Joseph Kosuth Digs Deep Under the Surface of Culture

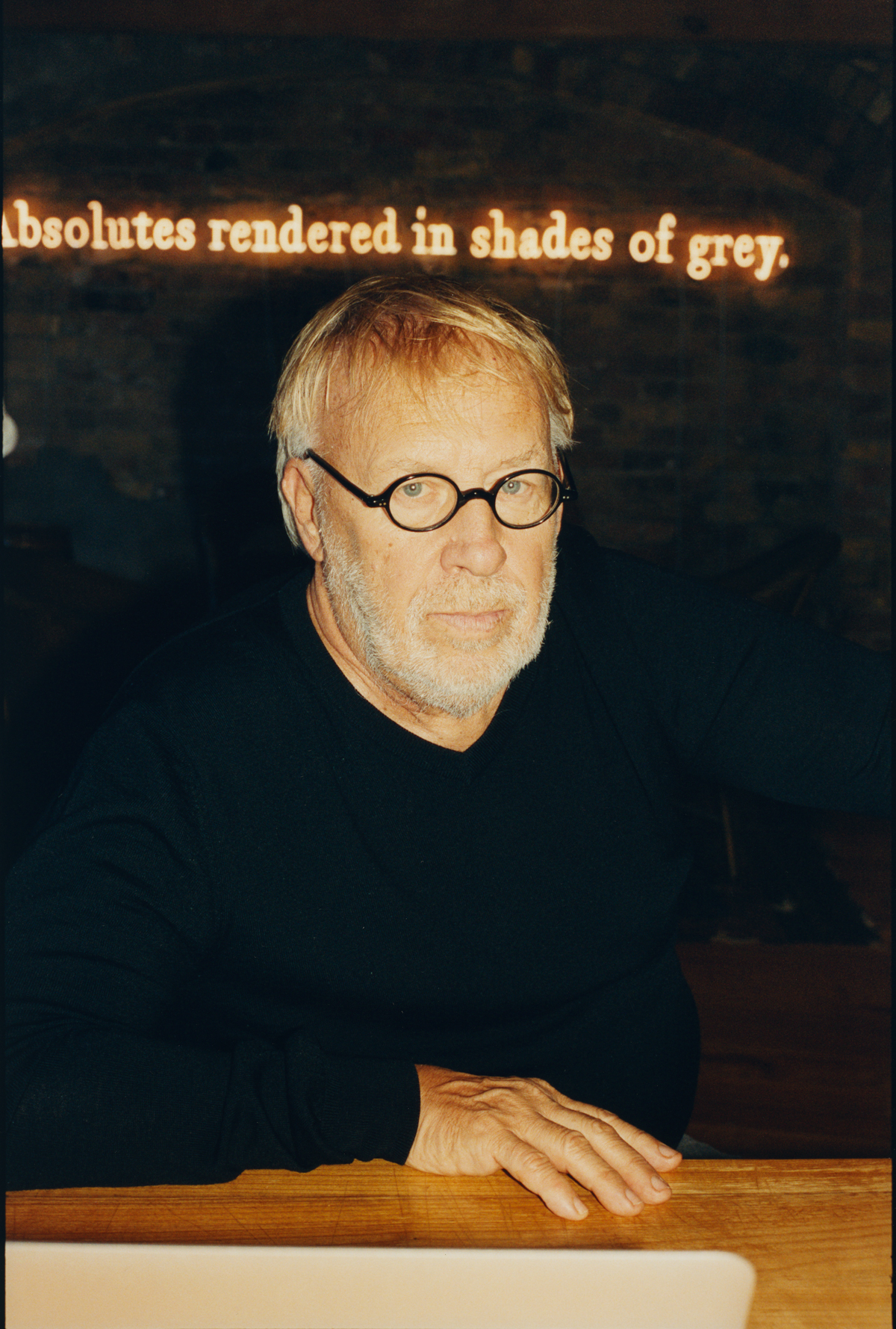

I can’t say I wasn’t nervous about meeting Joseph Kosuth. Any time I’m asked who my influences are, my immediate response (among a few other music and art icons) is him. But on the October morning that I went to interview the 73-year-old American artist at his studio in South London, I realized that that has been a lazy answer. I know next to nothing about Joseph Kosuth. Well, I know some of the famous works, such as his 1965 piece “Clock (One and Five),” with its ice-cold analysis of object as time and time as language. I know his much-copied “Five Words in Blue Neon,” whose primary purpose is to describe nothing beyond itself. And I remember as a graphic-design student in the early 1990s being thrilled by his work on billboards—real art on real billboards on real streets. I also know, though don’t fully understand, the foundation of his thinking, informed as much by Ludwig Wittgenstein as it is by Marcel Duchamp. I particularly know how much “One and Three Chairs”—a work from 1965 constructed from the “re-presentation” of an actual chair, a photograph of that chair, and the dictionary definition of “chair”—impacted me all those years ago at college.

So, yes, I was nervous—nervous enough to print out Kosuth’s seminal 1969 essay “Art After Philosophy” at six that morning. Was I really going to digest it before I set off to his studio three hours later? Of course not. But I got the basic idea.

———

SCOTT KING: My brief from Interview was to not make our conversation too art-speak.

JOSEPH KOSUTH: Don’t worry, I don’t talk like that. And I know the publication well. Andy interviewed me a long time ago. We were at the Palace Hotel on Christmas Eve with our mutual dealer Bruno Bischofberger. It was a fairly big dinner. Andy was across from me and he said, “Can I interview you for Interview?” I had drunk quite a bit of Kir and cautiously said, “Sure!” Mostly Andy asked about my sex life.

KING: My questions will probably be dull compared to Andy’s.

KOSUTH: It wasn’t in the brief for you to ask me about my sex life?

KING: No, but if you want we can talk about that.

KOSUTH: It’s not desire that’s diminished, it’s opportunity.

KING: Tell me about it! But, actually, I wanted to start by asking you about the cultural landscape in which your art first got recognized. I’m thinking particularly about mid-’60s America—with Motown, Vietnam, Fordism, pop art. Can you paint me a picture of the period in which you became a butterfly?

