Jenny Holzer

I used language because I wanted to offer content that people—not necessarily art people—could understand.Jenny Holzer

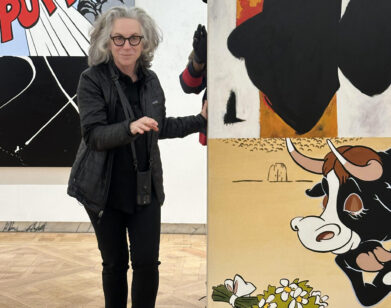

As a private citizen, Jenny Holzer is a woman of few words. As a very public artist–and it is hard to imagine another contemporary American artist whose visual productions have been so publicly accessible–she is a woman of a million words. Words, in fact, are the marrow of the 61-year-old Ohio-born artist’s large-scale, technology-driven productions. Thirty-six years after Holzer moved to New York City, and abruptly turned away from traditional painting to focus on the far more intricate substance of language, her loaded use of mottoes, phrases, verses, and quotations have appeared on T-shirts and posters, marble benches, and condom wrappers, have been light-projected onto the facades of government, corporate, and community buildings around the globe, and perhaps most memorably, have crawled and blinked across red-light LED screens.

While Holzer has relied extensively on poetry and pronouncements from others, using heartening material on war and refugees as well as potent political jargon, perhaps some of her most career-defining aphoristic messages have been her own. In 1977 she began an ongoing series of Truisms (Deviants are sacrificed to increase group solidarity; Money creates taste; Don’t run people’s lives for them; Romantic love was invented to manipulate women) that cogently pared down European and American enlightened thought, co-opted the tone and concision of authority, and disseminated through an endless supply of cultural channels–from baseball hats to billboards.

Holzer simultaneously honors the value of language to communicate and critiques its ability to control and contain. But it is something of a poetic about-face that an artist synonymous with the transparency of the word has spent the last few years not only returning to painting on canvas, but choosing redacted U.S. government documents as her subject. Her latest semi-abstract color-block paintings, reminiscent of those by modernists like Agnes Martin and Ad Reinhardt and Russian Suprematist Kazimir Malevich, both conceal and broadcast various declassified military reports—papers that relate to everything from medical guidelines for detainees to the legality of interrogation methods—in a sense showing by painterly example how certain words are cut from the page so the audience doesn’t suffer the brutal truth in favor of the prettier surface.

These days, Holzer spends most of her time traveling from project to exhibition and working on her paintings in her Brooklyn studio and at home in rural Hoosick Falls, New York. She managed to find some time in her busy schedule to speak with another artist who has long fused politics and aesthetics, Kiki Smith.

KIKI SMITH: I know you went to the Whitney [Independent Study] Program. [Holzer attended in 1976-77.] Was that a big influence on using language in your work—and making work that was accessible to people?

JENNY HOLZER: It was, and the ISP was a refuge from graduate school, where I was on thin ice for being a bad painter. [laughs] Being in the program made me feel less horrible for trying to be an artist. The ISP, and specifically [ISP director] Ron Clark’s love of subject matter, left me more confident about concentrating on work that had content—accessible work. There was a lot of talking and reading in the ISP, so language was welcome.

SMITH: What I always distinguish out of the Colab group [Collaborative Projects, a New York-based art collective that was initiated in 1977 and was active for nearly a decade], and, in particular, people who went through the Whitney program, was something very socially accessible in their work, like Tom Otterness or John Ahearn. Did you start out with language in your work, or were you trying other things?

HOLZER: Painting was falling away by the time I went to the Whitney. I’d been doing projects outdoors for the public. I made pigeons eat geometry by putting bread out in rhomboids and triangles. I don’t know if this activity made sense, but the work was available. And I ripped my paintings and left long colored ropes at the beach for people to puzzle over. I was working outdoors, but I didn’t have any language, any clear content outside yet. Words arrived when I started to write on my paintings inside my studio. All that was in Providence, Rhode Island, before I moved to New York, where writing came to the fore. I used language because I wanted to offer content that people—not necessarily art people—could understand.

SMITH: I remember when I first saw your work outside. For me it was really strange because, as an artist, I never thought about making things outside. Other artists were working with language, but it felt really radical to put it outside at the time.

