IN CONVERSATION

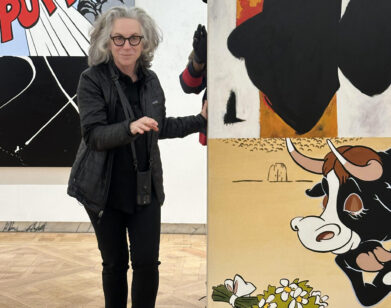

How the Painter Ivy Haldeman Critiques Consumerism With Hot Dogs

Ivy Haldeman, a master of personification, uses hot dogs and suits to bring you to your knees either in pensive thought or despair. “The drama of the painting isn’t in the storyline of the hot dog,” Haldeman explains. “It’s the emotive interaction you’re having with their body language on the picture plane.” In her upcoming show at François Ghebaly gallery in Los Angeles, the New York-based artist uses these fluidly constructed images of feminized sausages and headless suits to critique practices of exploitation, labor, and performativity in a capitalistic and patriarchal society obsessed with productivity. Haldeman’s goal is to make the viewer ask who is watching, and who the hot dog is performing for? The ceramicist Genesis Belanger, a peer and longtime admirer who shares the same grievances with consumerism, follows similar lines of inquiry in her own work, which convey half-eaten watermelons and hands adorned with rings to illustrate the commodification of the female body. Last month, Haldeman and Belanger got on Zoom to chat about personal protests against the beauty industry, little lizards at The Met, and the Upton Sinclair novel that started it all.—ARY RUSSELL

———

GENESIS BELANGER: Hi.

IVY HALDEMAN: Hey, hello.

BELANGER: How is your upcoming show going? Will you be showing the new works you told me about or is that under wraps?

HALDEMAN: I hope to be sharing the new works. It’s funny making something new.

BELANGER: When do you release new things into the wild?

HALDEMAN: It’s a slow process. I’ll take my sketchbook to a friend’s house and be like, “What do you think?” Then show another friend a picture on the phone and be like, “First reaction, how are you feeling?” And it slowly starts to become public.

BELANGER: I always show the new stuff. I figure that putting it out to the public is the best way to get the strongest reaction. But I feel like you work with tighter series than I do. Would you agree?

HALDEMAN: That’s interesting. I guess you have a little more flexibility in terms of the objects that you are making.

BELANGER: So how do you decide what a new series will be?

HALDEMAN: I do ultimately decide, but I feel like there’s never a point where I say, “Oh, I have made a decision.” It’s a process of having lots of different visions and giving them some kind of visual form and then seeing how they live in the world and how they make me feel. I hope to be showing a new series in January, which I started thinking about last September, but it took four months before I even understood what direction it should be going in. Talking about artistic processes is so vague and abstract.

BELANGER: Absolutely. But you have a few series that you return to, and you are able to build entire bodies of work from a very specific arrangement of forms. How do you choose them?

HALDEMAN: When making a painting I’m thinking of it as a type of theater, and the actors are basically composition and readable body language. Those are going to create the points of drama more than a series of changing characters. So sometimes people ask me if the hot dog figure is a character or if this character meets other characters, but the drama of the painting isn’t in the storyline of the hot dog. It’s the emotive interaction you’re having with their body language on the picture plane.

BELANGER: That makes sense. So you’re more interested in revealing this subtle non-verbal language that we all speak fluently but are maybe unaware of.

HALDEMAN: You’ve said that so beautifully. It’s like arguing with somebody and you’re telling them all the things they did wrong, but it often doesn’t matter what the person is saying, it just matters that they’re upset. And the content of the words is almost useless because you’re not going to convince them otherwise. It’s about somehow resolving the emotional conflict, not the rational conflict.

BELANGER: Absolutely.

HALDEMAN: It doesn’t really matter what I’m painting in a certain way. My figures are very important to me and they have a lot of meaning. But the content of each painting is in the body language of the figures.

BELANGER: It’s not a narrative.

HALDEMAN: It’s not. Like being in New York City, you’re walking down the street watching people, and you’re getting snapshots into their lives and you can just tell how incredibly deep and complex each one of their situations are. Trying to capture that in the painting without distracting oneself with too many items or objects is part of the challenge.

BELANGER: Do you feel like from the hot dog to the suit, you’re paring down to see with how few elements you can still evoke that non-verbal expression of the body?

HALDEMAN: Genesis, you’re incredible, because I think exactly that. The hot dogs have faces and hands, which is immediately easy for us to relate to as people. And then the suits have no hands, no face. So how do you still find a point of emotive entry? It was a progression of that content pursuit.

BELANGER: This beautifully leads us to your new work. Do you want to tell me a little bit about that?

HALDEMAN: I don’t know if I should talk about them before they are presented in the real world.

BELANGER: Maybe this can just be a tease then.

HALDEMAN: I feel like as I’ve been painting my hot dogs and suits, I’m thinking about an American experience. With the hot dogs, I always thought about The Jungle by Upton Sinclair. In high school, I just remembered it being about food regulation and the meat industry because it was disgusting. But then you read the book and you realize it’s actually a book about immigrant labor. It’s kind of twofold because it’s the working conditions of the immigrants, Lithuanian immigrants specifically, but also the mythical narratives of America that convinced them to leave a situation that is actually not bad. They actually have a nice life in Lithuania, but the dream of America is so bright and exciting that they give it all up to work themselves to death in Chicago.

