’t meet, but you looked like you were important, so I asked Leo afterwards, “Who was that?” That’s how I think your name got filed away.

BRANT: One of the things we have in common is that we both spent a lot of time with Leo. He certainly had a tremendous influence on my life. I know that Leo taught you a number of things, but is there one thing in particular you feel like you learned from him?

GAGOSIAN: That’s a very good question. I can’t answer it simply, but he showed me how a gallery could really make the art feel important. Of course, it helps to have work by artists like Roy Lichtenstein, Ed Ruscha, and Jasper Johns. But the way you present the work has a lot to do with how people receive and regard it. Leo always had great style in the way he presented the work—and without making it too fussy. Leo also showed me that you could have a lot of fun being a dealer. He liked to have a good time.

BRANT: Yes, he did.

GAGOSIAN: But the fact that you could have a business as serious as Leo Castelli’s and still have a wonderful life—that was a life lesson as well as a business lesson. The other thing he taught me was not to give too many interviews. In the later years of Leo’s life, we were partners. We had a gallery together, we shared artists, and we had a fairly formalized business relationship. But I’d call him up because I wanted to talk about a painting or a show or a deal, and I’d be told, “Mr. Castelli is being interviewed.” [both laugh]

BRANT: Leo always had a lot of confidence in you.

GAGOSIAN: The way Leo worked, he relied a lot on a small group of dealers who he trusted to do most of the selling. He was very open and collegial, but it also served his M.O. because he didn’t want to stand in a gallery selling paintings all day. So I was lucky enough to be one of those dealers. Some dealers tried to kind of muscle him out because they figured, “Oh, Leo is getting old. Maybe we can . . .” But I never did that. I think he respected the fact that I was aggressive, but never at the expense of our relationship.

BRANT: So what led you to open the gallery in Chelsea?

GAGOSIAN: The loft gallery on West Broadway only lasted about six months—everybody in the building was furious because there was so much traffic and we were having these big parties with music. So I had to shut that down after three or four shows. Then for the five years between 1980 and 1985, I didn’t have a gallery in New York. I wasn’t even looking for a space. But I was standing on the street on West Broadway one day with my friend Peter Bonner, who said, “I want you to see a space that I’m thinking of renting in Chelsea.” I got in his car and we drove over to West 23rd Street. It was in a building that was owned by the artist Sandro Chia. We went up to Chia’s loft and sat down and had a bottle of wine. I’d never met Chia before, but I said to him, “When I came into the building, there was a truck parked at a dock on the ground floor. What are you going to do with that space?” He said, “I don’t know. I’d like to rent it, but I don’t want a restaurant. Restaurants call me up all the time, but I don’t want to have food in the building.” So I said, “I’ll take it.” And that was it.

BRANT: At that time, there weren’t really any galleries in Chelsea.

GAGOSIAN: None. There were junkies. There were prostitutes. It’s hard to imagine how much that neighborhood has changed. But up to that point, I didn’t really have an idea to have a gallery in New York. I wasn’t thinking about it. I’d looked at no other spaces. You’re the one who tipped me off about 980 Madison.

BRANT: The magazines had their offices here.

GAGOSIAN: Art in America had their offices, right?

BRANT: Right.

GAGOSIAN: So I opened this space in 1989.

BRANT: I was very impressed by the early shows at the 23rd Street gallery—some of which, I think, rank among the greatest shows I’ve ever seen at a small gallery. There was the Lichtenstein-Picasso show, the show of the De Kooning abstract paintings from the mid-’50s [“Willem de Kooning: Abstract Landscapes 1955-63,” 1987], the Warhol “Most Wanted Men” show [1988], the big Twombly works-on-paper show [1986] . . .

GAGOSIAN: We opened with the Tremaine Collection [“Pop Art From the Tremaine Collection,” 1985]. That was the first show.

BRANT: Those early shows were very well-curated—and forerunners to the big blockbuster Chelsea shows you have now. How did you go about putting together shows of that stature early on?