HOLZER: I wasn’t sure I was an artist, so I thought maybe I just was throwing ideas out for people to consider. That took some of the pressure off. [laughs] The first street pieces were black-and-white posters with the Truisms, one-liners on many subjects written from multiple points of view. I went around late at night to paste these posters downtown. I put the next series of posters outside, too, the Inflammatory Essays.

SMITH: And you were part of Colab.

HOLZER: Colab was a good home, a fine laboratory. My main event with Colab was the “Manifesto Show” that Coleen [Fitzgibbon] and I cooked up together. [The “Manifesto Show” was an open invitation installation held in Fitzgibbon’s storefront space at 5 Bleecker Street in 1979.] I really enjoyed having a partner. I suspect you’ve noticed that making art can be lonely. It was a thrill to have somebody in a project with me.

SMITH: Your work has a deep sense of privacy to it. But yet you’ve often collaborated with others and you have assistants. There is a comfort in having people to work with. And now you’re even using other people’s language in your works.

HOLZER: It can be kind of gruesome at times, making things alone. [laughs] I don’t want to be too dramatic, but it’s hard. It’s necessary to start most work alone. But I’m tickled to death when I can pull somebody in or join someone, whether it’s borrowing poetry or traveling with an associate. Company makes my day.

SMITH: So what was The Offices like in relationship to that desire for community? [The Offices of Fend, Fitzgibbon, Holzer, Nadin, Prince & Winters operated as an art-consulting firm from 1979-80.]

HOLZER: The Offices was another attempt at an artists’ group-a smaller one. I thought it might be easier to work in a little pack. In the end I think it was too late, because we were older and were wanting to wander off solo. The Offices was a perfectly nice concept and kind of a pale reality.

SMITH: In terms of communal activities and aloneness, why did you decide to leave New York [in 1985]?

HOLZER: Mike [Glier, Holzer’s husband] was anxious to get out, and I always like going somewhere else. [laughs] Usually going places makes me feel optimistic. And I’m a hillbilly, so heading to the countryside made sense a number of ways.

SMITH: What about your relationship to horses?

HOLZER: That must’ve had something to do with it. Soon after we moved we got a filly from a blind man. He had to hold a rope to find the barn to feed her, so we all were happy for that change of ownership. Strangely, we named her Lily, almost the name of my eventual daughter, Lili.

SMITH: Was it a long time after you moved there that Lili was born?

HOLZER: Quite a bit later. She wasn’t born until ’88.

SMITH: Do you like your life as protected and calmer outside of New York?

HOLZER: I wish I had a broad perspective on the move. I haven’t achieved that yet. For certain it was, and is, good to be able to be in the dirt and to scratch bugs. I love the animals that have multiplied. I like taking care of what’s at the farm.

SMITH: I always think you made a very good decision. I wish I had . . .

HOLZER: You would have wanted to leave the city so early on?

SMITH: Yeah. Or no. I don’t know. Because another thing about being an artist in isolation is that one can be a little naughty. But now it is so much different. Artists can find people to work with them anywhere, and the Internet has made it easier to communicate. Did anything change in the way you produced your work when you moved?

HOLZER: One thing that changed when I moved upstate was that I became interested in different materials. I started making the stone benches because I was seeing rocks. I make most of my stuff at some remove. I think of a piece, and then people who are competent fabricate it. But lately I’ve started finger painting, which probably should be a joke but isn’t!

SMITH: Finger painting with words or no words?

HOLZER: With a few tough words. My helpers trace declassified government documents on paper and then I add the mark of the hand. I chose documents that were almost wholly redacted, but there can be a little text, such as waterboard or enhanced technique or sedatives.

SMITH: Nancy Spero and Leon Golub probably made the most images of the Vietnam War, at least of artists in the United States. And I think you might be practically the only artist who, in an extremely overt way, is using information and text from the war in Iraq and Afghanistan. What was the history of those war texts?

HOLZER: I’ve been stuck on those documents since 2004 or 2005—almost maniacally stuck, if those words make sense together. I read thousands of pages from files, looking for material that wasn’t in the newspapers. This was a time when the country was still in shock about 9/11 and often supportive of the invasions. Many reporters and publishers were cautious about what was covered and how it was covered. So I went to the National Security Archive and others to get what was written in the moment by soldiers, officers, the FBI, detainees, politicians, lawmakers, policy makers, the Administration, the President, and attorneys for the government. I wanted to know what had gone on. More recently I’ve been concentrating on documents that are almost completely redacted and on trying to paint those in some sort of a wound-down meditative process. At times I throw in color, as a form of hope. Malevich and, oddly, Joan Mitchell and Agnes Martin, plus Nancy and Leon are in mind while I’m working on this series. I used to talk to Nancy and Leon whenever I could. I thought they were individually and jointly miraculous.