KOSUTH: A butterfly. Well, I was really young, but I was keeping my age a secret, knowing I wouldn’t be taken seriously. That’s kind of an important thing to know. I had a lot of shows really young—like 23 solo shows before I was 25. I started teaching at university when I was 25—if art school can be called university. I’m kind of a wrinkled wunderkind.

“One and Three Chairs,” 1965, is a work from Kosuth’s Proinvestigations series, which utilizes deadpan ‘scientific style’ photographs that are always taken by someone other than the artist himself, and which employs common objects and enlarged texts from dictionary definitions. The artist’s intention is to eliminate the aura of traditional art and instead create a “conceptual” approach. Photograph courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery New York .

KING: The residue of a wunderkind.

KOSUTH: Well, they do get old. There was buzz about my work in the art world. I remember I first met Andy at the opening of a Dan Flavin show at Kornblee Gallery. Somebody tapped me on the shoulder, and I turned around and it was Andy Warhol asking for my autograph. “Oh, my god,” I said to myself. Then he asked if he could do my portrait, and that we should do a trade. Which he did. It’s a very nice thing, art for art. Artists were the ones with the responsibility, and the very essence of their activity was to be makers of meaning. Artists don’t work with forms and colors. We work with meaning, and we employ what we need to in order to construct that meaning. I was fighting for a certain idea of art. It wasn’t about career ambition.

KING: What were the spaces that showed your work?

KOSUTH: When I was 24, I went to the Leo Castelli gallery, which was quite something. I was a little nervous about going to a place that was such an institution, but I felt most people wanted to ignore conceptual art. The market wanted big, colorful paintings. It didn’t want little things on pushpins or video or whatever was going on. So I went there with the idea that it would give the art a chance to flourish.

KING: So you saw Castelli as a platform to introduce that language on a wider scale than just a small New York clique.

KOSUTH: It had to be taken seriously and historically, which was the only thing I was thinking about. I never imagined it was something I’d make money from. The art world was a much smaller place. It didn’t have this massive corporate presence we’re now stuck with.

KING: It’s the difference between art and the business of art.

