LIT

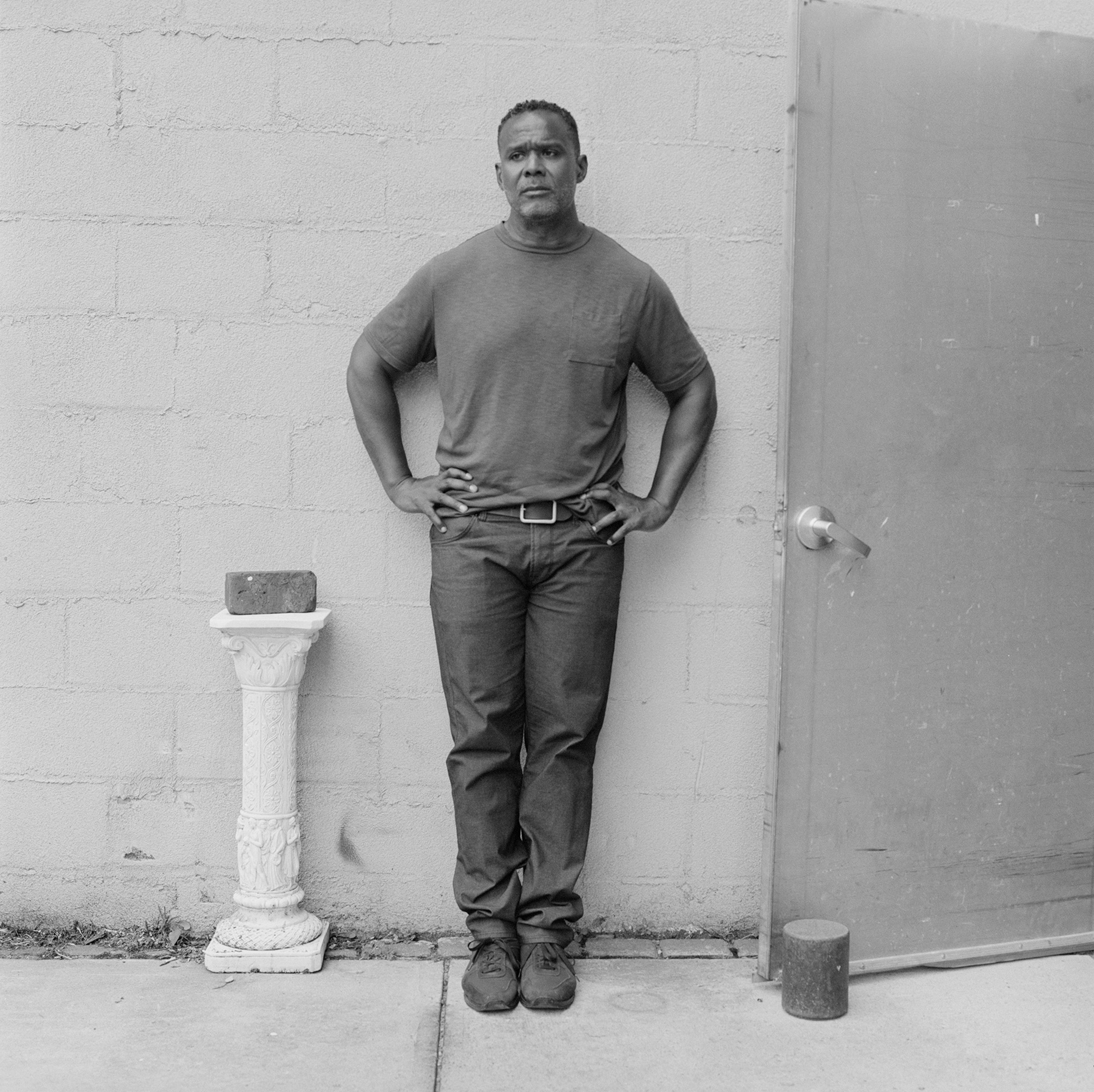

James Hannaham Connects the Dots Between the Tragic and the Absurd

For the cover of James Hannaham’s latest novel, Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta, the writer invited artist Kalup Linzy to create a collage that represents the character of Carlotta Mercedes (a tough, wise, misunderstood trans woman, portrayed in various photos by Linzy) who has been paroled from a long stint in a men’s prison and returns to her greatly changed Brooklyn neighborhood to try to sew her life together again. Hannaham and Linzy met a decade ago in the New York art world, and forged a friendship during their overlapping stays at MacDowell artists’ colony in New Hampshire in 2017. As a creative dynamo, Hannaham is the real deal, cocreating the pioneering performance group Elevator Repair Service in the early 1990s, and working in art, music, theater, and journalism before writing two acclaimed novels. Carlotta, though, might be his most tender and tenacious, with the ear, soul, mouth, and swagger of a real New Yorker. Hannaham and Linzy spoke over Zoom about tragedy and humor, ex-gays and ex-ex-gays, and being different and staying that way.

———

JAMES HANNAHAM: How’s it going?

KALUP LINZY: Pretty good. I’m in Tulsa, where I have this artist residency. What are you up to?

HANNAHAM: I’m away for the weekend, in Rhode Island with my husband. His parents have a house up here.

LINZY: I was going to say, that doesn’t look like New York behind you. Okay, I guess to start off, I want to ask you about some of the defining moments of your childhood.

HANNAHAM: There was so much stuff that happened that pushed me in one direction or another, often a feeling of failure in certain endeavors. I grew up in Yonkers, which is famous for being mentioned in a lot of jazz songs.

LINZY: Isn’t Mary J. Blige from Yonkers?

HANNAHAM: Yes. She went to my high school. I can tell you a defining moment about Yonkers. In 1980, the federal government sued the city of Yonkers for segregation of the school system. The city lost the case. But even before that, my education was already defined by the fact that they were always trying to redraw the school district lines. I