SMITH: Are you surprised that so few people have addressed these current wars in artwork? Especially compared to the ’60s when there was an enormous movement of artists addressing the Vietnam War.

HOLZER: It does seem odd. I was a teenager in the ’60s and tried to be in those counter-cultural movements, including the antiwar one that became mainstream. I don’t know why people don’t attend more now, other than that the wars were and are enormously sad and frightful. But it was sad and frightful then, too. What do you think?

SMITH: Things change socially. Certainly artists were tremendously active. And I think some artists were active during these last wars, but not in a visible way. Before, they were part of the forefront. It’s presumptuous to say artists were guides, but they addressed cultural concerns in an overt, visual way. I don’t see so many young people addressing social circumstance, or ecological circumstance, or economic circumstance through art today.

HOLZER: In the ’60s and ’70s, it was often the artists and the musicians who provided alternatives. Now, it has mostly been the comedians fighting the wars, you know? Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert and Bill Maher. Isn’t that weird?

SMITH: That’s true. It’s strange. And also the Internet—it’s where young people go instead of visually presenting themselves in the streets. You had a run of three big shows in 1989 and ’90: Dia, the Guggenheim, Venice [Biennale]. The Guggenheim show was one of the most memorable shows in that museum, formally and contentwise. But I remember for the show at Dia, you were writing the text in your own work. It really mixed the personal and the political and social together in an interesting sense of complexity and vulnerability. Shortly after that you began using other people’s texts, and I thought, When are you going back to using your own texts? That Dia exhibition was so profound to me. It had enormous emotional resonance.

HOLZER: I really wasn’t-and I’m not-a writer. The only way I could write was by pretending to be any number of people. That gave me enough shelter to show what inevitably was personal, but also to have the content be for and about others—since I was busy being somebody else. That worked for a while, but eventually writing wore me down because it didn’t come naturally and my subjects were awful. The visual is easier for me. At some point I thought, I’m going to give myself a break, use my eyes, and go to people who really are writers-mostly poets, because this will let me expand my subject matter and emotional range, and hopefully make the work stronger.

SMITH: Who were the first poets you worked with?

HOLZER: I was hesitant to approach people. I’m socially awkward. But I was working on a number of memorials, and finally it dawned on me: These are memorials to people who wrote, so I should use their writing. That’s how I started to quit. Then a fortuitous encounter in Berlin with the American poet Henri Cole gave me the courage to go to poets.

SMITH: Who were these early memorials for?

HOLZER: One memorial was for the German exile writer Oskar Maria Graf. He had to flee the National Socialists. He set up shop in New York. He went from cafés in Munich to cafés in New York, and tried to live as well as he could. I put his own text back in Munich, in the café of the literature house there.

SMITH: That’s where I am, in Munich, right now. And I know that piece. It was the first piece of yours that I saw in another country.

HOLZER: We put his words on pie plates and the bottoms of coffee cups, because he was a man who liked to eat and drink and write and talk.

SMITH: Do you like working internationally, as in outside the United States?

HOLZER: I went to Europe early. It was the first place I was “officially” an artist, because in New York I was working in the streets all the time, and had questionable standing, if any. But courtesy of Dan Graham, who saw my street posters and showed them to Kasper König, I was in real art shows in Europe in the early ’80s. That wasn’t happening in New York.

SMITH: That was the case with many artists of our generation, and many more before us. They would have long-standing careers in Europe and very little in the U.S. Did it change your perspective, working internationally?

HOLZER: Because I started making memorials and public projects in Europe relatively early, that confirmed the impulse to develop certain kinds of subject matter. For example, artists were invited to make pieces for the [then new Deutscher] Bundestag, so I had the idea of going to archives of German parliaments and presenting what was said by representatives of various parties so that the spoken history could play constantly on an electronic display in the politicians’ entrance. That was a great opportunity for me to get my thinking straight and to find material appropriate for the location and the history. That challenge was a gift from Europe.