KOSUTH: They’re quite different things. My major works, which I think I can say pretty unpretentiously had a major art-historical effect, sell for a small fraction of what a totally derivative, half-conceptual painting by some kid, three years out of high school, would sell for. It’s quite funny, really.

“A Monument of Mines,” 2015. This permanent installation connects modern architectural expression with the region’s former position as a center of Norwegian silver mining. The installation consists of 136 neon elements with silver leaf installed throughout the building’s six-story atrium. Each neon panel details the name and closure date of the silver mines which were once active in Kongsberg, simultaneously presenting a tribute to the mines and the region’s history. Photograph courtesy Galleri Brandstrup.

KING: Well, fortunately, Joseph, or unfortunately, you’ve almost answered all of my questions in one go there! So I could go home now, but picking up on what you said there, I have a theory. It’s more of a conclusion. I’ve concluded that a commercially successful work of art relies on, one, being attractive—like a flower is to a bumblebee. And two, it has to contain a minor puzzle. This minor puzzle is easily explained by gallerists to the potential collector.

KOSUTH: That’s a really depressing scenario you’re describing.

KING: But I’m asking, is there any truth in that? I’m talking not about your work but the opposite: work for art fairs and Instagram. I feel like there is a level of work where galleries cannot wait to tell the potential collector, “Oh, this yellow is the same yellow that his granddad used on his shed door.” Everything seems to contain this minor unnecessary puzzle. Am I correct, or am I just making this up?

KOSUTH: My belief is there was never a dumb artist who became important. Whatever theoretical presumptions the work has, there’s always this fear that the artist has somehow lost touch with their humanity. So by bringing in their grandfather’s yellow barn door, they give a kind of folksy connection to something concrete beyond color theory or whatever else it might really be about.

KING: So it becomes again a signifier of humanity so that people can make sense of it.

KOSUTH: Something along those lines. But the art market is a continual dumbing down of art history in a way. I used to wonder why Duchamp, who was truly a major artist, sells for almost nothing while Picasso has these big prices. Well, a busy billionaire simply doesn’t have time to learn about art history. So they want to know who’s the best. And who is the best? Well, the most expensive.

