BLOB

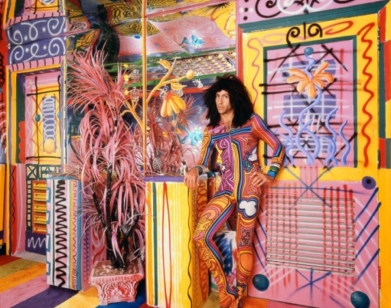

Kenny Scharf on Trash, Artificial Intelligence, and the Golden Days of New York

“When I was a young whippersnapper, there was no question—I had to be in New York,” says the 66-year-old artist Kenny Scharf. However, after rubbing shoulders with Keith Haring, Andy Warhol, and Jean-Michel Basquiat and establishing himself as a vanguard of the pop art movement, the L.A. native returned home. “I’m a California boy,” he confesses. “I like swimming and I like nature, I like my garden.” From his house in Culver City, Scharf can see the ocean. But last month, he could also see the wildfires that ravaged his beloved city. So when Equinox asked the legendary artist to design a limited edition t-shirt, with all of the proceeds going to the L.A. Fire Department, it was a no-brainer. To celebrate its release and the resiliency of Los Angeles, Scharf called up Shai Baitel, who curated the artist’s upcoming summer exhibit at the Modern Art Museum of Shanghai, to talk about just how much he loves L.A. (and, conversely, how much he hates AI-generated art). “I dislike it intensely,” Scharf exclaimed. “I can tell it’s devoid of anything as far as the soul goes.”

———

KENNY SCHARF: Are you in Europe?

SHAI BAITEL: Yeah, I’m in Europe and you’re in your beautiful studio. I miss you, Kenny. I haven’t seen you in two-and-a-half weeks.

SCHARF: I know. You have to come back.

BAITEL: I’m coming back and we’ll start our discussions over everything for Emotional, which is interesting, because I felt emotional speaking about the collaboration with Equinox, the reason for our gathering today, and raising funds for the L.A. fire efforts of rehabilitation and supporting the needy. So of course, a very emotional experience, which I would like for you to tell us more about from your perspective, and then we’ll talk about this very unique partnership with Equinox.

SCHARF: Well, that’s a lot of talking.

BAITEL: But we like that, so…

SCHARF: Where do you want to start?

BAITEL: I want to start with our meeting in your place a few weekends ago where you showed me how you watched with your eyes where two fires were spreading, and what went through your mind, and how scared you were, and how overwhelming it was.

SCHARF: Well, first, I want to say I’m very lucky and very grateful to be relatively unaffected. I just had to breathe the air and witness flames, but I didn’t have any damage. I didn’t lose anything, but it is and was a very sad time here in L.A. I have a view of all the way from Santa Monica, Palisades, all the way past Hollywood from my house, so I’ve witnessed these fires before. But this one was so big. And I’m lying in bed, my head is on the pillow, and I’m watching the flames five miles away, realizing that as the flames are moving up and down the mountainside, they must be 100-feet tall because I can see them that far away, just moving up and down. It’s just mind-boggling. And unfortunately, I don’t think it’s a surprise. I mean, it hadn’t rained in eight months, and they were like, “Oh, hurricane-force winds coming tonight,” the red-flag warning, and my first thought that night before was, “Well, it’s not a question of if. It’s a question of where. Where is the fire going to erupt because there’s going to be one?” So I’m happy to be able to do this collaboration to help so many people.

BAITEL: Speak about the artist community and about the fear for significant art, because this is a striving community that’s very supportive of one another, and many collections had to be packed quickly and put away into the mainland.

SCHARF: Well, I didn’t have to deal with it myself, but I think we will be hearing more and more in the coming days about different pieces of artwork that are loved and that are burnt. That’s a hard thing. What do you do, right?

BAITEL: Let’s talk about Blobz and this very unique image that we chose for the collaboration with Equinox. A lot of your work is a reflection of your signature iconic creatures, as we call them, that are populating your canvas. But this very specific work is more abstract. There is fluidity, there is movement, there is overwhelming emotion with the various colors. There is the feeling of your hand through the brushstroke, and you’re one of the very few [artists] that insists on painting on your own without any assistant, without any apprentices, which is incredible. Every time I come visit you in your studio, I see you dancing on the canvas, bringing all your livelihood into this magnificent visual language.