GAGOSIAN: Well, when I was in L.A., I was able to show a lot of Leo’s artists and work with other dealers and be kind of like a satellite. But when I came to New York, I didn’t have any so-called “primary” relationships with artists, because they all had relationships with other dealers, so the only way I could get access to great artists was really by doing these historical shows. I didn’t have the means to do even a small retrospective, so I seized on the concept of doing small, focused shows, which were just a way of having something great in the gallery without having access to an artist. I didn’t represent any artists at that time. You also had to get people to Chelsea. There was no Dia [Art Foundation]. There was nothing there. We did the “Most Wanted Men” show after Andy died. But we actually did a show with Andy on 23rd Street while he was still alive, which was one of his last shows of paintings.

BRANT: The show of the oxidation paintings. Most of those early shows were really put together based on connoisseurship, though. They were not really about selling the works, because a lot of collectors already owned them.

GAGOSIAN: Right.

BRANT: At that point, you must have seen that those kinds of shows were going to be an important part of your future.

GAGOSIAN: Well, it’s a formula—if you want to call it that-that I still use. I think it creates a nice rhythm in the schedule of the gallery to go from showing new work by a living artist to doing a historical show. They’re still an important part of the gallery.

BRANT: What shows stand out to you the most? Which of the shows do you feel really mattered?

GAGOSIAN: I like different ones for different reasons. One that stands out is the Brancusi show we did at 980 Madison in the early ’90s. It took a lot of work to get Romania, which had just become a democracy, to send the Brancusis to my gallery from the national collection and museums in Craiova. It was also very controversial. There were incredible stories about the show in the Romanian press—that it was some kind of a scam, that we were going to sell the Brancusis. Of course, we had no intention of selling them, but what made that show memorable was just all the logistics involved. A lot of times it’s not the show so much as the effort it took to pull it off. For example, getting Frank Sinatra to sell an Edward Hopper painting. I had to call so many people and friends of his and his son-in-law and his wife, Barbara . . . I worked on that for so long. I really wanted that painting.

BRANT: How did Sinatra get the Hopper? Was he just interested in art?

GAGOSIAN: Frank liked art. He had a collection. There are great photos that just came out in this book of Frank with Picasso in the South of France. I think the Picasso-Lichtenstein show was another great show. The shows we’ve done with [Picasso biographer] John Richardson have been incredible. I was very proud of our Monet show and of the de Kooning show. But it’s usually where there’s the greatest struggle to get the pieces that you appreciate things the most.

BRANT: I know that one of the artists you worked with who you were very close with was Cy Twombly, who passed away last year. How do you think about the times you spent with him and his work?

GAGOSIAN: I think about Cy a lot. I really miss him as a friend, and I certainly miss going to his studio and seeing new work. It was always a treat. I spent a lot of time with him. We vacationed together. We talked a lot. I don’t know what pure means, but if it means anything, it certainly would apply to Twombly. He was unlike any artist I ever met. He never drove a car, never owned a television. He didn’t really care about money-he was no fool, but he certainly wasn’t driven by money. He just lived his own life and was totally an artist-all in, all the time. And then leaving New York and moving to Italy and totally going against the tide . . .

BRANT: Of all the artists I’ve met over the years, Cy was, for me, one of the most interesting. There was something charming about him. He was a gentleman. I visited him once in Rome in 1973. We had a film in the Rome Film Festival that I produced with Andy called L’Amour [1973], and Cy invited us up to his apartment.

GAGOSIAN: His palazzo.

BRANT: Yeah, his palazzo. It was so impressive. I remember he had this bed with these white linen sheets, and behind the bed, he had Andy Warhol’s The Kiss (Bela Lugosi) [1963].

GAGOSIAN: Then he worked in Lexington, Virginia, which is where he was born. It was there that he painted Lepanto, which is an amazing cycle of paintings. He did those paintings in a studio that was like a shoebox. It was about 15-by-25 with 8-foot ceilings. The canvases were too big for the space so they would extend out on the floor. He painted incredible work in that studio.

BRANT: He never had too many people to the spaces where he was working.

