Jordan Wolfson

THIS IS WHAT GETS ME EXCITED BY THE PROCESS OF MAKING ART. IT’S HOW UNRELATED ELEMENTS GET FUSED.” -JORDAN WOLFSON

At a solo show at REDCAT Gallery in Los Angeles this December, New York-based artist Jordan Wolfson will unveil his latest boiling digital stew of shock, stock, and poignancy. Titled Raspberry Poser, the multilayered, multiform video includes animations of a heart-filled condom, a throbbing HIV organism, a cartoon of a malevolent red-haired child, archival interior shots of children’s bedrooms, footage of the sidewalks of London’s Soho, and Wolfson himself dressed as a clichéd punk wandering around gardens of Paris (and at one point even dropping his pants). Certainly, Wolfson is more inspired by surrealism than minimalism, but his antic appropriation confections manage to sidestep the overwrought and overindulgent. They are mesmerizing lyrical productions that push boundaries by borrowing cultural artifacts and reassigning them with new, Frankenstein-like possibilities.

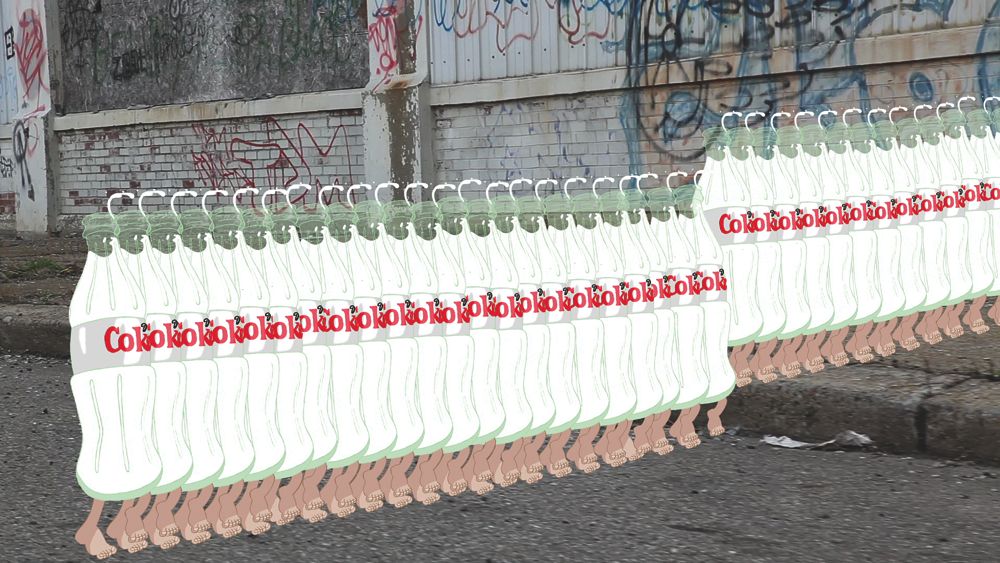

Wolfson’s films—and, to some extent, even his recent lobster-claw sculptural work, where full-frontal male porn is sealed over the claws—are like 21st-century versions of a Robert Rauschenberg “Combine,” created by a dirtier mind and a team of professional animators. (Or like going to an amusement park on a 10th date while on heavy hallucinogens—there is something perversely intimate, almost heartbreaking, about Wolfson’s mentions of love and loneliness woven into his spectral clips.) Wolfson first gained wide notice for his 22-minute 2009 animation Con Leche, in which cartoons of milk-filled Diet Coke bottles march around abandoned Detroit sidewalks to the soundtrack of a female actress reading text from Internet queries such as “How do I know I’m gay?” or “Why don’t I have any black friends?” or “Kate Moss cocaine.” Wolfson’s 2011 video Animation, masks is an unnerving odyssey in cartoon stereotypes and the limits of personal communication, as a CGI-animated caricature of a Jewish man (skinny-arms, thick-body, long beard, big nose, balding with a yarmulke) sits in disparate urban environments reading a copy of French Vogue while lip-synching, among other dialogue, a conversation between a man and a woman about what they like physically about each other. It is a disservice to Wolfson’s work to pull out just one scene or one ingredient—it’s how they blend and fuse and sometimes clash that really demonstrates his finesse and control of his corroded pop-cultural symphony.