SCHARF: Thank you. Well, I’ve been doing Blob paintings for decades, inspired initially by surrealism and biomorphic surrealism, artists like [Yves] Tanguy and Hans Arp, and creating forms in your head that don’t exist in real life. But giving it form, giving it light and shadow, and being able to visualize something by making it look three-dimensional is something that is kind of part of my practice, taking imaginary things and making it look like you could reach out and feel it. So the Blobs, there’s very different kinds of them. There’s the Blobs, which are on the T-shirt, which are just shapes and emotions all interlocked together, squeezing out any pictorial distance. They’re right at the surface, and they’re kind of overflowing and taking up all the space. In these Blob paintings, often I have them with eyeballs and expressions, very cartoonish faces on them, but really, they’re all the same whether they have eyeballs or not. In a way, it’s a little bit of an analogy in that we all are here together and we’re all different, different colors, different shapes, but we all are taking up this space together. It’s a kind of coexistence, in a way.

BAITEL: And I have to admit that in our research as part of our preparation for your retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in Shanghai coming up at the end of June, we looked at some of the abstract versus the more explicit works, and we found this magnificent similarity in energy, in movement, in this specific pace that only you know how to create—almost to suggest that even in the abstract you could come in and insert whatever you would like to make them a little more recognizable. But if needed, it will still be recognized as part of your own unique language.

SCHARF: Exactly. It’s not necessary. It’s just whether I’m in the mood or not.

BAITEL: I had these conversations with you about who your art belongs to, and I love the idea that you have canvases and you have limited editions and that you have so much merch. You really allow for the art to belong to everybody. There is something incredibly important and sophisticated in the dissemination of your genius that is not tacky and cheap.

SCHARF: Well, thank you. And really, I’m glad that you feel that, and I think the reason is because it’s part of my whole philosophy as an artist. I’m not changing my stance and my philosophy one bit at all to do some kind of a mass market object or piece of art. It’s always about inspiring the masses, making art accessible, and living in the same place as appealing to a more elitist art audience. So I believe that you don’t have to exclude the common public who maybe doesn’t have a knowledge about art history. I want to appeal to everyone, but on different levels. Also, my imagery is in so many ways coming from the mass market of my childhood and the imagery that I grew up with that became part of my subconscious imagery, so it just naturally lends itself to going back into that system where a lot of the images came from.

BAITEL: Kenny, when I spoke with Equinox and suggested you for the collaboration, I told them there is a wealth of shared DNA. It’s not only about your work at Equinox that looks good, feels good, but also the idea that you were born in California but traveled to New York to study, and you returned to L.A. because this is a place where you felt there was more light and more reason for your art-making. It’s also the same philosophy of Equinox, of course, that allows you this optimism and hopefulness, which we find in great quantities in your work.

SCHARF: Well, I feel like some of my work maybe looks more on the surface at dark things, but on the whole I like to bring the visual element of joy and optimism and light and fun because I think there’s so much darkness. I feel it’s almost important to keep the optimism going no matter what. And that’s not for my audience, but I’m glad my audience identifies with that. In order to keep myself going, I have to be optimistic, whether I should be or not.

BAITEL: You graduated in New York in 1980 from The School of Visual Art, and you have lived through a historic time in the world and more specifically in the art world. And during this time of the East Village blossoming with creativity, it was you and Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith [Haring] and [Andy] Warhol. You are like the last of the Mohicans, because the rest of them are gone. What has changed between the heyday of New York art and today?

SCHARF: Well, I’d say the biggest change, and that’s not just for New York, is the World Wide Web. Back in those days, you really had to be there physically. You had to be living in New York amongst this group and being in person and having that time and the audience to inspire each other. And now, I guess you could be living anywhere and doing something and, all of a sudden, everyone sees it, albeit on a small screen or on your phone. So the reach is great and it’s changed everything, but at the same time, the urgency to be in proximity to other fellow creators—well, I think the urgency is there, but it doesn’t have the same center and place that it used to, and that’s changed a lot.

BAITEL: Do you feel that the artist’s mission has changed because the times are changing? Did you think that back then there was solidarity? Is it still there?

SCHARF: Well, I like to think that there’s an artist’s camaraderie. Whether or not there still is, I still believe in it. And then when I encounter the opposite, it’s a little bit maddening, but then I just go on thinking that artists support each other. Artists can be very competitive, and that’s the thing I don’t like. I think there’s enough room for everyone, and there’s enough audience. This idea of scarcity and hoarding, this is so wrong and it doesn’t need to exist in the art world or, of course, in the world itself. I’m not very excited about AI and art. In fact, I dislike it intensely, I hate the way it looks. For me, art is about emotion and humanity and a real touch, and the further we go into technology and AI, the further away we go from art that is emotional. I see AI art and immediately it kind of makes me feel sick inside because I can tell it’s devoid of anything as far as the soul goes.

BAITEL: I agree. When we started our dialogue over two years ago, I told you that I am incredibly impressed with the way you capture emotions in your artwork. And the more I delved into the work and studied it and learned more, it dawned on me that you have given us the original emoticons. What we use today so frequently, so flawlessly, so naturally, you actually were the prophet. You were the one that gave it to us, first in subway stations and wherever you found that urban canvas, you started putting them out there. Fast-forward with this new technology, the first thing people do after they update their iOS is they go to see the new emojis, which is crazy. [Scharf’s cat enters the frame] Oh, look at this kitty.