was in a Black neighborhood in the middle of the city, and the only other neighborhood with a significant population of people of color was Mary J. Blige’s neighborhood, which was on the lower west side, about a square mile, that included some low-income housing and projects. She grew up in one that’s called Schlobohm, which they referred to as slow bomb.

LINZY: Wow.

HANNAHAM: By the time I graduated high school, the whole thing had gotten to the point where the city council was defying a federal court order to institute lower income housing on the east side. They were defying the order, right? But when they lost the case, they had to integrate the schools. There were a lot of angry people being like, “No, don’t do it in our neighborhood.” David Simon made a whole miniseries about it called Show Me a Hero, and while it is fascinating, it also cuts out the people of color who actually started the lawsuit. I know this because my mother was a reporter and this was a story she was working on.

LINZY: You and Kara Walker are first cousins, right? I always imagine her growing up in the South.

HANNAHAM: She grew up in California. Her dad is the painter Larry Walker. My mom and her dad were the last two of 11 children from Georgia, who moved up to Harlem during the Great Migration. He got a job out in California at a certain point. Eventually they moved back to Atlanta, so she had a gigantic culture shock coming from California. I think in a lot of ways her work comes out of that culture shock.

LINZY: My family also went north and then farther south after Emancipation so I have cousins all over. When I first moved to the city, I was going to stay with them, but I felt so different from them and wanted to find my own way here. So here I was from the rural South landing in the big city. But it is interesting how a lot of the Black community moved back and forth between the South and the northern parts of the country.

HANNAHAM: We call that Up South. The first two books I got published are set in the South.

LINZY: Before you published those books, you co-founded this performance group in the early ’90s called Elevator Repair Service. How did you first come in contact with performance art?