Artist Helen Marten, who also appears in this issue’s portfolio of London artists, spoke with Wolfson about his videos and what he’s trying to achieve somewhere in the flurry of it all. -Christopher Bollen

HELEN MARTEN: I want to know something about boredom or banality and maybe a little about the hallucinogenic experience that can stem from it. I’m thinking in particular about your Con Leche video: The audience is watching a low-to-the-ground, street-level scene, where the view is limited. But then overlaid are your marching Diet Coke milk bottles.

JORDAN WOLFSON: The work really isn’t about the specific content to me. As I’m putting things together, it’s more about consistencies in form. When I went to Detroit to shoot the street scenes for Con Leche, at first I thought I’d show the city through landmarks and locations. But driving around with a location scout, I felt that the majority of locations that interested me were abandoned factories and warehouses that were mostly in ruin and covered in graffiti. Since the footage was going to be paired with a hand-drawn cartoon of Diet Coke bottles filled with milk, it occurred to me that graffiti is another type of hand drawing, so I could combine the cartoon with the graffiti. This is what gets me excited by the process of making art. It’s how unrelated elements get fused, which is a formal process. The content is the easy part. Putting it together in a way that’s cohesive is the challenge.

MARTEN: There is a build-up of disparate resolutions in your videos-hi-def CGI on top of grainy video. In spending time with your work, I’ve found that there is something quite sinister about what you do—and I don’t mean spooky. It’s more like a soft perversion. Your video Animation, masks is probably the most tangible example. What we’re looking at is “the Jew”—very human but also not.

WOLFSON: That’s funny. I never thought of what I do as sinister or perverse. I don’t really stop myself or reflect on the way things are coming out. But at the same time, I try not to indulge myself. In terms of the character, yes, I wanted him to be nearly human. The original character comes from an anonymous drawing I found when I googled “evil Jew” or “Shylock.” When I brought the drawing to the animators, I asked them to try for the look and emotional appeal of, for example, Shrek. When I first saw the finished character, I thought it was too much. But then I realized that, yes, this is how animation looks today.

MARTEN: He’s totally of our flesh—human hands, human eyes, human face. But there’s this ectoplasmic-like goo within his skin. He is the very image of a universal cliché, even down to the yarmulke, but then he’s sitting there reading Vogue. Another example is the Diet Coke bottle—this universal object of branding and advertising. But this bottle is walking around filled with milk! The whole sum is a stylization of wrongness or error.

WOLFSON: That is what I wanted.

MARTEN: You make actual objects too—sculptures, like your porno lobster claws. How are those made?

WOLFSON: Those are real lobster claws, and the pictures come from online searches for homoerotic images. I was specifically interested in images where the men were looking into the camera. I clean the claws really well and take them to a company that specializes in wrapping decal images on cars. They print out the images on special adhesive paper that is heated and then stretched over the top of the claws.

MARTEN: Are these related to the video works?

WOLFSON: It’s the same thing, really. In this case, the idea for the claws came directly from one scene in Animation, masks, where images flash over the character’s face like they are covering it. But in terms of actually making those sculptures, I got nervous about what I really wanted to do, and then I said to myself, “Well, you’re an artist; you should really just do exactly what you want to do.”

MARTEN: Those lobster claws are glib kinds of surrealist collages, but, just like the videos, they are sealed punctuations. The imagery is obscene, blatant, but the tactile pleasure of sex has been stripped out.

WOLFSON: I’m just making all of these things. But it’s funny because people will assume that I’m gay or that I’m secretly gay or that I hate being Jewish or that I’m seriously Jewish or this and that . . . [laughs] I’m always wrong about people’s reactions.

MARTEN: When you are researching, do you look a lot at books? Or are you more digitally minded?

WOLFSON: I do most of my research online, but I also seek out books and spend time in library picture collections. A lot of the still imagery in Animation, masks and the new video were sourced this way. Like, for example, the images of kids’ bedrooms in Raspberry Poser. In the new video, both the animated heart-filled condom and HIV virus float between still images of kids’ bedrooms, Caravaggio paintings, and live footage from Soho and Paris.

MARTEN: Tell me about the condom.

WOLFSON: I found it on a stock imagery website.

MARTEN: So it’s an existing model?