GAGOSIAN: No, he never was a guy who did studio tours. But he was so much a part of the art world. He removed himself physically in many ways by living in Rome, but he was still more connected than a lot of artists who live and work in New York.

BRANT: And then, in his later years, he also did the Bacchus series of paintings, which were such a home run.

GAGOSIAN: So powerful and vigorous. I mean, talk about late work. How many artists go out like that? In his eighties, Cy was painting these huge, muscular paintings.

BRANT: You consider him one of the great painters of the postwar period.

GAGOSIAN: One of the great painters, period. That’s why they’ve done all these shows. They’ve put him with Poussin. They’ve put him with Monet. I don’t think those are silly connections. I think they’re pretentious connections, but how many artists could hang in that kind of company? Think of Matisse, think of Picasso, think of very few artists at the ends of their careers. Most artists kind of shrivel up. They get tighter. They sometimes lose their physical strength. But Cy was just exceptional.

BRANT: What about Andy? You showed his work after he passed and were very instrumental in helping to establish how great some of his later work was. How did you meet Andy?

GAGOSIAN: I probably met Andy in 1980. I didn’t really have a relationship with him, but I’d see him at the Castelli Gallery or on the street. But then I got to know Fred Hughes, and Fred was the guy who made a proper introduction and invited me to the Factory.

BRANT: Fred was really the one who made most of the show connections for Andy. He was a very dear friend of mine-and a very talented guy, too. How did the show of Andy’s oxidation paintings happen?

GAGOSIAN: I was having lunch in the studio with Andy and Fred, and as we were sitting down to eat, I saw these rolled-up canvases on the floor that were kind of metallic-looking. So I said, “What are those?” And then Andy said something to the effect of, “Oh, those are these oxidation paintings.” He probably called them “piss paintings”—Andy wouldn’t use a fancy word like oxidation. In any case, Andy said that nobody liked them, but I said, “Well, let’s take a look.” So me and Fred and Andy literally unrolled two or three of these 20- or 25-foot paintings on the studio floor, and I said, “I think they’re pretty cool.” I didn’t know the history of them at that point-that they’d been done a few years earlier.

BRANT: In the late ’70s . . .

GAGOSIAN: Yeah, and this was, like, ’85 or ’86. So, I can’t remember if it was Fred or Andy who said it, but one of them said, “Well, do you think you could sell them?” [laughs] So we did the show on 23rd Street. At that point, Andy was a little bit like Cy, in the sense that they were both represented by Leo, but neither of them were, in my opinion, given the attention they deserved. I mean, you know the story about how Andy did the dollar-sign paintings and Leo put them in—

BRANT: The basement.

GAGOSIAN: In the basement in his gallery on Greene Street. That was the last solo show Andy did with Leo.

BRANT: I remember that very well because those dollar-sign paintings were extremely radical at the time.

GAGOSIAN: Because they’re vulgar.

BRANT: And, in all fairness, Leo was always a very big supporter of Andy’s, but he was maybe unsure at that point. He wanted to support Andy, but he didn’t really know if he was doing the right thing.

GAGOSIAN: It pissed Andy off—I know, because he told me that it pissed him off. That’s when he stopped working with Leo. I mean, there are always two sides. But both Andy and Cy were very instinctive and made their own decisions. They were part of an art world that doesn’t really exist in the same way anymore. I miss those kinds of artists. They were two of the greatest artists of the century, in my opinion. But at one point, they were both kind of marginalized by Leo.

BRANT: How has the relationship between artists and galleries has changed? Do you think artists are looking for something different today out of representation?

GAGOSIAN: A lot of artists now are involved with fabrication. Artists today are making more objects and many of them need the participation of a dealer in order to facilitate and provide support for projects. So that has changed. But I don’t know if what it means to be an artist has really changed. I hope that it hasn’t.

BRANT: How do you balance your involvement with the business of being an artist and supporting projects and facilitating the work with your involvement in the business itself, which has changed so much?

GAGOSIAN: I think functioning as a business manager can be a hindrance to having a real dialogue with the artist. I do think that artists need good lawyers and accountants, because they’re dealing with serious money. But an artist who stands behind a manager? That’s a little different. I think that can be a bad buffer.