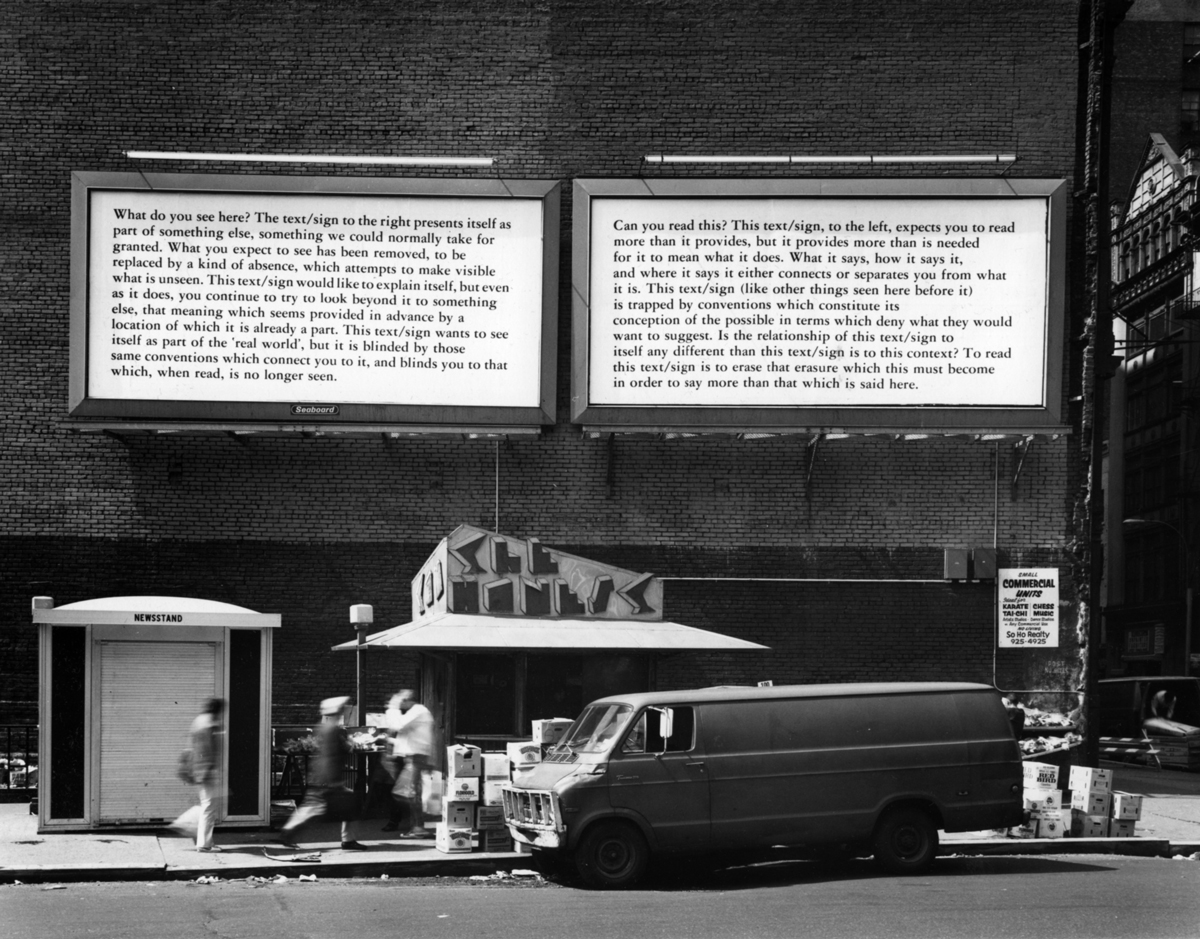

“Text/Context,” 1979 is a billboard work presented in cities in Europe, the United States and Canada. The paragraphs were written by the artist and intended to be read in two public contexts: the street and the art context (i.e. museum or gallery). The texts were first presented anonymously on the street and framed by their advertising context. After about a month, these billboards were then used as wallpaper in a museum or gallery. The texts were written to make apparent the cultural context upon which they were dependent for their meaning. Photo: Joseph Kosuth Studio / Courtesy of Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, U.S.A.

KING: What about showing at Leo Castelli?

KOSUTH: I was spoiled. That’s where every hero of mine showed. My first major collector was Count Giuseppe Panza di Biumo. He would go to his den after dinner every night and read about art for three hours so that he’d understand the work he was buying, in that really wonderful, responsible European way. It was like this other collector of mine whose name was Baron Giorgio Franchetti, the brother-in-law of Cy Twombly. He had this Disneyland-esque castle in the Dolomites. He’d have 20 house guests at a time. And I would watch this aristocrat walking around his castle, picking up ice cream wrappers and empty cups and things. He had this aristocratic sense of responsibility, this stewardship to take care of what he had in his lifetime. That’s not the same as having the most expensive Rolex so everybody thinks you’re rich. That’s the bourgeois point of view. I’m aristocratic on my father’s side, so maybe I already have a bit of prejudice.

KING: The simplification would be that the Wall Street banker is buying the work as an investment or to flip it.

KOSUTH: My collectors are ones who usually know a lot about art, that’s why they like my work. They see that it’s relevant. It’s not because it looks pretty, because it rarely ever has. I mean, I know what I’m doing. How it looks fits what it’s trying to do, you know? It’s not meant to have a snappy look that the market will like.

KING: When I first saw your work, I was at college in 1992. I was 22. I did graphic design. When I saw “One and Three Chairs,” I was blown away. I thought, “This is incredible. I want to try to design something like that.” But it demands so much. I get what you’re saying about how a certain amount of inquisitiveness would be needed in order to get your work.

KOSUTH: What’s interesting, though, is how conceptual art actually began to be influential. There are a lot of kids doing knock-off versions of my work, but have no idea that they are, because certain kinds of thinking leads you to certain kinds of solutions. I was just there some decades before. I’m fine with that. That’s how artistry works.

KING: They’re tapping into philosophical ideas that you’ve previously engaged with? Or are you thinking about how they’ve nicked the neon?