WOLFSON: It was an existing model. I thought it was amazing that someone had made that.

MARTEN: When I first saw that image, I thought it was a weird HIV metaphor.

WOLFSON: I’m not sure what the original image was supposed to be. I saw it as a romantic image about protected sex. But the HIV virus is also a character in the new video. It floats joyfully around, spinning and expanding and contracting.

MARTEN: I didn’t realize those were hearts inside the condom. I thought they were red blood cells.

WOLFSON: I think they’re supposed to be red blood cells as hearts. That’s what I thought was so interesting. I like that it was made for anonymous use—it could be used in a safe sex advert or on a valentine card.

MARTEN: For a part of the new video, you’re dressed as a dirty punk wandering around the parks of Paris. Who let you get your butt out in front of that fountain? Is this stylized anarchy?

WOLFSON: From the start, it was an important scene. It was the distortion of sex and turning my body into a kind of object or sculpture and also a cliché of a certain type. And yes, stylized anarch—that is def part of it.

MARTEN: You shaved your head for that scene?

WOLFSON: Yes, I had my head totally shaved and I convinced this punk store in New York to let me rent their clothes—this ridiculous leather jacket, this studded undercoat which attached to the belt braces on my jeans, tight punk jeans, a big pair of Doc Martens with spikes, and a T-shirt my friend Audrey lent me that she said had been buried underground for about three years.

MARTEN: Is the punk a conflated image of exuberance and deflation? Or just cool and kind of sexy?

WOLFSON: The punk is the conformist. He is the paradox of conformity and conformity in himself. That’s how it started. But when I was shooting the video, I felt so proud to be this punk and everyone else looked so normal to me in their regular clothing. I felt like I got the whole punk thing wrong, but I didn’t—I was just seeing it from the other side.

MARTEN: When you’re working with your animator, do you sit with them and direct every little movement?

WOLFSON: No. I send detailed scripts to the animators and let them do it as I see fit because they have a whole other set of aesthetics than I do. So I try to let them do it the way they want to do it, and they always bring back something that, at first, I don’t like, and then later I realize a few hours or days later, “Wow, that’s amazing. I was wrong again.”

MARTEN: You do all the cutting yourself, right?

WOLFSON: Yeah, I edit and I do the majority of the After Effects work. I do all the compositing and all of the background imagery. So it’s components I’m dealing with the animator for. But the final work really happens in the compositing and edit.

MARTEN: When you dare yourself to try something, has it ever catastrophically flopped? Do you have a catalog of leftovers that could be resurrected?

WOLFSON: Yeah, of course. It’s not so much daring, but I’ll be like, “Should I do it?” and then I’ll do it, and then, formally, it just might not work out. I would say 90 percent of stuff I try doesn’t work out, but I feel like I have to try as much as I can to get the work to the state where it needs to be—and it’s often accidental. So it’s like setting yourself up for accidents all the time.

MARTEN: Do you talk a lot with other artists?

WOLFSON: A couple. Not as many as I’d like to.

MARTEN: Are there any artists you always return?

WOLFSON: I always go back to Charles Ray and Jeff Koons—early Jeff Koons.

MARTEN: If you were in drag, would it be minimal or maximal?

WOLFSON: Probably both.

MARTEN: You sent me a big, green Japanese knife. It was in a huge blue box with an orange velvet ribbon and nothing else. What does metaphor mean for you?

WOLFSON: I’m not sure. I feel like metaphors are best when they spin in place. Like when they work and don’t work, or lead to a bigger question. That gift wasn’t a metaphor, but more a cipher. That’s how I see you: Helen is a big green knife.

MARTEN: What’s one thing that you totally hate? I don’t mean artwork, but in general.

WOLFSON: I don’t hate things, but I’m turned off by arrogance. I also don’t like power for the sake of power.

MARTEN: Are you frustrated by misinterpretation?

WOLFSON: Not at all. I expect it.

MARTEN: One more question: If people say, “Oh, Jordan’s a romantic,” or “Jordan’s obsessed with sex,” or “Jordan has an ego,” do you care?

WOLFSON: I’m full of faults. I have all of those things inside me. I’m obsessed with all of those things. But it’s like, what am I going to do? People can say what they want. I’m going to keep doing what I’m doing.

Helen Marten is a London-based sculptor and video artist.