SCHARF: I brought her to the studio.

BAITEL: She’s so curious.

SCHARF: She loves it.

BAITEL: So we decided to call your show at the Modern Art Museum in Shanghai at the end of June 2025 “Emotional.” The fourth floor of the museum will be designed and called the Kenny Scharf Beach Club, and we will bring the whole Los Angeles Venice Beach vibe, where we are planning to place, say, five gigantic sculptures of yours, which are actually the originals from Luna Luna. What I’ve also realized is that you really like to paint and to spray on objects from cars to skateboards to surfboards. Tell us more about your obsession with collecting trash and debris and turning them into objects of art and celebrations of color and shape.

SCHARF: I’m obsessed with garbage, trash. When I moved to New York in the late ’70s, New York had a lot of it everywhere, so I am always looking. And I find that our garbage really reflects our society in so many ways. It reveals so much, and I’m attracted to that. I’m also attracted to the discarded, the no-longer-wanted, the thing that can be reborn and given a new life—that appeals to me. I started collecting these objects. Well, first of all, back in the early days in the East Village, everything was from the garbage. We would get our furniture from the street, chairs and dressers; maybe not mattresses, but almost everything was furnished from what you found on the street. And then our fashion, all those ’50s suits that you see, it was because those were left over from the ’50s. We would find these shark skin suits in the garbage, leopard skin housecoats, and turn them into our fashion. Everything was about looking at garbage and using it and reusing it.

BAITEL: The art-making of it is spontaneous. And you also work with items we don’t use anymore, like a landline telephone or—

SCHARF: Answering machines, yeah.

BAITEL: You’re bringing a lot of those archaic elements into your work in a way that makes them relevant again. That’s another achievement of yours.

SCHARF: Well, thank you. I mean, they were not archaic at the time. They were my actual appliances. It was telling a story back then, and now it tells a bigger story, not only about the moment when they were new, but now looking back you see these objects that we don’t have anymore, they’re obsolete. They have this aspect of performance art in them because they were used. Part of regular life became a performance.

BAITEL: Which is more inspiring to you, New York City or Los Angeles?

SCHARF: When I was a young whippersnapper, there was no question—I had to be in New York. I know there was a lot of art going on here in L.A,, but as a young person, I had no idea, I had no connection to it, so I just wanted to get out of L.A. For me, it was like a big suburb and I wanted to be in the city, a real city. L.A. never felt like a real city, although it’s becoming one. And now I’m not such a young whippersnapper. I grew up in L.A. and I’m a California boy. I like swimming and I like nature, I like my garden, I like the ocean, so these things are really important. So as I got older, I realized, “Eh, I think I need to go back to L.A.”

BAITEL: Well, age is energy, and you’re young in every possible way.

SCHARF: Thank you.

BAITEL: You have two daughters and grandchildren, which are bringing a lot of joy to your life. How are they participating in the creative process for you?

SCHARF: Well, my kids and now my grandkids are creative individuals. That’s how they grew up. I think my grandkids are starting to realize that not everybody has the kind of environment that I provided for them and that my kids are providing for them now. It’s just so important to be creative. What else is there? I mean, love and creativity and nature—

BAITEL: It’s so important. Kenny, you’re one of the most collaborative artists that I know, and you collaborate in a very stylish way, from Dior to Samsonite. I know that it’s asking who’s your favorite kid, but which is the one that you like most?

SCHARF: Well, I mean, the Dior one was pretty damn good. What I loved about it was the way Kim Jones, the designer of Dior, felt really respected by him, how he took my imagery and used it. I don’t think I’m allowed to announce it, but my latest collaboration is a really big one to me because it was kind of like a childhood dream. If I’d been told that I was doing this collaboration as a child, I would’ve gone to heaven right then and there. But I don’t think I’m allowed to mention it.

BAITEL: Last question, Kenny. There’s an iconic picture that Patrick McMullan took in ’86. You’re on one side, Warhol in the middle, and Keith on the other side. So tell the readers of Interview, what did you learn from your peers?

SCHARF: Well, let me just say, Andy Warhol wasn’t a peer. He was more of a hero or mentor. He was 20 years older than us, and you can talk to thousands of artists who moved to New York when I did and almost everyone was like, “Oh, Andy Warhol.” Everybody moved to New York because of Andy Warhol. Andy Warhol was this almost godlike to me and to everyone, Keith and Jean, so many of us artists. He wasn’t a peer because he was way above me, so I just want to say that.

Kenny Scharf is on view at The Brant Foundation’s New York space through February 28th. 421 East 6th Street, New York, NY 10009.