KOSUTH: This is one of the things one has to understand: Modernism was really about the limits of the medium. It was essentially a continuum, so artists were always described in terms of painting, sculpture, lithography, whatever—it was all about “how.” What I feel my work introduced—or conceptual art in general—was a shift from “how” to “why.” I ask what it means. How do we make meaning in culture? For the artist to be responsible, they have to understand the meaning they’re making in the world. One of the great contributions of conceptual art, which I’ve yet to really see acknowledged, is that the model of the artist was always previously the kind of male, Christ-like, witch doctor–like figure who made magical splashes on the canvas. Well, how could some painter, who’s a woman, compete with what is inherently a stacked deck against her? What work like mine did was level the playing field. It didn’t matter what your gender was. It was about the power of your work and the history of ideas. Since then, more and more important artists have been women, and the men have had to struggle to keep up.

KING: The heroic, Byronesque model of the artist was so prevalent in abstract expressionism. Do you feel like conceptual art was a direct reaction against that? Was it a conscious decision, or was that just how it worked out?

KOSUTH: Remember, this was the art of the late ’60s. I was actively against the Vietnam War when I was doing this work. My generation—or context, or whatever form of entity we would give whatever it is I came from—was suspicious of anything that brought with it authority. Whether it was the authority of the powers of society, or the authority of the idea that art had to be painting or sculpture—I was throwing all that out.

“Ex Libris, J.-F. Champollion (Figeac),” 1991. This public work is the result of a commission by the Minister for Culture of France. It is located in the town square of Figeac near the home of the renowned Egyptologist, Jean-François Champollion, who deciphered the Rosetta Stone hieroglyphs. Kosuth appropriated the Rosetta stone, reproducing a greatly enlarged version and installed it as a flight of stairs between the upper and lower levels of the town. The passage across the stairs is a parallel of the process decoding the three languages of the Rosetta stone. Photograph by Florian Kleinefenn / Courtesy of the artist.

KING: Now that you’ve put it like that, it’s very easy to imagine a parallel between refusing to be drafted and denying them product. You could argue that conceptual art is almost denying the authorities the products they so desire.

KOSUTH: The art market was rather alarmed by conceptual art. That’s why I had to go to Castelli. Otherwise, they could have just ignored us, the way Fluxus was, in a way, dismissed. Even today’s art teachers and universities aren’t accurate in their history of conceptual art. But even with their often-misguided influence, I believe in art and I know that the power of better work will outdo lesser work, even with the power of our critics behind it. It’s a waiting game.

KING: Here’s a question that might seem trite but is important to me. Do you like your own work?

KOSUTH: Oh, I love it. I make it because I don’t see it anywhere else. Artists aren’t art lovers. I don’t love everything. I had lunch yesterday with two collectors of mine and I realized they like all kinds of things. I can appreciate Matisse, but I don’t really like it. For me it’s all color and form and a prescription for art that I have really never believed in. I’m the same way about art theory. I support all kinds of contradictory theoretical entities and I have no problem with it.

KING: What about the series you did involving cartoon strips? You did a show back in 1993 at the Margo Leavin Gallery in Los Angeles where you put them in windows.

KOSUTH: I took cartoons such as Blondie, Wizard of Id, whatever, and I blew them up and silk-screened them on laminated glass with neon in L.A. Then with that are quotes by [Gottfried Wilhelm] Leibniz and [Søren] Kierkegaard. I spent a long time putting together the right cartoon with the right philosopher. But when I had this show, the traffic in L.A. was terrible and I arrived in the middle of my opening. These Hollywood lawyers, who were collectors of mine, came running over and said, “Joseph, did you get permission to use these cartoons?” Keep in mind that this was 30 years before Jeff Koons. And I said, “No, no, I didn’t. And I didn’t get permission from Kierkegaard either.” And they said, “Yes, but you can’t just take it and use it.” This was before we had a word called “appropriation.” I pointed to the cartoon and I said, “That’s not my work.” And then I pointed to the quote and I said, “That’s not my work either. Those are props. My work is the gap between the two. It’s the surplus meaning that goes together to create.”

KING: There is a literal gap between the image and the text. But does it turn into meaning in the mind of the viewer?