SMITH: What’s the difference between making work, like commissioned work, and making work from the studio by your own impetus? How fluid is that back and forth, or how does it change your work?

HOLZER: Sometimes I’m almost exclusively working on projects that someone else has initiated. But since the wars started in the Middle East, I’ve had a double life making the redacted document paintings. I’m not sure these are of interest to many people, but I can’t stop messing with them.

SMITH: You also recently projected those documents on buildings at NYU and other places, didn’t you?

HOLZER: Yes. The documents have been presented in a number of forms, including projections. We projected pages on the library at NYU and the library at George Washington University, which is home to the National Security Archive. So the material that was inside—

SMITH: Was outside.

HOLZER: Many students, both in New York and D.C., thought the material was fake, editorial, and that was wild.

SMITH: I always think of you, Tom Otterness, and I as all solo travelers living out of various airports, always going somewhere. I think that sense of always traveling has something to do with anonymity and privacy and pleasure in having a very clear, very reductive life. What do you think about airports?

HOLZER: I eat lots of peanuts, that’s for sure! [laughs] A certain amount of airport life is necessary because if we are doing a site-specific piece, we have to go there, often before, during, and after the project. And I think another reason is just what you touched on. It’s important to keep life simple, and if I’m traveling, I only can do a couple of things, and those are the things that I’m meant to be doing.

SMITH: You are very involved with commissioned projects—much more so than I am. How do you deal with working with budgets and negotiations and working with the governments and then engineers and architects?

HOLZER: It’s clear that art school should include classes on how to contend with everything from contracts to the commission process. These often can be too much of a voyage of discovery. But I like the stretch because it’s an antidote to freaking out alone in a garret. It’s a different mind-set to negotiate and build timelines and budgets and to form teams. I couldn’t impersonate an MBA and/or an attorney all the time, but it’s good to structure and to bring complex projects home from time to time.

SMITH: Are there any projects that were particularly memorable in the way they stretched your working process?

HOLZER: Working in great buildings is always utterly terrifying, but also gratifying when I don’t blow it. It was heady to be inside the Guggenheim in the ’80s. That was almost too much for me, but I think the installation looked logical and simple when done. Doing a projection on the outside of the Guggenheim was dandy, too. [Holzer used the facade in 2008 in For the Guggenheim.]

SMITH: Were you one of the first people to use the whole space like that?

HOLZER: Maybe so. Anytime I get into a fabulous building like the [Mies] van der Rohe Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, or [Norman] Foster’s remake of the Reichstag or [Frank] Gehry’s museum in Bilbao—that last one was a stretch because Gehry’s work is so curvy and I’m so rigid—it’s good for me.

SMITH: What about Helmut Lang and your collaborations with him?

HOLZER: That was the closest I’ve come to being able to affect architecture physically, and not only react and meld, because the smart and friendly Richard Gluckman [the architect and designer of Helmut Lang’s stores] doesn’t hate artists. [laughs] He let us mess around and do things like integrate LEDs into railings.

SMITH: How did the relationship with Helmut Lang come about?

HOLZER: Ingrid Sischy put us together for that art and fashion biennale in Florence [Biennale di Firenze, 1996]. I think Helmut’s first pick of a partner was dead. Our pairing was thanks to Ingrid, and she chose wisely. I liked Helmut immediately and enormously.

SMITH: I can see that your styles work together very well.

HOLZER: A little mean, and less-is-more.

SMITH: What about living with another artist? Are you and Mike close as artists?

HOLZER: What could be better than having another artist handy to bounce art questions off? When it’s working, it’s divine to have another artist to call over and ask, “Does this stink? Does this have legs? Does it stink but have legs?” Another good part is that our kid has a visual vocabulary. It’s second nature for our daughter to look and analyze. On the worst days, we’re both sensitive, neurotic, hard-to-be-around, and needy, but annoyed by the other’s presence and work. [laughs]

SMITH: But that isn’t art-specific.

HOLZER: No, it could be worse.

SMITH: There aren’t that many couples who are artists. Of course there have been some—Nancy and Leon, Betty and George Woodman. But there aren’t many, at least who have stayed together for many years. And, at the same time, I think you give each other a lot of space. You’re both very engaged in your own work and then manage somehow to occupy the same spaces periodically. I think that’s unusual.

