John Edmonds’s Sensual, Statuesque Portraiture

Shirt by Coach 1941. Turtleneck, Pants, and Shoes by Lemaire. Vintage Belt from What Goes Around Comes Around.

A recent trip to New York’s Museum of Modern Art is partly to thank for John Edmonds’s new series of photographs. Well, not the actual museum, although the “Constantin Brancusi Sculpture” show did prompt a personal meditation on the nature of authenticity and appropriation. It was a chance encounter with a street vendor named Ali, who sets up shop every day, just outside, with his selection of African arts. Edmonds bought a slender, wooden Baule tribe mask, his first of many, which ultimately led him to create a new suite of portraits of black sitters with his acquisitions.

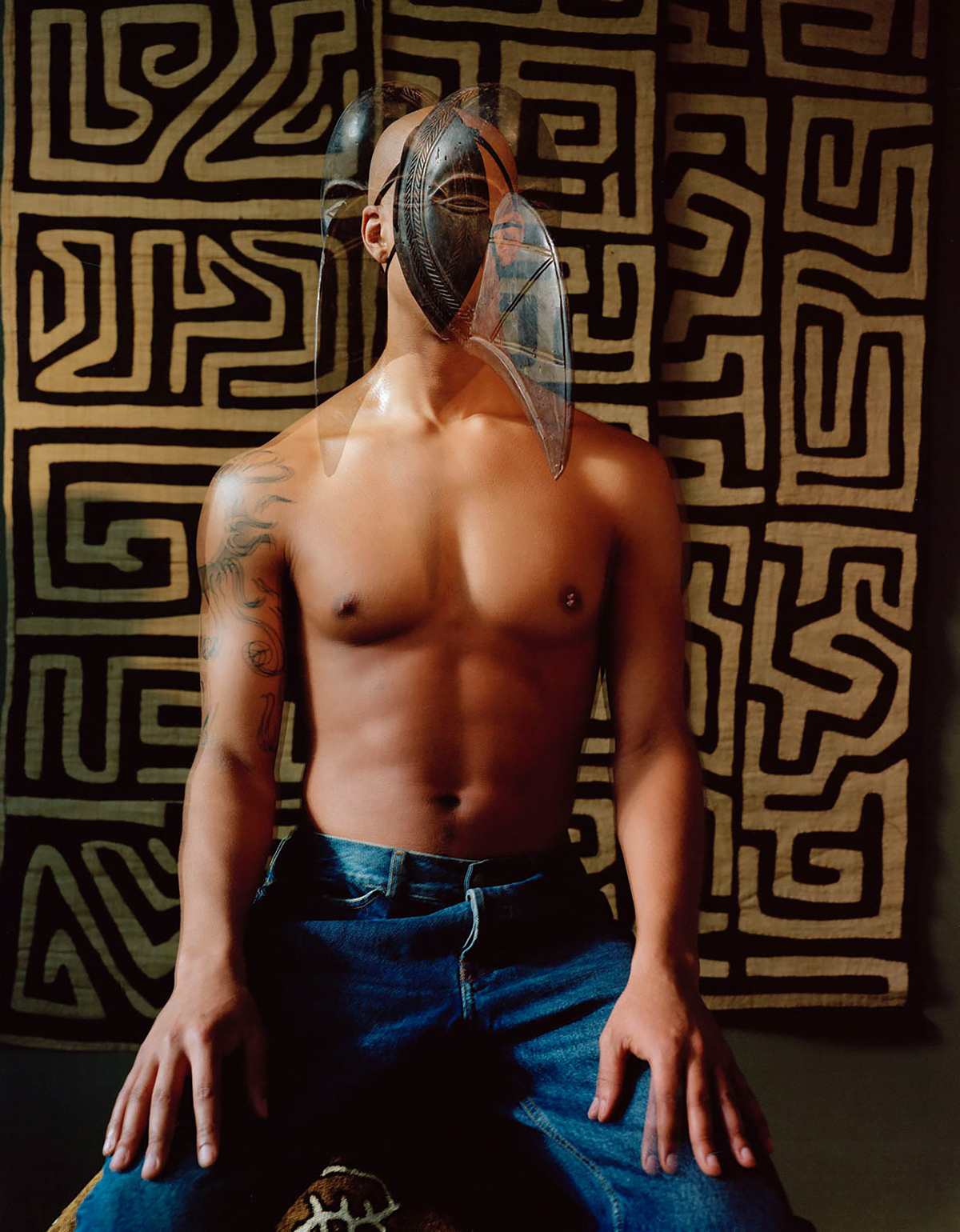

Shot in the intimacy of the 29-year-old New Yorker’s Brooklyn studio and home, the subjects are friends and acquaintances that Edmonds describes as “stunning,” “compelling,” and “statuesque.” In his photographs—some of which are currently on view at the Whitney Biennial, some of which arrive this June at Edmonds’s solo show at Company Gallery—they sidle mesmeric cultural objects: Kuba clothes, Chokwe masks, and various decorative talismans. To invite a sense of candidness into the scene, Edmonds directed a few of his subjects to hold their props until their arms failed them, letting them drop to the floor.

Unlike his 2016 series Hoods, which was governed by a certain shyness—anonymous people in sweatshirts and durags, turned away from the camera in classical, identity-obscuring postures—there is a shift in this new work toward self-awareness.“ With these new works, I had to digest a lot of information and educate myself,” Edmonds says. “My eyes readjusted to reinterpret these objects and consider them outside the context of the museum.”

———

“The people in the photographs are friends who are not in any way professional models. In these two pictures, the men are holding up these clothes, almost offering them to higher spirits. I would have the subjects hold these clothes over a period of time, until they collapsed, which as an act, I think, is a metaphor for life and work. It’s supposed to symbolize the black man holding up history, trying to endure it.”

———

“This subject has a mask on, and there are also two faces, so there’s an element of tri-factor going on: the spiritual, the art historical, and the historical. There is a difference between history and art history. Many masks and objects have been taken out of their original context and history, and as an African American, I’m interested in handling that.”

———

“For me, photographing from behind comes from a desire to represent a more universal being. I’ve often photographed this way, especially in my earlier works with durags. It has to do with experiencing intimacy on a certain scale, like in a movie theater or on a packed train. There’s a shyness in it, despite the fact that I’m someone who walks up to people and asks if I can photograph them.”

———

Hair: Nero