HANNAHAM: I spent a lot of time in the library when I was a kid. One of them was this beautiful modernist gem in the middle of Yonkers. It was very close to my high school, and there was an alternative record store next to that. So it was a one-stop alternative culture shop. And the Village Voice was always available in the upstairs mezzanine, which was the arts and media area. I would sit there a lot and read the Voice. At the time, performance art was what was happening in New York. I was so enthralled, especially by Cindy Carr’s pieces about Karen Finley. It was also the time of this amazing PBS show called Alive from Off Center.

LINZY: When I was in high school I had no idea I was a performance artist. I knew I liked theater but I didn’t get into performance art until college. But you got to see it on television as a kid. Speaking of, weren’t you on the pilot episode of Queer Eye for the Straight Guy?

HANNAHAM: Yes, as the “culture guy,” but I was replaced before the show went on air.

LINZY: I know there was a lot of talk about wanting a person of color as a cast member, and I don’t want to misinterpret what happened. But even in queer communities, there’s a certain level of racism and colorism that happens.

HANNAHAM: It’s a pretty high level, actually.

LINZY: Your first novel, God Says No [2009] dealt with those themes.

HANNAHAM: It starts at a Christian college in Florida and bounces around. He winds up in Atlanta, and then he’s in a so-called reparative therapy place much farther out West.

LINZY: I grew up in Florida and it’s such a conservative place. Now I’m in Oklahoma and it’s just as conservative as my upbringing was in the ’80s.

HANNAHAM: One of the reasons I wrote that book was because I kept noticing things that made me think, “Didn’t we do this? Aren’t we over this already?” But these were things that were happening in the northeast. I would hear stories about some guy who was a Wall Street executive, literally living a double life, where he would go out and be gay, and then another one where he was working and being a professional. The character developed out of reading all these testimonials by people who claimed that they’d been cured of their homosexuality, and they were really funny documents to me. A lot of them would hinge on magical visions of Christ. My favorite was about somebody who was at a gay dance club, and all of a sudden everyone’s face melted, and Jesus came off the dance floor.

LINZY: They were probably on drugs.

HANNAHAM: Jesus says to him, “My child, this is not what I want for you.” It all seemed very sketchy. A lot of the dots had not been connected in the narratives. I thought to myself, “I wonder if I could write a narrative where I did try to connect all those dots.” Even on ex-gay websites, you discover that a lot of the ex-gays become ex-ex-gays. The joke among people who have gone through that therapy is, the first night, you choose your prayer partner. The second night, your prayers are answered. It does not cure anything.

LINZY: It’s always funny how people claim to be cured by saying, “I am still attracted and have those desires, but I’m just not acting on it.” It reminds me of growing up in the church. I felt like I wrestled with that for so long, that I just had to say, “Gosh, I’m tired of fighting myself.” I’m curious about your writing process and character development. I wonder if they’re similar to mine. I’m in my characters, but a lot of it is based on imagination and fantasy.

HANNAHAM: This gets back to your question about formative experiences. I was 18 months old when my parents divorced. I have no memory of my father being in the house. But I think I felt responsible for it for a number of reasons. I was a hard birth, and my father ended up going back to his girlfriend that he had before and during their marriage. But because of that divorce and in order to make some space for myself and get some positive feedback, I would do all kinds of stupid characters and make jokes and try to cheer people up, my mother especially. I think that became the beginning of a performance jones.

LINZY: Wow.

HANNAHAM: When it came to writing, it wasn’t that there was ever a switch. When I came to New York, I got a job as a part-time design assistant at the Voice, which paid badly, so I’d try to make extra money writing articles at places like Details. There was a lot of energy at the Voice at the time. Colson Whitehead was the television critic. So there was some social pressure to write a book, and I didn’t want to write nonfiction. The only other option was a novel. In an amazing stroke of luck, the only person I knew who had some success in the literary world at the time was the girlfriend of a theater director that Elevator Repair Service had worked with, this guy named David Herskovits, and the woman who is now his wife, Jennifer Egan.

LINZY: Amazing.