BRANT: You’re usually a big collector of work by artists that you represent. Does that feel seamless and comfortable for you?

GAGOSIAN: For me, it’s sort of a natural extension of being an art dealer, because if you don’t want to collect the artist, then you probably shouldn’t be representing them. I think it’s a pretty good test of your enthusiasm and commitment to go into an art studio and want to own something. I will say that it sometimes causes problems because another collector will say, “You’re keeping the best one.” That’s a valid criticism, but it doesn’t really bother me. I never buy more than one or two things in a year or two—and, honestly, I feel like I’m entitled. The artists usually don’t mind. They also know that if they need a piece for a show, then it’s there, and I’m certainly not going to put it up at auction. Collectors sometimes behave worse than dealers in terms of how they handle their collection.

BRANT: You also have a lot of work in your collection by artists that you’ve represented but who you no longer represent, correct?

GAGOSIAN: Sure. I like collecting.

BRANT: How many artists do you represent now?

GAGOSIAN: I don’t know.

BRANT: You don’t know what the number is?

GAGOSIAN: I mean, it’s not endless. There are other galleries that probably represent about the same number. You get to a point where you really can’t manage more artists, because representing artists takes a lot of time.

BRANT: You’ve developed what is now a global business with galleries all around the world. When did you decide you wanted to expand in that way and open up exhibition spaces in other countries?

GAGOSIAN: It wasn’t really a decision. I didn’t have that vision, so I can’t take credit for it. But I had a woman who worked for me named Mollie Brocklehurst. Mollie was from England and she worked here at 980 Madison, but one day she told me that she needed to move back to London. I was really bummed out because I liked her and she was really important to my business, so I said, “Why don’t we try to keep connected in some way? Maybe you could work for me part time out of your flat in London.” She was interested in staying in the art world, so she said, “Great.” We got a little office—Charles Saatchi gave us some space in one of his buildings. And then one day I said, “Well, let’s just get a gallery.” I wasn’t planning to have galleries all over the place. It was just like having the gallery in Chelsea. It was kind of happenstance.

BRANT: There was no plan.

GAGOSIAN: No. But I think what we’ve done with opening galleries around the world, which was really kind of a spur-of-the-moment decision, seems to have influenced other galleries and created more competition. People are following us, in a way. So I am proud of the fact that we had a hand in creating a model that other galleries are now adopting to varying degrees.

BRANT: Do you spend most of your time these days at 980 Madison?

GAGOSIAN: When I’m in New York. I have an office in Chelsea, but I never use it. I love the gallery uptown. I can walk there. It’s nice to be able to walk to work.

BRANT: So what, for you, are the priorities in your business as it grows?

GAGOSIAN: Professionally, what comes first is representing the artist.

BRANT: Whether they’re alive or they’re dead.

GAGOSIAN: Whether they’re alive or dead. Then the so-called “secondary market” has also always been something that I’m comfortable with. I’m not a dealer who turns his nose up at that part of the business. I’m an art dealer—my primary responsibility is to represent the artist. But I think artists like being in a gallery where there are a lot of other things going on. It creates more energy. That we’re dealing with classical art and all of these other things keeps my juices going.

BRANT: What do you think the future is for art fairs? They seem to have become a bigger part of how the art world functions now.

GAGOSIAN: I think they’re becoming more and more important. There are so many buyers now all over the world who don’t necessarily feel comfortable with the whole mechanism of buying art, and an art fair is more accessible. You go to an art fair to buy. It’s demystified. It’s very direct. I like art fairs.

BRANT: How many do you go to now?

GAGOSIAN: Probably eight or nine total. They’re very demanding. But Art Basel in Switzerland is still the big daddy of all the art fairs—at least for us.

BRANT: How do you feel about the marketing part of the art business and how that has developed?

