Jaamil Olawale Kosoko Plumbs His Archive

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko wears a variety of hats as poet, artist, curator, and performer; and at the Miami Theater Center in conjunction with Art Basel Miami Beach, his latest project incorporates all of them. His bold works, which feature everything from poetry to performance, are both referential and completely original. The Nigerian-American artist’s world premiere of “BLACK MALE REVISITED: Revenge of the New Negro” attempts to expand notions of black masculinity through a first-person narrative. A foray into the dramatic and vulnerable elements of identity, Kosoko uses body glitter, animal masks, and his own history to mount this multi-faceted work. We caught up with Jaamil in between installing and chatted about shows at the Whitney, curating yourself, and project speed dating.

EFFIE BOWEN: Your show is described as a mini retrospective of your work. What works comprise this project?

JAAMIL OLAWALE KOSOKO: Basically, I’m retracing my steps. Much of my current practice is rooted in the contemporization of history. “How can I make the past more present than the present?” is what I ask myself. For the first portion of the “BLACK MALE REVISITED” project, I’m recycling my 10-year-long archive of solo and group pieces and transcribing them into a new, solo, evening-length work.

BOWEN: Are these performances? How do you transition a group work into a solo work?

KOSOKO: Yes, they are performative, but some were made specifically for video. I perform in all of my pieces, so I extract my part from the group.

BOWEN: How did you pick which works would become a part of “BLACK MALE REVISITED”?

KOSOKO: The selection process was an instinctual one. My original concept for this project was to bring into focus a multi-tiered platform bridging all my interests: curation, performance, visual art, and discussions, while allowing enough room for pop-up performances and ancillary events. I wanted to create a performative platform that would change its contours as it migrated from one city to the next.

BOWEN: Do you adopt a different approach when you curate your own work compared to works of others?

KOSOKO: When I approach my own work, I consider myself more or less a “curator of content,” carefully selecting materials and moments that reverberate inside me and that I hope will resonate with others. When curating the work of other artists, especially when it comes to live performance, there’s more sensitivity. It’s my responsibility that each artist feels supported, listened to, and well taken care of.

BOWEN: The components of “BLACK MALE REVISITED” involve performance, an installation, and audience discussions. How do these different elements all function as one piece for you?

KOSOKO: For me, there has to be some kind of engagement element attached to the project, a contextualization for folks who are new to my work and the concepts that artistically obsess me. Furthermore, it feels deeply important to me to push forward the conversational or educational component of this project, as so much of my process involves researching and conversing with scholars, artists, and pedestrians.

BOWEN: What concepts currently “artistically obsess” you?

KOSOKO: Issues that relate to history, politics, and identity concern me deeply. The constructs of privilege and race also intrigue me, as does the way all these concepts can converge into an aesthetic performative practice. I’m also really excited by the erotic and/or provocative.