HANNAHAM: I was like, “Would you take a look at this thing that I wrote?” And she marked it up like crazy, but gave me the feeling that maybe I could do it.

LINZY: What was the story you gave her about?

HANNAHAM: I think it was about a Black gay man who killed a Republican senator accidentally during rough sex.

LINZY: That’s hilarious.

HANNAHAM: It’s a narrative I’ve been mining ever since. In some way, everything has flowed out of that concept.

LINZY: When did you start writing [Hannaham’s second novel] Delicious Foods?

HANNAHAM: In 2008. But I was thinking about it long before that. In grad school, I took a course called Cultural Tourism, Slavery Museums, and the Modern Neo-Slavery Novel. We read a whole bunch of books, mostly by Black authors, that dealt with slavery in some way or another. That got me thinking about the neo-slavery novel as a rite of passage for a Black author, which is a funny idea to me, because I think there are these books that are a rite of passage for people of various demographics, like the novel about the 1930s for the white woman. But I started to wonder what that book would be like for me, and I feel like one of the problems of writing about slavery for a modern audience is that it’s too easy for them to be like, “Oh, that happened in the past. You people should get over that.” During the course of researching a book, I came across a book called Nobodies [Modern American Slave Labor and the Dark Side of the New Global Economy] by John Bowe. It was the story of a particular Black woman and her husband who were enslaved in Florida in 1992. I lost my mind. I was like, oh my god, this shit is not over. Saying that slavery is over is like saying that drugs are over because they’re illegal. There’s some drive toward cheap labor that our culture, our economy, really, really wants. And people will stop at nothing. Why should they stop at exploitation and cruelty in order to achieve their aim?

LINZY: These seem to be themes that run through all of your work, right up to Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta.

HANNAHAM: I think the theme, modern existence, is difficult and people try to exploit your ass, especially if you are a person of color or a queer person or a queer person of color. But we have to try to get through it. A traumatic existence is about using humor as a way of just getting through it. I don’t think there’s anything serious that cannot be, on some level, seen in a humorous way, even if it’s not funny.

LINZY: Yeah. Even in my family, when someone passes away and then you have the funeral service—it’s the moment after the funeral that the families are giggling because somebody was being extra.

HANNAHAM: There’s just so many moments of absurdity, followed by tragedy. That gives a story the texture of life.

LINZY: There’s a kind of humor that can be healing. Carlotta is sad, but there are still some very funny moments.

HANNAHAM: Yeah. It’s sad, frustrating, but also, I wanted the novel to feel like walking around on the street in New York.

LINZY: You also had a lot to say about the current state of the prison system. When a person gets out, when they’ve done their time, they’re still judged and looked down on and not trusted. Psychologically, it really continues to tear up communities.

HANNAHAM: Yeah. And the institution itself. One of my themes is just this feeling of society attempting to make a world that’s one-size-fits-all, even if it’s not right for you. There’s only one sort of consumer, and they only have one demographic, and I’m never it. So I’m almost always like, what the fuck?

LINZY: The fact that the character in your book is transgender adds a whole other layer to it.

HANNAHAM: Part of what made me so interested in this character is that she is obviously in the wrong place, but the rules are saying that she has to be in the part of the prison that she’s in. That is the essence of what’s unjust about that situation. As an individual, it can be that obvious that an environment is wrong for you, but if there are these societal controls involved, you can’t say anything. Black people need Kafka. You know what I mean? There was a copy of Kafka’s short stories in my bathroom for years and years, and my brother and sister and I read it a lot. But just that feeling of being an individual, up against a massive bureaucracy that’s sort of faceless and emotionless and indifferent to your peculiarities, indifferent to you as an individual, and your idiosyncratic needs and the ways in which you differ from the norm. That’s kind of fundamental, I think, to everything I’m doing. I just want there to be more space for people who are different in whatever way they happen to be different, partially because I feel that way all the time.

———

Grooming: Remi Moore using R+CO

Photography Assistant: Tyler Woodford