GAGOSIAN: I’m involved in it—I’m an investor in Art.sy [the recently launched art website] with Dasha [Zhukova] and Wendi [Deng Murdoch]. I think it’s unproven, but I’m hopeful—I think that under certain price points, it will probably grow and be successful. Christie’s is doing a huge amount with the Warhol Foundation inventory. Photographs are also very well-suited for that kind of thing. But pieces where you have to really see and touch? Like I said, I’m hopeful, but I don’t really know. There are just so many more collectors now than when I was starting out. The pace was much slower. But now, with the electronic distribution of images, things move much more quickly.

BRANT: That reminds me of the great Jackson Pollock show in 1950 of drip paintings the year after he was featured in Life magazine. That show was not sold out. There weren’t as many collectors at that point, and a lot of the artists who came home after the war couldn’t sell their work.

GAGOSIAN: Jasper Johns couldn’t sell his stuff back then. But it’s a different world now. I know that you concentrate on American artists, but there are great artists all over the world right now. There are emerging economies in parts of the world where there should be collectors. We don’t do much right now in India, but I’m assuming at some point that will change. We do a lot of business in China-we have a gallery in Hong Kong. Latin America has also become more present in my business. Russia went through a little bit of a slump, but over the last 18 months they’ve come back. So I’m optimistic about art dealing in general. There are probably more interesting young artists around today than there have been since the 1960s.

BRANT: I’m very excited about what we’ve seen over the last five years. So many artists with real talent have emerged.

GAGOSIAN: I agree. We’re involved with quite a few younger artists, and it’s fun for me. Working with younger artists kind of tests your judgment. You’re not always right, but when you are, it’s exciting.

BRANT: So in terms of your life, you’re a collector, you’ve built your business in the art world, you socialize in the art world, you’re always dealing with artists, collectors, other dealers . . .

GAGOSIAN: Well, I enjoy it—I have a totally fun life. I come home and I don’t need to shift gears. It is all one and the same. But you know me—I like to have a good time. I don’t work 24/7. I like to relax. I’m capable of being with friends and not thinking about work. I know that I need to read for pleasure, play tennis, watch movies, have one too many drinks.

BRANT: Do you ever think about the role you play in the art world?

GAGOSIAN: Honestly, I don’t think of myself as having a role. I just do what I do. I think that everybody contributes. You don’t have to have 12 galleries to be a big contributor. My neurosis is that I’m driven to do that, but there are great people who have one or two galleries who contribute as much as I do.

BRANT: You’ve consistently done pretty well over the years—through good times and bad. But I’ve heard—as I’m sure you have—some people try to make excuses for why you do well, or who are critical of the impact that your success has had on the art world and on the market.

GAGOSIAN: I know what I’m doing, but I also understand where those people are coming from, and it doesn’t really bother me. The critical stuff mostly comes from colleagues-I don’t think collectors or museum people feel that way. But I can understand it. I’m kind of an outsider a little bit-or at least I was. I don’t think of myself as an outsider now, but given my set of circumstances, it’s not surprising. I’ve probably rubbed some people the wrong way. I was very aggressive and tried to be correct. But, you know, I play hard. So the critical stuff doesn’t surprise me or bother me. If everyone likes you, then you’re probably not doing much. If you say, “Oh, this is such a nice dealer,” then it probably means that he hasn’t sold a painting in the last couple years.

BRANT: So what advice would you give to someone who is just starting to collect?

GAGOSIAN: Head over to 980 Madison.

BRANT: That’s a good one. [both laugh] But as they walk over to 980 Madison, what should they be looking at or thinking about?

GAGOSIAN: I don’t think you can tell somebody how they should collect. It’s a question I get asked a lot, but I still haven’t come up with a good answer. I think it’s just about being turned on by art. At the end of the day, some people just kind of get it. They don’t all get it in the same way or get the same artists, but it’s a journey that excites them. I’ve had people say to me, “Well, how do I start?” Well, you start by buying. Buy what you like, buy what you can afford—and I’m not just saying that because I’m a dealer. You can’t be so paralyzed to where you keep saying, “I’ve got to learn more.” The best way to learn is to go home and actually put something on the wall. Then you’ve got an investment. Then you’re living with it. Then you’re in the game. But when a collector says, “You’ve got to educate me,” or “What’s a good investment?” then I don’t know what to say. I have no idea. Let’s face it, I’m probably going to recommend artists that I represent.