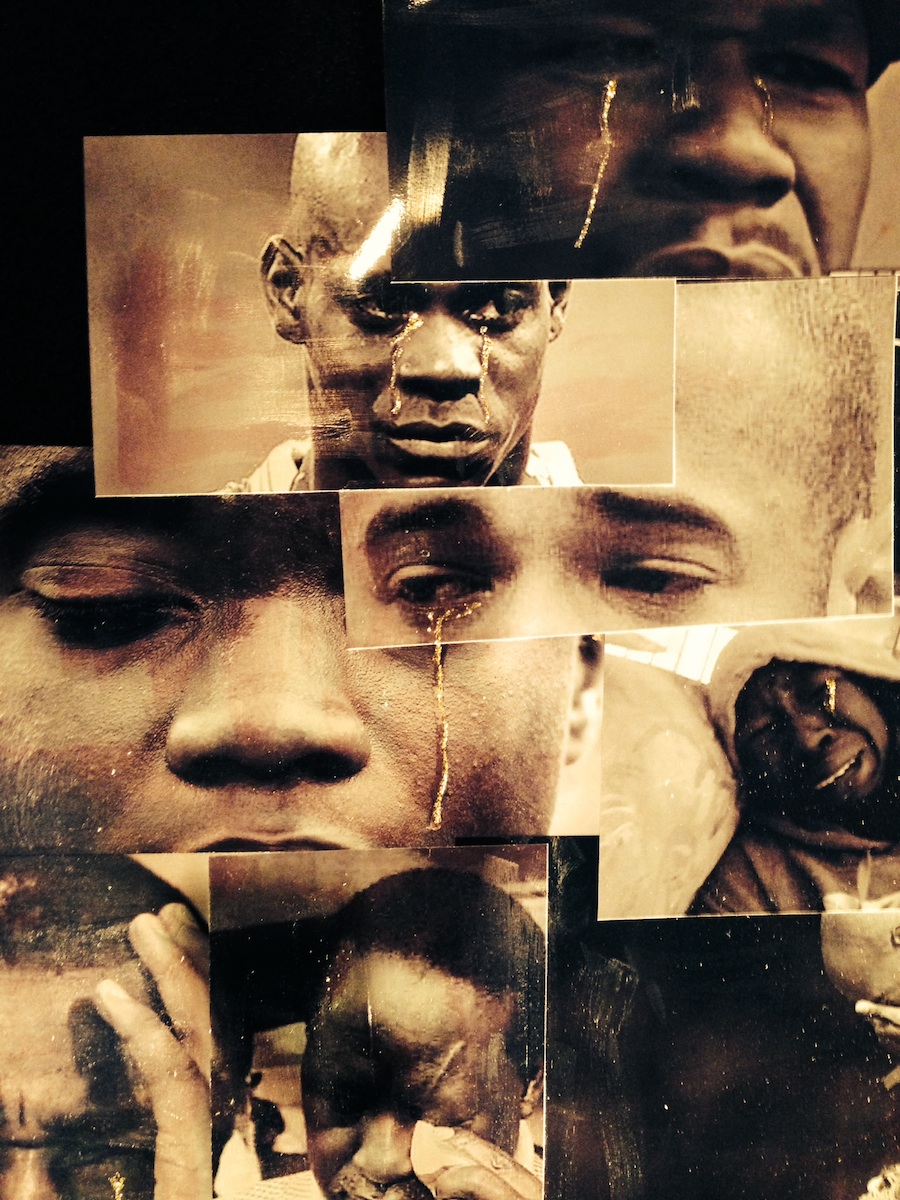

BOWEN: How did you conceptualize the installation component, Cry?

KOSOKO: Vulnerability as a performance strategy has always been a deep concern in my work. As I situate my practice within the visual art frame of Art Basel Miami Beach, that concern is even more present. I believe there is a fierceness and strength that comes with exposing personal worlds and ideas. So often in public, black men experience societal pressure to protect their masculinity by adopting an over-exaggeration of manliness. With Cry, I show the antithesis to that kind of masculinity, one that is also filled with sensitivity and humanity.

BOWEN: How does the performance compliment or contrast Cry?

KOSOKO: That’s a good question. Perhaps it’s important to know that I have a nervous breakdown in the show. I push myself into complete emotional collapse. My mother suffered from mental illness and a crippling nervous condition that I witnessed first hand. I think being in such close proximity to her continual demise had a deep impact on me. In this way, the work becomes quite autobiographical. I consider the entire installation a sentimental black male space. I have gold fringe hanging that represent tears as well as our stereotypical attraction to gold chains and bling.

BOWEN: Are the portrait images found?

KOSOKO: Yes, all of the images are sourced from the Internet. There’s a real rawness to the entire show. This is my first time expressing myself so explicitly, with objects, film, writing, and performance all combined.

BOWEN: Do you ever struggle performing these extreme and personal states multiple times?

KOSOKO: That’s not an issue for me. While it’s physically draining at times, the emotional work is all theater. I guess I’ve been training and working in this way for so long that I’m use to it.

BOWEN: The 1994 exhibition “BLACK MALE” at The Whitney served as inspiration for you; how does it inform “BMR”?

KOSOKO: This whole concept is in a metaphorical conversation with the original “BLACK MALE” exhibition. It’s really important to me to look back and pay homage to the integral ideas that have shaped my thinking and progression as an artistic figure. While I am in conversation with the “BLACK MALE” show, my “Revenge of the New Negro” is very much its own world. I want to push the discussion forward reignite a younger generation of artists, intellects, educators and the like. The landscape for black artistry has changed so much in the 20 years since the original “BLACK MALE” exhibition; It’s just a really exciting time to experience black space.

BOWEN: Did you start out working in one medium and graduate to others or have they been developing simultaneously?

KOSOKO: Wow, the more I think about it, I believe they all have been developing simultaneously. I’ve always loved drawing and painting since I was a kid in art class. I was a poetry and photography major at Interlochen Arts Academy in Northern Michigan. I went to Bennington College where I studied dance and art history, from there I went on to study film and poetry in the U.K. at the University of Kent, Canterbury. I also studied Performance Curation at Wesleyan University, so really “BLACK MALE REVISITED” is a way for me to combine all of my varied interests.

BOWEN: What is next for you, after Art Basel?

KOSOKO: Well, I’m doing some project speed dating at Under The Radar Festival in January to promote this work. I’m also curating “BLACK MALE REVISITED: Experimental Representations through the Ephemeral Form,” the second part of this project, at Danspace Project as a part of their Food for Thought series, February 6 through 8, 2014. I’m showing at Movement Research at Judson Church in the spring and traveling in the summer.

BOWEN: Is project speed-dating as fun as it sounds?

KOSOKO: It’s when you meet artistic directors and curators to pitch your project in 10 minutes or less. I have to get the word out somehow. [laughs]

“BLACK MALE REVISITED” RUNS THROUGH DECEMBER 22, WITH A PANEL DISCUSSION ON DECEMBER 7, AT MIAMI THEATER CENTER, AS WELL AS THROUGH ART MIAMI ON DECEMBER 8. FOR MORE ON JAAMIL OLAWALE KOSOKO, PLEASE VISIT HIS TUMBLR.

For more of Interview’s coverage of Art Basel Miami Beach, please click here.