BELANGER: Right.

HALDEMAN: I’m always thinking about labor and painting. I was looking at a lot of ukiyo-e prints from the Japanese Ito era, the late 1800s, of women who are courtesans. The images are used to advertise their presence. It’s interesting to decontextualize that as a beautiful drawing and then remember that this is an advertisement for sex work. So these hot dog figures are a product of industry. They’re lounging on the canvas, but they are working ultimately because performing for a viewer, even just presenting yourself visually, is a form of labor. So the jump to the business suits was very literal. When you have a figure on canvas, specifically a woman, in many instances you’re watching them perform for a type of equity. Somehow that all connects to America.

BELANGER: I think so.

HALDEMAN: The hot dogs are about leisure and labor connected. The suits are very much about labor, but also about finding agency in the working body. It might be an elusive shell that you wear. So I’m really excited about my new series. It’s about how we use images to create financial structures that dominate the world. Anyway, they might not read like that. They might just look like vacation paintings.

BELANGER: I doubt it. And I think when things operate on multiple levels, that’s when they’re most successful. So hopefully they’re both a vacation painting and a critique of America and women’s roles in it. And also with the fewest amount of elements communicating that nonverbal action of the body. It’s interesting that you bring up The Jungle because that was an extremely formative novel for me as well.

HALDEMAN: Oh my god.

BELANGER: In fact, I became vegan for 12 years. Vegan for the people, not for the animals. [Laughs]

HALDEMAN: Yeah. That’s so incredible. What made you read it?

BELANGER: I think I was living in Chicago at the time.

HALDEMAN: Oh yeah. You’re like, I should know my city.

BELANGER: Yeah. I love a historical novel as well.

HALDEMAN: God, that’s so good of you. That book was really amazing at capturing the material conditions of these immigrants and describing how when a family unit breaks down, everybody’s health starts to deteriorate. But it wouldn’t have if this family were allowed to take care of each other instead of putting all their labor into the meat industry.

BELANGER: That novel was my first awareness that we continue to internally exploit. Sometimes it’s easy to think that’s the past. And not to realize that it doesn’t go away, it just shifts.

HALDEMAN: Is there a source of literature that was really inspirational for the work that you’re doing?

BELANGER: I listen to books while I work so I’m just voraciously absorbing information, but I don’t know that I can draw any direct lines. I think what directly influences me most these days is advertisements. The object changes, but the formula doesn’t. So even though we’re not advertising sex work, we’re still in some ways using women’s bodies as a way to sell things.

HALDEMAN: Do you think about cosmetic advertising in particular?

BELANGER: That’s where it’s most obvious. But even for telephones and wrenches and every single thing, a part of or a full female body is often used to sell it.

HALDEMAN: Sometimes I think about the cosmetic industry and how a majority of those profits come from women. So when someone’s like, “Oh, I’ve started a cosmetic brand, now I’m a billionaire,” you’re like, is that actually moral money? I don’t know.

BELANGER: I did this personal experiment for a few years where I lived my values and didn’t participate in any feminine grooming. I didn’t color my hair, wear any makeup, do my nails.

HALDEMAN: Which is amazing, because whenever I encounter you in real life, you are incredibly immaculate. Never done up, but immaculate.

BELANGER: Well, I’m not doing that anymore. You realize that there’s a cost, even though there shouldn’t be. The way that one is treated if you don’t participate in the grooming is different and distinct. I don’t find my personal value in being appreciated for being handsome, but it really exemplified how powerful that pressure is. It’s a machine you can’t remove yourself from. Or if you do, you need to be really, really strong.

HALDEMAN: You have to have some incredible form of power or wealth in order to walk around unkempt. That’s actually something I debate a lot. Out of frugality and perhaps an allergy to gender roles, I’ve never learned how to put on makeup. I wear my hair in a braid because I literally don’t know what else to do with it. I’m currently sporting the first manicure of my entire life.

BELANGER: Ooh, it’s nice.

HALDEMAN: Oh, thank you. But it’s so funny. I’m approaching 40 and I finally got a manicure. I know I’m affected by it. I know when someone shows up and they have that incredible dash of eyeliner and their hair is impossibly in place, I experience a sense of awe.

BELANGER: I think we’re conditioned to associate maintenance with beauty. That’s what my experiment was. What are we valuing as beautiful? Are we valuing health and something natural? Or are we valuing consumption?

HALDEMAN: Right. Well, heroin chic isn’t quite in the way Lululemon-fit is, right?

BELANGER: Yeah.

HALDEMAN: But I guess that’s just a changing beauty standard of maintenance. Do you go somewhere for inspiration?

BELANGER: I want the information I consume to balance my life. I go to all the museums for inspiration though. I love living in New York and being able to go to the museums each week.

HALDEMAN: Do you have a favorite object in the Metropolitan Museum?