HOLZER: We’re gone a lot. Right now he’s painting in New Zealand and I’m in New York, but we talk about the kid, and I talk about my new painting crisis, which makes him laugh because he’s more experienced with painting crises than I am. And I think it’s a giggle for him that I’m making finger paintings.

SMITH: I’m sure that’s true. I’m curious also about your relationship with other artists. What about your relationship to Louise Bourgeois?

HOLZER: Before I talk about Louise, I will say that you, Kiki, are all over my house. I mostly have art by women. It seems these were the natural choices. I didn’t set out to make a domestic museum of women’s art, but I did. Early on I acquired a number of Bourgeois’s drawings because I thought her astonishing mind was especially evident in her drawings—not to mention her sculptor’s hands. And she’d draw just about anything, with very little off-limits. I never spoke to Louise much, because I’m bashful—although the times in her house are vivid-but I thought about her work and her with great and reassuring regularity.

SMITH: Do you have fantasies for what will happen to your work when you’re dead? Do you think about where your work should go or your archives should go?

HOLZER: [laughs] I have more fantasies about being dead than about my work right now.

SMITH: So it’s not something you think about very much?

HOLZER: I would like somebody or an institution to accept the gift of a bunch of those secret-document paintings so they could stay together. Maybe a dusty basement corner of the Smithsonian could house the paintings. I’d like them to be together so the voices of the officers and the soldiers and the people planning the war and the detainees, as well as the president-all of those statements would be there. That’s my Americana. I’d like there to be good, soft chairs so you could stay for a long time and sometimes look and sometimes read. [laughs] That’s the other part of the fantasy: the texts together, the paintings grouped, and good, merciful upholstery.

SMITH: What are the next forms or structures that you are you interested to engage with? Are there any unmapped spaces that resonate?

HOLZER: I’ve been slow to do this. I’ve been meaning to try harder for at least a decade, but I want to make more pieces for handheld devices, because I think my stuff could live happily there, in tablets and phones. I’d like to provide eye candy and content for them.

SMITH: Is that far off from making those paper cups you did so long ago?

HOLZER: I made Styrofoam cups for Ron Feldman’s “1984” show [Ronald Feldman Gallery in SoHo], with Orwellian sentences printed on them, such as the future is stupid. I should be so lucky as to invoke Orwell on little electronic devices now.

SMITH: I have some of those cups put away somewhere. I also have some of your Xeroxes that went outdoors.

HOLZER: Thank you. I’ve also been messing around with teeny personal projectors, so if you want, you can project writing outside or cover a whole wall in your house.

SMITH: You were really one of the first artists to overtly embrace new technology—when LED was a new technology. You make things by hand but you’re also kind of a techy person.

HOLZER: Yeah, I’m not sure where that comes from because I have no real competence, but I was in love with a couple of physics guys once, so who knows?

SMITH: That works. Love is a big motivator.

HOLZER: I think that’s part of it somehow.

SMITH: What do you think is the difference between making art and making T-shirts? Is it just a formal difference or what?

HOLZER: I like placing content wherever people look, and that can be at the bottom of a cup or on a shirt or hat or on the surface of a river or all over a building.

SMITH: There are also different levels of intimacy. If you live with a painting or you’re in a building with a painting or a painting is being projected on the side of the building, or if you can walk around with something in your pocket . . . Those are just different levels of intimacy.

HOLZER: I have shirts you’ve made. I have a scarf of yours carefully folded on the shelf in my closet and I look at it from time to time. It’s good to make what people can have and hold and wear.

SMITH: And now for the near future you’re doing your paintings.

HOLZER: I’ve filled an abandoned recital hall in upstate New York because I keep making these paintings. It feels necessary. There’s no official purpose, but once in a while, a few of the paintings go someplace.

SMITH: But it’s nice to have multiple lives, to have episodic lives, but also artistically to have different kinds of outlets for your work.

HOLZER: It’s good to be employable, but I hope to show the truth. The paintings seem true because nobody wants me to do them. [laughs]

SMITH: You’re working with paper. In the beginning, your work, like Truisms and the Inflammatory Essays, used paper as well.

HOLZER: Yes, I used paper and my wheat-pasting arm.

SMITH: So it makes sense that it’s something that is part of your work. And you’ve used color very dramatically in the LED work.

HOLZER: Color has always been around. Until recently, I felt I had to sneak color, but now I just paint it.