BRANT: You also buy artists who you don’t represent.

GAGOSIAN: Absolutely. But the way you educate yourself is by actually getting in there and starting to collect. And what if you make a mistake? In a way, there are no mistakes. If you buy something that you don’t like, then you sell it and move on.

BRANT: Larry, at this point you’ve spent most of your life doing this. You’ve built a great organization. You’ve represented great artists. You’ve built a personal collection that, in terms of postwar art, could probably match most museum collections. Do you ever think about what you’re going to do with it all or where it’s going to go ultimately? Do you ever think about your own legacy?

GAGOSIAN: I think about it a little bit, but I haven’t really come up with a plan. I don’t really know what’s down the road. I’m excited to drive out to Brooklyn now to have lunch with Urs Fischer—that’s what turns me on. I get up and I love doing things like that, just like anybody who enjoys their job. But as far as the big picture and what’s going to happen? Legacy schmegacy. I don’t know. I don’t get that legacy thing. It’s funny because there have been some great interviews in Interview over the years, but one that I’ve quoted many times is the interview that Henry Geldzahler did with Jean-Michel. I can’t quote it verbatim, but I think Henry said to Jean-Michel, “There is anger in your work, but there’s also humor.” And Basquiat said, “People laugh when you fall on your ass. What’s humor?” [both laugh] I thought that was kind of a great response. Jean-Michel said, “You don’t know how people are going to regard you.” Basquiat was probably 21 or 22 years old at the time, but how prescient the guy was to come up with an answer like that.

BRANT: You’re opening a restaurant now in the building that contains the uptown gallery.

GAGOSIAN: I see it as an amenity almost. It’s a place for people who are interested in art to gather. It’s going to be like an extension of the shop we used to have on the corner. We’re also going to have a gallery there where we’re going to do things with younger artists, and then you’ll go downstairs and the whole ground floor will be the restaurant.

BRANT: How many people will it seat?

GAGOSIAN: About 80 people. It will probably be open 10 a.m. to midnight. Annabelle Selldorf is doing the décor, so it’s going to be very cool. I think it’s the first time she has done a restaurant.

BRANT: So it will be modern.

GAGOSIAN: Very modern. But at night, it’ll be kind of moody.

BRANT: So it will also be a neighborhood restaurant.

GAGOSIAN: It will be a neighborhood restaurant. Bill Acquavella already reserved a table. He was one of the first to say, “I want to have my own table.” So that’s good news. We’re going to try to have it be a destination for people who like wine and try to get wine companies to bring us special wines. We’re going to have international cuisine. We’re going to have waffles for breakfast because I love the waffles at the Beverly Hills Hotel. I put some things on the menu that you can’t get in every restaurant, things that I like. I love chili, so we’ll have a good chili. We’ll have a couple of Armenian dishes. But we’re going to have fun with it. I could have done a menu by consensus, but so many people were telling me what to do that I finally said, “Screw it. This is what I want.” I just want to be able to go down there and have a good time and be able to entertain my friends.

BRANT: When will it open?

GAGOSIAN: Probably in February or March.

BRANT: So finally, I have to ask you: Is it true that you once had a pet snake?

GAGOSIAN: Yeah. A boa constrictor.

BRANT: I heard a story, though, about how you went to buy a snake?

GAGOSIAN: Well, I already had a boa constrictor, but I wanted to kind of up the ante. I wanted to get an anaconda. So I did some investigation, and there was a guy out in kind of a rough neighborhood who had an anaconda, so I went to go see it. The guy was living in a motel room, and I remember that he had the anaconda in the bathroom, and it was draped over the shower in the tub. This snake was so big that it came all the way over the shower into the tub. It was humongous. I’m sure it was illegal . . . I didn’t buy it—I was more scared of the guy, I think. [Brant laughs] But I actually drove out there to look at this snake. I’ll never forget it. So it’s a true story: the one about the guy who almost bought an anaconda.

Peter M. Brant is Interview’s chairman.