KOSUTH: Depending on what they bring to it, intellectual and otherwise. And as I say, I’m not in the donut business—I’m in the donut hole business.

KING: Have you trademarked that? You need a t-shirt with that on it. What do you think about the art world’s embracing of Instagram? Art now seems made to be shown on Instagram. I feel like it goes back to what you were saying before about this kind of marketable art—big, bright, simplistic. Is it hot or is it not?

KOSUTH: I first experienced Instagram from my daughters. For my last show at Sean Kelly, I did an installation involving my whole history of neon use. Sean told me that the gallery had 30 to 50 people, mostly women in their late teens and twenties, taking selfies in front of the neons every day. They’re not collectors. It’s success on another level. I have no problem with that.

KING: I guess when you look at any work in a museum over the centuries, it’s all based on the problematizing relationship to the current social morays and perspectives of the time.

KOSUTH: I did a big show at the Louvre, and the director said, “I’m getting inundated with requests to make your show permanent.” And they did. But the other curators, specialists in all the various nooks and crannies of art history, hated it. They didn’t want contemporary art in the Louvre. But I kept pointing out that the Louvre is a museum of contemporary art of different times. As some wag once said, all art is contemporary when it’s made.

KING: What’s your take on public sculpture? Because it seems to me there’s an awful lot of terrible, terrible—

KOSUTH: I made a national monument in honor of [Jean-François] Champollion, who decoded the Rosetta Stone. That was in the town of Figeac, where Champollion grew up. I went there and the house of the Champollion family was there and around it were a lot of houses that were falling apart. So we razed those. I wouldn’t want to be part of tearing down old buildings, but in this case they really were falling apart. And it did work there. The piece works as a bridge connecting two parts of the town—which was a perfect metaphor for the whole thing, of the communication of the Rosetta Stone and how it really linked the modern with the ancient. I got a key to the province for it. And a postage stamp in my honor!

“Neon,” 1965, adapted an existing form of public writing—neon signage from the street—to construct a work that avoided any associations to previous art mediums. Kosuth was one of the first artists to employ neon as a material for an artwork. Photograph by Marc Domage / Courtesy collection of the artist.

KING: My goodness, you’re a superhero in France.

KOSUTH: France has been very affectionate to me. I hope it keeps up.

KING: I feel like for a public sculpture, particularly here in London, you can sort of imagine the meeting that took place about it and all of the business of funding that went into it. You can imagine how it was sold to everyone and the bending of the artist’s idea that was required.

KOSUTH: I cringe when I hear the word “sculpture.” Sculpture is just an object with Kant in it. Take out the Kant and you have an art object. So don’t call every object a sculpture in my presence.

KING: Okay.

KOSUTH: The reader should note that I’m smiling.

KING: Do you ever have moments when you just think, “Fuck it. I’m just going to draw some huge cocks on a canvas”?

KOSUTH: Maybe when I’ve had too many whiskeys and start drawing on a dinner napkin, but otherwise no.

KING: What really pisses you off? And I don’t want you to say Donald Trump.

KOSUTH: I wouldn’t give him any more ink. But let me see. Maybe it’s because I’m American that I say this, but the influence of an American kind of thinking is more prevalent than it used to be. The two most powerful groups in our society are politicians, obviously, and businessmen—and women—but mostly men. And they are totally committed to their activity of short-term goals. Politicians want to keep the power, whatever the form of political system it is. Businessmen and businesswomen want to make money at the end of the day. And these are, by nature, short-term goals. Intellectuals—artists, philosophers, novelists, the people who make culture—make the long threads in the textile of society. We give stability to society. But those other two groups are the ones who promote themselves as the responsible adults, when in fact they make horrible decisions due to their commitment to short-term goals. The environment is the perfect example of this. Very few in those groups have acknowledged what’s going on and how serious it is. That pisses me off. And it pisses me off when people think artists are wild and irresponsible because their hair is a mess. Well, their thinking isn’t. The intellectuals have to be seen as the responsible members of society who tolerate and give joy to the extremely boring activity of businesspeople and politicians. And we should be recognized for that public service.

KING: Excellent.

KOSUTH: Note to the reader: He’s still smiling.

———

Photography Assistant: Thomas Carla