BELANGER: I never have a fixed favorite object. But did you notice that they’ve taken out a ton more ceramics? I’ve never even bothered to be like, “What are these?” Maybe I should look it up. Some really incredible ceramics were on display, little lizards.

HALDEMAN: Oh, wait. I know what you’re talking about.

BELANGER: Yes, made into these platters that are the craziest things I’ve ever seen.

HALDEMAN: They’re insane. I was looking at that like, “How does this exist? And why is it so detailed?”

BELANGER: And why were these never on display before?

HALDEMAN: Right. I need to talk to a ceramicist about these, but do you think they’re cast? The leaves and the twigs.

BELANGER: I think parts of them are made by hand and then parts are cast. It’s some incredible craftsmanship that I haven’t seen in anything contemporary.

HALDEMAN: How do they cast the snake and make it look so lifelike? I figure you have a dead snake and then it’s very limp and you try to cast it. [Laughs] I guess there are ways.

BELANGER: Dead-looking lizard. That’s cool.

HALDEMAN: There’s an object that I feel very passionate about at The Met. And if we were at The Met together, I’d be like, “Genesis, you have to see this.”

BELANGER: What object is it?

HALDEMAN: It’s a black Greek vase with this incredible neck. But around the neck is a painting of a necklace with a clasp in the back.

BELANGER: I need to see this.

HALDEMAN: And then they have a similarly styled necklace nearby.

BELANGER: The Met has been keeping something from me.

HALDEMAN: Well, I stalk around The Met looking for that one detail where the artist has lost their mind, or where they’ve spent too much time with the object and suddenly they’re putting necklaces on it.

BELANGER: Maybe we’ll have to go together.

HALDEMAN: I can pinpoint it on a map for you. Don’t get me wrong, I would absolutely love to go to The Met with you.

BELANGER: Yeah, I think we should just go together.

HALDEMAN: Sounds good.

BELANGER: We can find out where those cast little mini snakes are from, too.

HALDEMAN: I go to The Met as a painter and think about images being frozen in time. There’s a painting of a boy in the Egyptian wing with a surgical cut in his eyeball. It’s so strange. Or there’s a painting in the Italian wing of all these women with blonde fros, and that was just the style of the time, I guess. I once had an art teacher who was like, “You can look at an art object and have a conversation with that artist no matter how old they are.”

BELANGER: That’s fantastic.

HALDEMAN: But I just can’t imagine with ceramics, because you can basically go back to the beginning of the known history of man. Like this flower that’s hanging above you, if it were to shatter into pieces and someone were to later find it.

BELANGER: Yeah, or one of the hot dogs I make. It’s a very important symbol in our culture.

HALDEMAN: It is. They wouldn’t just get it. I think archeologists really think that way. They’re like, “What is this yellow swizzle? They don’t have mustard in the future.” I know that we’ve mentioned that when you’re making ceramic objects, you’re very conscious of where the clay is coming from and the quality and consistency that you work with. When you look at clay objects in The Met, do you think about what that material might have been?

BELANGER: I think because most ceramics that we see are glazed and the beauty of the clay body is hidden, I’m not that often drawn to ceramics in general. All my clay is raw or naked, so—

HALDEMAN: Naked clay.

BELANGER: It’s naked clay. But when we look at ceramics, often what we’re seeing is glass. So it’s hard for me to look at unless there’s a chip and I can see the body underneath, or there’s a culture that didn’t glaze.

HALDEMAN: Okay, so it’s actually hard to get a sense of the clay body of these objects. Really early on when I was trying to understand how my artwork would live in the world. I loved to consider cuneiform tablets, because on the back of the cuneiform tablet, there was a thumbprint. It really struck me that part of the allure of the art object is the presence of the maker. Not that you have fingerprints in your clay, I don’t know where your fingerprints go.

BELANGER: But there’s the difference between an object that’s made by a body and an object that’s the result of a mechanical process. I’m not making a value distinction, but there is a difference. There’s something unnameable in that imperfection of a handmade object, even subtly, because I think both you and I are not making very imperfect objects.

HALDEMAN: I actually do think about this fetishization of an expressive mark and how that can become performative. An expressive mark means emotion or expression. I often associate it with wildness and masculinity. And I think maybe I’m choosing to make a mark that expresses quietness and consideration. But it’s still a handmade mark.

BELANGER: I think that there’s something quick and gestural about those marks, but they’re actually perhaps somewhat labored over. And if you really have a mastery of your material, you can make a mark that looks precise and thoughtful, but maybe is actually quite gestural. I find this obsession with the expressive to be a sign of lazy looking.

HALDEMAN: Oof.

BELANGER: I know.

HALDEMAN: No, I love it. There’s a lot to question. Thank you Genesis, for starting us off on a line of thought.

BELANGER: But then we just rolled down the tangent hill.

HALDEMAN: Yeah. Well, I can’t wait to be publicly humiliated in our conversation.

BELANGER: Me too. I’m so looking forward to it.

HALDEMAN: I hope to see you soon.

BELANGER: Yeah, let’s go to The Met.

HALDEMAN: Oh, yes.